Malin, Yonatan. "Eastern Ashkenazi Biblical Cantillation: An Interpretive Musical Analysis." Yuval 10 (2016).

Eastern Ashkenazi Biblical Cantillation: An Interpretive Musical Analysis

תקציר באנגלית

Jewish cantillation—the intoned reading of Torah, Haftarah, and other Biblical texts in liturgical contexts—has attracted the attention of scholars ever since the day of the Renaissance Humanists. The Hebrew chanting depends on the text, and is determined by the te’amim (Masoretic accents) located above and below each word. However, the chant also has clear musical features, with a variety of scales, motives, contours, resting pitches, final pitches, and affects. In the present paper, I will provide a new perspective on musical features of Jewish cantillation in the Eastern Ashkenazi tradition, a tradition that developed in the areas that comprise today Lithuania, Belarus, Western Russia, Ukraine and Poland and is now widely practiced in Ashkenazi congregations around the world. There are six sets of melodies or “modes” in the Eastern Ashkenazi tradition of Biblical cantillation; I will characterize each mode with a variety of music-analytical tools (not only in terms of scales, as is often done), compare the modes with each other, and suggest hearings that link them with their respective texts and liturgical occasions.

Introduction

Jewish cantillation—the intoned reading of Torah, Haftarah, and other Biblical texts in liturgical contexts—has attracted the attention of scholars ever since the day of the Renaissance Humanists.[1] The Hebrew chanting depends on the text, and is determined by the te’amim (Masoretic accents) located above and below each word. However, the chant also has clear musical features, with a variety of scales, motives, contours, resting pitches, final pitches, and affects. In the present paper, I will provide a new perspective on musical features of Jewish cantillation in the Eastern Ashkdnazi tradition, a tradition that developed in the areas that comprise today Lithuania, Belarus, Western Russia, Ukraine and Poland and is now widely practiced in Ashkenazi congregations around the world. There are six sets of melodies or “modes” in the Eastern Ashkenazi tradition of Biblical cantillation; I will characterize each mode with a variety of music-analytical tools (not only in terms of scales, as is often done), compare the modes with each other, and suggest hearings that link them with their respective texts and liturgical occasions.[2]

I use the term “mode” in the way it has been used by ethnomusicologists and historians of Jewish music since Idelsohn—to refer not only to a scale, but also to characteristic motives, pitch relationships, affects, and associations of a given repertoire (see Powers et al., 2015).[3] Following common practice, I will also use trope (from the Yiddish trop) to refer to the different modes used for the reading of specific Biblical texts in liturgical contexts, as in “Haftarah trope” (the mode of Haftarah reading) or “Torah trope” (the mode of Torah reading). The six sets of melodies are used as follows: (1) one for Torah readings on a normal Sabbath (also for weekdays and festivals); (2) one for Torah readings on the High Holidays (the mornings of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur); (3) one for Haftarah readings (selections from the prophets); (4) one for Lamentations, read on Tisha B’av; (5) one for the book of Esther, read on Purim; and (6) one for the festive megillot—Song of Songs, Ruth, and Ecclesiastes—read on Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot respectively.[4]

The word ta’am (plural te’amim) refers to a Biblical accent mark, but it also means “flavor,” “taste,” and “sense,” or “reason” (Jacobson 2002, 3; Kogut 1994, 13; Portnoy and Wolff 2001, 6). The present analysis opens the musical “flavor” or “taste” of the te’amim for study, alongside their text-phrasing functions. We will find that the Haftarah and High Holiday melodies have features in common, including the scale and focal pitches, but whereas Haftarah trope reaches upward with gestures of yearning, High Holiday trope remains more “grounded,” with a reciting tone (a repeating and returning pitch) on the tonic or final of the mode. A shift of tonal center at the end of each verse in the High Holiday melodies, however, mirrors the inner transformation sought through prayer and t’shuvah (repentance) during this liturgical occasion. We will find a form of tonal collapse in the Lamentations mode, appropriate for the lament of the text, and an unusual degree of mobility in the melodies of Esther, which correlates nicely with the dynamic story and transgressive traditions of Purim. We will find that the modes for Torah readings and for the Song of Songs, Ruth, and Ecclesiastes both use a major scale, but the focal pitches and collections within the scale are markedly different. Torah cantillation may be heard as normative since it is heard throughout the year; in comparison, festive megillot trope may be heard as marked and special.

