Childhood and early musical career

Yossef (Yusuf) Zaarur (يوسف زعرور) was born in Baghdad in either 1902 or 1896—per Israeli immigration documents—to a family of ten children. As with most Baghdadi Jews, Zaarur attended synagogue services and traditional family celebrations from an early age, which exposed him to the richness of the religious vocal repertoire of his community and to the Iraqi Arab singing style. Yossef is not to be confused with his much older cousin, Yusuf Zaarur al-Kabbir (“the Great”, 1867?-1943?), one of the first qanun players in Iraq. Zaarur al-Kabbir was a source of inspiration for the younger musician. He owned the modern-styled coffeehouse Sawwas on Maydan Square in the entertainment strip of Al-Rashid Street, and later the Alef Layla nightclub (Kojaman 2001: 45).

Yossef’s father, Meir Zaarur, was a watchmaker and jeweler. Although fond of music, he was not pleased to see his son’s early inclination to music. According to family lore (see recorded interview in Hebrew with Zaarur’s daughter), when Yossef was eight years old and had become passionate about music, he tried to build a musical instrument similar to the qanun by himself. This infatuation with music angered Yossef’s parents, who feared that music making would hinder his general education and the study of Torah in the religious school he attended. Although his father confiscated the instrument, the boy did not give up on his passion for music; eventually his will prevailed despite the family’s reticence. This generational tension between well-to-do Baghdadi Jewish families and their youngsters who loved music and wished to become professional musicians, is documented in other cases, revealing both the crass, low-class stigmas attributed to musicians—still prevalent in early-twentieth century Iraqi Jewish society—as well the shifts in attitudes towards music-making (and associated class orientation) among the younger generation.

Yossef displayed exceptional musical talents from an early age. Due to the lack of music teachers, he became an autodidact. At the age of fourteen Zaarur began participating in performances by two exclusive chalgi ensembles of Jewish musicians (the Pataw and Bassoon ensembles) who entertained at weddings and other joyous occasions in Baghdad. This gave him the opportunity to mingle with professional musicians and to learn from their playing techniques. Although focused primarily on instrumental music, Zaarur could sing the vocal sections of the Iraqi Maqam, including the concluding pastat. He also listened to early commercial Egyptian recordings, among them those by the El-Akkad ensemble and its renowned qanun player Mohammed El-Akkad al-Kabbir (1850-1931). Al-Kabbir was the grandfather of the no-less-renowned qanun master Mohammed Yousri Mustafa al-Akkad al-Saghir (1911-1993), with whom Zaarur maintained a professional relationship, most especially after the two had met at the 1932 Congress of Arabic Music in Cairo (see more below). Al-Akkad al-Saghir was married to the Jewish singer Suad Zaki and the couple spent parts of their lives in the United States and later on in Israel.

In comparison with other Arab countries, the qanun entered Iraqi music at a relatively late stage. Besides Yusuf Zaarur al-Kabbir, only two other Jewish musicians played qanun professionally before Yossef Zaarur, Azuri Abu Shaul and Sion Ibrahim Cohen (Sayoun al-Qanundji, 1895-1964). These musicians played mostly in coffee houses in the early twentieth century. By 1925, the instrument had become integrated into ensembles featured on the first commercial recordings conducted in Baghdad, by the Baidaphon label.

Zaarur purchased his first qanun around 1918, acquiring command of this complex instrument in part by listening to commercial recordings that became available in Baghdad after World war I. Besides the qanun, Zaarur learned to play other instruments including the nay (Arab flute), violin, and cello. Family lore has it that at twenty years of age Zaarur even opened a music school, where he taught a variety of instruments. According to his daughter’s research (interview at 5:20), even the celebrated brothers Daoud and Salah al-Kuweiti studied at Zaarur’s school when they were still children. However, there is no other documentation or evidence that Zaarur headed such a school, at least not as a formal operation. Moreover, we know that the Al-Kuweiti brothers were not permanently settled in Baghdad until 1930 (Dori 2022: 95), by which time they were highly accomplished professional musicians. According to Kojaman (2001: 59), the first private music school in Baghdad was established by a certain Yusif Habib, an immigrant from Aleppo. Kojaman actually quotes Saleh al-Kuweiti’s statement that Habib’s school was established only in 1928.

