Lukin, Michael. "Tish-nigunim Ascribed to Yosl Tolner and the Aesthetics of the Genre." Yuval, vol. XIII (2024).

Tish-nigunim Ascribed to Yosl Tolner and the Aesthetics of the Genre

Abstract

The tish-nigunim attributed to Yosl Tolner offer a glimpse into a genre without parallel in central-eastern Europe, as well as insight into the figure of a traditional Hasidic composer. A multiplicity of associations emerges as a defining typological feature, fundamentally shaping the aesthetics and semiotics of the tish-nigunim repertoire. Through an analysis of formal structures, rhythms, scales, motifs, melodic contours, and performance contexts, this study examines the interplay of male and female traditional creativity, perceptions of conservatism and innovation, notions of temporality, and attitudes toward local identities and transnational networks. An analysis of nigunim attributed to composers like Tolner reveals that, while acknowledging aesthetic norms shared with modern European repertoires, these composers saw their role in a distinctly premodern way: as uncovering the aesthetic potential of their musical tradition, rather than focusing on personal artistic self-expression.

Tish-nigunim in the Post-vernacular Era

This study aims to trace the unique characteristics of a type of music unparalleled in the central-eastern European landscape: Hasidic tish-nigunim. Nigunim (Yiddish nign, from the Hebrew niggun—melody) are chants, some with words but most without, historically performed primarily by men, either solo or collectively, in a monophonic texture. They serve various religious functions and have a mystical background. This genre apparently crystallized in the territories of Podolia and Volhynia during the eighteenth century, at a time when the Hasidic movement was forming in those areas of Ukraine (then part of Poland and later the Russian Empire). By the nineteenth century, it had become a widespread and significant genre; during the twentieth century many hundreds of Hasidic nigunim from various areas were notated and audio-recorded.[1] Tish-nigunim (Yiddish: table-melodies) comprise one of the most significant elements of the nigunim repertoire. Walter Zev Feldman (Feldman 2016, 49) stresses the significance of the distinction between this sub-genre and nigunim of other types. In his edition of Vinaver’s 1930s collection, Eliyahu Schleifer defines tish-nigunim as tunes “usually sung during festive or memorial meals at the Rebbe’s table. The melody is usually long and contains three or four sections, some in slow, others in fast tempo” (Vinaver 1985, 191). André Hajdu and Yaakov Mazor (2007, 429) emphasize that tish-nigunim made up “the core of the Hasidic repertoire.”

Although the dominant function of this music was not aesthetic contemplation but rather the expression and accompaniment of mystical experiences, it was widely appreciated for its beauty, musical features, and spiritual power, emerging from structural, melodic, and rhythmic qualities. These two functions—the extramusical as the primary and the aesthetic as the secondary—have received unequal attention. While the central role of nigunim in Hasidic ritual and thought has been extensively explored, few studies have delved deeply into the musical characteristics that underpin aesthetic appreciation within the pre-Holocaust tradition.[2]

Consequently, the correspondence between the expressions of the mystical and aesthetical functions—between the extramusical meanings and their musical representation—has not been sufficiently explored.

Yaakov Mazor and Edwin Seroussi (1990, 131) quote one of the first prominent Hasidic leaders, Yankev-Yoysef of Polonnoye (in his book Ketonet passim 15 col. 3), who distinguishes between three types of nigunim “according to their purpose”: “kavanah (devotional intention), yihud (unification), and lashir be’alma lehitpa’er (to sing for the sake of an individual’s expression without any specific ritual or spiritual connotation).” While this distinction is notable, no further research has examined the musical features that characterize each of the three. Another example, one that illustrates the other extreme of this lacuna, is the detailed description of musical modes, scales, and melodic patterns of nigunim from Galician traditions brought by Uri Sharvit (1995, xii–xxx) with no attempt at studying their semiotic backgrounds.

Hanoch Avenary suggests possible venues for such research in two concise articles (1971, 1979). The very title of the latter defines the question under investigation: “The Hasidic Nigun: Ethos and Melos of a Folk Liturgy.” In these two surveys, focusing on a few notations of Habad nigunim, Avenary suggests interpreting an elevation of the melodic line as a musical metaphor for spiritual ascent, repeating motives and temporary moves down as “efforts and backslides,” and, consequently, viewing the melodic demotion as a descent from the journey in the upper worlds. He also discerns proximity to speech intonation in several nigunim and emphasizes the significance of further inquiries into the semantics of musical forms and modal colorations within the genre.

These ideas have recently been developed by Raffi Ben-Moshe (2015), who focuses on the “contemplative” nigunim of the Israeli Habad Hasidim, and combines musicological analysis with verbal testimonies collected in fieldwork.[3] Edwin Seroussi employs a narrative strategy, analyzing “the conception, performance, and reception” of a single Habad nign, “Shamil”—allegedly of Caucasian origin—as a means to explore “the social, literary, and technological mechanisms that characterize music in Habad, past and present” (Seroussi 2017, 305). Yonatan Malin also suggests interpreting nigunim using narrative analysis, seeking “meaning by making connections between musical structure and stories” (Malin 2019, 115), providing solid theoretical justification for this methodology. However, thus far this suggestion has not been applied to any vast corpus or particular repertoire and remains therefore a contribution to the theoretical discourse rather than a practical tool for specific inquiries.

The primary reason for the scarcity of musicological research on the core central-eastern European nigunim repertoire seems to be the lack of a comprehensive understanding of the associations evoked by these tunes’ musical elements—rhythms, motives, forms, cadences, etc.—within post-vernacular contexts. This void is largely due to the annihilation of the European Hasidic communities during the Holocaust and the subsequent distancing of post- Holocaust congregations from the cultural contexts in which Hasidic music originally emerged. Although these displaced communities retained some aspects of their older musical traditions, the broad censorship in ultra-Orthodox circles, which exert control over which nigunim may be sung and disseminated, along with technological shifts and internal political influences, led to significant and relatively swift changes in their music.[4]

This noteworthy change is tacitly acknowledged in an extensive study of a different sub-genre—the Israeli Hasidic dance-nigunim repertoire—by Yaakov Mazor, André Hajdu, and Bathja Bayer (1974). Analyzing 250 dance-nigunim selected from approximately 400 documented through fieldwork in Israel, the authors make three choices that distinguish this repertoire as a new phenomenon in its own right, one that is only partially related to the central-eastern European tradition. First, they choose to include melodies historically unrelated to the older nigunim traditions in their corpus: tunes of local Mediterranean origin, klezmer tunes, and melodies of Yiddish popular and Hebrew quasi-Hasidic songs that were instrumentally performed at Israeli Hasidic weddings. Second, they intentionally do not relate to the historical dimensions reflected in attributions to specific courts and in the extant documentation of the nigunim in prints and manuscripts. The decision not to mention attributions to dynasties, the authors explain, is because numerous dance nigunim were shared by various courts, and thus represented a “pan-Hasidic” popular repertoire. Finally, most of the nigunim included in the corpus are transcribed from the instrumental performance characteristic of Israeli Hasidic music. This type of dissemination of Hasidic music was less prominent in eastern Europe, where the art of klezmer, i.e., the traditional instrumentalist, was not necessarily linked to Hasidism, and where the main performance context of nigunim was not weddings, but rather singing on Sabbaths, when playing instruments was forbidden. Consequently, and although this is not the main purpose of their study, Mazor, Hajdu, and Bayer clearly demonstrate that the dramatic relocations of Hasidic communities to new geographical, political, and cultural frameworks were accompanied by rapid musical changes. The relocations led to the emergence of a new Hasidic repertoire, an Israeli one, in which Arabic and Turkish tunes, new Yiddish theater melodies, Hebrew quasi-Hasidic songs, and old Hasidic nigunim coexisted, sharing new performance contexts, musical settings, and melodic features.

An attempt to reconstruct the partially lost richness of associations evoked by central-eastern European nigunim can be approached using historical-ethnomusicological methods. The morphological analysis of a representative corpus and the interpretation of its features in the framework of the historical contexts of its formation can be valuable. For this purpose we will examine nigunim attributed to the prominent traditional musician Yosl Volynets “Tolner” (1857?, Talne–1919, Novomyrhorod).[5] First, we introduce the historical backgrounds of their emergence and reception, as well as the cultural and social significance of a Hasidic composer. Second, we look at the tish-nign’s stylistic features through the lens of those belonging to this corpus. Following that we study the tish-nigunim attributed to Tolner in relation to non-Hasidic genres and then against the backdrop of other contemporaneous musical contexts, comprising a “musical polysystem.”

Why Study Nigunim Attributed to Yosl Tolner?

Yosl was the house composer in the Hasidic court of a highly influential spiritual leader, R. Duvid Twersky (1808–1882) of Talne (Yiddish spelling: Tolne; in Russian: Talnoye); hence his nickname “Tolner.”

