1913

Songs of Palestinian Jews from the Collection of Isaac Lurie (1913)

Recordings released by the Institute for Information Recording of the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine.

Link to the recordings in the website of Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine. Below are annotations by Edwin Seroussi and Netanel Cohen-Musai, January 2023.

The notes for each track include the original write up from the website of the Institute for Information Recording (even when it does not correspond to the recording) for the record, followed by our clarifications, corrections and additional materials in the following paragraphs. For the sake of consistency, we have rearranged the items according to musical traditions but maintained the original numbers of Volume 9 for easy reference by users of the Kyiv Collection website. When there is more than one piece in a cylinder, the pieces were described considering the timing of each one within the cylinder. This is a working paper and therefore it will be updated as more information about these recordings can be retrieved.

Tracks

Iran (Shiraz)

Iran (Shiraz)

Syria (Aleppo)

Instrumental piece

Syria (Aleppo)

Syria (Aleppo)

Syria (Aleppo)

Syria (Aleppo)

Syria (Aleppo)

Syria (Aleppo)

Morocco

Morocco

Iraq (Baghdad)

Iraq (Baghdad)

Iraq (Baghdad)

Iraq (Baghdad)

Iraq (Baghdad)

Iraq (Baghdad)

Iraq (Baghdad)

Iraq (Baghdad)

Iraq (Baghdad)

Iraq (Baghdad)

Iraq (Baghdad)

Annotations by Edwin Seroussi and Netanel Cohen-Musai

The collection of historical Jewish field recordings at the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine includes sixty-seven phono-cylinders with biblical cantillation, prayers and piyyutim (songs of religious content) for Sabbaths, Holydays and life cycle events recorded in 1913 in Ottoman Palestine from Jewish singers belonging to Middle Eastern communities living in Jerusalem. Isaac Lurie (1875-1930), curator of the Museum of the Jewish Historical and Ethnographic Society in Saint Petersburg, carried out these recordings. At the present, the Institute for Information Recording at the Vernadsky Library has released thirty-nine tracks, as Volume 9 of its collection of Jewish materials.

This section of the Ukrainian sound archive in Kyiv has attracted less attention in comparison with the bulk of the impressive collection that consists of Eastern European Jewish materials. Yet, these recordings are among the earliest surviving specimens of Middle Eastern Jewish musical traditions. By nature of the technological circumstances in which they were recorded, these sonic fragments offer very limited information for any scholar or performer interested in them. Yet, if properly contextualized, these scattered and unsystematic archeological sound remains offer the modern listener a partial glimpse into the soundscape of Jewish Jerusalem in 1913.

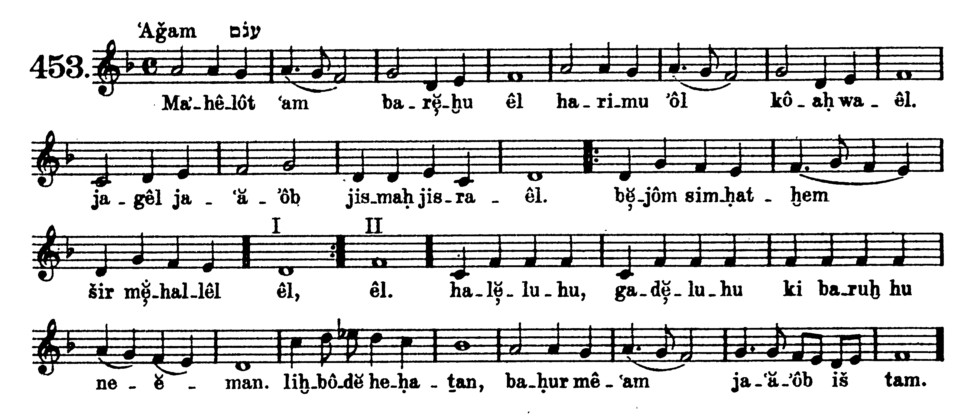

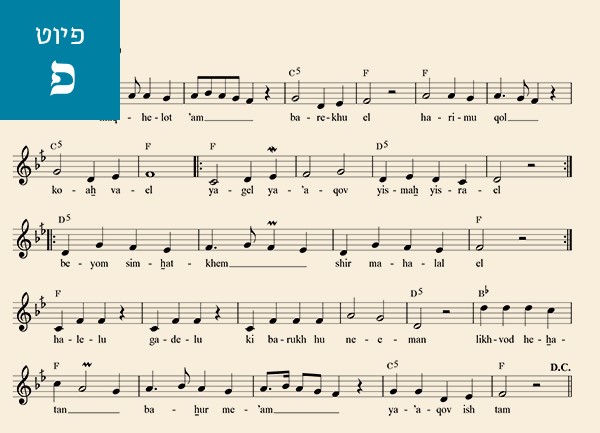

Moreover, for the scholar, these recordings are an unprecedented opportunity to validate historical theories of musical change that have been based solely on the much-appreciated recordings and transcriptions made by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn that were carried out approximately at the same time and place as those of Lurie. For example, the transcription made by Idelsohn to the popular wedding song "Maq’helot ‘am", a poem by Mordecai Abadi of Aleppo (1826-1884) (Idelsohn HOM, IV, no. 453; see example 1) reflects a version different than the one that eventually became popular in the contemporary practice of the descendants of Aleppo Jews in Jerusalem (see example 2).