Contribution to Iraqi Music

By the age of eighteen (c. 1920), Zaarur’s virtuosity, extensive knowledge of the Iraqi maqam repertoire and absolute pitch had rendered him known as a master musician in Baghdad. He enhanced the role of the qanun in Iraqi maqam music at a historical moment that coincided with the shift of many Baghdadi musicians to the aesthetics of modern Egyptian music. By this time the qanun had become a leading solo instrument rather than solely one used to accompany singers or other instruments and Zaarur helped pioneer this process. His versatile repertoire extended across various Middle Eastern musical genres, from the Iraqi maqam to Egyptian tarab music, alongside various Persian, Kurdish, and Turkish musics. Zaarur was also a prolific composer. He composed songs in diverse genres including the Egyptian taqtuqa; modern Iraqi songs similar to those by Saleh al-Kuwaity; muqadimat (instrumental versions of vocal sections of the Iraqi maqam); pastat for the conclusion of Iraqi maqam performances as well as instrumental dawalib (sing. dulab, introductions to songs; Dori 2022:197-8). One of his vocal compositions, ‘Ya najmat ebilel’ ( يا نجمة ال بالليل تزهي ) was recorded by the distinguished Jewish singer Sultana Yusuf (1910-1995) for His Master’s Voice in 1936, attained the status of an Iraqi folksong. His compositions contributed to the promotion of the Iraqi maqam in Iraq and beyond.

Zaarur collaborated with the best Iraqi maqam singers of his time, among them Rashid al-Qundarji, Najm al-Shaykhli, Salman Moshe, Rubin Rajwan and Yusef Horesh. His international career also took him to Egypt, Lebanon, Syria and Turkey. In 1937, while in Syria and Lebanon, he recorded with the al-Kuweiti brothers and singer Salima Mourad for the Syrian Sodwa label.

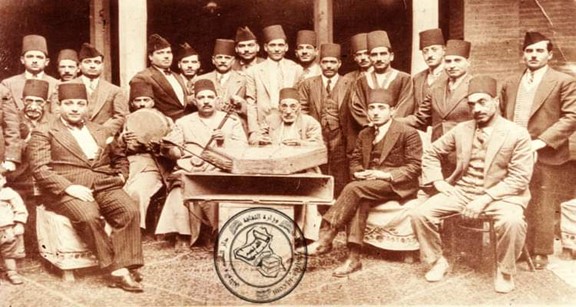

In 1931, Zaarur participated in a prominent performance in Baghdad organized by the famous Egyptian violinist (of Syrian origin) Sami al-Shawwa (1889–1965), in support of a music teachers' seminar in Baghdad. Between 1932 and 1934, Sami al-Shawwa made additional visits to Iraq, where he toured around the country and recorded sessions with the most renowned singers for different labels, including His Master’s Voice (HMV) and Odeon Records. For these recordings, al-Shawwa selected Zaarur as qanun player and Azuri Harun al-Awwad (Ezra Aharon) as oud player.

Sami Al-Shawwa's visit, Baghdad, November 1930.

Seated and standing, left to right: Al-Shawwa, Ibrahim Salah, Hugi Patwo, Nahum Yona, Shaul Zangi, Al-Shawwa’s companion, Meir Zaarur, Yossef Zaarur, Ezra Aharon Azuri, Daud al-Kuweiti, and other unknown Iraqi musicians.

