Articles

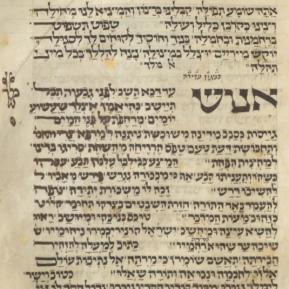

Niggun ‘Akedah: A Traditional Melody Concerning the Binding of Isaac

Niggun ʽAkedah is an Ashkenazi liturgical melody set to penitential poems referring to the Biblical episode of the binding of Isaac. Our study on the central role this episode played in medieval and early modern Ashkenazi Jewish culture reveals that, alongside a vast literary corpus in Hebrew and in Yiddish, there is a musical expression firmly entrenched with texts addressing this multifaceted religious theme.

Articles

Yom Yom Odeh: Towards the Biography of a Hebrew Baidaphon Record

Drawing on fieldwork undertaken in Beirut and Jerusalem, this article chronicles the present and past lives of a historical record of the Hebrew paraliturgical hymn “Yom Yom Odeh”. The record was released by the Lebanese Baidaphon company in the early 1920s featuring Ḥazzan Rafoul Tabbach. Since encountering it at a music archive in Lebanon and trying to find out more about its origins, I have played my digital recording of it to a variety of different people, including Syrian musicians, Lebanese record specialists as well as members of the Mizrahi community in Jerusalem. Within this context, the recording mediated and actualized memories of a cross-territorial, Arab-Jewish landscape and of musical exchanges that among other things saw the emergence of “Yom Yom Odeh”; at the same time, the recording provoked reactions that betray deep ideological divisions by which this landscape is scarred to the present day. Whether concerns about Jewish musicians’ national authenticity, my own anxiety about the song’s muted sound on my mobile phone, or nostalgic evocations of a city never seen, the different reactions that “Yom Yom Odeh” elicited capture tensions that arise from the song’s defiance to being constrained to the paragons of the Israeli-Palestinian/Arab conflict.

Articles

צלילי איוב במערב־התיכון של ארצות הברית: איש רציני יהודי לנוכח עץ החיים הנוצרי

Sounds of Job in the American Midwest: A Serious “Jewish” Man vs. a “Christian” Tree of Life

Ruth HaCohen (Pinczower)

The article discusses the soundtracks of two “Joban” movies whose plots take place in the 1950s and 60s in the American Midwest. The first film, the Coen brothers’ A Serious Man (2009), is “Jewish” in the sense that its protagonists are active members of a practicing Jewish community in a Minnesota suburbia. The second, Terence Malick’s Tree of Life (2011) is “Christian,” as it centers on a family who are members of a Catholic community in Texas. Both movies are autobiographical, as their authors attest. The article takes as its point of departure the long legacy of the Book of Job’s reception in each of the respective religious communities as well as their traditional contrasting approaches to questions of noise and harmony. It seeks to show the critical role played by the sonic dimension of the movies for fathoming their deeper meaning vis-à-vis their Joban orientation.

The article hinges on possible interpretations of Job 38, 7: “When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy,” which Malick took as a motto for his movie: Did the stars cum sons of God sing and shout in harmony, or did they produce noise? In theological terms, does the Book of Job, its finale notwithstanding, point towards salvation or disillusionment? And to what sort of salvation or disillusionment does it point, when viewed in terms of the movies’ retrospective gaze at the America of their childhood time?

In A Serious Man the major Joban figure, Larry Gopnik, a physics professor, is battered by a series of inflictions. Searching for a theological understanding of their meaning, he seeks out the council of three different rabbis - a modern version of Job’s three comforters. The music in his world, mainly diegetic and unequivocally non-celestial, derives from folk, liturgical, and popular genres. Yet, whether listening to music or producing it, the protagonists, I argue, mainly ventriloquized it, like a Dybbuk (a figure that features in the film’s opening episode). In their attempts to hide their purposes or conceal desires and agonies, all are possessed by certain spectral forces that speak or are heard through them. Sound thus points to what remains latent: a profound rupture from a troubled Jewish past, a rift between generations, phony piety, and above all, a deeply entrenched dissimulating social behaviour.

Of the three rabbis, only the oldest holds a key to understanding the root of Larry’s tragedies. To the ears of Larry’s bar-mitzvah son, the rabbi quotes the song’s lyrics the latter avidly consumes – Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love: “When the truth is found / To be lies / And all the joy / Within you dies.” Skipping the haunting refrain, the movie suggests that Larry, deprived of love, is the victim of other people’s bad faith (Sartre) and immoral actions. Fate, or God for that matter, is only marginally involved. Disillusioned and earthbound through and through, the movie’s final intertextual reference, I suggest, gives us a clue as to where its authors seek deliverance: somewhere over the rainbow - in an enchanted land of Oz – but not the one Job dwells in.

