Lehakat Tzlilei Ha’ud

The Modernity of Piyyut Creativity: Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni'a

Introduction: The Issue of Authorship

‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’, a most beloved pizmon from the contemporary Sephardi repertoire, has a very peculiar history, one that illustrates the social mechanisms involved in the creation, transmission and performance of sacred Hebrew poetry in the modern period. This song is universally attributed to Rabbi Refael Itzhak Antebi of Aleppo (b. Aleppo, 1830 – d. Cairo, November 7, 1918), also known as Tabush, one of the most prolific authors and disseminators of Hebrew sacred poetry in the Levant of the late nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

The only reservation to this attribution derives from the acrostic of the poem: “Ades.” Rabbi Antebi used only the acrostic of his name “Refael” or, when he dedicated a poem to some personality from Aleppo or a family member, he used as acrostic the name of the individual being honored. However, the website www.pizmonim.com, claims that Rabbi Antebi belonged to the Ades family, while the surname Antebi simply refers to the origin of his family in the city of Aintab (today Gaziantep in southwest Turkey, close to the frontier with Syria). Yet, significantly, he did not use the acrostic “Ades” in almost any of his hundreds of poems. On the other hand, the Ades family was an important rabbinical family from Aleppo and a contemporary of Rabbi Antebi, Rabbi Avraham Haim Ades (1848–1925), who moved from Aleppo to Jerusalem in 1896, may have well been the addressee of our song, even though none of the sources available at this moment testify for such a dedication.

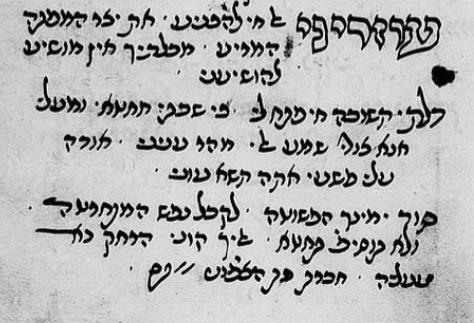

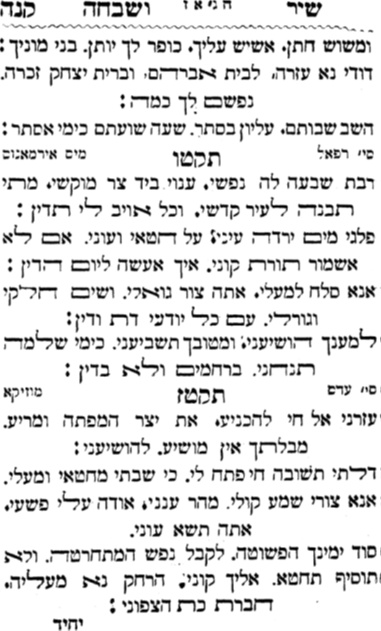

‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ appears for the first time in print in Qol Zimrah, a collection of piyyutim edited by Hebron-born educator, publisher and poet Rabbi Yehuda Castel (1871-1936). The book was published in Jerusalem in 1896 and reprinted, due to high demand according to the introduction by the author, in 1901. It included mainly the poetry by Rabbi Antebi, whose name is specifically mentioned in the title page (“Songs and praises…that composed…Refael Itzhak Antebi… and some by me…”). Antebi probably met Castel upon arriving to Jerusalem for the investiture of Rabbi Yaacov Shaul Eliyashar as Rishon le-Tziyon, chief Sephardic Rabbi of the Land of Israel that took place at the “Great Synagogue” (Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakai) of Jerusalem’s Old City on February 1, 1893. Antebi, composed a special poem for the occasion, trained a choir for its performance and was handsomely rewarded by the new Chief Rabbi. He eventually settled in Jerusalem before moving to Cairo towards the very end of his life, where he died. Antebi’s songs were also published in other Jerusalemite publications appearing soon after, such as Shir u-Shvahah edited by Rafael Haim Hacohen (1905; reprinted in New York in 1919 on behalf of the large community of Jewish immigrants from Aleppo) and Shirei Nai’m edited by Ben Zion Gul Shauloff, a collection of piyyutim with Persian sharh (explanatory translation) published on behalf of the large Persian-speaking communities of Jerusalem’s new city (1913).