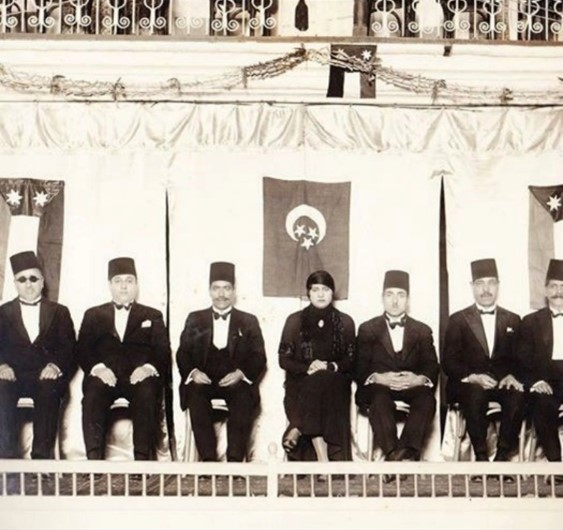

Sami Al-Shawwa's visit to Baghdad in 1931, performance at Cinema Royal Baghdad.

(Zaarur on qanun and Azuri on 'ud)

Sami Al-Shawwa's visit, Baghdad, 1931.

Seated and standing, left to right: Al-Shawwa, Ibrahim Salah (daf), Ephraim Kaduri Basun (santur), Al-Shawa’s companion, unidentified Iraqi drummer, Ezra Aharon Azuri, Yossef Zaarur, an unidentified Iraqi musician.

During these same years, Zaarur met the rising stars of the Egyptian song, Mohammed Abdel Wahab and Umm Kulthum, during their appearances in Baghdad. Umm Kulthum visited Iraq for the first time during October-November 1932, accompanied by her orchestra. She was invited by producer Meir Zaarur, Yossef Zaarur’s cousin, an artists’ agent who lived in Cairo and maintained connections with distinguished musicians in Egypt’s capital. Lacking prior experience with Meir Zaarur, Umm Kulthum sent a letter to an Iraqi friend, asking whether she could trust him (see below). After establishing a positive relationship with the agent, Umm Kulthum gave eight performances, which began on October 18, 1932, at the al-Hilal Theater located on the fashionable Al-Rashid Street in Baghdad, where she was welcomed by large crowds of Iraqis. During her visit she frequented Yossef and Meir Zaarur’s residences and sang with them privately (as did Abdel Wahab during his subsequent tours in Iraq). Following Umm Kulthum’s visit, many coffee houses in Baghdad were named after her. She returned to Baghdad in 1946 at the invitation of the Regent Prince Abdullah. By this time, Zaarur was the head of the Music Department of Radio Baghdad (see below) and he invited Umm Kulthum to perform at the station.

Umm Kulthum performing with her orchestra in Baghdad, 1932.

Meir Zaarur (second from right) with Umm Kulthum in Baghdad, 1932 (Shaul Zangi is fourth from left).

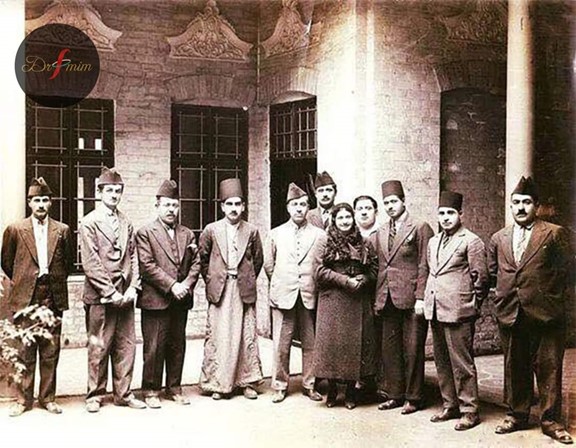

Zaarur also participated as a prominent member of the ensemble that represented Iraq at the Congress of Arabic Music that convened in Cairo, Egypt, between March 13 and April 3, 1932. This ensemble, comprised of Iraqi Jewish musicians, accompanied the aforementioned distinguished Muslim singer Muhammad al-Qubbanji. Zaarur was undoubtedly one of the leading figures of the ensemble, although diverse accounts also attribute the leadership of the Iraqi delegation either to the ‘ud player Ezra Aharon or to al-Qubbanji. The ensemble achieved remarkable success at the Congress, being recognized publicly by the King of Egypt himself with a special mention (Hassan 1992: 136-7). Several testimonies mention that during the Congress prizes were awarded to either the Iraqi ensemble as a whole or to some of its individual musicians. However, there is no solid evidence that such prizes were in fact given. During the Congress, Zaarur recorded with the Iraqi ensemble, as well as two additional solo taqasim.

