Rosa Avzaradel (January 27, 1995)

A Flowering Debate: A Judeo-Spanish Song (not just) for Tu BiShvat

El debate de las flores (Debate of the Flowers) is the name provided by scholars to a long Judeo-Spanish (Ladino) song that was performed until recently in Northern Morocco around the festive table of Tu BiShvat, the fifteenth day of the month of Shvat known also as “the new year of the trees.” This celebration of the beginning of the agricultural cycle at the end of winter is a relatively newcomer to the Jewish calendar, going back “only” to Mishnaic times. However, present-day celebrations of this holyday among Sephardic and Oriental Jews with a festive meal similar to the Passover seder developed among kabbalistic circles of Safed only in the seventeenth century. The seder for Tu BiShvat appears for the first time in Sefer Hemdat Yamim (Izmir, 1730/1), a compendium of contested authorship (among them Sabbatean; for the Tu BiShvat seder see, Huss 2019) that nevertheless exerted great influence on modern Sephardic and Oriental Jewish ritual practices. This influence is clearly reflected in the preface to the chapbook called Conplas de Tu biShvat (Salonika 1800, 1801) containing a long copla by Rabbi Yehuda bar Leon Kal'i of Salonika (d. 1782) to be performed on the night of this holyday (as the title specifies “que usaron a cantarlas en la noche de Tu biShvat”). On the occasion of the publication of the Moroccan version of El debate de las flores in the JMRC’s publication by Susana Weich Shahak, Cada Año Mijorado: Judeo-Spanish Songs for the Year Cycle, it is worthwhile to revisit this unique song in its wider historical and cross-cultural context considering the availability of a wealth of versions in manuscript, printed and oral sources (for an exhaustive list of written sources, see Romero 1976: 282; Perez n.d. adds more versions to Romero’s checklist).

El debate de las flores has been classified as a copla, a genre of Judeo-Spanish songs, many of which are linked to the Jewish annual cycle of holydays. In the song various flowers boast of their virtues to demonstrate that each of them has the merit to praise God. It is a text based on ancient and universal poetic schemes centered on debates, schemes that also appear more than once in the Sephardic repertoire (see especially Refael 2004: 139-158). The theme of the debate between flowers is found in medieval Hispano-Arabic and Maghrebi poetry as well as in the poetry of the seventeenth-century Spanish siglo de oro and contemporary Algerian traditions (Abenójar-Sanjuán 2024) and also in the neo-Greek poetry of the Balkans (Armistead and Silverman 1968). El debate de las flores emerged therefore from a rich multicultural poetic and musical background that can be traced back to the medieval period.