This impressive string of publications in Jerusalem is a testimony to the reception of Rabbi Antebi’s poetry in the city and its foundational role in the local singing of bakkashot in the early mornings of the Sabbath among immigrants from Aleppo in particular and from all the Eastern Jewish centers (such as Iran and Central Asia) in general. Moreover, in Jerusalem Antebi composed a few pizmonim based on melodies from the Judeo-Spanish repertoire, catering probably to the Ladino-speaking majority of the Sephardic community in the city.

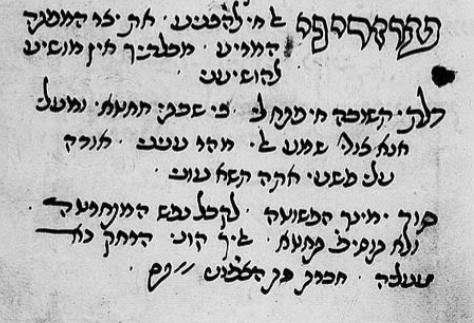

Figure 1: ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ in Shir u-Shvahah (1905), p. 155.

We are able now to date more precisely the composition of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ and tracing its diffusion. First, it needs to be pointed out that the song was not included in the book of songs that Rabbi Antebi published while still in Aleppo in 1888, Sefer Shirah Hadashah. This book is unique in that in opens with an extensive sermon by the author in which he fulminates against his coreligionists who are attracted to popular Arabic songs. Paradoxically, in all his works Rabbi Antebi shows his remarkable proficiency in the very same repertoire (including classic muwashahat from Aleppo) that he rants about because the vast majority of his poems are set to the melody of an extant (and probably popular at the time) Arabic song.