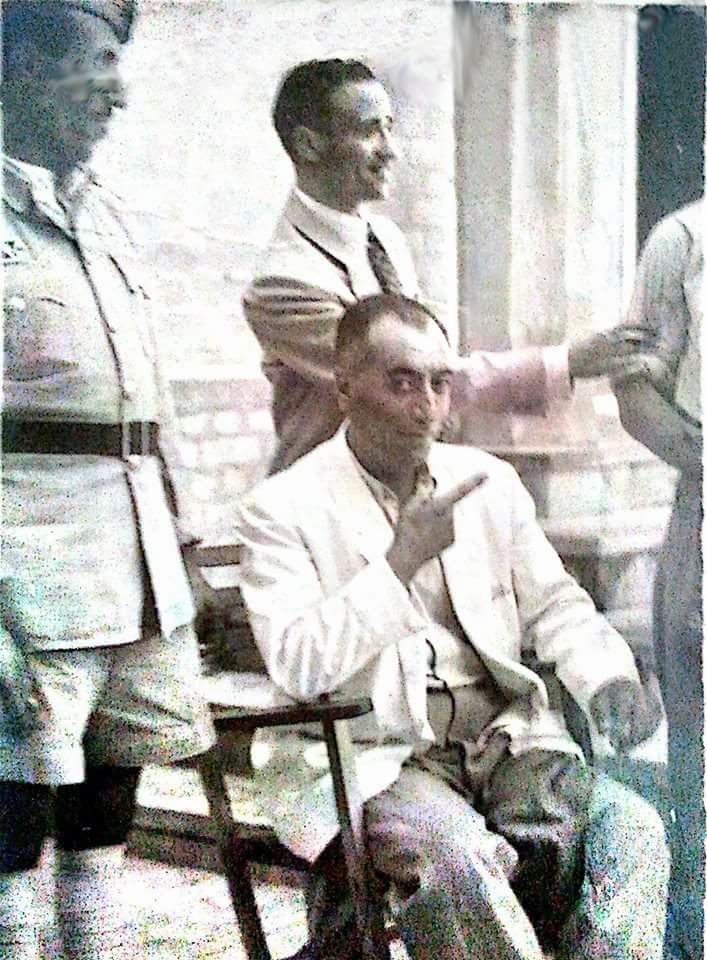

Cairo Congress, 1932. Recording session by H.M.V. (Zaarur, third from the right).

Cairo Congress, 1932.

Yossef Zaarur seated second from right, next to him (third from left) is the singer Muhammad al-Qubbanji.

