Yaakov Huri: An Iraqi Cantor in the Edith Gerson Kiwi Archive

The recorded collection of the Baghdad-born cantor Yaakov Huri is one of the largest repertoires Edith Gerson-Kiwi recorded from a single individual. This repertoire serves as a paradigm for evaluating the scope of Kiwi’s ethnography, its contribution to contemporary research as well as the nature of the relationship between her and her research partners. The intimate relationship between Kiwi and Yaakov Huri and their mutual respect that becomes clear from our research challenges perceptions informed by asymmetrical power relations dominating the encounters between European ethnomusicologists and their subjects of inquiry in Israel.

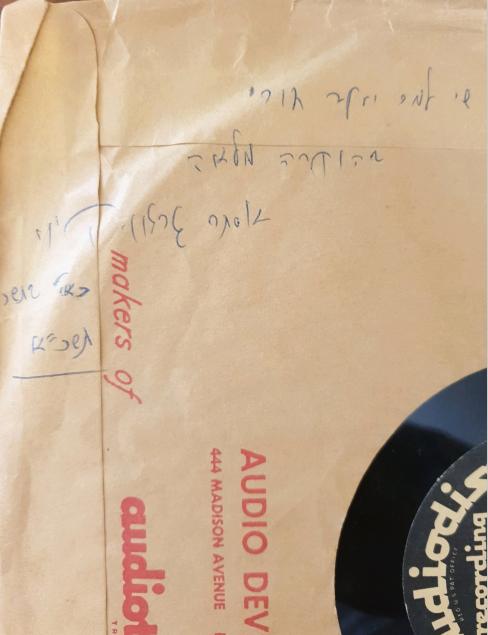

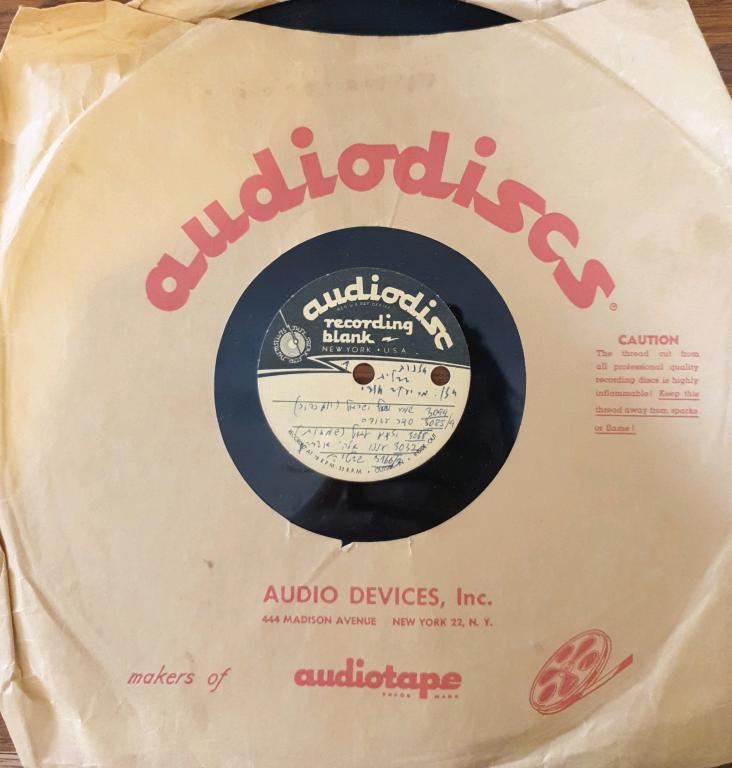

Our research on the Yaakov Huri repertoire as documented by Kiwi consisted of several stages. Zooming into Huri’s recordings within the Kiwi archive was a first stage because these recorded documents were scattered and not in a chronological order. Each unit of recording (originally a 78rpm record or a magnetic tape) included several items. Therefore, the second stage consisted of separating the items into single recordings that allowed for easy access to each of them. Sorting out other sections of the Kiwi archive for Huri materials (diaries, letters) comprised the third stage of research. We also sorted out other archival recordings by Huri or related to him. The last stage consisted of an ethnography. We were fortunate to locate Huri’s two children in Jerusalem, Ruth and David Huri, who kindly shared with us orally their memories of their father as well as documents related to him and photographs. In addition, the family kept a precious gift given by Kiwi to their father, a vinyl record with a copy of his recordings with a very personal dedication by Kiwi.

