The passing of the founder of the Yiddish theater spawned a touching emotional response by Idelsohn. In grieving Goldfaden, Idelsohn projected into this text his own vision of Jewish history and destiny as well as his take on prophecy and genius. This is one of the earliest Hebrew writings published by Idelsohn (February 7, 1908) after he settled in Jerusalem.

Source Text

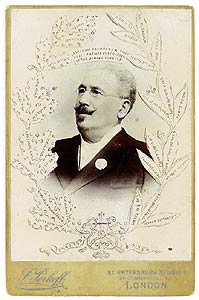

Abraham Goldfaden

By Abraham Z. Ben Yehuda [Idelsohn]

Hashkafa, February 7, 1908, p. 1-2

Translated and Annotated, with a Commentary by James Loeffler, Edwin Seroussi and Yonatan Turgeman

A sad rumor arrived that the founder of the Jewish theater in Yiddish, Abraham Goldfaden has died.

And while all Jewish newspapers and even some non-Jewish newspapers reported, after the disappearance of the deceased, the events of his life, however according to convention only in a superficial manner --- here he was born, here he lived and here he died and the like, there is in my opinion room to talk about such a person beyond the ordinary, and to ponder a bit about his personality.

Goldfaden was, as mentioned, the founder of the Jewish theatre in the language of exile [galut]. Now, after thirty years [since its foundation], it is easy for a Jew to utter this word ---theatre--- from his mouth as if natural to him, and even to a Jerusalemite! However, back then, a whole generation back, the meaning of this word was unknown, not only to Jerusalem Jews, but also to Jews in Russia and Romania, and to all the children of the diaspora [bnei ha-galut] in the Middle East. Back then it was hard to understand why this thing had been invented; because, beyond the stories of Purim and the entertainment of the Purimshpils that were only [intended] to amuse the masses on a day in which they were commanded to cheer up and to drink, even though drinking causes drunkenness as it is known… However, except for this great day, the Jew sat down in mourning, in humiliation and in distress, and his soul was sad. All days of the year he sits and bemoans the exile of the people and the exile of the Shekhinah, and what business does he have with rowdiness such as a [theatre] play [mishak]? On the other hand, there is another mystery[1] beyond the simple meaning[2] of a [theatre] play. That is to say, there is another concept of theatre that the Jew in exile did not know. Because he never saw theatre other than the Purimshpil. Indeed, he did not know of it because there is a big difference between “[Purim] comedy” and “theatre”! And one does not look after appearances but [after] the essence [of theatre], that is its content; the same stage serves two purposes, a [play] of comedy and rowdiness, and [a play] whose content is serious. Important and elevated [content] that influences the course of a person’s spirit as a person! --Because the stage was not invented for comedy only but also for tragedy --- all this was unknown to the children of the diaspora. For this reason, they believed in what they saw and knew --[about] the superficial and the ludicrous in this thing [comedy], and for this reason they ordained that comedies that generate laxity are allowed only on the day of Purim.

All this was until Goldfaden.

And how did he come to create theatre? How did it occur to the son of the ghetto to create something that he knew only from rumors and had never himself seen? And how did he have the audacity to create a new thing, opposed to what was customary among the people?

This is a question that is hard to answer and what the author of the article in Ost und West who tried to find the real cause proposed, is, in my opinion, a failure.[3] Because whomever knows the nature of the [Jewish] people to ban all that is new and contrary to the accepted [norms], will recognize, that it was not the boredom of the businessmen and the money [available] then in Bucharest that led to the creation of “the play” where they could spend their [leisure] time, and also other issues -- but if Max Nordau was correct when he said that genius is called only the one who creates something new that never before existed,[4] and the creator makes the effort to publicize his creation to the world in spite of the obstacles, and that for this enterprise one can later on find the talents[5] who develop and expand this idea among the people until [the people] finally accepts it, and eventually it becomes accepted to the point that if someone [dares to] touch it immediately he is rebuked with bans and war -- if this sentence is correct, then we can claim that Goldfaden had all that! See for yourself: a son of the ghetto in his soul, daringly ventures to shatter the fences and introduces something new! -- At the beginning they laughed at him and called him the “play of Purim.” However, after a few days, when Goldfaden grew, they withdrew, and then they took the well-known step that each honorable person regretfully knows: they banned him and asked him to stop --- otherwise they would turn him in to the authorities…