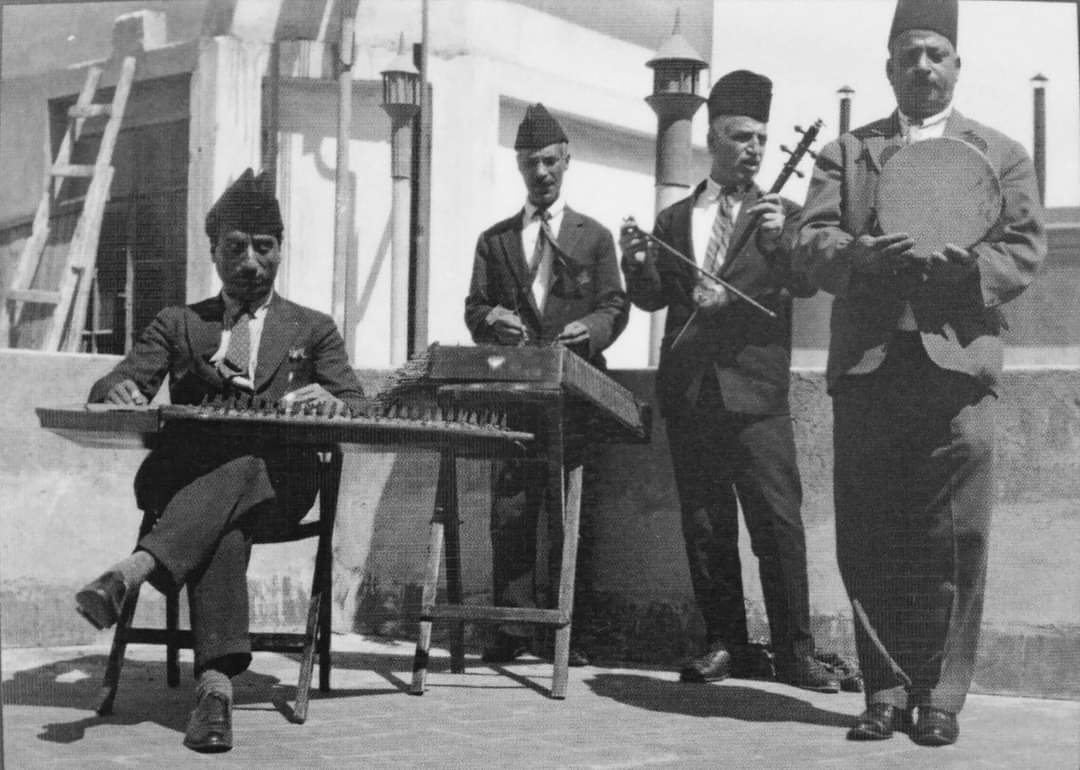

Cairo Congress, 1932, rooftop of the Cairo Academy of Music and Arts.

Members of the Iraqi ensemble (right to left): Ibrahim Salah, Salih Shemayil, Yossef Patwo, Yossef Zaarur.

Director of Radio Baghdad’s Music Department

Radio Baghdad, aka Republic of Iraq Radio, launched its first broadcast on July 1, 1936 Soon after, the new radio station established its first orchestra, led by Yossef Zaarur. The historical photo of the ensemble, taken during one of the first broadcasts of 1936 features Daoud al-Kuwaiti (oud), Yusuf Zaarur (qanun), Hussayn Abdullah (percussion), Yakub al-Imari (nay), Saleh al-Kuwaiti (violin) and Abraham Qazza (cello). Following the firing of the al-Kuwaiti brothers from the radio in 1941—either due to their refusal to perform on Jewish holidays (Dori 2022: 145) or possibly, because of improper moral behavior (oral communication of Albert Elias to David Regev Zaarur)—Zaarur was appointed, apparently with the backing of Prime Minister Nuri al-Said, as head of the Music Department of Radio Baghdad. Zaarur held this position until he left Iraq and lost his citizenship on May 3, 1951 (see below a recorded interview with violinist Elias Zbeda). According to various oral testimonies by Elias Zbeda, Zaarur was also came to be in charge of the radio programming and his salary was doubled. Despite the dismissal of the al-Kuweiti brothers, Zaarur continued to invite them as guest artists in his programming. In order to avoid the authorities’ critiques, Zaarur also established an ensemble that consisted solely of Muslim and Christian musicians who performed on Sabbaths and Jewish holidays, when their Jewish counterparts were not available. According to Zaarur’s daughter (interview at 7:04), he was even put in charge of selecting the Quran readers who appeared on Radio Baghdad.

Iraqi Broadcasting Authority Orchestra, 1936.

Seated and standing, from left to right: Daoud al-Kuwaiti, Yusuf Zaarur, Hussein Abdullah, Yakub al-Imari, Saleh al-Kuwaiti and Abraham Qazza.

Iraqi Broadcasting Authority Orchestra, 1938

Seated and standing, from left to right: Hussein Abdullah, Yusuf Zaarur, Muhammad al-Qubbanji, Daud al-Kuwaiti, Abraham Qazza, Salah al-Kuwaiti, Yakub al-Imari.