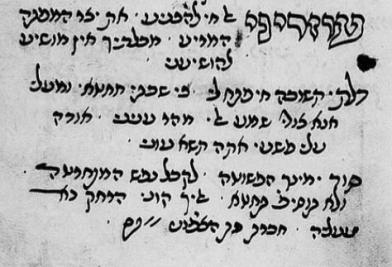

Example 1: "Maq’helot ‘am" transcribed by A.Z. Idelsohn (Idelsohn HOM, IV, no. 453)

Example 2: "Maq’helot ‘am". Source: Piyut Website.

Idelsohn’s version seems slower in tempo and perhaps closer to the original Turkish melody to which Abadi's text was set in comparison to the current practice. However, it was difficult to draw decisive conclusions about the transmission of this melody based only on Idelsohn’s transcription. Lurie's recording [no. 6] corroborates now the accuracy of Idelsohn's version and brings to life the changes that occurred in the process of transmission.

The online publication by the Institute for Information Recording in Kyiv offers the primary metadata of these recordings based on the catalogue prepared by Moyshe Beregovski. According to this publication, Beregovski based this information on the original notes by Lurie that are now lost. Very similar information is included in Lyudmila V. Sholokhova's exhaustive catalogue of the Kyiv cylinder collection, Phonoarchive of Jewish Musical Heritage: The Collection of Jewish Folklore: Phonograf Recordings from the Institute of Manuscripts. Annotated Catalogue of phonocylimders, musical and textual decodings (Kyiv, 2001) as well as the Preliminary Catalogue of the Jewish Music Collections in the Vernadsky National Library of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences in Kiev: Series A. Prepared by the staff of the Jewish Music Research Centre under the direction of Israel Adler (Jerusalem, 2010; available in our website).

Our following description on the other hand is a preliminary study of this selection of recordings based on data extracted from the recorded fragments themselves. It offers a corrective to inaccuracies in the current catalogue and fills in substantial additional information missing in the catalogue. By comparing the information conveyed by the fractured voices emerging from the cylinders with that of related contemporary sources of similar pieces one is able to recover, as in an archeological excavation, a richer understanding of these fragments.

Lurie’s recordings reflect musical practices of Jews from the Ottoman provinces of Greater Syria (Aleppo and Urfa) and Iraq (Baghdad), as well as from Iran (Shiraz), Yemen and Morocco who settled in Palestine starting in the second half of the nineteenth century. A single recording labeled “Ethiopia” poses interesting questions. The recordings are all of male voices singing solo or in groups without instrumental accompaniment. One puzzling instrumental melody by a solo flutist is the only exception.

Most interesting, the present selection does not include recordings from the communities that comprised the Jewish majority of Jerusalem, namely the Judeo-Spanish-speaking Sephardim and Eastern European Jews who by 1913 were certainly a significant presence in the city. It appears therefore that Lurie was after more “exotic” (from his perspective) specimens of Jewish musical traditions considered to have preserved traces of ancient Jewish practices. Thus, the bulk of the present selection (80.5 %) are items by Jews from Baghdad (11), Shiraz (9) and Yemen (9), all three communities perceived by scholars such as Idelsohn and Lurie as “ancient.” The rest of the recordings are from Aleppo (5) and Morocco (5). Similar proportions characterize the the content of the still unreleased cylinders.

Isaac Luria and his field work in Ottoman Palestine

Isaac Lurie was born in Novgorod in 1875. He was the archivist of the Jewish Historical Ethnographic Society and An-sky’s closest colleague in organizing the Society’s museum. In 1921 he led a Jewish ethnographic expedition in Turkestan. From 1922 on he moved to Central Asia. He was the director of the Jewish Library-Reading-Room in Samarkand and circa 1924, he became director of the Local Jewish Museum in Samarkand, that was closed by the Soviet authorities in 1931). Lurie himself died around that time, perhaps in Samarkand, probably purged by the Soviet regime. (See Viniamin Lukin, “An Academy Where Folklore Will Be” in Safran, Gabriella, Steven J. Zipperstein, and S An-Ski. The Worlds of S. An-Sky: A Russian Jewish Intellectual at the Turn of the Century. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2006, pp.281-305, quote in n. 82).