This was indeed a “great defeat.” Because of this [episode] Goldfaden fell and did not recover. With the closing of his theatre in Odessa the source of his spirit was closed. His blessed spirit departed from him -- and he died. -- By saying died, I do not mean his recent death in New York, “that hundreds and thousands of Jews” went to paid him last honors, the real grace -- No! This real grace came too late because Goldfaden died a spiritual death already twenty years ago, on the day his theatre was closed.[6]

And you my dear readers, do not be surprised by that, [because] among us the Jews everything is possible. You can kill someone spiritually and leave his body [alive] like an artificial machine. And how many poets, wise visionaries and authors, appeared in our midst, who could have been a blessing to their people, but for whatever reason they died. Something killed their spirit forever -- while they, that is their bodies, remain alive and well, continuing to function.

And who knows [how] to tell the story of those bodies who are walking among us and we refer to them as if they lived in the previous generation; so and so wrote and sang and imagined already at the time when our fathers did not reach yet maturity; and now -- the so-and-so poet became a shopkeeper and the so-and-so author became a pimp, and the so-and-so scholar – became simply a schnorrer! And so on and so forth…

This is a sad spectacle among our people. Especially in the last generations, when almost no intellectual reached maturity, he failed to fulfill his spirit, he did not complete the mission he started, and [even] if he produced [something] ---- he did not [really] create it but he is arguably an animal, a dwarf!

And this is the judgement about the founder of the Jewish theatre, a creation of his spirit. How? Is he not a dwarf who raises a bitter laugh, degenerates, and flees [the stage]? And he is the one who gave birth to his people? They say: as fathers as sons, healthy fathers -- healthy sons, and this father who originates in the despicable and dreadful ghetto -- i.e. the Romanian ghetto, did not have childhood or education; did not read and did not study [Torah], did not experience anything of a natural healthy life.

Genius he was, but his spirit did not find a place to develop, as in the case of his compatriot, for example, “Mayer-beer.” And who knows, if Goldfaden had enjoyed the living conditions of his compatriot “Mayer-beer,” had he had rich parents who lived in Berlin, outside the ghetto, and enjoyed life as a person deserves, would he not become for us what “Mayer-beer” was? But returning to the question, would we then have had a Goldfaden? Wouldn’t he have followed the path of all those who betray their people?

In any case then, his works would have endured and be fully alive like those of a “Richard Wagner” or a “Verdi.”

Goldfaden had, in particular, the same talents as “Wagner” had; like him, he was also a poet who wrote his theatre plays and also designed melodies for them. And he presented it on the stage by himself. And he raised disciples in his spirit and style. However -- what a great difference -- as a person and his shadow.

And this is our national calamity. Because our lives are only a shadow of life, and for this reason our spirit is not healthy and strong. And those with our spirit are only shadows.

And the fate of Goldfaden was the same as that of all our “geniuses.” And he undoubtedly was a genius. This person is busy with ‘Hotzmakh,’ ‘Makhshefe,’ ‘Bakho yavke,’ the absurdities and the slime of the ghetto, and suddenly he envisions plays such as ‘Shulamis,’ ‘Bar Kochbe,’ and ‘Yemos ha-meshiech,’ as [Hebrew novelist] Abraham Mapu [1808-1867] at his time; this Mapu grew on the slime of the Jews’ street in Slobodke, and was busy with Kabbalah and demons, and suddenly --- ‘Ahavat tziyon,’ ‘Ashmat Shomron,’ true carnal love, Zion and Jerusalem of the lower world, and hills and valleys and the fragrance of the fields and the vineyards, and the songs of the real shepherd who longs for his beloved [not for the Shekhinah as it were…].