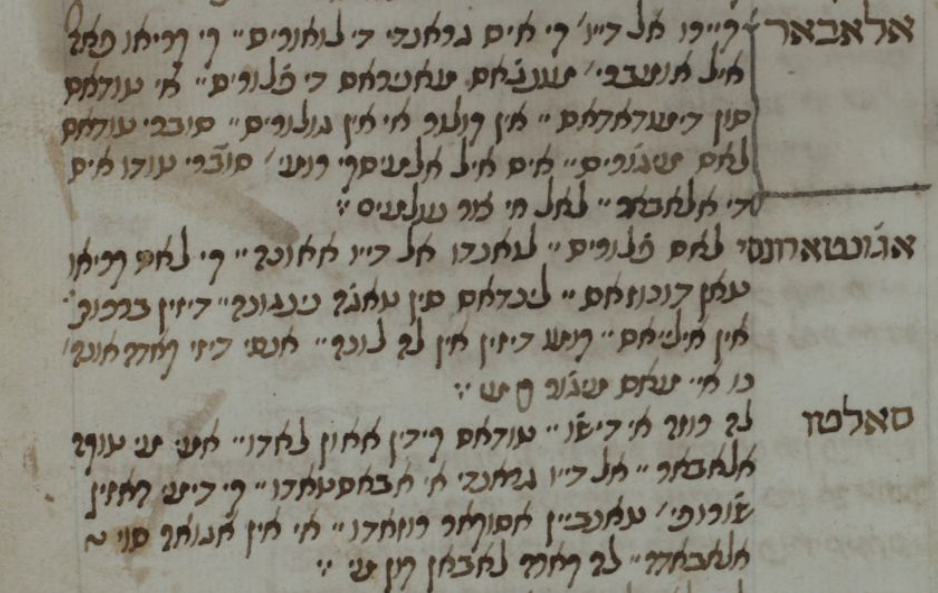

The Sephardic copla El debate de las flores has been assiduously documented from the early eighteenth century onwards. The most complete and ancient versions appear in the important piyutim manuscripts of the hazzanim (cantors) of the Hacohen family of Sarajevo, Moshe ben Mikhael Hacohen, who officiated at the Levantine synagogue in Venice, and David Behar Hacohen (British Library, Ms. 26967 titled Ne’im zemirot, dated in 1702; National Library of Israel Ms. 413, titled Pizmonim, shirot vetishbaḥot, dated in 1794). In her path-breaking studies of El debate de las flores, Romero (1976; 1988: 147-156) edited versions from a chapbook from Salonika (c. 1815) and from the 1794 manuscript (titled Cantiga delas rosas). Based on Molho (1960: 179-182) Romero tentatively attributed the song to Rabbi Yehuda bar Leon Kal'i of Salonika, an ascription that cannot be confirmed.

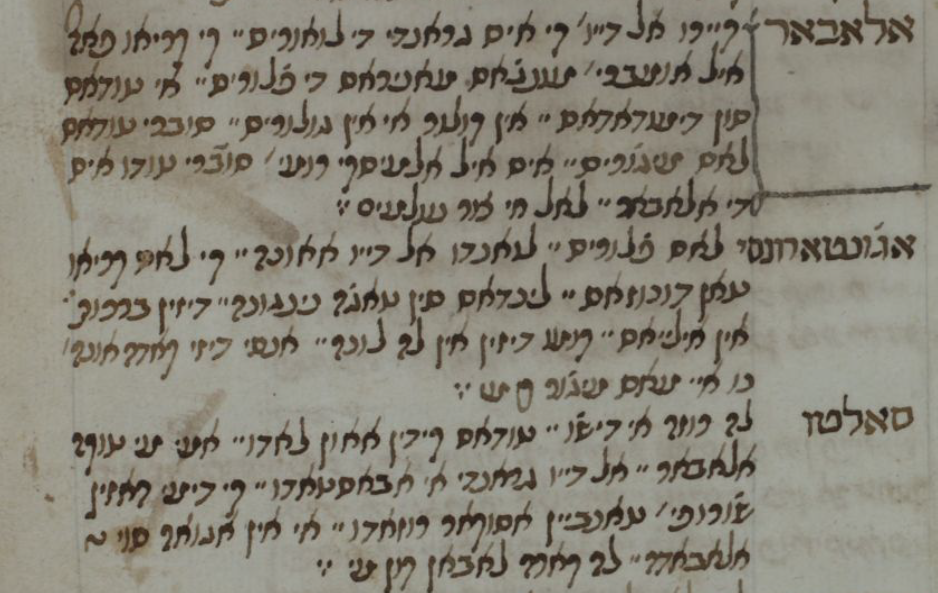

Figure 1: Opening of Cantiga sobre los [sic!] flores. Ms. British Library 26967, fol. 153b