While the attribution of tunes to Yosl is based on oral tradition and cannot be definitively verified without authorized manuscripts, its persistence is a significant historical phenomenon in itself and therefore its survival in specific cultural and musical contexts calls for a phenomenological analysis. In particular, exploring the following dimensions can shed light on the musical significance of tunes ascribed to Tolner: the mutual influences of male and female traditional creativity; perceptions of conservatism and innovation, and notions of temporality in general; attitudes towards local identities and transnational networks; and musical dialogues with both internal traditions and external influences—from Polish and Russian elites, as well as from Ukrainian peasant culture. A close examination of these reference points within a representative corpus will allow us to trace the aesthetic foundations and uncover the musical meanings embedded in the broader tradition of Hasidic nigunim as it developed across vast territories beginning in the late eighteenth century.

The nigunim ascribed to Yosl Tolner (henceforth: Tolner’s nigunim) thus offer a particular case through which this genre is exemplified and can be better understood, even though his authorship remains unconfirmed in some cases. The factors that dictated my choice to focus on these melodies are the historical contexts that shaped the musical idiosyncrasy of the nigunim of the Hasidic courts originating in the Russian Empire and the stylistic proximity of Tolner’s nigunim to this vast corpus; a general acknowledgment of Tolner’s nigunim as particularly beautiful ones; and, finally, the significance of the agency of the underexplored figure of the Hasidic court composer. These factors are elaborated below.

Historical Contexts

The Napoleonic Wars divided eastern Europe’s Hasidim into two camps: Russian and Polish. The centuries-long cultural, economic, and political differences among the different regions inhabited by eastern Ashkenazim, which since the seventeenth century had been reflected in the emergence of three Yiddish dialects (Lithuanian Yiddish in the North, Polish and Ukrainian Yiddish in the South), intensified, despite numerous business and family ties.[6] These differences found expression in music: While a significant portion of Polish and western Galician nigunim tended to an openness to the western European musical fashions and accumulated chordal thinking, waltz-like and march-like melodies, and some operatic gestures, numerous nigunim by the Ukrainian and Lithuanian-Belarusian Hasidim adhered more closely to the preservation of old-style patterns. This does not mean that all Polish Hasidim abandoned their old nigunim. However, their openness to Western fashions and continual musical innovation became a discernible trend, one that was less characteristic of Russian courts. Meanwhile, constant migrations, along with marriages between the two groups, generated an awareness of the stylistic differences, curiosity about and inspiration by the music of the other side, and, as a result, a steady musical exchange. The comparison between the nigunim attributed to Yosl and nigunim from other “Russian” areas reveals that most of them follow the old-style patterns, which will be discussed further below. Nonetheless, a number of nigunim ascribed to him do correspond with the nineteenth-century “Polish,” that is, westernized, new Hasidic musical styles; these will be discussed separately.

Reception

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the nigunim that Yosl created were communally considered of the highest quality; they thus eventually spread throughout the entire Yiddish-speaking world, far from the small Ukrainian towns in which Tolner resided and worked.[7]

Among the verbal and other testimonies to the wide reception of his nigunim is their use as metonymic representations of Hasidism in several parodies. For example, a melody of Yosl’s nign, which an informant, Aron Lantsman (born 1890), learned directly from Yosl—thus confirming the accuracy of this attribution (Beregovski 2013, #52)—was parodied by Yitskhok Reingold (1873–1903) in his satirical song “A Juhr Noch der Chasene” (“A Year after the Marriage”), released in 1916 by Columbia Records (E3105).

An additional testament to the popularity of Tolner’s nigunim is their being sung as traditional “folk tunes,” unrelated to the Hasidic court of Talne. Probably the most famous of them today is the Hebrew Purim song “Chag Purim,” (“The Purim Holiday”), which appears to be an abridged variant of a nign recorded by Shimen Dobin in 1916. The same song was recorded in 1945 by Lantsman, who acknowledged its authorship by Tolner (Beregovski 2013, #164). Its arrangement by Arno Nadel appeared in 1910 under the title “Hasidic Melody” (Nadel 1910, 101–4). Two years later it was published by Zussman Kisselgof (1912, 6) as the Sabbath chant “Menucha ve-Simcha.” The earliest documentation of the attachment of the Hebrew words “Chag Purim” to this nign is from 1923 (Kipnis 1923, 83). Two other tunes that Lantsman ascribed to Yosl are still sung today by religious Zionist families. One—performed as the Sabbath-table chant “Yom Shabaton” (“The Day of Sabbath”)—appeared as early as 1927 in a collection of Lithuanian Jewish tunes (Bernstein [1927] 1958, #95), in which it is cited as collected from Mr. Zeydman, a dweller of Vilnius. The second one (see example 11 below) is sung today to the words of the Sabbath liturgical chant “Lekha Dodi Likrat Kalah” (“Come Out My Beloved, the Bride to Meet”), and believed to be widespread among the Hasidim of Bratslav; it was documented in Vilnius as well (Bernstein [1927] 1958, #28). A nign recorded when Yosl was still alive, in 1916, by I. Dubrovinski, born in 1882 in St. Petersburg (Beregovski [1946] 1999, #34), is known among today’s Habad Hasidim as “Reb Yehude Heber’s (or Eber’s) Nign.” In all probability, Yehude Heber (1901–1941) learned it at the prominent Warsaw Habad yeshiva, “Tomkhei Tmimim,” from students who had arrived from Ukraine. All these attest to the wide and rapid reception of Tolner’s nigunim.

The Hasidic Composer

Along with representing the less westernized Hasidic music that gained wide admiration, Tolner’s creativity opens a window to the study of the contribution of the Hasidic court musician to the formation of the nigunim tradition. Nigunim composed by special musicians who were engaged by the Hasidic court, like Tolner was, comprised one of the three large components of the repertoire. The two others are nigunim composed by Rebbes, and thus serving as musical symbols, and nigunim whose authorship was considered insignificant by the performing community.

Nigunim ascribed to Rebbes, quite diversified in their musical features, enjoyed a special sanctity and prestige. But whether their popularity was caused by or led to their attribution to many specific Hasidic leaders should be further examined. Indeed, numerous well-known nigunim are attributed simultaneously to different leaders by different courts, signifying more about their popularity and extramusical meanings than about the historical contexts of their emergence.[8]

The “nigunim of insignificant authorship” consisted mainly of instrumental (klezmer) tunes adapted for vocal performance; short tunes initially composed as cantorial fragments and borrowed later for Hasidic paraliturgical performance outside the synagogue; and, finally, traditional melodies of paraliturgical chants, such as Sabbath zmires (Yiddish; from the Hebrew zemiroth—chants) , that evolved in the eastern Ashkenazi communities before the emergence of Hasidism and gradually penetrated the Hasidic repertoire. The inspirations of klezmer, cantorial music, and zmires are apparent in the scholarship of Beregovski, Idelsohn, Feldman, Avenary, and Lukin. Feldman (2016, 236) cites Mark Slobin’s unpublished English translation of Beregovski’s introduction to his collection of Hasidic tunes (Beregovski [1946] 1999, 16–17), in which the influence of klezmer and paraliturgical chants is highlighted:

Textless songs have probably been common in Jewish life for a long time. This could be connected with the fact that on religious grounds the playing of musical instruments was not permitted on the Sabbath and on holidays. Dance melodies were sung at community celebrations and family gatherings.… Textless songs and melodies for the Sabbath hymns were widespread in places and regions in which Hasidism had almost no adherents, and also among the fervent and active opponents of Hasidism (Misnagdim).… They made fun of the ecstatic movements of the Hasidim during prayer, their feasts, etc. We never hear, however, the opponents of Hasidism criticize the fact of using the melodies themselves. From this we can conclude that the genre of textless melodies was an old tradition in Jewish life, and the leaders of Hasidism made broad use of it.

Furthermore, Abraham Idelsohn (1932, xiii), Hanoch Avenary (1979, 163–64), and Michael Lukin (2020, 106–7) discuss melodic proximities between rhythmic liturgical melodies from eighteenth- and early nineteenth–century cantors’ manuscripts and nigunim, assuming an ongoing exchange between the two repertoires. As Eliyahu Schleifer and Judit Frigyesi have commented, some nigunim were in fact rhythmicized versions of a liturgical cantorial recitative; on the other hand, cantors used to incorporate rhythmic nigunim in order to engage the audience in collective singing (Vinaver 1985, 147; Frigyesi 2008, 1222–1225). The very emergence of the nigunim repertoire might have been inspired by this custom of incorporating rhythmic melodies into cantors’ singing, as well as by prolonged cantorial vocalizations sung without words. Apparently, this practice fostered the shared musical scales in cantorial and Hasidic tunes.

Schleifer points, inter alia, to a few additional sources (Vinaver 1985, 191–92): anti-Hasidic maskilic parodies and Jewish theater songs, which, over time, were adopted into the Hasidic repertoire after their mocking origins were forgotten; some non-Hasidic yeshiva songs; imitations of shepherd songs; and rarely documented tunes sung by Hasidic women for themselves. Yet, while nigunim of these sources exemplify the vibrant dynamics of a living tradition, they comprise less than 1 percent of the documented nigunim repertoire. Thus, klezmer, traditional paraliturgical, and cantorial melodies remain the primary sources of nigunim of unknown authorship in the central-eastern European Hasidic tradition.