How did he reach there? -- How could the children of the ghetto, who never experienced nature, who never saw a person standing up proudly, whose veins are stiff and looks with penetrating eyes -- imagine heroes? That is to say, Jewish persons with real arms, with hands, and not only with voices, and most importantly, how did they come to the Land of Israel? -- Those who did not see the Bible in its real form and in its entirety. Beyond the passages and the fragmented verses that are quoted in the Talmud. And here they come, those who were called crazy and sinners, they remove the yokes of the past, that were sanctified for the angels of heaven, shake off from themselves their conventional shells and make them simple human beings, people like us?

And who is going to count the pearls taken from the people’s treasure, only those who witnessed the pleasant effect that Goldfaden had on the masses knows the extent to which his soul was taken from the soul of the people. The melodies of his aforementioned plays are an echo of the voice of the people’s heart. And in spite of this innovation that our fathers could not imagine, the people connected themselves to Goldfaden with love and affection. He was a genius, invented something new that did not exist before, however -- a Jew, a song of the same nation, whose life is not life, whose cheeks lack the pleasure of life, there is no splendor to life, no radiance in life. Life that lacks the most essential component -- nature!

A nation whose leaders are not landlords but are detached [from the land]. And I remember that once I met a well-known Jewish writer, Mr. Reuven Brainin,[7] who returned from the Congress in Basel to tell the praises of the people and its leaders, its geniuses, and while speaking he tossed from his mouth the name: Goldfaden,[8] and [said: “at first] I was taken aback thinking that perhaps he [Goldfaden] woke up and his spirit was awakened by the new national regeneration --- woke up and created a new play, a new “Yemos ha-mashiach”,[9] and staged it in front of the public --- the representatives of the Jewish people. [A play that shows] how are they going to live then after their hopes are fulfilled and that [the new play] will surely energize the spirit of the leaders and the delegates and they will renew themselves and strengthen their hopes and determination”.

“However, no! -- I met the foolish Goldfaden” --- so told me the wise man [Brainin] --- “I spoke with him for an hour and impressed me as a total ignoramus and dolt, who had not read a book in his whole life.”

“And what was he doing in the Congress,” I asked him.

“What was he doing? What the losers of this kind do --- and there are many like him in the Congress --- shnorern! [beggar] --- shnorern! shnorern!!--- these are your geniuses, Israel!”

And perhaps Zangwill was right when he said, “King of the Shnorers.”[10]

Because… alas, enough speaking!

Commentary

Idelsohn’s essay, partly an obituary of Abraham Goldfaden, partly an aggressive Zionist manifesto, is among his earliest publications in Jerusalem’s newspapers. Hashkafa, a weekly established by Eliezer Ben Yehuda in 1896, was one of the first Hebrew newspapers published in Ottoman Palestine. Idelsohn’s article appeared in one of the last issues of this periodical publication before it became the daily Ha-Zvi.

Goldfaden’s death provides Idelsohn a springboard to express his current state of mind. An ecstatic feeling of physical regeneration upon his immigration to the Land of Israel seems to animate his writing. Written in a convoluted modern Hebrew prose, Idelsohn uses new Hebrew words coined by his mentor and neighbor in Jerusalem, Eliezer Ben Yehuda. He shows an impressive familiarity with the modern Jewish bookshelf, mentioning in this short publicist essay the names of Max Nordau, Israel Zangwill, Reuven Brainin and Abraham Mapu, as well as with the relatively short history of the Yiddish theatre.

Contempt and admiration for Goldfaden dwell together in this article. Goldfaden is a genius, a path-breaking pioneer, but also a pathetic “son of the ghetto.” And “ghetto” is the leitmotif of this text, appearing no less than seven times in different contexts. The ghetto is a synonym of obscurantism, a walled refuge of the debased Jew, a locked chamber suffocating any access to the fresh air of civilization. Those Jews who were fortunate to have the opportunity to break away from the ghetto, such as the composer German composer of Jewish origin Giacomo Meyerbeer (whose name Idelsohn hyphenates to stress the composer’s Jewishness), betrayed their people. No sin is more shameful for Idelsohn (at this stage of his life) than the sin of assimilation.