The vinyl record with the dedication by Kiwi

This entry consists of two sections. We open with a biographical profile of Yaakov Huri based mostly on information supplied by his children. As expected, this appreciation of his life is marked by fond memories and nostalgia for their father. Yet, it provides a profile of the man, his ideals and his standing in society. We supplemented heir detailed testimony with a brief appreciation of Huri by the distinguished cantor Moshe Havusha of Jerusalem.

A detailed description of Kiwi’s ethnography of Huri follows this biography. Here we focus on the evolution of Kiwi’s engagement with Huri, her methodology and on the results of this ethnographic encounter from the perspective of the present. A list of Kiwi’s recordings of Yaakov Huri is included in a separate file.

From Baghdad to Jerusalem: Yaakov David Huri’s biography

Yaakov David Huri was born in Baghdad in 1914 (no precise date available) to a large family, and was the youngest of all his brothers and sisters. Huri acquired his education in the Beit Midrash of Baghdad and was considered a child prodigy. By 1931, when he was only seventeen years old, he was already ordained as rabbi. Huri belonged to the Zionist sector of the Jewish community. This sector, unlike the yeshivah students that were supported by the Jewish community, worked during the day for their livelihood, and when they finished their work, they studied Torah. Huri’s dedication to cantorial studies demanded that he deepen his study even further.

The Huri family, Baghdad

After being ordained as rabbi, mohel (i.e. certified for carrying out circumcisions) and ritual slaughterer, Huri received an invitation to from the rich Baghdadi Jewish community in India. At the same time, his brothers asked him to join the family business because of his skills in mathematics. Despite his brother's requests, Huri decided to accept the offer overseas without telling his family about his departure due to the fear that they would try to dissuade him from his decision. He packed his belongings and left at dawn leaving a written message for his family. Indeed, Huri became rabbi of the Baghdadi community in India, and his name went out as a young and prominently talented cantor.

Huri was an ardent Zionist and his dream was to immigrate to Eretz Israel. Having amassed a small fortune from his work at the Jewish community in India, he finally set out to immigrate to Palestine through the Suez Canal. In 1936 he boarded a ship in the direction of Palestine at a time when the British authorities had restricted Jewish immigration severely. Huri obtained the sponsorship of Prof. David Yellin, one of the most respected figures in the Jewish community of British Palestine and close to the colonial authorities. In protest against the policy of discrimination, Huri boarded the ship in pajamas to spite the British.

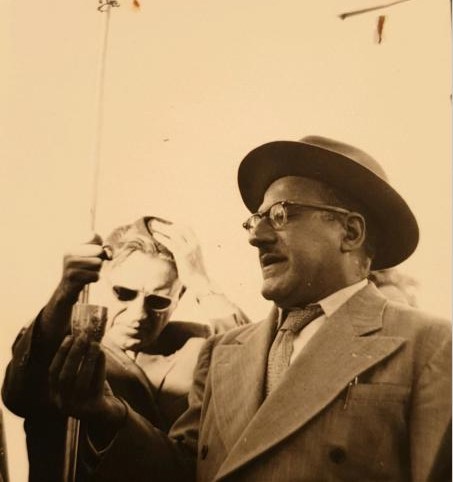

Huri on the ship on the way to Eretz Israel

Once in Jerusalem, Huri used his savings to open a clothes’ store in the Mea Shearim quarter. Over the years, he received lucrative job offers to officiate as cantor in Jewish communities outside Israel, for example in Mexico and London. These offers came under the auspices of the prestigious Sassoon family from Baghdad, but he refused to accept them because of his Zionist leanings. He claimed that those who settled in Eretz Israel cannot leave it. However, Huri fiercely resisted the Zionist melting pot; he was proud of the tradition of his ancestors and worked hard to preserve it. Also, when he was offered to change his family name, he claimed that there was no need for a change because that name appears in the Bible. He remained faithful to his Baghdadi roots and refused to negate his past, an unusual stance in the Zionist ideological landscape of that time whose main tenet was the “negation of Diaspora.”