The music of Hasidic composers employed by Rebbes stands apart from the other two large groups. On one hand, the attributions to these composers were meaningful to the tradition-bearers and should be studied as such. On the other hand, unlike attributions to prominent leaders, those attributed to the court composers served more as markers of belonging to a particular dynasty than as indicators of special sanctity or mystical meaning, and therefore hold greater potential for historical accuracy. Although the creativity of these composers is less studied as a phenomenon, it appears to have been quite significant. Hajdu and Mazor (2007, 408) name only a few such Hasidic composers:

Many Hasidic leaders…cultivated their communities’ musical repertoire and encouraged original creativity, or drew gifted composer-hazanim…to their “courts.” Very famous were the hazanim Nissan Spivak (“Nissi Belzer,” 1824–1906) in Sadigora, Yosef Volynetz (“Yosl Tolner,” 1838 [sic]–1902 [sic]) in Talnoye and Rakhmistrivke (Rotmistrovka), Jacob Samuel Morogovski (“Zeydl Rovner,” 1856–1942) in Makarov and Rovno, Pinhas Spector (“Pinye Khazn,” 1872–1951) in Boyan and its branches, and the menagnim (musicians) Yankl Telekhaner in Koidanov, Stolin, Lechovitch, and probably Slonim, and Jacob Dov (Yankl) Talmud (1886–1963) in Gur.

Zalmanoff (1948) includes nigunim by and information about traditional Habad composers in his anthology: Hilel Ben Meyer Haleyvi (1795–1864); the Althoyz family—Binyomen (1869–1928), Elyohu–Khayim (1870–1941), Pinkhes–Todres (1897–1963), and Shmuel–Betsalel (1910–1985); and the Kharitonov family—Aharon (1876–1933), Avrom (?–?), Sholom (1886–1934), and Shimshen (1918–2009). Several dozen nigunim attributed to other Hasidic composers are available at the Sound Archives of the National Library of Israel. The study of the legacy of one such Hasidic pre-Holocaust court musician can shed light on the nature of his agency, as it explores perceptions of self-expression, attitudes toward surrounding musical creativity and toward the craft of the semi-professional musician, and the dynamic interplay between conservatism and innovation as traced in his music.

Moisei Beregovski attempts to adumbrate stylistic features of the nigunim ascribed to Yosl through a comparative analysis of their different versions (Beregovski 2013, endnote 52), and reaches three main conclusions. First, even those informants who learned the nigunim directly from Yosl’s lips made significant changes when reproducing them. The peculiarities of the chains of transmission must be considered when evaluating Yosl’s compositions. Second, a typical feature that appears in several of Yosl’s nigunim is an anhemitonic trichord—a movement on the sounds of an ascending fourth between the first and fourth degrees of the natural minor, skipping the second degree (in G minor: g–b♭–с’). Finally, Beregovski notes that due to the scarcity of documentation, it is impossible to determine whether this melodic pattern was introduced by Yosl and subsequently influenced other tunes or was borrowed by him from the melodies of his surroundings. This last uncertainty appears to have been influenced by the Soviet climate that existed in ethnomusicological discourse during the 1930s and 1940s (Lukin 2024; Feldman 2016, 133–35). The vast documentation of tunes from a variety of east-Ashkenazi traditional musical genres, collected by Beregovski himself, demonstrates the wide spread of melodic patterns like this one, all revealing proximity to old anhemitonic motives. There is no doubt that Yosl acquired and preserved this premodern musical tradition, honoring the old eastern-Ashkenazi musical language.

In all probability, Beregovski’s reservations hint at what is left unsaid: the folk composer’s individual style is irrelevant. Unlike composers of nineteenth-century classical music, the creators and performers of Hasidic music—and Yosl among them—did not aim to express their individuality or subjective interpretations but rather to reveal the beauty and aesthetic potential of eastern Ashkenazi traditional musical patterns. When reproducing Yosl’s nigunim, folk singers sensed a freedom to recreate them through performance, according to the unwritten canonical laws known to them, acquired unconsciously; Yosl’s “copyright” was not perceived as important. Moreover, Hasidim were convinced that they sang the original version as they knew it; only musicological comparative analysis reveals significant differences between different variants, all considered “original.” These differences reveal unconscious—though legitimate—changes.

Tolner’s nigunim thus accord with Galit Hasan-Rokem’s definition of the dimension of “tradition:” they emerged against the backdrop of “the group’s concept that their cultural heritage contains traditional values and modes of expression that are transmitted from generation to generation…one of the means by which the historical-chronological identity of the group is strengthened and its continuity sustained” (Hasan-Rokem 2002, 957). The attribution of particular melodies to Yosl should, first, be understood as a marker of belonging to certain territorial and temporal frames of reference; second, be seen as a marker of high quality, indicating genuine exemplars of traditional creativity, as they were composed and performed by a master; and third, consequently, make these nigunim much more valuable.

Stylistic Features of Tish-nigunim

Further analysis positions Tolner’s nigunim in the general context of the eastern-Ashkenazi musical landscapes. The manuscript that Beregovski prepared for publication in 1946, and which was later published as a facsimile in 2013, is the main source of the present study; it documents Tolner’s nigunim in Ukraine during the first half of the twentieth century (Beregovski 2013). The first nign to be analyzed here is “Nign no. 99” from that collection. It was sung to the prominent Yiddish music collector and educator Zussman Kisselgof in 1913 (that is, when Yosl was still alive) in the Volynian shtetl Dubno (northwestern Ukraine).[9] The informant, Yisroel Friman, forty-two years old and a “bal-tfile” (second cantor), reported that he had learned the nign from Yosl himself.

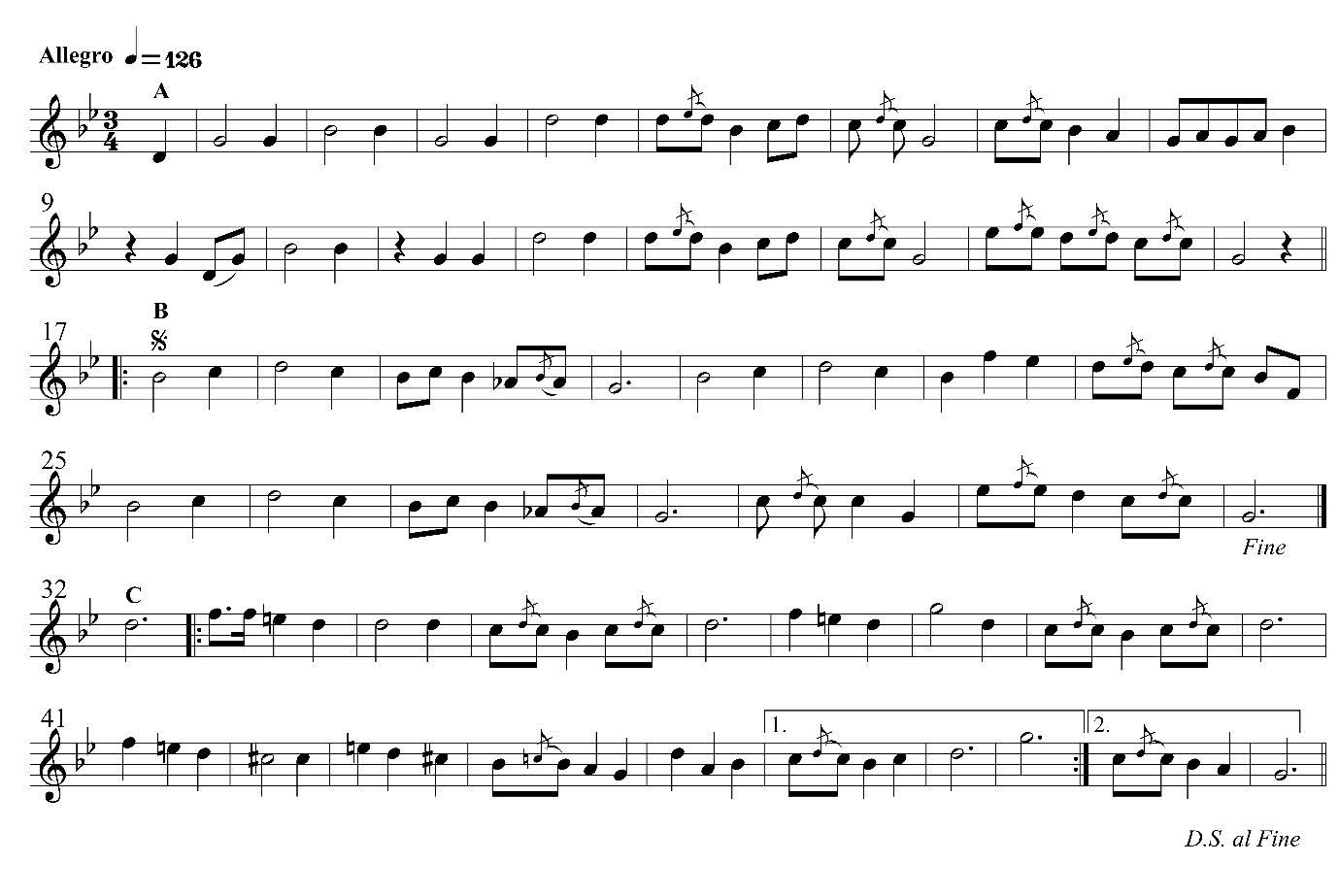

Example 1. Beregovski 2013, #99. For the original (1913) audio-recording transcribed by Beregovski, see no. 30 at https://www.audio.ipri.kiev.ua/CD5.html.