The worship of nature, physical strength and the ownership of land are basic tenets of Jewish national renewal in Idelsohn’s eyes. These are images typical of the writing of Second ‘aliyah intellectuals, yet they will not persist in Idelsohn’s writings for long. In fact, Idelsohn’s relation to the settlers in the Galilee and Judea never seemed to have developed closely, as he remained devoted to the ideals of Hebrew cultural revival current among the bourgeois urban circles of Jerusalemite intellectuals.

In his summary, Idelsohn presents Goldfaden as a tragic figure, the victim of the geopolitical circumstances as well as of the conundrum of modern Jewish identity. The internal politics of the Russian Empire towards its Jewish population shuttered down cruelly Goldfaden’s vision of a modern Yiddish theatre. Goldfaden’s oeuvre itself reflects his inconsistency, oscillating between “light” (ideals of territorial Jewish nationalism staged theatrically) and “darkness” (dull entertaining for the ignorant masses of the diaspora). A hero of Jewish modernity who heroically broke the barriers of the ghetto, Goldfaden was condemned to wander from door to door asking for recognition and financial assistance. And recognition came too late for him, only in his multitudinous funeral.

Throughout his article, Idelsohn describes Goldfaden as ‘the founder of the Jewish theater [hizzayon] in Yiddish,’ thus siding with the (relatively) new interpretation of the term hizzayon = theater. However, the signification of the word is not stable. Towards the end of the article Idelsohn uses ‘hizzayon’ in the meaning of a ‘play’: ‘[Goldfaden] woke up and created a new play [hizzayon].’ This meaning of ‘hizzayon,’ which is no less theatrical, is highly documented and predates Ben Yehuda.[11] Idelsohn adds that Goldfaden, like Wagner, ‘was also the poet who wrote his theatre plays [hezzyonot] and also designed melodies for them. And he presented it on the stage by himself.’ In the same way, Idelsohn will later describe his own Gesamtkunstwerk, ‘Yiftah’, as ‘hizzayon negini’ (musical play).

Modern Hebrew writers embraced the biblical understanding of the poet as a prophet-seer and incorporated it into their non-religious Zionist agenda through the figure of ‘ha-tzofe le’beit Yisrael.’ Idelsohn, on the other hand, based his ideal of a modern Hebrew ‘prophet-seer’ not on the poet but on the cantor, ‘hazzan.’ In an article announcing the opening of the new ‘Institute for the Song of Yisrael’ (Makhon Shirat Yisrael) Idelsohn describes the main objective of this institute: to pave a way for the ‘Song of Israel’ to become a durable living practice. On the practical side, Idelsohn’s vision requires the creation of a special elite group of Hebrew singers. Each singer will be sent to his own country of origin outside Israel/Palestine and, building on his mastery of his specific heritage, will deliver a powerful performance of the “real” song of Israel that hopefully will awake the spirit of his exiled brothers and direct it towards Jerusalem.

Here we find the equation hazzan (cantor) = hozze (Prophet): ‘… the heart of the Jews will forget the usual concept of ‘cantor’ (hazzan) … and the cantor will acquire a new concept, the concept of a ‘prophet’ (hozze).’ [12] The theatrical realization of the cantor-prophet figure follows suit. The final task of Idelsohn’s institute is to stage ‘hezzyonot’ [theatrical plays, plural of ‘hizzayon’] of Israel’s history, with musical accompaniment (i.e., ‘hizzayon negini’), ‘that will show the people their “great past,” the character of their heroes and geniuses, how the nation’s fathers lived and act on this land, and these “hezzyonot” will capture the spirit of the people…’.

