Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Articles

The Hebrew Version of Abû l-Salt’s Treatise on Music

Modern research has failed to add substantially to our knowledge of the Arab author Abu l-Salt (1067-1134) or of his works, which include a treatise on the science of music. The information available continues to be based mainly on the records of the old Arab biographers and bibliographers. Thus H.G. Farmer only repeats the contemporary evidence on Abu l-Salt's extraordinary gift for instrumental performance and composition, and his theoretical writings on music. An extensive musical treatise of his has come down to us in a Hebrew translation, but not in the original, and its contents and character have remained practically unnoticed by modern research. The present writer has already had the privilege of supplying firsthand information based upon an examination of that text. In accordance with the Talmudic saying 'If you have started performing a task - then complete it,' and in response to an invitation by the editors of Yuval, the full text of this unique manuscript will be given here together with a translation and critical notes.

Articles

Jubal in the Middle Ages

Mediaeval treatises on music usually begin with a series of stereotype questions and answers, very often in the following order: (1) Quid sit musica; (2) unde dicetur; (3) a quibus sit inventa. The answers amount to a more or less comprehensive inventory of the various definitions of music, its subdivisions, its effects, its etymology, and its inventors.

Two figures have claimed the right of being the first inventors of music. Pythagoras, the first to have defined sound and sound relations in numerical proportions, represents the classical view on the beginnings of musical science. Jubal, 'the father of them that play upon the harp and the organ,' steps out of ancient, antediluvial times in Genesis IV together with his brother Jabel ('father of such as dwell in tents and of herdsmen'), his half-brother Tubalcain ('a hammerer and artificer in every work of brass and iron') and a half-sister Noema, of whom the Bible, at least, says nothing.

Articles

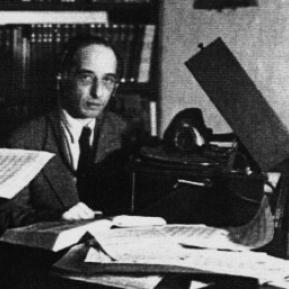

Robert Lachmann: His Achievement and His Legacy

Two memorable anniversaries in the history of Ethnomusicology occurred in 1972: the ninetieth return of the birth of Abraham Zwi Idelsohn (14.7.1882-14.8.1938), and the eightieth of Robert Lachmann (28.11.1892-8.5.1939). Though by different ways and means, both scholars became the founders of Comparative Musicology in Israel for both the Jewish and the Arab cultures. The following lines are dedicated to the scientific contribution of the younger of the two, Robert Lachmann.

Articles

The Hasidic Dance-Niggûn - A Study Collection and its Classificatory Analysis

In our article on Hasidic music we described the problem of the definition of the Hasidic niggûn (melody of the Hasidic patrimony proper) as follows:

'By one definition, the field of hasidic music would include all music practiced in hasidic society. By another, and related, definition any music performed in 'hasidic style' is hasidic. A further possibility would be to define hasidic music by its content, i.e. by those musical elements and forms which distinguish this from any other music. So far, such distinctions have not been formulated according to the norms of musical scholarship. The Hasidim themselves also possess criteria formulated in their own traditional terms - according to which they judge whether a melody is 'hasidic' or not, and to which dynasty style and genre it belongs. These, too, have not yet been translated into ethnomusicological terms. Moreover, none of the extant studies of hasidic music have as yet managed to furnish a systematic description of the hasidic repertoire or even part of it.' The present study is a first step towards the remedy of this lack.