Huri became acquainted with his wife Sima when he was in Palestine and she was still in Baghdad. Sima's family used to travel back and forth from Palestine to Baghdad. While attending school back in Baghdad, Sima craved to return to Israel. She heard Huri settled in Israel, and in 1938 she contacted him. The two were engaged, which led Sima and her mother to settle permanently in Eretz Israel, and in 1940 they married in Jerusalem. Sima was a liberal woman, but this did not bother Huri as he did not believe in forcing religion observance on others.

Sima Huri in a photograph she sent from Baghdad to Yaakov, May 14, 1938

Wedding of Yaakov and Sima Huri, Jerusalem, 1940

During the 1948 War of Independence Huri volunteered at a hospital. With the establishment of the State of Israel he felt that he could no longer hold to his clothes’ shop due to the precarious economic situation. He therefore closed his business and began working for the Jerusalem Municipality’s treasury, where he worked until his retirement.

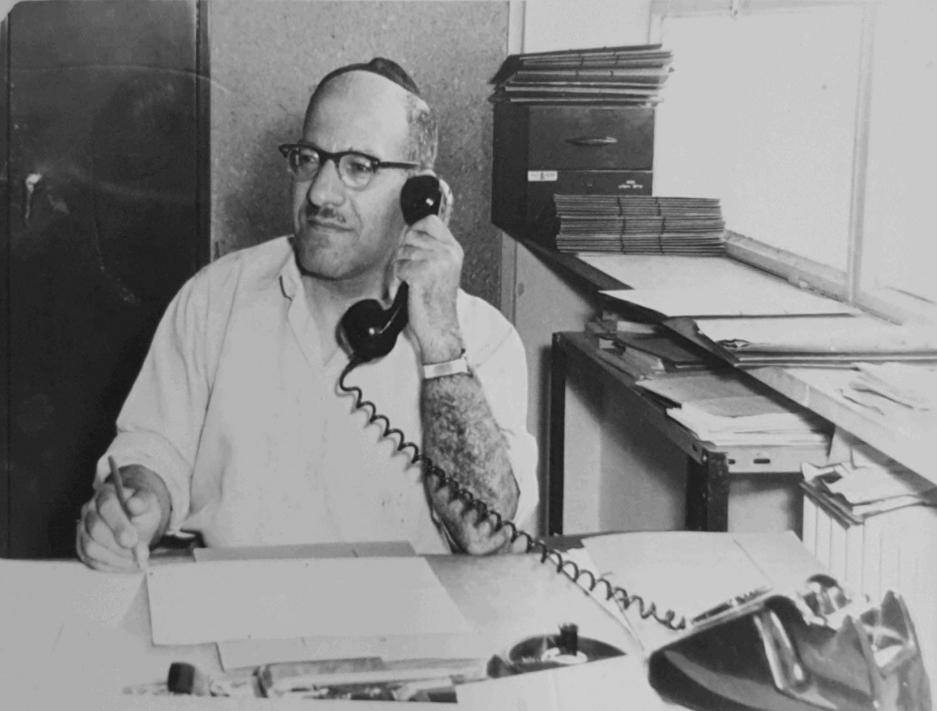

Huri at his workplace, the Treasury Department of the Jerusalem Municipality

Huri and his family lived in the Mahaneh Yehuda neighborhood, on HaShikma Street. At that time (1940s) this neighborhood was considered as a prestigious one. Moreover, located in this neighborhood was the Minhat Yehuda Synagogue, a spiritual and cultural center of the “Babylonian” (“bavlim” is how Iraqi Jews refer to themselves) Jewish community in downtown Jerusalem. According to his children, Huri was a “liberal” cantor in his approach to the liturgy and highly esteemed in the community. At Minhat Yehuda he worked alongside Gorji Yair (1909-1999), one of the most prestigious cantors of Baghdad who moved to Israel and was of a dynasty of leading cantors still active in Israel today. In addition, Huri began studying Kabbalah in Jerusalem alongside the great Iraqi kabbalist Rabbi Itzhak Kadouri (c. 1898-2006), both guided by Rabbi Yehuda Ftaya (1859-1942), one of the greatest masters of Kabbalah from Baghdad.