In his article on Goldfaden Idelsohn asks: ‘How did he [Goldfaden] come to create theatre [hizzayon]? How did it occur to the son of the ghetto to create something that he knew only from rumors and never saw?’ To Idelsohn’s answer—Goldfaden was a genius who partially transcended his time and place—we can now add another: Goldfaden was a ‘hozze,’ a visionary, a prophet. Though his own creation did not break off with the shadowy existence of Jewish life in exile, it awakened in the heart and mind of Jews a long-forgotten need for a prophetic display of their past, present and future. The genius stands above history, while the prophet inhabits his age, explaining the import of historical events, and reshaping their meaning in the process.[13] In this respect, Idelsohn projects something of his own self-understanding as a would-be prophet of Hebrew culture. According to Idelsohn, something sparked in the depths of Goldfaden’s murky vision, a secret (sod): the ability and desire of the Jewish heart to open itself to the all-embracing effect of a future opera in Hebrew, i.e., the possibility and necessity of ‘hizzayon negini’. Looking back and recounting Goldfaden’s ‘hizzayon,’ Idelsohn captured his own visions – both fantasies and fears – of his own future.

End Notes

[1] He uses the word sod, hinting to the kabbalistic interpretation of scripture.

[2] Pshat, i.e. the literal meaning of scripture. All underlays are in the original.

[3] Idelsohn is most probably referring to the programmatic article by Fabius Schach, ‘Der Juedische Theater, sein Wesen und sein Geschichte,’ Ost und West 1, no. 5 (May 1901), cols. 347-358.

[4] Idelsohn is obviously hinting to Nordau’s famous essay Degeneration that deals with the psychopathology of the genius. It was originally published as Max Nordau, Entartung. Berlin: C. Duncker, 1892.

[5] Idelsohn uses this new Hebrew word kishronot for talent and adds “talent” in Hebrew characters in parenthesis.

[6] Idelsohn is referring to the ban on Yiddish theatre in the Russian Empire issued by Tsar Alexander III on August 17, 1883, that caused the collapse of Goldfaden’s career as impresario. On the ban see, John D. Klier, “‘Exit, Pursued by a Bear’: Russian Administrators and the Ban on Yiddish Theatre in Imperial Russia,” Yiddish Theatre: New Approaches, ed. Joel Berkowitz. Oxford: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2003, 159–174.

[7] Reuben ben Mordecai Brainin (March 16, 1862 – November 30, 1939) was a Russian Jewish publicist, biographer and literary critic.

[8] Idelsohn’s memory failed him, for Goldfaden attended the 1900 World Zionist Congress in London, not the first one in Basel. According to the YIVO Archive biographical note, at the Congress in London Goldfaden “was warmly welcomed. In the same year, the Yiddish world celebrated his 60th birthday. This included many warmly-written newspaper articles by the likes of Nahum Sokolow, Reuben Asher Braudes, Reuben Brainin, and others, as well as a great celebration in London, where a fund was established to support him and his wife for a year.” (https://archives.cjh.org/repositories/7/resources/3593) According to scholar Alyssa Quint, Goldfaden represented a breakaway Zionist group named Bekhorei Tziyon and used the opportunity of the London conference to raise money for himself and get access to the British Jewish high society. This evidence supports Idelsohn’s report of his meeting with Brainin. Alyssa Quint, The Rise of the Modern Yiddish Theater: Avrom Goldfaden and the Jewish Stage. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019, p. 190 and n. 51.

[9] Referring to Goldfaden’s operetta Meshiekh’s tsaytn (Messiah’s Time) from 1893.

[10] The King of Schnorrers - Grotesques and Fantasies (1893) is a novel by the British Jewish author Israel Zangwill.

[11] See the use of the term “batei hizzayon ha-tugah” (troyerspiel) in Yacov Taprover, ‘Musar haskel,’ Hamelitz, 20.6.1871, p. 174.

[12] ‘Makhon Shirat Yisrael bi-Yerushala’im,’ ha-Herut, 25.5.1910, p. 4.

[13] On the concept of genius in modern Jewish culture, see Eliyahu Stern, The Genius: Elijah of Vilna and the Making of Modern Judaism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.