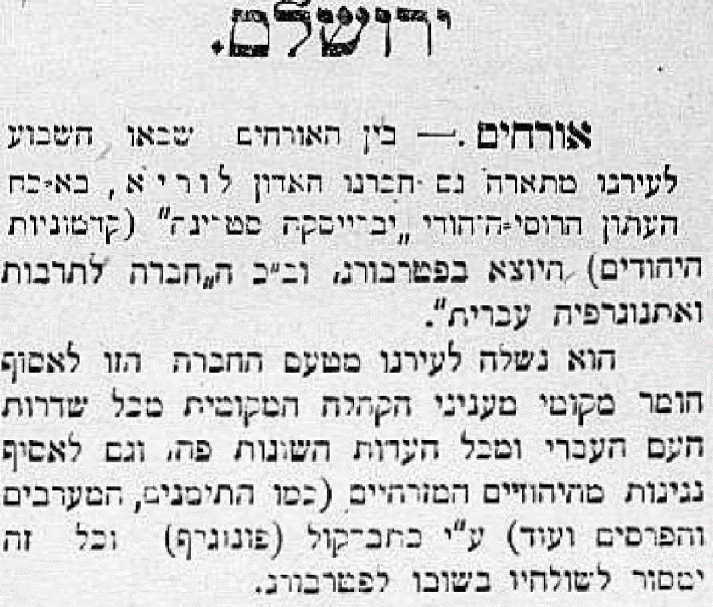

Lurie recorded in Jerusalem between July 10 and August 1, 1913. His sojourn to the city is succinctly documented in an announcement in the Hebrew daily Aherouth (i.e. Ha-herut):

Jerusalem, Guests – Among the guests who arrived this week to our city we also count our colleague Mr. Lurie, agent of the Russian-Jewish daily Evreiskaia Starina (Jewish Antiquity) that appears in Petersburg and agent of the Society for Jewish [original says “Hebrew”] Culture and Ethnography. He was sent to our city on behalf of this society to collect local materials from the lore of the local community from all ranks of the Hebrew people and from all the different ethnic groups [“’edot”] here, and also to collect melodies [“neginot”] from the Oriental Jews (such as Yemenites, Maghrebis, and Persians, and more) with the “ktav-qol” (phonograph) [literally “voice writer”] and all these [materials] he will pass on to his senders upon his return to Petersburg. (Aherout, 25.7.1913, p. 3)

Some of Lurie’s days in Jerusalem were labor intensive (July 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22), while in other days he recorded none. For the moment we have no information as to who exactly were the individuals he recorded, besides their name (usually without surnames), ethnic belonging and city of origin. Some informants were very prolific such as Ezra ben Hakham David from Baghdad (11 pieces recorded on Monday, July 21 of which seven appear in the present release). Binyamin Hafrosi from Shiraz (3 pieces) was the first to be recorded on Thursday, July 10. The recording of Tuesday, July 15 with a hazzan from Aleppo (probably the one named Halevy that he recorded on July 16) is unique because of the participation of the congregation (see below recording no. 6).

Lurie recorded at times more than one performer in the same session. On Wednesday July 16 he recorded the hazzan from Aleppo called Halevy (6 pieces of which five are released here) and Shlomo ben Aga from Shiraz (8 pieces; only three are released here). One informant, Yosef ben David Shalom represented the Moroccan (“Ma’aravi” or “Mughrabi” in the terminology of that time) community in the July 18 session dedicated to this tradition (6 tracks; four are released here). On the Saturday (probably in the evening), July 19 session he recorded a group of unnamed Yemenite Jews and Chaim ben Shlomo of Baghdad (4 pieces) and on Tuesday July, 22, Ezra ben Hakham David and Hakham Nissim from Urfa. On July 27 he only met with Shlomo ben Yitshak from Ethiopia to record two pieces (only one is released here). Two Yemenite singers Abraham ben Zekharya and Shimon ben Shalom Meir, were recorded at the very end of the journey on July 31 together with Zekharya ben Ovadia and Ben Zion ben Moshe, both of San'a, whose recordings were not released in the present publication. On the last day of recordings (August 1, 1913) Lurie encountered the only "non-Oriental" Jew, Yaacov, a carpenter (plotnik) from the "colony of Petah Tikvah", sang for him Haim Nachman Bialik's famous Hebrew song "Beyin na'ar Prat la-Hideqel". This may be one of the earliest recordings of Shirei Eretz Yisrael (Songs of the Land of Israel).

Lurie’s informants differ, as far as we can ascertain, from those recorded by Idelsohn in 1911-1913, his most prolific recording years. It is puzzling that no mention of an encounter between these two men ever occurred. Having two Eastern European Jewish ethnographers recording with phonographs in such a relatively small community as Jerusalem in 1913 is more than a coincidence. It is also debatable if in the summer of 1913 Russian Jewish ethnographers in Saint Petersburg were fully aware of the scope of Idelsohn’s work in Jerusalem. Moreover, Idelsohn may have already embarked on a trip to Vienna when Lurie arrived to Jerusalem. Alas, for the moment we must leave the question of a possible contact between these two men open.