Having wholly devoted himself to the Baghdad radio station, Zaarur rarely performed, except for the exclusive audiences of King Ghazi (and, after his premature death in 1939, for the Regent Prince Abdullah’s audiences), government ministers and the mayor of Baghdad. After 1948, in his capacity as head of the radio’s music department, he initiated three studio ensembles that specialized in Iraqi maqam and rural folk music respectively; Kurdish music (directed by Jamil Bashir), and Egyptian music and muwashshahat (directed by Rawhi al-Khamash who had just arrived in Baghdad as a Palestinian refugee during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war; see Dori 2022:198). Zaarur trained numerous musicians and singers for these ensembles and integrated them into various radio programs he also produced. According to Elias Zbeda (b. 1931)—a talented young Jewish violinist who played alongside Zaarur in Radio Baghdad—Zaarur also endeavored to include young Jewish singers and musicians on the radio, such as Albert Elias, Abraham David Hacohen, Abraham Salman, Daud Akram, Sasson Abdo, Yosef Yaakov Shem Tov, Salah al-Shibli and the aforementioned Elias Zbeda, among others. Beyond salary and status, employment in the radio also protected one from being recruited to the Iraqi army. Albert Elias (in a personal communication to David Regev Zaarur) recounted that his mother asked Zaarur personally to integrate her son, who was just seventeen years old at the time, at the radio, so he could avoid the draft.

Zaarur also facilitated the distinguished Iraqi singer Nazem al-Ghazali’s (1921-1963) rise to prominence. He signed al-Ghazali to the radio in 1947. While al-Ghazali introduced himself as a performer of Egyptian songs, after auditioning him Zaarur offered to instruct him in the Iraqi maqam. According to family lore (see interview with Zaarur’s daughter at 00:15), and testimonies by Albert Elias and Elias Zbeda, al-Ghazali would visit Zaarur at his home three times a week to learn how to perform the Iraqi Maqam in true Iraqi fashion, and Zaarur even composed several Iraqi songs for him (Moreh 2016). This emphasis on al-Ghazali’s relation of dependence on Zaarur, as a singer who eventually became one of Iraq’s most beloved modern singers, reinforces the late re-memorialization of the vital role Jews played in shaping the modern Iraqi musical culture. Not surprisingly, al-Ghazali married the great Iraqi-Jewish singer Salima Pasha Mourad—a diva Zaarur had accompanied and composed songs for in the 1930s, among them ‘Haya lawasl mar’ and ‘Ya walad nakkis al fina.’ Salima Mourad eventually converted to Islam in order to marry al-Ghazali.

Courtyard of the Iraqi Broadcasting Station, Baghdad, 1948.

Left to right: The commander of the Baghdad police, Yossef Zaarur, Sasson Abdu (violinist), Hashim al-Rajab (santur, maqam singer).

Yossef Zaarur at the Iraqi Broadcasting Station, Baghdad, 1951, as Music Department Director.

Zaarur and the Iraqi Jewish Community

Zaarur contributed to the Jewish community in Iraq both musically and in socio-economic domains. As a director at the radio station, he cultivated relationships with influential figures in the Iraqi government, utilizing these connections to assist numerous Jewish artists in times of need, as well as poor Jewish families and brides who could not afford a dowry.

A family anecdote exemplifies Zaarur’s intimate relationships with the authorities during the 1940s. On June 1-2, 1941, during the events of al-Farhūd, or “violent dispossession,” Jews and Jewish property were targeted by an incited mob. While the riots were raging, and a strict curfew was announced, Zaarur was locked in the offices of Radio Baghdad and could not return to his family and community. Arshad al-Umari, the then powerful Lord Mayor of Baghdad (he later served as Prime Minister of Iraq for two tenures) sent a fire fighters’ truck that could freely circulate in the city to rescue the prominent Jewish musician whom he greatly admired. Zaarur eventually reached the Alliance School building and assisted in protecting the Jews who found shelter there (interview with Zaarur’s daughter at 1:33).