Six features characteristic of numerous old-style tish-nigunim from Ukrainian and Belarusian courts (e.g., from the Russian world rather than the Polish) stand out in this nign: (1) ascending development of the melodic contour; (2) structural complexity (especially striking given the oral transmission); (3) modality resembling both cantorial singing and klezmer tunes; (4) rhythmic diversity; (5) conciseness of melodic patterns; and finally, (6) somewhat mysterious uncertainty regarding the nign’s association with other musical genres.

Ascending Development of the Melodic Contour

The upward movement is distinct from the very first sounds: in the first four measures the melody rises one octave, and then lowers only minimally toward the end of the first half-period (measures 1–8); the second half (measures 9–16) expands the range’s high limit further (up to e♭’), as do the following parts, B and C (mm. 17–24, up to f’; mm. 32–48, up to g’). A sense of elevation stems from the frequency of the third degree (b♭) throughout all four parts of the ABCB form. Alongside the aforementioned interpretation of the melodic ascent as a musical metaphor, Hanoch Avenary discerns the semantics of the third degree’s centrality: “a half-clause on the minor Third, often found in early Hasidic melodics [is] an undecided, suspended turn of tonality which may be understood as an expression of the unworldly and mystical” (Avenary 1979, 160). A melodic turn, compatible with this characterization, appears in measure 8, and is developed further in measures 17–24.

Structural Complexity

The four-part musical form ABCB is one of the most frequently used in the corpus of Hasidic nigunim, with the penultimate C usually preceded by a “signal” (d’, measure 32). Part C represents an emotional peak and brings in significant changes in the modus, in melodic contour (more descending motives than in parts A and B), in rhythm (a new pattern of ♩♩♩ | 𝅗𝅥 ♩), and in ambitus (g–g’).[10] The four parts maintain inner ties: the closures of A and B are identical (measures 15–16 and 30–31), and the centrality of the fifth degree (d’) is shared by all four.

Modality Resembling Both Cantorial Singing and Klezmer Tunes

Each part of the musical structure is marked by a different modal color.[11] Part A displays the “natural minor quasi pentatonic” mode, i.e., the minimal use of the second and sixth degrees of the natural minor (the a sound appears just three times in two adjacent measures, as one quarter-note and two eighth-notes in measures 7–8; the e♭’ sound appears only twice, and in only one measure, namely, as two eighth-notes in measure 15). Part B introduces the modal change by presenting the lowered second degree a♭ and the subtonic f, which did not appear before. In B, an ambiguity emerges regarding the alleged shift to the relative major on b♭, which also serves as a modal coloration. A shift to the “Altered Dorian” (i.e., to the traditional scale g–a–b♭–c’♮/c’#–d’–e’♮–f’♮–g’) in C has been noted. The natural minor with a lowered second degree, the plagal clause (d’–c’–g), and the Altered Dorian mode are all shared by klezmer and cantorial music.[12]

Rhythmic Diversity

Rhythmic diversity is achieved through the constant juxtaposition between two contrasting formulas: a) 𝅗𝅥 ♩ and b) ♫♩♫. It is instructive that the emerging rhythmical symmetry is destroyed at the very beginning, by means of the syncopation (measures 9, 11); the aesthetic ideal of rhythmic diversity dictates variation in rhythm rather than repetition. In A, the second formula is only introduced in the fifth measure, while in B, it appears in the third measure; C introduces an additional rhythmic pattern (♩♩♩ | 𝅗𝅥 ♩).

Conciseness of Melodic Patterns

In contrast to this multiplicity of different rhythmic formulas, a fairly monotonous development of the melodic contours stands out in each of the four parts. This feeling is dictated by the scarcity of their central sounds: in A, these are just g–b♭–c’–d’, with the modest addition of the adjacent d, a and e♭’; in B, the central sounds remain the same, but this time the lower dominant d is replaced by the subtonic f, the second degree a is lowered to a♭, and the set of adjacent sounds is expanded by the addition of the seventh-degree f’. In C, other sounds are used, but they remain succinct: the most frequent sounds here are those of the pentachord f’–e♮–d’–c’(or c#’)–b♭—each appearing 8 quarters or more out of a total of 93 quarters in C. Three other sounds are added to this compact set, each appearing in 5 quarters out of 93: g’, a, g. Such compactness creates a somewhat introverted mystical atmosphere. It reminds the performers that the tune fulfills a mystical function and that its purpose is not recreation, echoing the aforementioned distinction by R. Yankev-Yoysef between tunes of devotional intention and those for one’s pleasure. Avenary’s notion regarding the melodic proximity of numerous nigunim to a form of transcendent speech is another outcome of this limited number of different sounds in each part. It is thus yet another stylistic pattern shared by numerous nigunim.

Multiple Associations: Tish-Nigunim and Other Musical Genres

The combination of all these features causes a sense of ambiguity of genre (feature 6). The tune begins similar to a waltz, but then mazurka-like rhythmic patterns appear. However, very soon the feeling of the dance movement is contradicted by the monotonous melody’s moving in place and the abundance of prolonged sounds (𝅗𝅥, 𝅗𝅥.), which create an atmosphere of meditation. This atmosphere is supported by the liturgy-like modality and the complex formal structure, resembling a journey from the lower worlds in A to the upper ones in C. Characteristically, these ties to old-style music that crystallized long before the emergence of Hasidism are mixed with traces of contemporary nineteenth-century western-European musical patterns, such as the typical half-cadence and full-cadence (measures 47–50). Altogether, these colors convey the cultural realm of the eastern Ashkenazim—their location at the crossroads between rural areas and bigger towns, between premodern Polish-Lithuanian heritage and the innovations of imperial modernity, between strong traditional conservatism and an apparent psychological flexibility concerning novelty, thanks to their social mobility and overall literacy. These musical colors also appear to embody the Hasidic philosophy of music as an art belonging simultaneously to different spheres, both sacred and mundane (Mazor 2002), and the aesthetic and cultural orientation toward the non-Jewish elite, which finds expression, inter alia, in the Hasidic ideal of kingship (Assaf 2002).

We will look at three additional nigunim attributed to Tolner, all of which share most of the old-style features identified in example 1. Each also reflects a distinct source of inspiration: the first draws from klezmer repertoire, while the latter two are influenced by Yiddish folk songs.

The Tish-nign and Klezmer Music

Example 2. “Tish nign” (“Table chant”), Beregovski 2013, #13, https://nigunimbimbom.org/64 (henceforth, URLs are provided for MIDI audio recordings made from the transcriptions)

The features shared by examples 1 and 2 can be briefly summarized as follows: First, in both, the ascending development of the melodic contour (in B and C) and half cadences on the third degree (in measures 4 and 9) are found. Second, the structural complexity of the ABCD musical form stands out. The emotional peak in C, which begins with a “signal,” brings in a new modal color and a new rhythmic pattern and expanding the ambitus. Mutual ties between the parts are apparent (A and B have the same final cadences in measures 5 and 11; A, C, and D contain the same emphasized sound c’). Third is the modality, which resembles both cantorial singing and klezmer tunes (A with a preference for the sounds of the anhemitonic tetrachord g–b♭–c’–d’ combined with a limited presence of the sound a; B with the subtonic f; C with a modulation from the natural minor to the major scale on its fourth degree; D with the modal ambiguity between C minor, linking the part to the preceding C major, and G minor, linking it at the same time to the G minor following in the repeating part A). Fourth we find rhythmic diversity (each part introduces a new rhythmic pattern). And, finally, the conciseness of the melodic development is noticeable (most parts of the nign are anchored in the interval of perfect fourth between g and c’, and, in C, within the interval of perfect fourth between c’ and f’).

An especially klezmer-like flavor characterizes this nign, particularly because of melodic turns which are not quite frequent in the vocal genres (such as the repeating fourth in measure 2 and the ascending combination of the major second and fourth in measure 8) and thanks to the ascending second inversion triad, typical of instrumental music (measures 13–14). As Beregovski emphasized, some nigunim were, in fact, instrumental klezmer tunes performed vocally on days when playing musical instruments was forbidden.[13] Others penetrated the klezmer repertoire in the opposite manner: initially created for singing, they were later performed instrumentally at Hasidic festivities due to their popularity.

And yet, this nign’s proximity to instrumental music—much like numerous other nigunim—appears to be a stylistic preference rather than an indication of real borrowing from the instrumental to the vocal repertoires. After all, while no evidence of the instrumental performance of Yosl’s tunes has survived, the nigunim themselves are too underdeveloped to be included in the klezmer repertoire, whether for listening or dancing. In the example under discussion, the change of tempo in C encourages collective joyful singing—while not being entirely suitable for dancing and somewhat awkward in the context of passive listening.[14]

The Tish-nign and the Yiddish Folk Song

The following nign (example 3) displays most of the features outlined above, illustrating their typological character:

Example 3. “Freylekhs” (“Joyful tune”), Beregovski 2013, #158a, https://nigunimbimbom.org/647

Among the typological characteristics that stand out are the ABCB musical form; a klezmer-like modality that combines harmonic and natural minor scales, incorporating a temporal modulation to the relative major; the ascending development of the melodic contour with the culmination in C, preceded by a typical “signal” (measures 34–35); and rhythmic diversity.