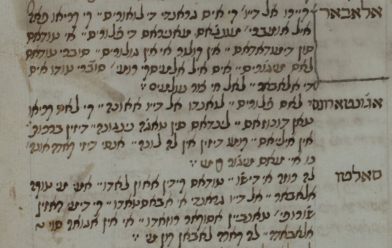

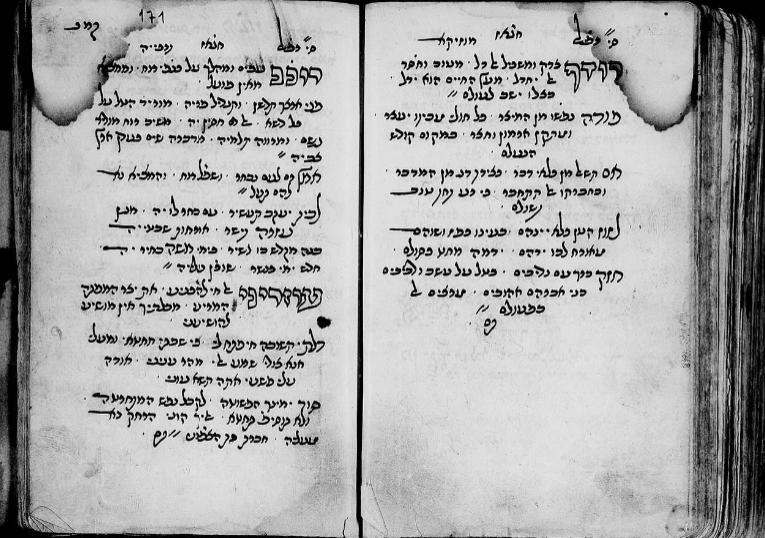

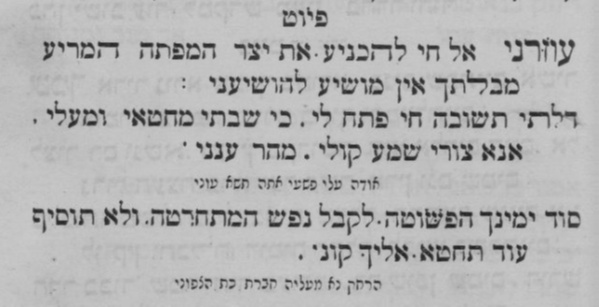

In addition to the printed sources, few manuscripts containing substantial portions of the poet’s output have survived. All these sources are the work of scribes who were closely associated to the Rabbi and documented his songs as their author was blind and thus unable to write them down himself. One such manuscript, and a remarkable one, is Ms. 80 3187 of the National Library of Israel. This is a copy of the printed book Sefer Shirah Hadashah pasted together with a large manuscript two-hundred sixteen pages long that contains mostly songs by Antebi as well as by other contemporary poets. Both the printed book and the manuscript are arranged according to the Turkish makamlar or Arabic maqamat, as became customary in the Levant since the days of Rabbi Israel Najara in the late sixteenth century. ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ appears in fol. 171a of this manuscript in the section corresponding to maqam Hijaz.

Figure 2: ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ in NLI, Ms. 8o 3187.

It makes sense to argue that the songs in this manuscript were mostly composed or compiled after 1888, the date of publication of Sefer Shirah Hadashah. For the moment, this is the only manuscript that contains the song, as other important collections of Rabbi Antebi’s poetry, such as British Library Or. 10375 and National Library of Israel, 8o 6368, do not include it.

Thus ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ was probably penned sometime between 1888 and 1896, the date of its first printing in Qol Zimrah. Moreover, it is probable that the song was composed after Antebi settled in Jerusalem and that the compound source, half printed and half manuscript, belonged to Antebi himself or to one of his associates.

The Original Version

Two facts are remarkable in the earliest versions of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’. In the National Library manuscript there is no reference in the title to any Arabic song. In the printed version of the poem Qol Zimrah, always under maqam Hijaz, the title is “Muziqa” which in this context means “an instrumental melody” or as musicologist A.Z. Idelsohn remarked “a piece for the military orchestra” (HOM, vol. 4, p. 99; Idelsohn had in mind the orchestra of the Ottoman Army stationed in Jerusalem). As we shall see, the contemporary melody of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ is a well-known Arabic song. If this melody was known to Rabbi Antebi and he intended it for his song, it makes sense that he would have quoted it in manuscript or in the printed edition of his song.

The second issue related to ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ is that the attribution of the song to the Yamim Nora’im (The Ten Days of Repentance) does not appear in any of the early sources of the text. Most probably the content of the song, a very personal plea by the poet to resist evil forces (‘Help me, living God, to subdue the evil spirit of temptation’ is the opening) and be granted forgiveness from sins by the Almighty (‘For I have turned from my sins and from my transgressions, I am a sinner, hear my voice, answer me speedily’), led later editors of piyyut collections to classify the song as belonging to the Days of Repentance. Such classification appears for example in Shir u-Shvahah/Hallel ve-Zimrah (Jerusalem, 1964), a compendium combining Rabbi Antebi’s poetry with that of Moshe Ashear (1877-1940), his direct disciple and protégé, that became the main codex for the singing of bakkashot and pizmonim for all occasions among Aleppo Jews in all their diasporas.

The melody of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’

The melody to which ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ is sung today is ‘Ya Farid al-Husni Ashek Jamalek’ (يا فريد الحسن عاشق جمالك; Oh, unique beauty, lover of your beauty). This Arabic song was recorded by the renowned Egyptian diva and actress Sitt (Mrs. or Lady) Munira al-Mahdiyya (مونيرة المهدية, 1885-1965). According to Alan Kelly’s Catalogue, the recording of the song (titled in the record ‘Ya Farid el hossne’) released by Zonophone (CatNum: 10407, matrix no. X-103417), was made in Cairo in May of 1907 when Munira was still a young rising star. A later recording by Munira for the Baidaphon label (at 06:45) shows a more adult and developed voice. This recording is of much better quality also in terms of the instrumental accompaniment. The melody in both recordings of this rather simple song consists of three sections: one for the stanza, one for the refrain (reaching the highest pitch of the maqam), and a short ending section, an exit (khruj) in lively 6/8 meter.