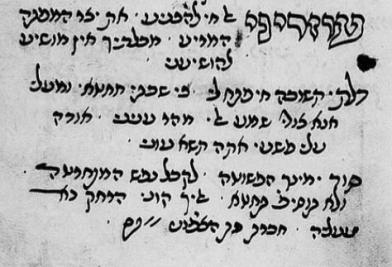

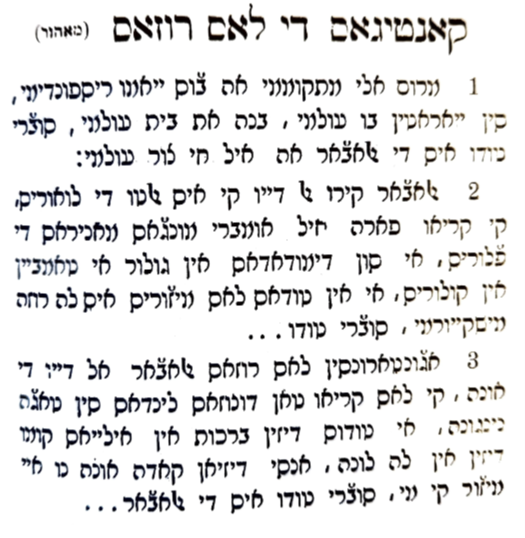

Three different, but related, versions of El debate de las flores appeared in print since c. 1800. The first version, stemming from the above-mentioned manuscripts, appeared with the title of Cantigas [sic] de las rosas in prints published in Istanbul (or originating in the city) since the beginning of the twentieth century. These prints include a loose leaf from c. 1900 (see Romero 1992, no, 176); Siftei renanot, cantigas delas rosas y unos pizmonim (Constantinople: Arditi, 1902, pp. 11-14); Sefer renanot ([Jerusalem]: Biniyamin Refael ben Yosef, 1908, pp. 2-6); and El buquieto de romansas (Istanbul: Biniyamin ben Yosef, 1926, pp. 5-8). These versions attribute the song to the holyday of Shavuot rather than Tu BiShvat. Moreover, they all open with a stanza from a trilingual poem (Hebrew, Ladino and Turkish) whose last line, “Sobre todo es de alabar / al Hay Tzur Olamim” (in the earliest manuscript version) becomes the refrain after each stanza.

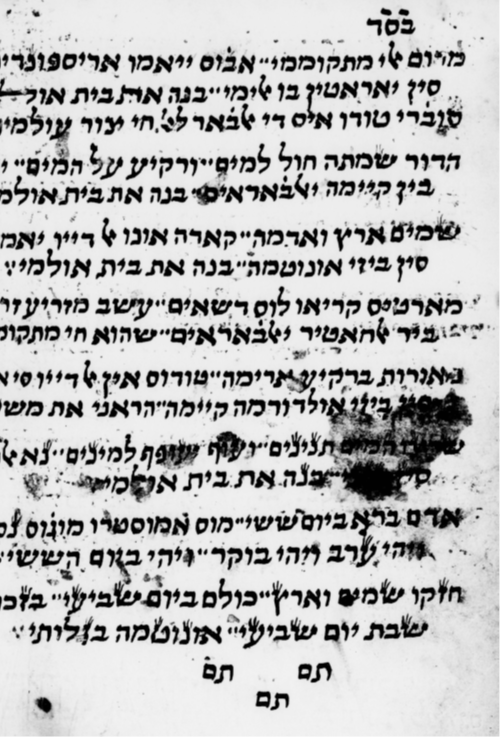

Figure 2: Opening of Cantigas de las rosas, in: Sefer renanot, 1908, p. 2

The second version of El debate de las flores is characteristic of chapbooks published exclusively in Salonika, the earliest of which is dated by Romero in 1815. These Salonika versions, all titled Conplas de las flores, appeared in no less than five editions throughout the nineteenth century. They all reproduce a text opening with the verse “Ya se ajuntan todas las flores / ya se ajuntan todas a una” and have the same bilingual refrain as the versions from Istanbul. Only from 1830 onwards the chapbooks from Salonika in which the song appears are titled Conplas de Tu BiShvat (earlier prints lack title page).