In Tree of Life the Joban lot is distributed among all family members, as all are afflicted by the death of the second son. Reflecting back on his childhood memories, the oldest son, decades later, wishes to work through this past that weighs so heavily on him. Grace vs. Nature, figured through a mother’s love and a father’s arbitrary law, respectively, are the major forces at work in this small universe. I argue that the rich soundtrack divides itself accordingly. Wavering between non-diegetic sound that turns diegetic, and vice versa, it dichotomizes Catholic to Protestant music from a J. S. Bach fugue to a Zbigniew Preisner Lachrymose. Postwar latency (Gumbrecht) prevails here, as it does in the Coen film, rooted in military traumas, professional failure, and an unspoken chasm between parents who unable to cope with their turbulent adolescent son. It likewise produces bad faith. Unlike the Coen film, however, here God’s presence is beyond doubt, and though He hides Himself, He is sought by the protagonists through passionate whispers. (God’s traces can be recognized in an evolutionary version of Whirlwind Revelation [Job 38-41]: His sublime Creation dazzles our eyes and caresses our ears, in the movie’s second prelude.)

In the end, as I interpret it, Grace prevails, and an “Agnus Dei” son is sacrificed by a mother-pieta to Berlioz’s purgatorial sounds. Malick, a frustrated philosopher, in this cinematic “Assumption” of the virgin-like mother, joins forces with Pope Pius XII’s 1950 dogmatization of Virgin Mary’s divine status. (A divination that Carl Jung saw as God’s ultimate answer to Job.) In the movie, a postmortem reconciliation reaches out to embrace all, enabling the prodigal adult son to restart his life.

The sublime vs. the grotesque; a divine mother sacrificing her son vs. a domestic deity (“Hashem”) who becomes metaphysically irrelevant – these two films move in opposite directions. The respective, concluding musical gesture in each – Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love' vs. Berlioz’ “Agnus Dei” – captures it all. Taken as a whole, the films thus artistically express significant trends in Jewish and Christian theologies, and wittingly or unwittingly, write new chapters in each.

The article is a chapter from a book manuscript in progress, on Job’s sonic adventures.

Reviews

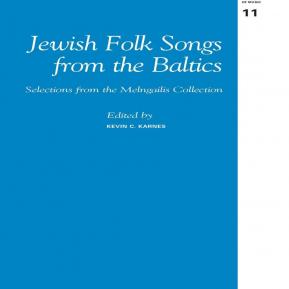

Review essay: Kevin C. Karnes and Emilis Melngailis, Jewish Folk Songs from the Baltics

Jewish Folk Songs from the Baltics makes public a forgotten source from the collection of the Latvian musician Emilis Melngailis (1874–1954), a devoted collector and scholar of folk songs. In addition to the Latvian folk songs Melngailis published in thirteen volumes, he devoted attention to the collection of songs from minority communities which inhabited Latvia, namely, Jews, Roma, Russians, Germans, Lithuanians, Poles, Belarussians, Latgalians, Livornians, and Estonians (p. xiv). Kevin Karnes took upon himself the daunting task of editing the Jewish items found in two notebooks from Melngailis’s collection (nos. 65 and 74). Melngailis started collecting Jewish songs in 1899 in Keidan (Lithuania), and continued this task in the 1920s and 1930s in Latvia after a long stay in Uzbekistan. (In 2015 The Archive of Latvian Folklore made the entire Melngailis collection available, including all of his 104 notebooks).

Reviews

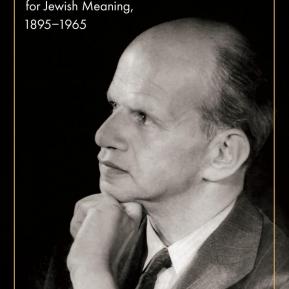

Book review: Hernan Tesler-Mabé, Mahler’s Forgotten Conductor

Biographical narratives are often based on the idea of historical influence: they aim at demonstrating how individuals altered the course of history (“made history”) and how they were affected by it. Yet the concept of historical “influence” does not emanate from the stratum of historical facts; rather, it is a construct that is imposed upon historical knowledge while assuming a distinction between particular agencies and general historical trajectories. Hernan Tesler-Mabé’s Mahler’s Forgotten Conductor: Heinz Unger and His Search for Jewish Meaning, 1895−1965 seems to question this assumption. Taking his cue from Carlo Ginzburg’s The Cheese and the Worms (1980 [1976]) — which explores popular culture in sixteenth-century Italy through the eyes of a common miller — Tesler-Mabé sets out to write a “contextual history” [sic.] in which a “single historical subject can open up an entire universe of understanding that otherwise would have remained unexplored” (5). This means that the differentiation between the personal history of a protagonist and a generalized historical context is replaced by the idea of historical embodiment; the historical subject, in turn, is construed as a site whose actions, demeanors, and dispositions weaves a web of mediators and contiguities. Untangling the knots of that web constitutes the act of historization.

Reviews

Book review: James Kaplan, Irving Berlin: New York Genius

If you want a bog-standard show-biz biography of Irving Berlin — chattily written, without enthusiasm for challenging any of the myths, giving its hero the benefit of the doubt in awkward situations (of which there are many), not showing much in the way of original research, and full of phrases (such as “in all likelihood’’, “perhaps he would have noted” and others) that give rise to authorial rambling and invention — this is maybe the book for you.