Huri was very involved with the Babylonian community and esteemed by its members. His neighbors and those around him had great respect for him as well as did the rabbinical leaders of the Babylonian community who valued his modesty, precise cantorial art and generosity. His authentic Baghdadi cantorial style seems to have been the main trait attracting people to him, as newly arrived immigrants from Iraq (from 1952 onwards) sought in Israel for a place where the musical tradition of their ancestors as they knew it was preserved. He also read the Torah swiftly, without embellishments, as was customary in Baghdad. He studied the parshah (weekly Torah portion) and prepared for reading in public each week aiming at performing it flawlessly.

Yaakov and his wife Sima with their children Naomi, Moshe and Ruthy

Huri was a sought-after cantor in Jerusalem synagogues, especially those with an Iraqi constituency, not only in his area of residence but in Jerusalem in general. He was also the cantor in the synagogue of the Chief Sephardi Rabbi of the State of Israel – Rabbi Yitzhak Nissim (1895-1981; officiated as Chief Rabbi from 1955 to 1972).

Remarkably, Huri was accepted as cantor not only by Babylonian Jews, but by other ethnic groups in Jerusalem, Greeks, Persians, Kurds and more. For the most part, Jerusalemites tended to attend synagogues whose style of praying was according to their families’ tradition, but Huri was widely accepted and loved by all. At one point, Huri became a cantor in the Beit Yaakov ve-Ohel Sarah synagogue of the Yanina community (Greek-speaking Jews, located in the Mazkeret Moshe neighborhood opposite the Mahane Yehuda market). He was so in demand, that there were certain situations in which he would lead prayers in one synagogue, and then walk to another one to read the Torah. The demand for him as a cantor was also a sign of respect for him. Although he worked hard as cantor to supplement his income, he did a lot gratis, out of a sense of public mission. Beyond his work as cantor, the community sought Huri's services in other areas and over the years he received many offers. For example, the Hevra Kadisha (burial society) offered him to work on its behalf, but he refused because of his aversion to politics and his great modesty.

Huri's circle of friends revolved mainly around the synagogue, with whom he walked around and talked after prayer. He also had many friends outside the synagogue from various circles. One of his well-known friends was the prominent Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (1920-2013), Chief Sephardic Rabbi (1973-1983) and political figure, whom he had known since his days in Baghdad.

His special relationship with Edith Gerson Kiwi fits his jovial personality. Kiwi connected with him after learning about his stature within the Babylonian community in Jerusalem and beyond. Their intensive work together (see details below) developed into a friendship. This intimacy was expressed in the fact that the Kiwis invited Huri to officiate in the marriage ceremony of their only son.

Huri officiating the wedding of Yoram, son of Edith Gerson-Kiwi. Jerusalem, June 1962.

Religion was the mainstay of Huri's life. He never read the Torah in order to demonstrate his proficiency compared to others, but out of a deep connection and desire to bring people closer to religion, especially secular people. He did not act out of coercion or a desire for aggressive persuasion, but out of a desire to try to show those around him the beauty of religious life. On Yom Kippur and on Rosh Hashanah, Huri established on his own initiative a special synagogue at Beit Ha'am on Jaffa Street. He took care of bringing all the necessary equipment, the prayer books and even a shofar blower paid by him. Huri stood every year on the long gallery of Beit Ha’am and lead the prayer from there. Women and men, young people and academics who could not find their place in any other community or synagogue in the city, would gather around him. From year to year the number of participants who came to these special services grew. Huri's goal was not to bring them back in repentance, but to facilitate the joy of the holyday for non-observant Jews and to create an atmosphere of “closeness of hearts.”

Huri saw a mission in an effort to stimulate the worshipers through singing, and therefore he was always careful to invest in his singing and would not decrease the volume of his voice or the level of his devotional intention (kavvanah) even after prolonged prayers or while fasting. As a rule, his dedication to the community was reflected in other activities in which he participated making sure always to attend the needs of people and help in times of stress.