The focus on the musical aspect of cantillation may seem antithetical to the kind of fusion of melody and speech that Judit Frigyesi describes in traditional Eastern Ashkenazi contexts. As Frigyesi observes, “Melody is not an additional element, but part and parcel of the text, inseparable from it and inconceivable without it, and vice versa: text is inconceivable without its melody” (2000, abstract). And yet, the idea of a fusion of text and music is itself strategic and context dependent.[5] Frigyesi also observes that melody may serve the purpose “of establishing an aural-spatial context for religious performance, inspiring and expressing a state of religious spirituality” (2000, 14). The present analysis seeks to delineate the nature of this “aural-spatial context,” and the way it varies with liturgical occasion and reading.[6]

In Section 2 below, I introduce the te’amim and their text-parsing functions. This will serve as an introduction for those who are not familiar with the practice of Jewish cantillation. In Section 3, I present the melodies of Haftarah cantillation along with issues of notation and transcription, drawing on a recording by Cantor Pinchas Spiro. Section 4 addresses variability within the Eastern Ashkenazi tradition. Sections 5–9 present additional modes, one at a time; a set of common phrases facilitates comparison between the modes. Paired comparisons are especially revealing; they show commonalities, which in turn bring differences and unique features of each mode into relief. Section 10 explores a single phrase across the six modes, and it corroborates ideas introduced earlier about the expressive qualities of the modes. Section 11 deepens the analysis with a consideration of one additional phrase and the melodies for ends of sections, in all six modes. Cantor Elizabeth Sacks of Temple Emanuel, Denver, recorded the notated examples in Sections 4–11; the audio is included with each example.[7] I conclude in Section 12 by reflecting on the goal of this work—which is to offer new ways of hearing and understanding cantillation—in the context of prior work in music theory and future work in the study of Jewish music.

The Te’amim and Text-Phrasing

The te’amim in use today were developed and notated by generations of Masoretic scholars in Tiberias, leading up to the tenth century C.E. (Khan 2012, 1–2). The melodies of biblical cantillation are typically learned first with the te’amim and their names. The te’amim of the Tiberian system, which are given above or below each word in a printed Hebrew Bible, serve three functions: they indicate the accented syllable (phonology), the phrasing of the text (prosody), and the melodic motif for each word. Some of the Tiberian te’amim are conjunctive, indicating a text-phrase that continues onward, and some are disjunctive, indicating the end of a text-phrase. The disjunctive te’amim divide each verse once, then again, and again—with up to four levels, depending on the length and complexity of the verse (Dresher 1994, 2013; Jacobson 2002 and 2013; Kogut 1994, 18–27).[8] The phrasing and accentuation of the text of course affects meaning, as almost all commentators have noted. Zekharyah Goren (1995) explores this aspect of the te’amim in depth, and Simcha Kogut (1994) investigates the relationship between the phrasing of the te’amim and the exegesis in Rabbinic sources, Aramaic translations, and medieval Jewish commentaries (see also Cohen 1972, Khan 2000, and Strauss Sherebrin 2013).

Example 1 provides a relatively simple verse from Isaiah (40:27); this is the beginning of the Haftarah for the parashah (weekly Torah reading) “lekh l’kha.” I have provided the Hebrew with te’amim (Example 1a), and an English transliteration with te’amim and translation (Example 1b).[9] Some of the te’amim in the transliteration are flipped on a vertical axis so that they match the left-to-right direction of the transliteration. For example, in the last line of the verse, the ta’am (accent mark) under “u-mei-elohai” is a tipḥa, which is a disjunctive. The shape of the ta’am shows that it marks the end of a phrase: it is closed to the right in the transliteration and closed to the left in the Hebrew.

Example 1a. Isaiah 40:27: Hebrew text with te’amim

Example 1b. Isaiah 40:27: Transliteration with te’amim and translation

The basic phrasing and structure of this verse is readily apparent: it divides in half, and each half consists of two parallel statements. Thus, we can also represent the verse as follows: “lamah tomar ya-akov / u-t’daber isra-el // nist’rah darki mei-adonai / u-mei-elohai mishpati ya-avor” (Why do you say, Jacob / Why declare, Israel // My way is hid from the Lord / And by my God my cause is ignored).[10] Example 1b arranges the verse in four lines to show the parallelism and main divisions.