The sense of ambiguity, as observed in the previous two examples, is also apparent in this nign, marked by a certain inspiration from traditional Yiddish folk songs.[15] Since early modernity, the secular Yiddish songs sung by women and girls became an extremely common backdrop for tasks such as sewing, embroidery, plucking chickens, or sorting grains. Their melodies were simple and relatively short, with the lyrics the core element dictating the musical choices. Rhythmic diversification and the constant variation of the repeating stanza melody are among the musical features shared by most of them. Both reflect an idiosyncratic aesthetic ideal, and, at the same time, are an outcome of the prosodic features of the traditional poetic stanza: the latter typically adheres to tonic versification—maintaining a consistent number of stressed syllables while allowing the number of unstressed syllables to vary. Thus, the lyrics’ rhythmic flexibility dictates a corresponding melodic flexibility.

Several musical features link nigunim, such as the one in example 3, to the song tradition, notwithstanding significant remoteness between the genres. Indeed, nigunim represent a diametrical opposition to female Yiddish songs: nigunim are mystical, often sung publicly and loud, while involving deep emotional intensity rather than sung quietly during domestic work; they are male-oriented, usually structurally elaborate, and their words are either unimportant or nonexistent. However, the adherence of both genres to older eastern-Ashkenazi musical traditions, combined with the Hasidic ideal of sincerity and simplicity as a path to God, appears to form the foundation of the songs–nigunim continuum.

The musical proximity between example 3 and similar nigunim, on one hand, and traditional secular Yiddish songs, on the other, arises from a combination of characteristic “gestures”—musical patterns that signify specific associations familiar to eastern Yiddish speakers. These include the generally introspective atmosphere, strophic-like formal structure, variations on short melodic patterns, rhythmic flexibility, characteristic motives, and cadences. Some of these similarities are apparent from the comparison between example 3 and the four following melodies of Yiddish folk songs, examples 4–7, as summarized in table 1.

Example 4. “Her nor, du” (“Listen, you, pretty girl”), Cahan 1957, no. 78

Example 5. “Ikh hob gelibt” (“I loved a boy”), Cahan 1957, no. 11

Example 6. “In mizrekh-zayt” (“In the eastern side”), Cahan 1957, no. 28

Example 7. “Undzer unfang” (“The beginning of our love”), Brounoff 1911, no. 27

| Musical pattern | Measures in Ex. 3 | Measures in Ex. 4–7 |

|---|---|---|

| Opening d-g-(a)-b♭-(a)-g | 1–2, 5–6 | Ex.4, 1–4 Ex. 5, 1–4 Ex. 6, 1–2 |

| Closing c’-c’-f’-e♭’-d’-c’-b♭-a-g | 9-15 | Ex. 7, 8–9 |

| Closing d’-b♭-d’-c’-b♭-a-… d’-… b♭-a-g | 16–19, 24–30 | Ex. 5, 9–12 |

| Half-cadence f’-e♭’-d’-c’-b♭ | 48–51 | Ex. 6, 5–8 |

| Third degree of the natural minor as a resting point in the middle sections of the melody | 36–51 | Ex. 4, 5–8 Ex. 5, 5–8 Ex. 6, 5–8, 9–12 Ex. 7, 6–7 |

| Melodic pattern d’-g-b♭-(d’)-c’-b♭-a-(g)-b♭ | 11-13 | Ex. 4, 6–8 |

Table 1. Melodic resemblances between the “Freylekhs” nign (example 3) and four Yiddish folk songs (examples 4–7)

In addition to these melodic similarities, the abundance of repetitions and the resulting strophic-like structure of the nign under discussion recalls the Yiddish song-form.[16] This resemblance arises from the recurring closure, which functions like a refrain, specifically in measures 13–15, 28–31, and—due to section B’s repetition (“Dal Segno”)—again in measures 28–31 at the end of the nign. The repetition of melodic and rhythmic units, characteristic of the songs in examples 4–7, also stands out in the nign, creating another link between these two genres. Measures 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, 9–10, 16–17, 18–19, 24–25, and 26–27 all share the same rhythmic-motivic structure: in each pair, the first measure follows a rhythmic pattern that consistently contrasts with the second, the latter always featuring three descending notes in a rhythmic pattern of ♫ ♩ (or its variant ♫ ♪). The melodic development in part C is characterized by variative repetition as well, with all four of its phrases elaborating on the melodic progression b♭-c’-d’-e♭’-d’-c’-b♭.

A similar proximity is evident in another nign attributed to Tolner (example 8) and two additional melodies of Yiddish songs (examples 9–10), illustrating the songs’ echoes within the tish-nigunim corpus. These include the ascending minor sixth (measure 1), the use of the subtonic in the natural minor (measure 33), and a general sense of introspection created by the limited range and multiple repetitions of the same notes. As in the previous examples, these proximities coexist with the clear distinctions between the tranquil, simple songs of women and the Hasidic tish-nign. The latter is joyful, rhythmic, in a complex ABC form, and features a steadily prepared culmination in the C section, preceded by a “signal” in measures 18–21.

Example 8. “Nign,” Beregovski 2013, #46, https://nigunimbimbom.org/98

Example 9. “Zetst aykh nor anider” (“Just sit down you all close to me”), Cahan 1957, 182

Example 10. “Khane tsnue” (“Hannah the modest”), Lukin 2022, 129

Characterizing the affinity of Hasidic nigunim to Yiddish folk songs may contribute to our understanding of the sphere of emotions in the Hasidic world and the latter’s attitude towards female cultural realms. Although women did not have exclusive control over the repertoire of Yiddish folk songs, there is no doubt that they played a central role in its shaping. As for the place of women in Hasidic culture, thus far, it has been discussed primarily based on Hasidic texts and historical documents; according to both types of sources, their place was extremely circumscribed.[17] Therefore, it is especially important to emphasize the influence, even if indirect, of female creativity on one of the central axes in Hasidic life, the nigunim. Like the innovative lingual turn—extensive use of the Yiddish language, which earlier dominated literature for women and “men like women” (i.e., illiterate in Hebrew/Aramaic), in the early Hasidic literature (Kauffman 2013)—this musical dialogue with secular female songs attests to the complexity of gender perceptions within Hasidic creativity.

The Tish-nigh and Non-Jewish Popular Music

To complete our survey of the sources of inspiration, we must introduce the third secular genre that influenced nigunim, aside from klezmer tunes and Yiddish folk songs—pan-European non-Jewish popular music, as interpreted in the Hasidic courts.

The dialogue with western-European musical fashions, although more characteristic of Polish courts than of Russian ones, is nevertheless exemplified in the two following Tolner nigunim. The first tune, quite popular even today and usually ascribed to Bratslav Hasidim, resembles a waltz; it is symmetric, may be harmonically accompanied, is suitable for waltz choreography, and is light in mood.

Example 11. “Hamavdil” (“Nign for the End of Sabbath”), Beregovski 2013, #94, https://nigunimbimbom.org/333

Along with its proximity to the western European genre, this tune also reveals traces of an “old-style” nign: the natural subtonic of the minor mode, the ABCB structure, the presence of a signal before the culminating part C, a highly succinct ambitus of B, and the dominance of anhemitonic structures in the first twelve measures of C. Thus “Hamavdil” is an excellent example of a mixture of older eastern-Ashkenazi traditions and general western-European nineteenth-century fashions.

Another widespread pan-European genre that was very popular in the Hasidic milieu is the march. It, too, found its way to the repertoire attributed to Yosl, as in example 10:

Example 12. “March,” Beregovski 2013, no. 149, https://nigunimbimbom.org/638

Major scale, a simple melody, repeating rhythms, chordal thinking—all these turn this Hasidic nign into a joyful march typical of wind bands. Yet, again, as with the previous nigunim, it is apparent that the melody is not a real march, particularly due to the breaking of the quadruple symmetry in measures 21–23, 24–26, and 27–31 and the frequent use of fast notes instead of slow ones in the half-cadences, which discourages real marching. The complex formal structure, the presence of a signal at the opening of C, rhythmic diversity within A and B, the narrow range in B—all link this Hasidic march to the large corpus of nigunim.

The inspirations surveyed above, from klezmer music, Yiddish folk songs, and pan-European music such as the waltz and march, were introduced clearly and prominently in the above nigunim, chosen for the purpose of illustration. Although a significant quantity of nigunim like these exists, more often such associations are only hinted at by small musical gestures, less traceable for outsiders, and therefore less suitable for a musicological analysis. Nonetheless, the aesthetics and semiotics of the nigunim cannot be charted without relating to these connections.

The Tish-nign as Part of a Polysystem

Any examination of the central-eastern European tish-nigunim’s musical style must consider the characteristic features of Hasidic society—the ambiance of each Hasidic court and the trans-territorial nature of their expressive cultures—as well as the interconnected musical contexts of the Jewish realm and the surrounding musical landscapes. All these comprise a “polysystem”—a conglomerate of “open, dynamic, heterogeneous cultural systems,” as Moshe Rosman explains (2007, 93) while arguing for the contribution of this conceptualization to the study of the cultural history of eastern-European Jews (ibid., 82–110). The tish-nigunim as a phenomenon reveal the existence of an idiosyncratic musical polysystem, which will be elaborated upon below; we will look first at the social context and then move on to explore three different types of musical repertoires.