One Friday, towards Shabbat, a couple arrived at his home. The woman was in advanced state of pregnancy and they asked Huri to marry them. Realizing that no one wanted to marry them due to the pregnancy, Huri married them without hesitation. In the same way, he took under his wings a child in the neighborhood who was adopted, and as a result, no one agreed to teach him in preparation for the bar mitzvah. Huri taught him without any question or doubt. He was a man who loved people, so the nickname "the angel" stuck with him among those around him.

His daughter Ruthie says that in the 1970s, Huri received a call from the Conservative Synagogue (opposite Paris Square in Jerusalem) to come and read a parashah for them, as they were eager to hear prayers in the styles of other Jewish denominations. Huri arrived accompanied by his daughter, and upon arrival he discovered to his surprise that men and women were sitting together during services. He looked at his daughter and asked her to explain the matter, and she told him that this was a non-orthodox community and that this was their practice. Although the joint seating of men and women in the synagogue was contrary to the tradition in which he was raised, he agreed to read the parashah for them. Despite the uneasiness he felt regarding this matter, he claimed that they too were Jews and therefore chose to honor their invitation.

Huri was an energetic, hardworking and valued person. In addition to Torah study, he always worked and earned a decent living. Put differently, he never profited from his religious knowledge and functions. His agenda was full: he would go to work early in the morning, after getting up to pray at daybreak. At noon he would return from work to eat, and from there went to his studies at the yeshiva. Afterwards, in the evening he would go to officiate in a wedding ceremony. Religion was the center of his life, but it was important for him to combine family life and hard work for a living.

Despite Huri’s growing religious observance over the years, he did not believe in coercion, and therefore did not impose his religious lifestyle on his children. He advocated for generosity, love of children and family as a guide to a virtuous life. These universal values mattered him more than values dictated by religious norms.

Another value that was important for him to instill in his children and those around him was the respect for books. He worked hard and chose to invest his money in books, and he did not take his purchase power for granted. In every book he bought, he wrote the following dedication out of appreciation for the book and the written letter: "I purchased this book for the amount of____ from my own capital in honor of my Creator."

Huri strongly opposed deeds that were done only ostensibly, and advocated engaging in essence. He did not agree to be called “rabbi” or invest in external appearances, such as wearing fancy suits. He also vehemently opposed the commercialization and politicization of religion, and therefore disliked people who used the Torah for political purposes. He received an offer to belong to the Sephardic religious party (SHAS) in exchange for a senior position, but he vehemently refused to take part in political activities. He also refused to disclose to others which political party he supported.

Huri was not only active in the religious community, but also engaged in volunteer activities throughout his life. After retiring early from his job at the Jerusalem Municipality, he volunteered to take the responsibility of issuing identity cards throughout the West Bank. His command of three languages English, Arabic and Hebrew led him to this job in which he was highly esteemed.

An appreciation of Huri by the distinguished cantor Moshe Havusha, a grandchild of Gorji Yair, Huri’s associate at the pulpit in the Minhat Yehuda synagogue, verifies some of the features of Huri’s personality as expressed by his children. Havusha, who as a youngster knew Huri as a friend of his father, describes him as “a happy and joyful person” who had a “noble soul.” He was sent by Rabbi Salman Hugi Aboudi (1894-1973), a dayan (rabbinical judge) of Baghdad and the city’s last chief rabbi, to serve as cantor in Mumbay (Havusha was not absolutely sure about this detail). Huri did not dress as a rabbi, but held marriage ceremonies and acted as a “part-timr rabbi.” People liked his cantorial style because he did not prolong the prayers unnecessarily. He was cantor at the Ohel Rachel Synagogue, a Baghdadi synagogue on David Yellin Street. This synagogue was founded in 1937 by Baghdadi Jews and became second only to the older Minhat Yehudah Synagogue. It was named after the synagogue of the same name in Shanghai, endowed by Yaakov Elias Sassoon in memory of his wife Rachel. Havusha was aware of Huri’s recordings (“he recorded everything”), and stressed that Huri recorded one Hebrew song, “Hay, hay yodu hay” that “no one else had recorded.”