Munira al-Mahdiyya became Egypts’s most remarkable female voice in the first decades of the twentieth century, appearing live through the Middle East. Her recording of ‘Ya Farid al-Husni’, especially the Baidaphon one, could have easily been heard through gramophones installed in cafes in Jerusalem or Cairo. However, the question since when was ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ set to this Arab melody and by whom, Rabbi Antebi himself or someone else, remains unanswered. Significantly, the song does not appear in A.Z. Idelsohn’s publications, especially vol. 4 of HOM that includes a sizeable collection of Aleppo pizmonim in musical transcription. Idelsohn’s main research in Jerusalem was carried out between c. 1907-1914, and perhaps at this time ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ was not as popular as it is today.

Early Sonic Documentation of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’

The earliest sonic documentation of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ is found in a recording made by the eminent German comparative musicologist Robert Lachmann in Jerusalem on November 11, 1936, in the framework of his documentation of “Oriental” Jewish traditions. This is one of several recordings by young members of the Elnadav family, Joseph, Netanel and Refael. This Yemenite family from Jerusalem was considered a particularly musical one and for this reason Lachmann selected them for his field documentation. The fact that the Elnadav singers selected ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ for their recording shows that by 1936 the song had acquired popularity, at least in circles of synagogue singers in Jerusalem, many of whom were personally acquainted with Rabbi Antebi. Moreover, in a personal interview with me, Rabbi Refael Elnadav (1920-2012), who as an adult became a towering figure in the world of Sephardic hazzanut (and in his late years, cantor of the Syrian community in Brooklyn), conferred that as a child he knew Yehuda Castel, the editor of Qol Zimra and learned from him. Was Castel then one of the agents who spread ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ among a wider audience?

Be that as it may, in the Elnadav family recording the melody of ‘Ya Farid al-Husni Ashek Jamalek’ as sung by Munira is very clear, including its last fast section, not in 6/8 but in 2/4. Another interesting detail is the addition of the interjections “Eli, eli” in between the repetition of the first phrase, a small and yet significant detail when tracing the later reception of the song in Israel (see below). This last music section of Munira’s recording (the khruj) covers the additional long line found between stanzas 2 and 3, and is repeated (unlike the Arab original) with the long line ending the poem. These two long lines digress from the clear structure of the poem, three four-line stanzas rhyming aaax, bbbx, cccx, and they probably derive from the structure of the original music to which the poet intended his poem to be sung.