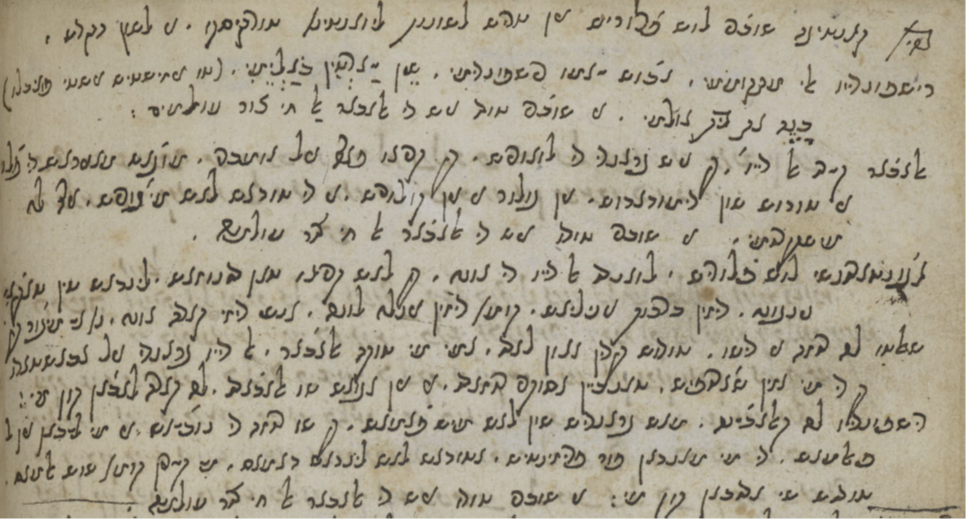

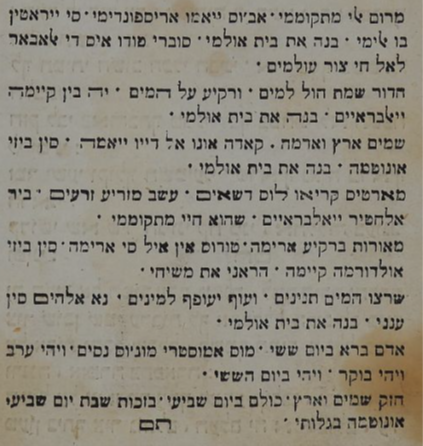

A third version of El debate de las flores, usually untitled, is the Moroccan one. Its earliest version appears in fols. 15a-b of Ms. 8o 3716 of the National Library of Israel, a compilation of piyutim by the poet Shlomo ben Moshe Tov Elem. It opens with the stanza “Alabar quiero al Dio que es grande de loores” that corresponds to the second stanza of the old manuscripts and the Istanbul versions: “Alabar quiero al Dio que es alto de loores.” Tov Elem’s compendium was written down over several years in Gibraltar and Tetuan during the early nineteenth century; the latest date mentioned in it is 1826/7. Tov Elem’s version lacks, as do the Salonika versions, the opening multilingual stanza appearing in the Istanbul prints. There is no printed documentation of El debate de las flores in Morocco until the second half of the twentieth century (see below). It appears though that its transmission was mostly made through manuscripts. One such specimen was published by Gladys Pimienta (2ooo) from a handwritten notebook of piyutim and Judeo-Spanish songs by Yaakon Attias of Tetuán dated around 1915 and belonging to the Ma’aleh Adumim Institute. What strikes the reader is that this early twentieth century version is almost word by word identical to the one in the Tov Elem manuscript, attesting to a written transmission that also explains the much later ethnographic evidence (see below).

Figure 3: Opening of El debate de las flores in Shlomo Tov Elem’s manuscript, National Library of Israel, 8o 3716, fol. 15a (19a in new pagination)

It is worth noting the connection between El debate de las flores and sacred Hebrew poetry (piyut), not only because it appears almost exclusively in collections of piyutim in all the traditions but also because its bilingual refrain derives from a piyut. The title of the oldest version (1702; see Figure 1 above), reads Cantiga sobre los [sic!] flores en tres leshonot levantino, turquesco y leshon hacodesh, i.e. “Song about the flowers in three languages Levantine [Judeo-Spanish], Turkish and holy tongue [Hebrew].” In this early version the poem opens, as we have noticed in reference to the Istanbul versions, with a trilingual stanza (to which this title refers, while the rest of the song is in Judeo-Spanish) whose last verse becomes the refrain of the song. This stanza, maintained in Istanbul versions of El debate de las flores read as follows:

Merom Eli mitkomemi,

A vos llamo, respondeme.

Sen yarattin bu âlemi

Bene et bet ulami.

Sobre todo es de alabar

al Hay Tzur ‘Olamim

Our translation:

From heavens, my God, restore me [compare Job 27: 7],

I call you, answer me.

You have created this world

Rebuild my House of Worship [i.e. the Jerusalem Temple].