Kiwi’s ethnography of Yaakov Huri

For the moment we do not know the precise circumstances that led to the encounter between Huri and Kiwi. Kiwi’s vast recorded collection shows a certain consistency in terms of the selection of her research collaborators. She followed the more or less accepted convention of classifying the “Oriental” Jews according to “’edot” (ethnic communities, sing. ‘eda), a norm that goes back to the field work of Abraham Zvi Idelsohn in Jerusalem during the first two decades of the twentieth century. This social compartmentalization is based on geographical and linguistic criteria. It separates between Judeo-Spanish, Arabic, Persian and other “minor” languages. Within these linguistic groupings, she distinguished between North African, the Levant (Land of Israel, Syria, Turkey) and the rest of the Middle East (Iraq, Kurdistan, Yemen) up to Iran and the Indian subcontinent.

These socio-cultural units adhere also to the self-perception of the “Oriental” Jews themselves, as these perceptions are reflected in the synagogues associated with each of these groups as well as in other institutions such as burial societies. Obviously, such sharp geo-linguistic distinctions obliterate more discrete sub-cultural units within each ‘eda, and therefore discards local musical lore in favor of a generic repertoire related to large social conglomerates. More consequentially, hybrid musical configurations are sidelined, leading to the essentializing of the “music of the ‘edot”, a nomenclature that was favored by the Israeli folkloristics and media.

To cover such vast regional and linguistic areas, Kiwi selected, as was the norm with Idelsohn and later Israeli ethnographers, what used to be called “key informants.” These are individuals who are recognized as true representatives of the musical lore of an entire “’eda.”

Kiwi’s archive includes a staggering 640 recorded items, by the lowest count, by Yaakov Huri alone or by him accompanied by a group to singers. Recordings started on June 9, 1958 and continued on a regular basis until November 23, 1959 (with a break between March and November 1959), a total of sixteen intensive recording sessions. The aim of these sessions was clear: to cover systematically the entire repertoire Huri knew. It included five main categories:

- the entire liturgical year cycle of the synagogue;

- songs for the life cycle (circumcision, bat mitzvah and wedding);

- domestic ceremonies (end of the Sabbath, Passover Seder)

- songs of pilgrimage to holy sites;

- readings of sacred texts, mostly from the Bible but also from the Oral Law (Mishnah) and the Zohar (Book of Splendor),

The dates of the recordings are: 9/6/58, 26/6/58, 3/7/58, 13/7/58, 14/7/58, 24/8/1958, 2/9/58, 9/9/58, 26/10/58, 4/1/59, 25/1/59, 1/2/59, 8/2/59, 15/2/59, 1/3/59, 23/11/59 (for a detail see the appendix at the end of this article).

We do not count in these formal sessions a special occasion, a birthday party in honor of Kiwi’s father, Dr. Reuven Kiwi, on his eightieth birthday held at Kiwi’s home on the end of the Sabbath, February 28, 1959. Kiwi obviously invited Huri and Yehezkel Batat, an assiduous companion of Huri during the recording sessions, to officiate in the ceremony of Havdalah, the ending of the Sabbath. This ceremony was recorded and comprises the only “live” recording of an actual event. One should notice that the day after the party Huri was back in Kiwi’s studio.

Kiwi returned to record Huri occasionally in later years. Most of these recordings were specific Biblical readings that Kiwi used as illustrations for her lectures in academic conferences as well as for radio programs. At least four of these additional sessions appear in the archive on the following dates: 17/3/63, 16/7/64, 9/8/64, 13 or 16/8/68 (it is not clear from the catalogue). A final session was held many years later, on July 15, 1981. We do not know the circumstances of this late recording.

Huri's recordings are available in our website, here.

Huri's recordings are available in our website, here.

See also the project on the Edith Gerson-Kiwi legacy.

See also the project on the Edith Gerson-Kiwi legacy.

The Yaakov Huri's recordings project was carried out within the grant “From Berlin to Jerusalem and Back - The Letters of German-Jewish Musicologist Edith Gerson Kiwi (1908-1992),” a joint venture of the Europäisches Zentrum für Jüdische Musik (Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien Hannover, Germany) and the Jewish Music Research Centre (Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel) in the framework of the Research Cooperation Agreement Lower Saxony – Israel (Aktenzeichen: A125614) of 2016-2020.