עָזְרֵנִי אֵל חַי לְהַכְנִיעַ

אֶת יֵצֶר הַמְפַתֶּה הַמֵּרִיעַ

מִבִּלְתְּךָ אֵין מוֹשִיעַ

לְהוֹשִׁיעֵנִי

דַּלְתֵי תְשׁוּבָה חַי פְּתַח לִי

כִּי שַׁבְתִּי מֵחֶטְאִי וּמַעֲלִי

אָנָּא צוּרִי שְׁמַע קוֹלִי

מַהֵר עֲנֵנִי

אוֹדֶה עֲלֵי פְשָׁעַי אַתָּה תִשָּׂא עֲוֹנִי

סוֹד יְמִינְךָ הַפְּשׁוּטָה

לְקַבֵּל אֶת נֶפֶשׁ הַמִּתְחָרְטָה

וְלֹא תוֹסִיף תֶּחֱטָא

אֵלֶיךָ קוֹנִי

הַרְחֶק נָא מֵעָלֶיהָ חֶבְרַת כַּת הַצְּפוֹנִי

The Elnadav recording echoes in another early version, this one by the cantor, composer and educator Nissan Cohen Melamed (1906-1983). It was recorded on October 11, 1953 by Kol Israel (Israeli Radio) for broadcasting purposes. Cohen Melamed is accompanied on the piano by Max Lampel, a prominent figure in the Western European musical scene of British Mandate Palestine and during the early days of Israel. Singing with a heavy nasal voice, Cohen Melamed attempts to preserve the “Oriental” flavor of melody, though the maqam Hijaz is somehow “flattened” by him while the “um-pah” chords of the piano accompaniment are not always well aligned with the melodic line. In spite of its peculiar characteristics, this abridged version of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ (only the first two stanzas and the one long line at the end) certainly belongs to the line of transmission shown in the Elnadav family recording, including the “Eli, eli” interjection in between the repetition of the first musical phrase.

Late Reception

In spite of the gravity of the text and its categorization as a song for the Days of Repentance (at least among Aleppo Jews), ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ eventually became a popular song for semahot, joyful events and also for the Sabbath table. This dissonance between the content of the text and its performance in happy occasions is attributed to its catchy melody. Some justify this dissonance by claiming that the song actually celebrates the rejoicing caused by the individual overcoming temptations and being absolved for any sins. In any case, the page of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ in the authoritative Aleppo pizmonim website still reads: “The melody of this pizmon is taken from the Arabic ‘Ya Fareed El Hosn Ashaq Gamalak,' and it can be transposed to Shav’at ‘aniyim [from the morning liturgy] exactly one day a year, on Yom Kippur [Day of Atonement] alone.”

Sung by the great Aleppo hazzan Gabriel Shrem followed by the same tune applied to Qaddish. Courtesy of www.pizmonim.com

The reception of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ as a popular song of rejoicing, however, has more tantalizing turns as nowadays it is sometimes considered as a Moroccan piyyut. Why and how did this song from the Levant become identified in the past few decades as “Moroccan”? And how did it turn into an extremely popular Israeli “Oriental” hit? Moreover, in a most unexpected turn of events, ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ also became a Hasidic nign in the Chabad court in Brooklyn. These unanticipated paths of reception of the song are indicative of a liquid modernity, a social ecosystem in which the transmission of cultural assets is fortuitous and non-linear.

The Moroccan Story

In his book Meknes, Yerushalayim deMoroko (Jerusalem: The Author, 1995 included in the website Rayonnement du Judaïsme Marocain), Itzhak Toledano relates that Rabbi Shalom Messas (1909-2003), one of the most distinguished rabbinical authorities of Meknes in the twentieth century (and later on of all Moroccan Jews and Israel), used to sing ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ during the opening of the Torah Ark on Rosh Hodesh (New Moon). He was “fond of this song” that is included in the compendium of bakkashot according to the Meknes tradition, Yismah Israel (Meknes, 1931, p. 249).

The inclusion of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ in a Moroccan printed collection as early as 1931 is testament to the rapid dissemination of piyyutim along the Mediterranean basin. Transmission of songs do not entail large movements. Enough that a single person travels from one end of the Sea to another with a song collection in his baggage to activate a chain of transmission. Indeed, pizmonim from Aleppo were already published in large numbers in Algeria, in the book Shirei Zimrah (published by Eliyahu Guedj, Algier, 1889). Hebrew sacred songs from the Levant reached the Maghreb even in earlier periods through shadarim, fundraisers from the Holy Land who visited the Western confines of the Mediterranean (and vice versa, as shown by the presence of Rabbi David ben Hassin’s songs in Oriental sources since the early nineteenth century). Moreover, even an object, such as a printed book of piyyutim, can be moved by an occasional agent and made accessible far away from its place of publication.

We do not know how ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ was sung in Meknes. Yet, the persistence of the melody of ‘Ya Farid al-Husni Ashek Jamalek’ among Moroccan singers in later periods may indicate that not only the text was transmitted across the Sea, but also its “original” melody.