About everything one should praise

the Living God, Rock of Eternity

This stanza belongs to the opening of a macaronic piyut (Hebrew, Turkish and Judeo-Spanish) on the seven days of creation appearing in the Ms. NLI 413 of 1794. This piyut there is titled Cantiga de siete días de la semana (fol. 111a), and significantly precedes the Cantiga delas rosas. This macaronic song appears also in Ms. Yeshiva University 1125 titled Pizmonim veshirim copied between 1852 and 1857 by Barukh Moshe Moreno of Monastir (today Bitola in Northern Macedonia). It was published as Ben Meshek (acronym of Moshe Shabbat Kamḥi) in Salonika, 1857 (see Figures 4 and 5). The possibility that the author of this piyut borrowed the first stanza from El debate de las flores is much less probable.

Figure 4: Merom Eli Mitkomemi in Ms. Yeshiva University 1225

Figure 5: Merom Eli Mitkomemi in Ben Meshek, Salonika 1857

El debate de las flores in all its versions consists of stanzas of eight lines each with the above-mentioned refrain in Hebrew. The rhyming scheme of most of its twenty stanzas (as an average) is abcbdbbx, whereas “x” corresponds to the Spanish word “mí” that rhymes with the refrain in Hebrew, “[ola]mim.” This pattern, as Romero remarks (1988: 148), is unique in the Judeo-Spanish repertoire. However, it is found in the piyut repertoire in songs of the muwashshah type (in Hebrew shir ezor or “girdle song” as already noticed by Refael 2004: 156-7) where the last line of the stanza rhymes with the refrain, usually a Biblical verse. In addition the Salonika version ends with a stanza praying for the hastening of messianic redemption, a central topic of the early modern Ottoman piyut.

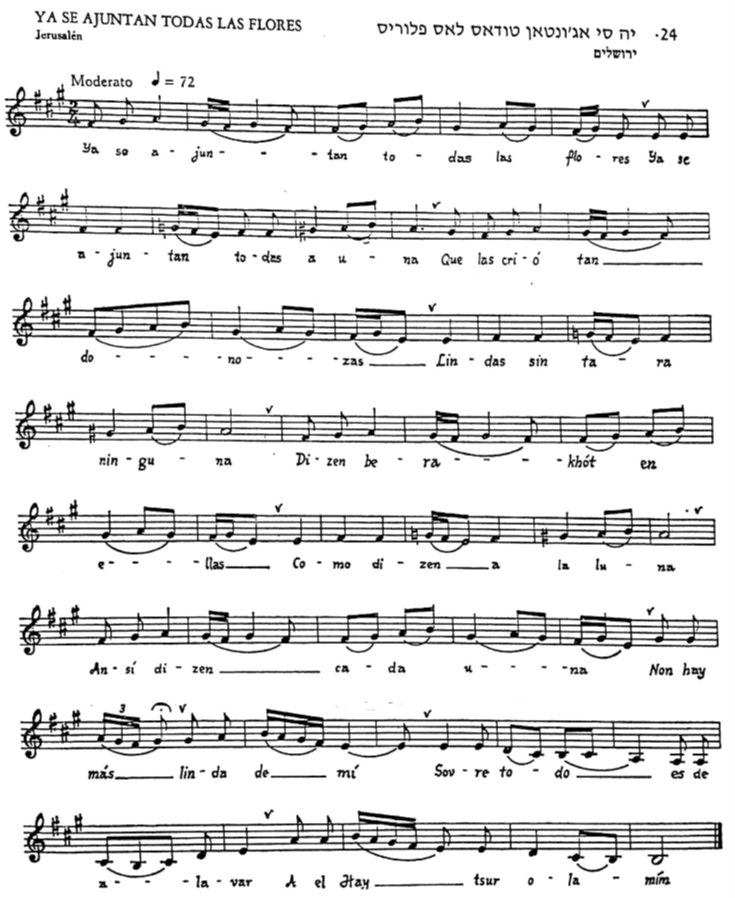

El debate de las flores was still sung in the Eastern Mediterranean until the early-twentieth century as is shown by the consistent mention of the Turkish makam Mahur in its header (see Figure 2 above). Evidence of this musical tradition of El debate de las flores is scant. A musical transcription in Isaac Levy’s Antología de la liturgia judeo-española, vol. 4, no. 24, pp. 35-39 (Figure 6) documents a melody whose descending direction indeed points to makam Mahur. Although marked as recorded in Jerusalem, the text of Levy’s version, opening on “Ya se ajuntan todas las flores,” coincides with the Salonika prints. No sound recording of this version is available at this point.