The Hasidic Court and Trans-territorial Connections

The paraliturgical ritual context of the nigunim’s emergence and performance at specific Hasidic courts determined the range of musical semantic meanings and thus dictated musical choices. Furthermore, local Hasidic traditions and Rebbes’ personal preferences certainly found musical expression in nigunim; this may be the reason for the scarcity of free-meter nigunim in the Ukrainian courts, compared with the wealth of such nigunim in other courts.

At the same time, numerous trans-territorial connections also had a strong impact on this repertoire. The traditional music of the eastern Yiddish speakers differed from that of their Slavic neighbors. Among the central factors dictating most preferences in non-Jewish eastern European traditional music (Ukrainian, Belarusian, Polish, Moldavian, Hungarian, etc.) was the connection of music to agricultural work and a fixed location. A strong attachment to place fostered the development of musical dialects and constant differences in ways of singing and choices of tunes, even between villages. In contrast, the Jews, who were not allowed to own land, and who—in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—were for the most part not permitted to settle in villages, were a mobile group. Thanks to this mobility, many nigunim passed from one Hasidic court to another. This was the result of marriage ties and the migration of the Hasidic leaders themselves, as well as performers’ indifference to the importance of preserving local tradition, unless dictated by Rebbes. Moreover, Hasidim often resided far away from their Rebbes, and every journey to the Rebbe was marked by learning new nigunim and singing them in distant localities; a new nign learned while visiting the Rebbe signified an intimate mystical connection to him. Mobility and its resulting steady renewal of the musical repertoire found support in the Hasidic philosophy of innovation and engendered an idiosyncratic sense of temporality, combining respect of the past’s sanctified musical markers with openness to the sounds of the most current present.[18]

Given all of the above, it is reasonable to discuss aesthetic norms of the broad Hasidic repertoire that developed in the numerous central-eastern European locations despite the uniqueness of each Hasidic court; each court contributed to its multifaceted fabric. Even the differences between Hasidim in distant regions, such as Ukraine and Poland, did not prevent mutual borrowing; thus, the nigunim composed by Yosl were adopted by the Habad and Karlin communities, both established in Belarus, and were familiar in Poland.

Urban European Music

At the broadest level of the interconnecting musical contexts lies the European musical landscape—musical sounds from urban repertoires, such as opera excerpts, orchestral “light” repertoire, music for domestic performance, and the like. This music reached the Yiddish-speaking community through various means, including performances on friars’ estates, military brass bands, itinerant singers who blended Western European-style melodies into their performances, and, finally, a particular element of the klezmer repertoire, identified by W. Z. Feldman as “cosmopolitan,” that was comprised of pan-European dance genres such as polonaise, polka, quadrille, and mazurka along with the aforementioned waltz and march (Feldman 2016, 196–97, 206–8). Yosl’s patron, Rebbe Duvid Twersky, had a unique collection of musical clocks, each of which played a popular classical tune (Minkovski 1918, 115, 120); the aesthetic norms of the western non-Jewish music, then, were shared among Ukrainian Hasidim, and musical resemblances with such tunes should be considered while examining the nigunim.

Indeed, although the majority of the nigunim repertoire was not distributed through channels accepted in western-European art music but rather was handed down orally and recorded in notation only in the second half of the nineteenth century, many nigunim conform to the aesthetic norms of European music: they are anchored in diatonic scales, for the most part, their musical form is periodic, and their rhythmic patterns are shared by the European musical genres of the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. Thanks to all these features, the nigunim repertoire fits into the general urban European fabric in certain ways, and can be perceived and analyzed, at least partially, with the tools fitting for the analysis of European music. Methodological tools used in the analysis of western European art music can be applied to the nigunim repertoire, as suggested by Avenary (1971, 1979) and Ben-Moshe (2015).

Rural Slavic Folk Songs

Since numerous Hasidic courts were located in small market towns, far from the big capital cities, most kinds of music, including even elite popular music, developed locally in these areas, surrounded by Slavic rural traditions, and thus sometimes echoed traits of peasants’ songs and dances. Such Slavic flavor did not mean massive accumulation of village melodies, but rather more general inspiration. The conscious Hasidic borrowings from the repertoires of the Slavs, as a mystical practice of “redemption of the sparks of holiness,” is often cited among the general public and in non-musicological scholarship on Hasidism. Nonetheless, such borrowings were, in actuality, quite rare. Joel Engel pointed this out as early as 1915, based on his close acquaintance with both Ukrainian music and Hasidic music (Gural’nik 2001, 119–64). A few years later, Abraham Idelsohn (1929, 417) also noted that while only very few direct borrowings took place, the most discernable affinity to non-Jewish Slavic music was rooted in imitation. That imitation applied to the urban, rather than rural, genres, such as the aforementioned military marches. However, central-eastern Slavic rural music did accompany the formation of the Hasidic repertoire in the first generations of Hasidism in Podolia, Galicia, and Volyn and during its further development in other eastern-central European territories. It is possible that this background is the reason nigunim often reflect Slavic inspiration in such features as collective performance, loud singing as an aesthetic ideal, moods of melancholy and longing, and stretching the boundaries of time by exceptionally prolonged

performance.[19] This inspiration may also explain the choice of key motives, such as plagal cadences (for example, d’–c’–g in G minor), quasi-pentatonic sequences like those represented above, frequent use of natural subtonic in the minor mode, and numerous melismas. Musical links to neighboring traditions are apparent in the choices of scales—a clear preference for natural minor—and the integration of scales containing the interval of an augmented second (b♭–c# or a♭–b♮ in the scales on the tonic g), also documented in Ukrainian and Romanian folk music as well as in the music of smaller local ethnic groups, such as Roma.

Despite clear affinities to European urban music and the Slavic rural environment, the differences between them and nigunim are also evident. First, most of the nigunim were monophonic songs, far from either harmonic-functional thinking or the numerous types of polyphony and heterophony dominating, respectively, eastern Slavic urban and rural music. Second, their public performance was limited to men only, unlike numerous traditional eastern Slavic repertoires which allowed mixing genders or were purely female. Finally, the Hasidic musical expression was mainly derived from intra-Jewish repertoires: the liturgical music; the tradition of chanting Sabbath paraliturgical table-songs (zmires) that took shape in the early modern period in western and central Europe and continued to develop among eastern Yiddish speakers; the klezmer melodies; and the Yiddish folk songs. These affinities represent the third context—the eastern-Ashkenazi.

Music of the Jewish Realm

As a derivative of this context, the nign differs and, at the same time, corresponds with the other musical genres of the eastern Ashkenazi world, as demonstrated above. Let us summarize these interconnections as elaborated by aforementioned scholars and our analysis.

Liturgical singing: Similar to this prominent component of that world, the nign is a vocal genre that was performed by men and fulfilled a mystical/religious function. Nonetheless, the former cannot exist without reference to the texts it serves. Not so the latter—the words, even if they exist, are intentionally insignificant in this kind of singing; furthermore, most of the nigunim, as mentioned, are songs without words.

Beyond that, the aesthetics of liturgical music include a clear distinction between the soloist (cantor) and the audience (congregation), which listens quietly and at times joins in the singing. At peak moments of the eastern-Ashkenazi liturgy, the audience expects to reach catharsis through tears as a result of listening to the cantor’s voice, and focuses on aesthetic appreciation. These audience expectations dictate the nature of the cantors’ voice production, which combines, inter alia, vocal colors shared by cantors and opera singers with vocal nuances reminiscent of crying. This voice production has not been observed in ethnographic recordings of nigunim from the beginning of the twentieth century; there is no evidence of its existence in earlier periods; and it is also not typical of the singing of nigunim in the post-Holocaust Hasidic communities. On the contrary, many Hasidic thinkers opposed bitterness and sadness, preaching joy instead. It is therefore clear that the music they created was not intended to make one cry. Even the non-joyful tunes express longing rather than bitterness. Nor was this music intended to exhibit the artist-musician and his musical virtues, such as virtuoso singing, wide vocal range, length of breath, and so on. Instead, Hasidic singing practices emphasize partnership and the power of mutual support and of gathering around the Rebbe’s table. This is also true for those few nigunim that, due to their sanctity and/or complexity, have always been performed solo; the personal, subjective impact of the singer—a menagen (Yiddish and Hebrew: musical performer) often chosen by the Rebbe, or the Rebbe himself—is much less relevant to the mystical layer of the performance than the self-expression of a cantor in a synagogue or a klezmer soloist at a wedding.

Paraliturgical singing (“zmires”): This genre represents the prehistory of tish-nigunim. Zmires comprise an old musical repertoire, particularly developed in the Ashkenazi tradition, performed to special Hebrew/Aramaic texts during ritual meals around the table.[20] Tish-nigunim introduced significant innovations to this practice: they freed musical decisions from strict adherence to poetic prosody through singing without words, facilitating the prolongation of melodies, and shifted the custom of leading the singing from those able to read and pronounce the texts to a more collective performance style.