Figure 2: ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ in Yismah Israel (Meknes, 1931)

The acquired “Moroccaness” of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ is also related to its transmission to Chabad, the next evolution in the song’s history.

The Chabad Story

In 1953, Rabbi Nissan Pinson, the first emissary of Chabad to Morocco visited the court of Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson in Brooklyn for the first time since his appointment. According to Chabad sources, Rabbi Shimon Ohayion (probably the head of the Keter Torah Yeshivah in Casablanca, 1906-1990) asked Pinson to transmit ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ to the Rebbe who, upon hearing it, immediately adopted it and even occasionally performed it himself (recorded April 12, 1957). The Rebbe sings it slowly and with fluid beat, rendering it as a meditative niggun unlike all other performances. Other sources simply maintain that Rabbi Pinson sang this pizmon when the Rebbe asked him to sing a Sephardic niggun. The names of two other prominent Sephardic emissaries of Chabad are also mentioned as either transmitters of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ or as those who performed it at the Rebbe’s court, Rabbi Yehoshua Hadad (Milano) and Rabbi Aharon Tawil (Buenos Aires; you can hear a first-hand account of the events from Rabbi Tawil’s son including a recording of it).

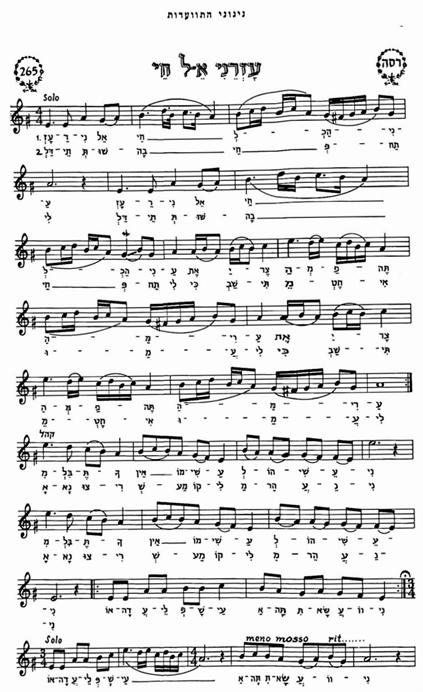

Since then, in any case, ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ has been considered as a Chabad niggun, performed in the public assemblies with the Rebbe (fabrengen). It became an emblematic sonic expression of the openness of Chabad as a movement and of the Rebbe as a leader towards the Sephardic and Oriental Jews. The third volume of the Sefer HaNiggunim (1980) includes the song, as ordered by the Rebbe to its editor, Rabbi Shmuel Zalmanov (niggun no. 265).

Figure 3a: ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ from Sefer HaNiggunim of Chabad, vol. 3.