Figure 6: Melody of El debate de las flores in Isaac Levy (1965)

Another precious musical document of El debate de las flores as it was sung in an Eastern Mediterranean Sephardic community are the recordings by Rosa Avzaradel (b. 1910), a unique song-bearer of the Judeo-Spanish tradition from the island of Rhodes. Susana Weich Shahak recorded two versions of El debate de las flores from Avzaradel in Ashdod on January 5, 1994 and on January 27, 1995 (found now in the Sound Archives of the National Library of Israel).

In the first of these recordings the singer recites the text before singing it, attesting that she does not remember “all the flowers” but that her mother did. Her fragmented version shows though interesting textual variants. This is therefore a testimony that El debate de las flores was orally transmitted among women in the Eastern Mediterranean at least until the early twentieth century. Avzaradel’s version has a distinctive aksak nine-beat rhythmic pattern of 2+2+2+3 similar to the Turkish usul karşılama or the Greek zeïbekiko. In the absence of a percussion accompaniment her rendition of this pattern is somehow loose. This rhythmic feature of the melody points to the probable adaptation of a local melody from Rhodes or the nearby city of Izmir to El debate de las flores that differs from the one in makam Mahur from Istanbul.

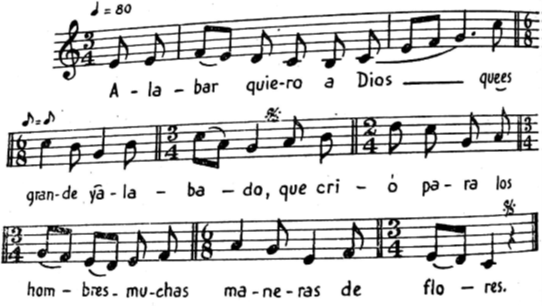

The survival of the music of the Moroccan version of El debate de las flores in oral tradition is more conspicuous. This traditional melody, published now by Weich Shahak in our website, was recorded and notated by Arcadio de Larrea Palacín (1954: 164-171) in two versions (for one of them see Figure 7) based on his early 1950s fieldwork in North Morocco. Remarkably, Larrea Palacín copied two of the three textual versions he published from manuscripts, further evidence that in Morocco the transmission of El debate de las flores was chiefly a written one.

Figure 7: Moroccan melody of El debate de las flores according to Larrea Palacín (1954: 164)

The study of El debate de las flores deserves reflection about the poetic and musical exchanges between Sephardim from the two ends of the Mediterranean. The Eastern text appears to have migrated to Morocco through various routes, either manuscript, printed or oral, though the time of transmission and the identification of the agents involved in this process remain opening questions. The bilingual refrain, however, conceals that the opening trilingual stanza of the older manuscripts was indeed integral to El debate de las flores. The version by Shlomo Tov Elem, who is a clear “suspect” in this process of transmission from East to West, is already “hispanized,” shifting the Turkish terms of the Eastern versions, especially the names of the flowers, to Castilian and/or Haketía (North African Judeo-Spanish) ones. This East to West route in the transmission of El debate de las flores, however, should not be taken as a definitive one. The striking Western Algerian Arabic parallels of El debate de las flores published by Abenójar-Sanjuán (2024: 685-692) raise another hypothesis, that a much earlier peninsular or North African original lies behind the Ottoman Judeo-Spanish versions. A detailed comparative examination of all Sephardic versions of El debate de las flores that will take into consideration the agency of its transmitters and performers may shed more light on this matter in future studies.

The connection of El debate de las flores with the festive table of Tu BiShvat also appears to be a later tradition as most early Eastern versions are, as we have noted, for Shavu’ot. In addition, the Moroccan version contains new stanzas that are not found in the Eastern versions and were probably created by local singers-poets. Eventually, a wider fashion of parodying El debate de las flores with debates on more humorous topics set to the same poetic format of this copla developed in Morocco (Weich Shahak 2012).

Finally, it is worth mentioning other debate-based coplas addressing Nature that are related to El debate de las flores and, unlike it, definitely associated with the festivity of Tu BiShvat, El debate de los frutos (Romero 1976) and El debate de los frutos y el vino (Debate between the fruits and the wine; see Romero 2011, 2014). Both songs were also printed back-to-back in most chapbooks from Salonika and they bear significant similarities in terms of their poetics and form.