Klezmer music: The lack of separation between the artist and the audience and the lack of an expectation that the artist be admired likewise differentiate the aesthetic of the nign from that of klezmer art. Moreover, the melodic, modal, formal, and rhythmic options available to klezmorim, the semi-professional musicians who devoted a significant part of their lives to music, were infinitely richer than those available to Hasidim, ordinary people whose vocal abilities were rather limited. Nonetheless, the admiration of klezmer music and the desire to hear it on Sabbath and holidays, when playing instruments is prohibited, fostered much borrowing from the klezmer repertoire. What is more, klezmorim were invited to Hasidic courts to play at times when instrumental music was permitted (such as the end of Sabbath) and often used their instruments to perform nigunim that had initially been created as vocal compositions. Finally, the Hasidic innovation of prolonged religious dancing on Sabbath and certain holidays furthered the vocal performance of suitable klezmer tunes. As a result of these interrelationships, tish-nigunim, much like klezmer pieces, are usually anchored in multi-part forms, highlighting the uniqueness of each part, as demonstrated above.

Yiddish folk songs: Several nigunim reveal a clear affinity to this genre. Common to both genres is a desire to give expression to the murmurs of the heart; the music is available to an ordinary person lacking any training. Both repertoires also share the secondary dominance of the aesthetic function: even though the music must be beautiful, its beauty is never the main focus. The salient function in both repertoires is the emotive one, and in the nigunim, it is the mystical-ritual function that predominates. Alongside this similarity between Yiddish folk songs and nigunim, there is no doubt that the absence of words in the latter and the general orientation toward higher spheres and a connection with the universe[21] constitute a disparity between the two, which therefore represent completely different genres.

The following table summarizes the mutual affinities between nigunim, the other genres of eastern Ashkenazi music, and non-Jewish musical contexts:

| Features Shared with Tish-nigunim | Features Contrasting with Tish-nigunim | |

|---|---|---|

| Urban European Music | Certain motives Major and minor scales Certain rhythms Certain forms Certain generic typical features Public performance Domestic performance Trans-territorial connections |

Musical settings Voice colors Modes, scales, motives Language (in vocal music) Verbal and cultural meanings Performers and audience separated Listening vs. participation Virtuosity vs. simplicity-sincerity |

| Rural Slavic Folk Songs | Vocal Emotive dominant Collectiveness Prolongation Ties to the local musical landscapes |

Modes, scales, motives Structural complexity vs. simplicity Role of words Verbal and cultural meanings Voice colors Trans-territorial connections |

| Ashkenazi Liturgical Music | Vocal Religious Rhythmizing of the liturgical recitation Proximity to rhythmical cantorial refrains Proximity to wordless cantorial vocalise Modes, scales, motives |

Role of words Soloist and audience separated Listening vs. participation Voice colors Catharsis through tears vs. joyfulness Virtuosity vs. simplicity-sincerity |

| Zmires | Vocal Religious Performance contexts Modes, scales, certain motives |

Text-centered vs. music-centered, and thus: Adherence to prosody vs. wordless Limited length vs. prolongation Solo vs. loud collective |

| Klezmer | Collectiveness Modes, scales, motives, rhythmic patterns Same tunes Structural complexity and diversity |

Instrumental vs. vocal Soloist and audience separated Listening vs. participation Catharsis through tears vs. joyfulness Virtuosity vs. simplicity-sincerity |

| Yiddish Folk Songs | Vocal Domestic, non-stage performance Introversion Modes, scales, motives Emotive dominant |

Religious vs. secular Role of words Verbal and cultural meanings |

Table 2. Musical choices: Tish-nigunim as part of a polysystem

As table 2 illustrates, tish-nigunim do not fully align with any single Jewish or non-Jewish repertoire, yet they maintain numerous connections with all of them. Consequently, their aesthetics and semiotics must be analyzed within the context of this musical polysystem. Hasidic composers, such as Tolner, reflected its dynamic in their compositions, skillfully navigating between the stylistic preferences of individual Hasidic courts and the trans-territorial aesthetic norms of the broader Hasidic tradition.

Conclusion

The cultural idiosyncrasy of the eastern-Ashkenazi realm encouraged the formation of paraliturgical music, which evoked a wide variety of associations and which, at the same time, tended to differ from any other type of music, both within Jewish culture and in the surrounding Slavic cultures. The very attribution of a nign to Yosl Tolner, whether it was justified or not, indicates an awareness of the aesthetic value of the nigunim ascribed to him. Our musical analysis and consideration of verbal testimonies shed light on the musical semantic meanings and aesthetic preferences that took shape in this realm, marked by a unique combination of mobility and traditionality. The key to aptly describing this music lies in the multiplicity of associations it evokes, thanks to its openness to musical worlds that would otherwise rarely meet.

The Ashkenazi respect for musical conservatism and innovation in equal measure encouraged multidimensional correspondences within a musical polysystem centered around the nigunim —between personal and collective, male and female creativity, rural and urban, Jewish and non-Jewish, mystical/religious and secular, and local and trans-territorial traditions. Composers of nigunim, we find, strove to represent a broader Hasidic musical style rather than their own personal credos or creativity. These vivid dynamics attest to the nature and significance of the musical decisions made by the traditional Hasidic composers-performers and their audiences before the post-vernacular era.

Endnotes

[1] For updated surveys of the scholarship, see Feldman and Lukin 2017 and Seroussi 2019. Approximately 2,500 nigunim documented before the Holocaust are available through the digital ethnomusicological project NigunimBimBom (https://nigunimbimbom.org).

[2] Idelsohn 1932; Beregovski [1946] 1999; Avenary 1971, 1979; Vinaver 1985; Sharvit 1995; Gural’nik 2001; Ben-Moshe 2015; Feldman 2016, 238–40, 287–90; Lukin et al. 2020.

[3] For the critical evaluation of the methodology and conclusions of this pioneering study, see Greenberg 2016.

[4] See for example: Brown 2018, 518–20. For musicological scholarship based on fieldwork undertaken in these communities see: Mazor, Hajdu, and Bayer 1974; Koskoff 2001.

[5] For updated biographical and bibliographical details, see Radensky 2011, 164.

[6] Assaf and Sagiv 2013; Beider 2015, 288; Feldman 2016, 275–98; Biale et al. 2018, 291–386.

[7] Minkovski 1918; Reznitshenko 1936; Sholokhova 2009; Rechtman 2021, 226–34.

[8] Vinaver 1985, 133; Lukin and Wygoda 2017; Seroussi 2019, 218–19.

[9] On collecting different types of liturgical and paraliturgical Hasidic music on this ethnographic expedition see: Sholokhova 2009.

[10] On the centrality and symbolism of the ABCB structural pattern, see Beregovski [1946] 1999, 19; Sharvit 1995, xi. On the signal as a characteristic feature in nigunim see: Mazor, Bayer, and Hajdu 1974, 147; Vinaver 1985, 223. On the modal change as a musical expression of the spiritual peak, see: Avenary 1971, 638.

[11] I follow Yonatan Malin’s definition of the term “modality” (2016, 1). Shared modal usage within traditional eastern European Jewish music is extensively discussed by Feldman (2016, 375–83).

[12] For the traditional scales and modes shared by various genres of eastern Ashkenazi music, see Feldman 2016, 223–24, 238–47, 380–83; Sharvit 1995, xii–xxx; Beregovski 1946.

[13] Schleifer supports this idea (Vinaver 1985, 192).

[14] On the division of the Ukrainian klezmer repertoire into listening and dancing, see: Feldman 2016, 134–35 (and elsewhere).

[15] For the stylistic features of the traditional Yiddish folk songs see: Lukin 2020, 2022.

[16] On repetitions in the traditional Yiddish folk songs, see: Lukin 2020, 100–101.

[17] For a reassessment of the extant scholarship, see Wodziński 2013.

[18] On innovation and music according to R. Nachman, see: Haran Smith 2010, 176–91. Interpreting nigunim as transmitting new Hasidic insights also stimulated the spread of Yosl’s nigunim, as they metonymically represented the Rebbe of Talno.

[19] On these and the following features, see: Slobin 1980; Czekanowska 1990, 90, 135; Mozheiko and Survilla 2000, 791–95; Noll 2000, 808–9.

[20] On this genre in the historical perspective since the late early modernity, see Feldman 2016, 39–43; Lukin 2025.

[21] On “The Melody of the Universe” in the teachings of R. Nachman of Bratslav, see Haran Smith 2010, 84–93.

Bibliography

Assaf, David. 2002. The Regal Way: The Life and Times of Rabbi Israel of Ruzhin. Stanford Series in Jewish History and Culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Assaf, David, and Gadi Sagiv. 2013. “Hasidism in Tsarist Russia: Historical and Social Aspects.” Jewish History 27 (2–4): 241–69.

Avenary, Hanoch. 1971. “The Hasidic Niggun.” In Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Cecil Roth and Geoffrey Wigoder, 12:637–39. Jerusalem: Encyclopaedia Judaica.

Avenary, Hanoch. 1979. “The Hasidic Nigun: Ethos and Melos of a Folk Liturgy.” In Encounters of East and West in Music: Selected Writings, 158–64. Tel Aviv: Faculty of Visual and Performing Arts, Dept. of Musicology, Tel Aviv University.