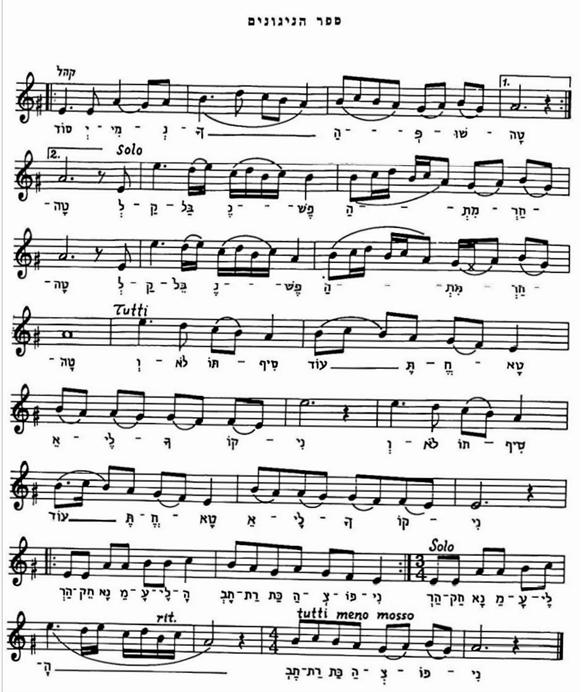

The transcription shows that the niggun is intended for a responsorial performance between a soloist and the congregation (tutti), whereas the solo sections present melodic variants that are unique to the Chabad version. Zalmanov himself can be heard singing the niggun, with text, in a recording of the National Library of Israel (sung “to the Moroccan melody” according to the catalogue). The pizmon also appeared on the 11th album of the Niggunei Chabad series published by the official Chabad record label Nichoach in 2000. Interestingly, this version is much closer to contemporary Israeli “Oriental” versions (see below) rather than to the niggun-oriented text-less versions sung in Chabad gatherings.

Figure 3b: ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ from Sefer HaNiggunim of Chabad, vol. 3. Modern transcription with transposition to G, courtesy of https://nigunimbimbom.org/search/?query=chabad+265

Over the years, ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ has also been performed by popular Hasidic singers such as Avraham Fried. A unique cover version of the pizmon by Idan Rafael Haviv is included in the album Tzam’ah 4, an installment of a project dedicated to renewed contemporary performances of niggunei Chabad. Finally, Chabad has produced a remarkable educational kit for children about this niggun, including the history of its inception by the Rebbe, an explanation of the content of the text, a “soft” instrumental arrangement and clips of the arguably first performance by Rabbi Pinson and the recording of the Rebbe singing it. The video stresses the unbound message of Chabad that also reaches the “Orient,” a geographical spread that explains how a Sephardic pizmon can become a Hasidic nign.

Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach had a fond memory of this nign, probably from his days at the Rebbe’s court. Here is a rare recording of his reminiscence:

‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ as “Zemer ‘ivri” and Mizrahi pop icon

The reception of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ as integral to the universal canon of Sephardic pizmonim can be seen in its numerous iterations in recordings, online sites and even in its inclusion in the Sephardic Siddur by Artscroll, an authoritative modern version of the Jewish prayer book. The rapid spread of the song and its innumerable commercial recordings in Israel also led to its inclusion as an “Israeli” song in the Zemereshet website that includes links to a wide selection of popular versions.

From the Israeli commercial recordings of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ that set the tone for its universal reception as a Mizrahi or “Mediterranean” song two should be mentioned: the early one by Lehakat Tzlilei Ha’ud (1975) and the later by Daklon (Yossef Levy; 1996).

These arrangements present not only musical innovations in terms of the overall “Mediterranean” sound (the improvised qanun introduction, the bouzouki riffs, the deep electric bass guitar in the Tzlilei Ha’ud recording) and in the delivery of the melody (such as Daklon’s melismatic extension of the opening phrase) but also alterations of Rabbi Antebi’s text (in the third stanza, ‘yad yeminkha’, “your right hand”, instead of the kabbalistic concept of ‘sod yeminkha’ “the secret of Your Right”; ‘lo tossif lehet’i’, “you will not add to my sin” instead of ‘lo tossif teheta’, “you will not sin anymore”). Such alterations probably derive from the oral transmission of the song. In addition, these recordings show a link to the earliest documentation of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’ by the Elnadav family, in their addition of an interjection between the repetitions of the first phrase. However, the “Eli, eli” of the Elnadavs is transformed into “hevi’eni,” probably a “lick” from the song “Hevi'eni el beit ha-yayin” made famous by the same artists around the same time they recorded ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’. This quotation probably derives from the shared maqam, especially the almost identical ending cadences of both songs.

A comparable example of melodic adaptation is found in another Jerusalemite piyyut, documented in a context similar to that of ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’. This piyyut, Yah el magen ve’ozer, was set to the Ladino melody Cinco años ya va hacer. Like ‘Ozreni El Hay Lehakhni’a’, it is included in Yehuda Castel’s Sefer Kol Zimrah and was recorded in 1937 by Robert Lachmann, as performed by members of the Elnadav family. (For a detailed discussion, see here.)