Ethnomusicologist Avigdor Herzog was one of the founders of modern Jewish music research and documentation in Israel. His activities in the field of Jewish music were numerous and span for over eight decades in his capacity as performing musician, educator, collector, curator and ba'al tefillah. He was mostly known in Israel as the head curator of the Sound Archives of the Jewish National and University Library, today the National Library of Israel, an institution he directed from its inception in 1963 until his retirement. Yet, Herzog was much more than a curator. The following lines draw from my personal acquaintance with Avigdor as well as from documentary materials included in the edited volume honoring him, Lev shome’a (A Hearing Heart: Jubilee Volume in Honor of Avigdor Herzog = Dukhan vol. 16 [Jerusalem, Renanot, 2005]) and various interviews with him located at the Sound Archives of the National Library of Israel, especially the detailed ones carried out by the late Dr. Efraim Yaacov.

Avigdor Herzog at work in the Sound Archives of the Jewish National and University Library

The strong antisemitic atmosphere that reigned in Hungary between the World Wars and the experience of surviving the Holocaust left a deep imprint in Herzog’s life. By late 1949, unable to find a place for himself in the post-war Hungarian society, he fulfilled his dream and settled in the recently established State of Israel. Shortly after his arrival, Avigdor was already integrated into the fabric of the new society. His ties to the national religious movement and his musical and musicological upbringing soon opened doors of the young Israeli educational system, such as a teaching position at the seminar of religious youth leaders in Bayit Vagan (Jerusalem). There Herzog met Dr. Jonah Ben Sasson who eventually was appointed head of the Department of Religious Culture (Tarbut Toranit) of the Ministry of Education and Culture. In his new position Ben Sasson engaged Herzog in the founding of an Institute for Religious Music in 1955. Avigdor accepted this invitation on the condition that a tape recorder, then a rarity in the young Israeli musicological scene, be purchased to carry out field recordings.

Herzog in his youth in Hungary

Eventually called Renanot – The Institute of Jewish Music, the goal of this new institution was to document Jewish musical traditions and make them available to the educational system through publications. Herzog had now at his disposal the technological infrastructure and means of archiving that allowed him to immerse himself into translating the Hungarian musical vision of Bartok and Kodaly to the emerging Jewish society in Israel, a dream for the Jewish people that he had already envisioned even prior to his immigration to Israel. Already in 1958 he carried out a relatively long-term field expedition to moshav Berachia in southern Israel where he recorded new immigrants from the Island of Djerba (Tunisia), a community that became a focus of his interest because he believed in the antiquity on its musical lore. At the Institute Herzog engaged not only in recording but also initiated public activities, the most important one being the conference on Jewish music held each year during Hannukah, an event that takes place until the present. In addition, he produced various music publications as well as the yearbook Dukhan (“Pulpit”) that included the lectures read at each yearly conference.

Avigdor’s prolific ethnographic work during those early years became a cornerstone for the newly created Sound Archives of the Jewish National and University Library (today the National Library of Israel) that opened its doors in a process that started in 1963 under the initiative of Prof. Israel Adler. By 1965 the archive became functional. Now under the umbrella of the most prestigious institution of higher learning in the country in those days, Herzog intensified his ethnographic work as well as dedicated himself to the expansion of the collection with the private estates of scholars who recorded during the British Mandate in Palestine and the early years of Israel, such as Robert Lachmann, Johanna Spector, and Leo Levi. Later on the collection of Edith Gerson Kiwi was also incorporated into the archive. A modern recording studio was established with the best available equipment of the time, making possible recordings of the highest quality under the best conditions under the supervision of a professional sound technician. This new setting liberated the scholar from operating the equipment and allowed him to dedicate his full attention to the interviewee. The newly established Jewish Music Research Centre at the Hebrew University, expanded the trained personnel engaged in ethnography that enriched the Sound Archive during Herzog's tenure.

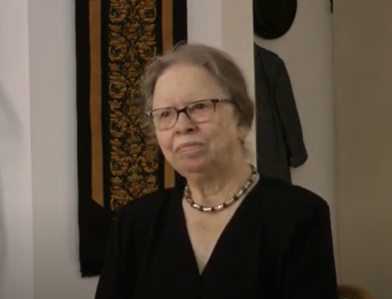

Avigdor Herzog on his retirement days

It is hard to summarize Herzog’s contribution to the preservation of Jewish and Samaritan musical traditions. Samaritan liturgy was a special subject of his interest and he entertained the possibility of completing a doctoral dissertation on this subject at the University of Illinois under Bruno Nettl. While this project was never completed, Herzog was and remained one of the experts on Samaritan music. Among the highlights of his ethnography, one can mention the recording of the entire liturgical cycle of the Spanish-Portuguese synagogue from London with the Reverend Eliezer Abinun (1912-1998) and the Southern German liturgical tradition from Cantor Avigdor Unna (1904-1982). In addition, Avigdor was himself an important carrier of the Hungarian Ashkenazi liturgical tradition and therefore he documented himself and was documented by others. Conscious that the Sound Archive should serve as a repository also for the musical traditions of Israel’s minorities, the team of which Herzog was a member initiated recordings of different Christian musical traditions of the Holy Land.

Another special interest for Herzog was the Ashkenazi repertoire of zemiroth Shabbat (Sabbath table songs; for an example see here), which he recorded and transcribed assiduously. However, this collection was never completed, the reason being Avigdor’s perfectionism, his belief that Western musical notation could describe oral renditions of vocal music to their utmost details, an approach that led to a dead-end. The consequences of this methodological impasse can be seen in Avigdor Herzog’s estate at the National Library of Israel (MUS 100) that includes numerous unedited musical transcriptions of oral traditions carried out by him over half a century.

He passed away on December 9, 2022, a few months after his 100th birthday.

For additional information in Hebrew, see the National Library of Israel blog.