Ben-Moshe, Raffi. 2015. Experiencing Devekut: The Contemplative Niggun of Habad in Israel. Translated by Jonathan Chipman. Yuval Music Series 11. Jerusalem: Jewish Music Research Centre.

Beregovski, Moisei. [1946] 1999. Evrejskie narodnye napevy bez slov. Moscow: Kompozitor.

Beregovski, Moisei. 2013. Jewish Musical Folklore. 5 volumes on 5 CDs. Vol. 4. Kiev: Dukh і Lіtera.

Bernstein, Avrom Moshe. (1927) 1958. Muzikalisher pinkes: Nigunim zamlung fun yidishn folks-oytser. New York: Cantors Assembly of America.

Biale, David, et al. 2018. Hasidism: A New History. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Brounoff, Platon. 1911. Jewish Folk Songs; 50 Songs for Middle Voice and Piano Accompaniment. New York: Charles K. Harris.

Brown, Benjamin. 2018. “Like a Ship on a Stormy Sea:” The Story of Karlin Hasidism. Edited by Yehezkel Hovav. Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History.

Cahan, Yehude Leyb. 1957. Yiddish Folksongs with Melodies. Edited by Max Weinreich. New York: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

Czekanowska, Anna. 1990. Polish Folk Music: Slavonic Heritage, Polish Tradition, Contemporary Trends. Cambridge Studies in Ethnomusicology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Feldman, Walter Zev. 2016. Klezmer: Music, History and Memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Feldman, Walter Zev, and Michael Lukin. 2017. “East European Jewish Folk Music.” Bibliography. Oxford Bibliographies. Jewish Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199840731-0155.

Frigyesi, Judit. 2010. “Music for Sacred Texts.” In The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, edited by Gershon D. Hundert, 2:1222–25. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Greenberg, Yoel. 2016. “Review of ‘Experiencing Devekut: The Contemplative Niggun of Habad in Israel,’ by Raffi Ben-Moshe.” Notes 73 (1): 120–22.

Gural’nik, Leonid. 2001. “K istorii polemiki Ju. Engelja i L. Saminskogo.” In Iz istorii evrejskoj muzyki v Rossii, edited by Leonid Gural'nik, 119–64. Sankt-Peterburg: Evrejskij obshhinnyj centr Sankt-Peterburga.

Hasan-Rokem, Galit. 2002. “Jewish Folklore and Ethnography.” In The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies, edited by Martin Goodman, 956–74. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hajdu, Andre, and Yaacov Mazor. 2007. “The Musical Tradition of Hasidism.” In Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., 8:425–34. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA.

Haran Smith, Chani. 2010. Tuning the Soul: Music as a Spiritual Process in the Teachings of Rabbi Naḥman of Bratzlav. IJS Studies in Judaica 10. Leiden: Brill.

Idelsohn, Abraham Zebi. 1929. Jewish Music in Its Historical Development. New York, NY: Henry Holt.

Idelsohn, Abraham Zebi. 1932. Gesänge Der Chassidim. Vol. 10. Hebräisch-Orientalischer Melodienschatz. Leipzig: Friedrich Hofmeister.

Kauffman, Tsippi. 2013. “Theological Aspects of Bilingualism in Hasidic Society.” Gal-Ed: On the History and Culture of Polish Jewry 23:131–56.

Kipnis, Levin. 1923. Macharozes: Zemiros umishchakim legan-hayeladim uleveth-hasefer. Frankfurt a. Main: Omanuth.

Koskoff, Ellen. 2001. Music in Lubavitcher Life. Music in American Life. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Lukin, Michael. 2020. “Servant Romances: Eighteenth-Century Yiddish Lyric and Narrative Folk Songs.” Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry 32: 83–107.

Lukin, Michael. 2022. “At the Crossroads: The Early Modern Yiddish Folk Ballad.” Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 40 (2): 105–42.

Lukin, Michael. 2024. “Method and Myth: M. Beregovski’s Contribution to the Study of the Traditional Yiddish Folksong.” In Folk Music Research, Folkloristics, and Anthropology of Music in Europe: Pathways in the Intellectual History of Ethnomusicology, edited by Ulrich Morgenstern and Thomas Nußbaumer, 107–42. Musik Traditionen 4. Vienna: University of Music and Performing Arts (mdw).

Lukin, Michael. [2025]. “Collective Singing in the Jewish Shtetl,” Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics, 19 (1) (forthcoming).

Lukin, Michael, and Matan Wygoda. 2017. “Darey mala im darey mata: nigunei r' Levi-Yitskhak me-Berditshev be-perspektiva historit,” In Rabi Levi-Yitskhak me-Berditshev: historia, hagut, sifrut venigun, edited by Zvi Mark and Roee Horen, 426–93. Rishon Letziyon: Miskal, 2017.

Lukin, Michael et al. 2020. “‘Nign 3’ from Beregovskii’s Jewish Folk Tunes Without Words: An Introduction to the Study of Hassidic Music in its Ukrainian Context.” Ethnomusic 16 (1): 141–57. [In Ukrainian].

Malin, Yonatan. 2016. “Eastern Ashkenazi Biblical Cantillation: An Interpretive Musical Analysis.” Yuval 10. https://www.jewish-music.huji.ac.il/yuval/22542.

Malin, Yonatan. 2019. “Ethnography and Analysis in the Study of Jewish Music.” Analytical Approaches to World Music 7 (2). http://iftawm.org/journal/oldsite/articles/2019b/Malin_AAWM_Vol_7_2.html.

Mazor, Yaacov. 2002. “Kocho shel ha-Nigun ba-hagut he-chasidit ve-tafkidav ba-havay ha- dati ve-ha-chevrati,” Yuval 7: 23–53.

Mazor, Yaacov, André Hajdu, and Bathja Bayer. 1974. “The Hasidic Dance-Niggûn: A Study Collection and Its Classificatory Analysis.” Yuval 3: 136–265.

Mazor, Yaakov, and Edwin Seroussi. 1990. “Towards a Hasidic Lexicon of Music.” Orbis Musicae 10:118–43.

Minkovski, Pinhas. 1918. “Mi-sefer hayai [From my life’s book].” In Reshumot, edited by Alter Druyanov, 1:97–122. Odessa: Moriah.

Mozheiko, Zinaida, and Maria Paula Survilla. 2000. “Belarus.” In Europe, vol. 8 of The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, edited by Timothy Rice, James Porter, and Chris Goertzen, 790–805. New York, NY: Garland Publishing.

Noll, William. 2000. “Ukraine.” In Europe, vol. 8 of The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, edited by Timothy Rice, James Porter, and Chris Goertzen, 806–25. New York, NY: Garland Publishing.

Radensky, Paul. 2011. “The Rise and Decline of a Hasidic Court: The Case of Rabbi Duvid Twersky of Tal’noye.” In Holy Dissent: Jewish and Christian Mystics in Eastern Europe, edited by Glenn Dynner, 131–68. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Rechtman, Abraham. 2021. The Lost World of Russia’s Jews: Ethnography and Folklore in the Pale of Settlement. Translated by Nathaniel Deutsch and Noah Barrera. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Reznitshenko, Yehuda. 1936. “Kocho shel nigun.” In La-Chasidim Mizmor, edited by Meir Shimon Geshuri, 105–12. Jerusalem: Hatchiya.

Rosman, Murray Jay. 2007. How Jewish Is Jewish History? Oxford; Portland, OR: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization.

Seroussi, Edwin. 2017. “Shamil: Concept, Practice and Reception of a Nigunin Habad Hasidism.” Studia Judaica 40 (2): 287–306. https://doi.org/10.4467/24500100STJ.17.013.8248.

Seroussi, Edwin. 2019. “Music.” In Studying Hasidism: Sources, Methods, Perspectives, edited by Marcin Wodziński, 197–230. Ithaca, NY: Rutgers University Press.

Sharvit, Uri. 1995. Chassidic Tunes from Galicia. Jerusalem: Renanot.

Sholokhova, Lyudmila. 2001. Phonoarchive of Jewish Musical Heritage: The Collection of Jewish Folklore Phonograph Recordings from Institute of Manuscripts. Kyiv: Vernadsky National Library.

Sholokhova, Lyudmila. 2009. “Hasidic Music from the An-Ski Collection: A History of Collecting and Classification.” Musica Judaica 19: 103–30.

Slobin, Mark. 1980. “The Evolution of a Musical Symbol in Yiddish Culture.” In Studies in Jewish Folklore: Proceedings of a Regional Conference of the Association for Jewish Studies Held at the Spertus College of Judaica, Chicago, May 1–3, 1977, edited by Dov Noy and Frank Talmage, 313–30. Cambridge, MA: The Association.

Slobin, Mark, ed. 2000. Old Jewish Folk Music: The Collections and Writings of Moshe Beregovski. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Vinaver, Chemjo. Anthology of Hassidic Music. Edited by Eliyahu Schleifer. Jerusalem: Jewish Music Research Centre, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1985.

Wodziński, Marcin. 2013. “Women and Hasidism: A ‘Non-Sectarian’ Perspective.” Jewish History 27 (2–4): 399–434.

Zalmanoff, Shmuel. 1948. Book of Chasidic Songs. Brooklyn, NY: Hevrat Nihoah.