The Eastern version of El debate de las flores with English translation can be found in a special online project of the Sephardic Studies Program at the University of Washington in Seattle (see however above, our amendment to the translation of the opening stanza). We are thankful to our colleagues in Seattle for this important contribution to the study of the Sephardic coplas. The facsimile version of El debate de las flores from Sefer renanot (1908) and its translation to Hebrew are available in Refael (2004: 144-152). A Hebrew translation of the Moroccan version by Avner Perez appears online (Perez, n.d.) as well as in an educational publication of Sephardic songs (Weich Shahak, Perez and Seroussi 1991).

For a Spanish version of this Song of the Month see,

References

Abenójar-Sanjuán, Óscar. 2024. “Versiones hispánicas de El debate de las flores a la luz de las magrebíes e hispanoárabes,” Nueva revista de filología hispánica 72(2), 669-697.

Armistead, Samuel G. y Joseph H. Silverman. 1968. “Las complas de las flores y la poesía popular de los Balcanes,” Sefarad 28: 395-398.

Huss, Boaz. 2019. “Ha-etz ha-neḥmad ben Yshay ḥay al ha-adamah: ‘Al mekoro ha-Shabta’i shel seder Tu BiShvat” (On the Sabbatean origins of the Tu BiShvat seder), Sefer zikaron le-Prof. Meir Benayahu = Meir Benayahu memorial volume: Studies in Talmud, Halakhah, Custom, Jewish History, Kabbalah, Jewish Thought, Liturgy, Piyut, and Poetry, ed. Moshe Bar-Asher, Yehudah Liebes, Moshe Assis and Yossef Kaplan. Jerusalem: Carmel, vol. 2, pp. 909-919.

Larrea Palacín, Arcadio de. 1954. Canciones rituales Hispano-Judías: Celebraciones familiares de tránsito y ciclo festivo anual. Madrid: I.D.E.A.

Levy, Isaac. 1965. Antología de liturgia judeo-española, vol. 4. Jerusalem: The Author.

Molho, Michael. 1960. Literatura sefardita de Oriente. Madrid-Barcelona.

Perez, Avner. n.d. “Hacoplas vikuaḥ ha-praḥim le-Tu biShvat” in https://folkmasa.org/av/kolpirhe.htm

Pimienta, Gladys. 2000. “El kantoniko de haketia: El debate de las flores,” Aki Yerushalayim 21(64): 32-36. https://folkmasa.org/av/av05mc3.htm

Refael, Shmuel. 2004. Asaper shir: meḥḳar be-shire ha-ḳoplas shel dovre ha-Ladino be-liṿyat mivḥar targumim mi-Ladino le-ʾIvrit. Jerusalem: Carmel.

Romero, Elena. 1976. “Complas de Tu-bišbat,” In Poesía: reunión de Málaga de 1974. Ed. Manuel Alvar. Málaga: Diputación Provincial, vol. 1, pp. 279-311.

Romero, Elena. 1988. Coplas sefardíes: primera selección. Córdoba: El Almendro.

Romero, Elena (en colaboración con Iacob M. Hassán y Leonor Carracedo). 1992. Bibliografía analítica de ediciones de coplas sefardíes. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

Romero, Elena. 2011. “La copla sefardí de El debate de los frutos y el vino y sus ecos en la tradición oral” in Estudios sefardíes dedicados a la memoria de Iacob M. Hassán (z”l), Elena Romero and Aitor García Moreno (eds.), Madrid: CSIC, pp. 491-524.

Romero, Elena. 2014. “Otra versión sefardí manuscrita de El debate de los frutos y el vino,” Sefarad 74: 427-452

Weich-Shahak, Susana, Avner Perez and Edwin Seroussi. 1991. Zer shel shirei ‘am mi-pi yehudei Sfarad. Recordings and transcriptions by Susana Weich-Shahak, translations to Hebrew by Avner Peretz, edited by Edwin Seroussi. Jerusalem: Renanot, Institute of Jewish Music and the Ministry of Education and Culture.

Weich-Shahak, Susana. 2012. “Debates coplísticos judeo-españoles,” eHumanista 20: 402-415.