In 1944 Zaarur visited Palestine, then under the British Mandate, where he performed at several charity fundraisers (Moreh 2016). The main reason of his visit, as many members of the family assert, was to visit the grave of his father, who had come to Jerusalem in the late 1930s for medical treatment which he didn’t survive; Meir Zaarur was buried at the Mount of Olives cemetery. During Yossef Zaarur’s stay, he also visited the tomb of Rabbi Simeon bar Yochai in Meron (Upper Galilee), a pilgrimage site of great importance for observant Jews. These were critically tense time in Palestine, and hence a remarkable venture for a Jew carrying such a prominent position in the Iraqi mass media.

Towards 1948, as the conflict in Palestine became more acute, the geopolitical map in Iraq became more hostile towards Jews. Because of his prominent position in the Iraqi musical establishment, Zaarur’s Jewishness became a source of tension and he was boycotted. Between 1945/6, British representatives asked Zaarur to record (for additional payment) a series of solo pieces based on the Iraqi Maqam on reel-to-reel tapes. According to the family’s testimony, they asked him to meet them at the radio station in Baghdad in the morning—an unusual time because it was known that he began his workday in the afternoon. These recordings were taken to London and were heard in the BBC station for the Middle East programs, reaching the Arab world, Israel/Palestine included of course. In 1956 however, following the outbreak of the Sinai War, the BBC stopped broadcasting Zaarur's recordings, because by then he had become an Israeli citizen. They did so because playing Zaarur’s recordings could have alienated the Arab audiences of the British radio station.

Immigration to Israel

In May 1951, Zaarur left Baghdad for Israel with the rest of the Iraqi Jewry, leaving behind all his possessions as well as an illustrious artistic and managerial career. His wife Naima Abdo, whom he married in 1932, and their six children (five daughters and a son) accompanied him. Upon arrival, the family resided at the “Sha'ar Ha-aliyah” transit camp (near Haifa). They later relocated to Pardes Hanna, and eventually settled in Ramat Gan, alongside other Iraqi-Jewish immigrants who formed a prominent community there.