Articles

“‘Ên Kol"- Commentaire hébraïque de Šem Tov ibn Šaprût sur le Canon d’Avicenne

L'objet principal de cette étude est la traduction annotée d'un passage relative à la nature musicale du pouls tiré du commentaire hébraïque de Sem Tov ben Isaac ben Saprût sur le célèbre ouvrage d'Avicenne Le Canon de la médecine (Al-Qanun fi l-tibb). Le Sayh abu 'Ali ibn Sina 'prince des philosophes', d'après ses contemporains, est né en 930 à Atfana près de Buefara et déja à l'age de 18 ans on le trouve en tant que medecin au service du Sultan Nuh ibn Mansur de Buhara. Avicenne excella dans toutes les branches du savoir de son temps, mais parmi les cents ceuvres qu'il a écrites, deux en particulier l'ont rehdu célèbre à travers l'orient et l'occident; ce sont: le traité philosophique al-Sifa' et le monumental Canon de la médecine. Le Canon a été, grâce aux traductions hébraïques et latines, la Bible des médecins jusqu'au XVIIe siècle; ainsi la traduction latine ift l'objet de sept éditions en Italie entre les années 1507 à 1595. Quant aux traductions hébraïques on en connait actuellement trois et une trentaine de commentaires (nous connaissons les auteurs de treize d'entre eux et dixsept sont anonymes).

Articles

The Reliability of Oral Transmission: The Case of Samaritan Music

In the absence of theoretical formulation concerning the processes of oral transmission of musical culture, the selection of informants in ethnomusicological research is necessarily haphazard. Yet, without a clear idea of who your informants are it is difficult to elaborate adequate theories. In Vansina's words, 'the value of oral traditions as historical evidence is a problem that has not been solved, because the special nature of oral traditions as a source of information about the past has not been provided.' Of course, no single theory can be expected to apply to all societies, since the 'chain of testimonies' is a function of the network of social communication, and this appears -at least so far- to vary from culture to culture. Thus the starting point for the study of an oral musical tradition must be an examination of the potential network of cultural transmission within a particular society.

Articles

Melody and Poetry in the “Kuzari” (Hebrew)

Paragraph II, 70 of Judah Halevi's Kuzari speaks of the relationship between melody and textual metre in two kinds of vocal music. The precise meaning of this passage has long been contended, since each of the salient terms allows for several interpretations; some of them also have disputed manuscript readings. Nor does Judah Ibn Tibbon's mediaeval Hebrew translation of the Arabic original resolve the difficulties. The context is a comparison of the Hebrew and Arabic languages. After discussing the uses of the various terms in other Arabic and Jewish-Arabic sources, the following interpretation is proposed:

'Said the savant: it has already been established that cantillation melodies are independent of the metrical symmetry of the text. One may sing to the same melody 'Give thanks to the Lord for He is good' and 'To Him Who alone doeth great wonders' (Ps. 136, v. 1 and 3, seven as against twelve syllables), by 'empty' and 'full' tones. This is valid for the melodies-of-action (Biblical cantillation which is uttered with movements, or for practical resp. useful purposes). For the metrical poems, however, which are verbose and declamatory, and are performed for entertainment, the adherence (of the tune) to the textual metre is appropriate. This is because their status is low in comparison with that of the melodies-of-action, which is the highest and the most useful.'

Articles

The Influence of Choral Elements on the Formation and Development of the Piyyût Genres (Hebrew)

In the Talmudic period the vocal participation of the congregation in the prayers was minimal. It is excluded by the early Palestinian piyyûtim, which are in continuous-flow forms. Subsequently there appear, in certain genres of the piyyût, sections which contrast with the main body in both structure and metre. The only convincing explanation of this phenomenon is the presence of an institutionalized choir, at least in the form of a small group of proficient singers attached to the hazzan in order to complement and lend variety to his soloistic performance. The innovation appears 'embryonically' at the time of Yannai, and fully-fledged in the Kalliric generation. It develops first within the qedussah and qerovah genres, and is then also taken over into the yozer complex (first into the zulat, later into the ofan). The choral element also assumes a new and standardized form, which includes a refrain strophe (pizmon). In the 9th century, newly composed 'choral pieces' begin to be inserted into older non-choral qedussah hymns. The process turns into hyper-tropy, and a reaction ensues- in which not the recent additions but the old components are discarded, and piecemeal at that, from these poetic complexes. When the lead in piyyut composition passes from the Near East to Spain, the solo-and-choir structures are not taken over. This accords with the explicitly documented efforts of the authorities to have the congregation participate in the service and to reduce the exclusive and showy role of the hazzan (thus also of the choir). The same attitude also prevailed in Italy and in the Ashkenazic area, and is similarly reflected by the piyyûtim created there.