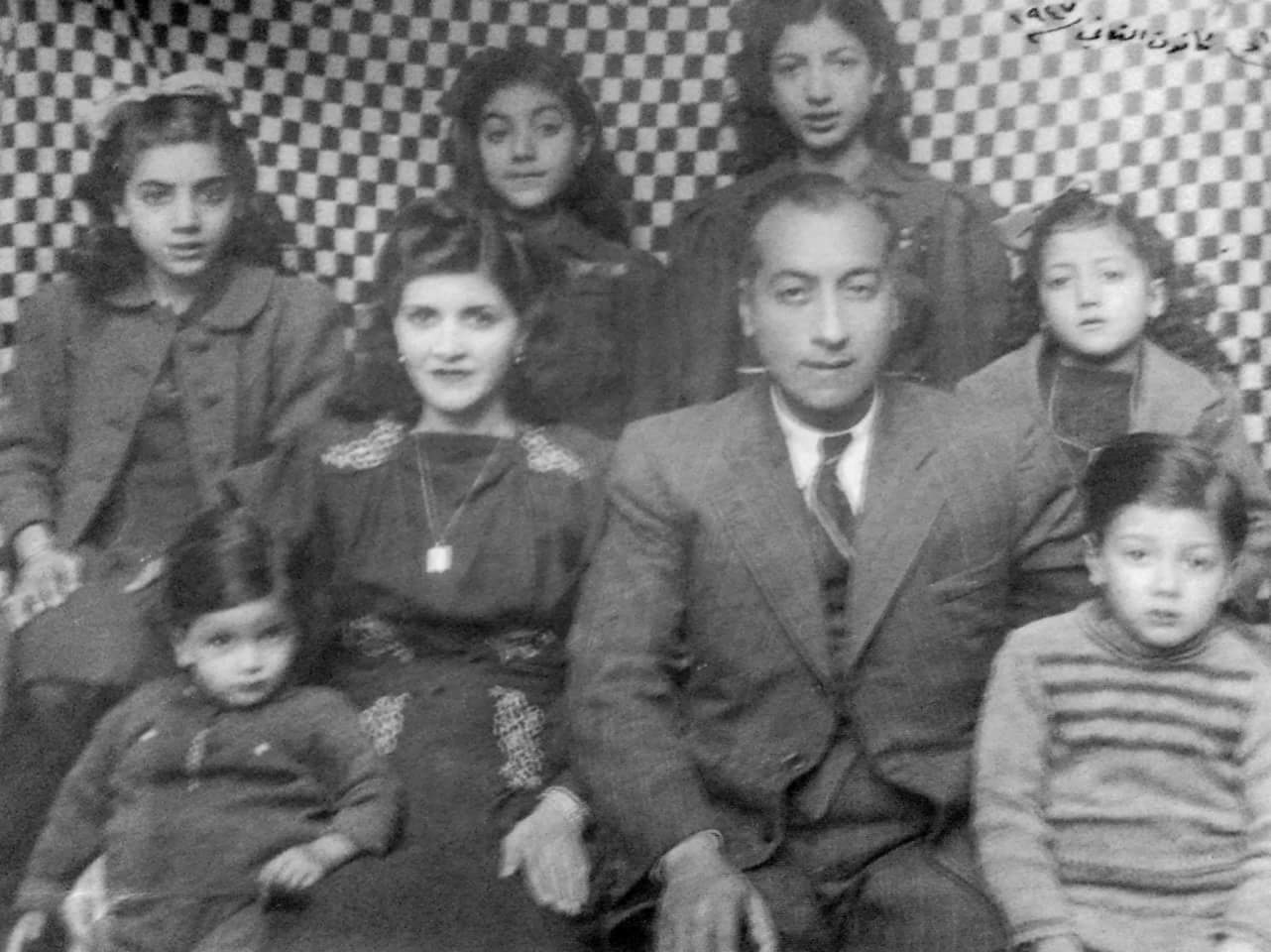

Engagement celebration of Yossef Zaarur and his future wife Naima Abdo, 1932, Baghdad.

Yossef Zaarur with his wife and six children, 1947.

In Israel Zaarur continued to perform, although intermittently, at private gatherings within the Iraqi Jewish community, in order to provide for his family. As the Israeli radio’s Voice of Israel in Arabic department expanded, Zaarur often guested on its music programs—showcasing his talent through solo performances and guest appearances—but he never became a permanent member. He eventually established a small informal Iraqi maqam ensemble properly named “Chalgi Baghdad,” which was programmed within radio’s Arabic Music department’s broadcasts. This ensemble featured the Iraqi maqam singer Heskel Qassab, who Zaarur worked with regularly (Kojaman 2001: 53-4). Qassab and Zaarur died on the same year, and according to some, on the very same day. Recordings of this ensemble are accessible through the website of Israel National Library Sound Archive and well as online. See for example their late recording of Maqam Hijaz Shaytani and of the most famous pasta Fog el-Nakhal, joined by violinist Sasson Abdo.

During his career in Israel, Zaarur also met with renowned Western classical musicians, among them Leonard Bernstein and Yehudi Menuhin, who became Zaarur’s admirer and also played with him (Moreh 2016). Zaarur also contributed to the preservation of Iraqi music in Israel by transmitting his knowledge to a new generation of musicians, some of whom have already worked with him in Radio Baghdad in the late 1940s—among them the qanun player Abraham Salman, the violinist Sasson Abdo, the nay player Albert Elias and others. This selected group of artists became the backbone of the Israeli Broadcast Authority (IBA)’s Arab Music Orchestra, featured on the Voice of Israel in Arabic.

Yossef Zaarur at his grandson Roni’s 4th birthday, 1963.

Right to left: Zaarur, grandson Roni, granddaughter Nurit, Avraham Basun (violin), Haskel Katzav (drum, vocals).

Yossef Zaarur, 1966

Yossef Zaarur died in 1969 leaving behind a rich musical legacy. As one of the most eminent qanun players of his time in his homeland and beyond, he was a pivotal figure in the history of the Iraqi maqam, modern Iraqi music and Arab music more generally.

See also in our website the project on Music, Muslims and Jews.