We can use this verse to identify and understand the most common te’amim. Etnaḥta, the fish-bone shaped ta’am at the end of line two, marks the main division of the verse. Sof pasuk or siluk, the vertical line at the end of line four, marks the end of the verse. (The terms sof pasuk and siluk are interchangeable; both refer to the end-of-verse ta’am.) Formally, we can label etnaḥta and sof pasuk as “D1”; the “D” stands for disjunctive and the “1” indicates that they are level-one disjunctives (at the highest level). We can specify further that sof pasuk is a “D1f” ta’am; it marks the end of the final phrase at level one.[11]

Table 1 provides all the te’amim in this verse with their functions, along with one additional ta’am that appears frequently but is not present in this verse (munaḥ). The te’amim are organized by level, from highest to lowest disjunctives, with three conjunctives at the bottom. Etnaḥta and sof-pasuk are in rows one and two. The third row gives zakef katon (or more simply, katon), a level-two disjunctive; this marks the ends of lines 1 and 3 in Example 1b. Tipḥa, in the fourth row, is the final level-two disjunctive; this marks an internal division within lines 2 and 4 of Example 1b. Pashta in the fifth row is a level-three disjunctive, and it marks an internal division within lines 1 and 3 of Example 1b. The te’amim in rows six and seven are the two conjunctives in this verse. Mapakh “serves” (i.e., comes before) pashta; see lines 1 and 3 of the verse. Merkha “serves” (i.e., comes before) sof pasuk; see line 4 of the verse. (Merkha also commonly serves tipḥa.) Finally, munaḥ is a common conjunctive that happens not to be in this verse; munaḥ serves etnaḥta, zakef katon, and other disjunctives.

Table 1. Te’amim in Isaiah 40:27 (and one additional ta’am) with text-phrasing functions

The eight te’amim in Table 1 are a small selection; there are twenty-seven te’amim in all. But these eight are the most common ones, and the most significant for text phrasing. Jacobson (2002, 412) provides a chart that indicates the frequency of the te’amim throughout the twenty-one prose books of the Hebrew Bible (all except for Job, Proverbs, and Psalms).[12] The five disjunctives in Table 1 account for 79% of the disjunctive te’amim, and the three conjunctives in Table 1 account for 86% of the conjunctives.

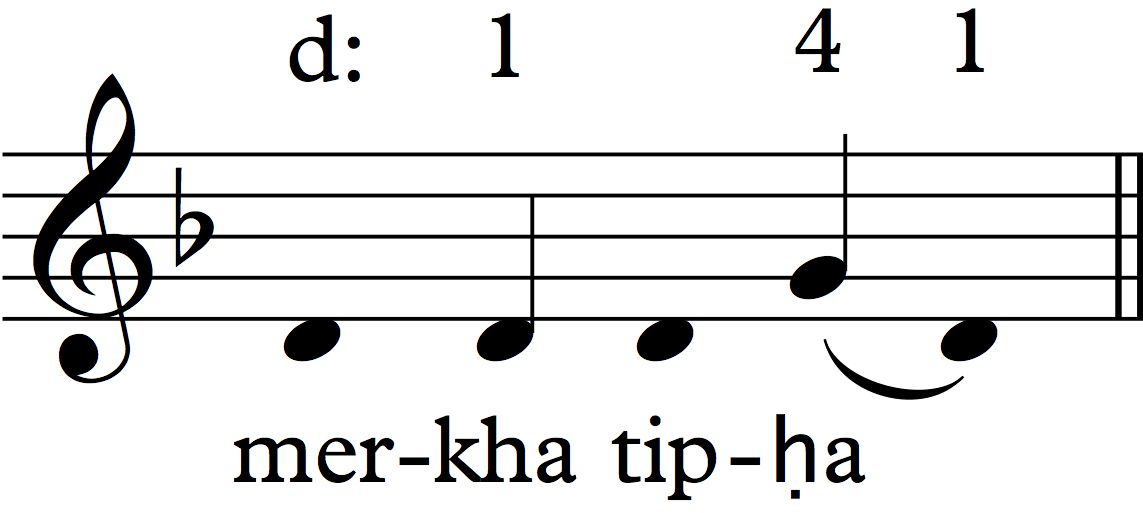

The te’amim are often taught in phrases, with conjunctives and disjunctives combined. Thus, for instance, one might begin learning to chant with merkha-tipḥa munaḥ-etnaḥta. But one would then practice each phrase in a variety of forms, to prepare for the way the phrases appear in the Biblical verses (see Binder 1959; Cohen 2003–8; Jacobson 2002; and Portnoy and Wolff 2000 and 2001). Table 2 provides four versions of the etnaḥta phrase (i.e., the phrase that ends in etnaḥta). Note that the disjunctives are always present—as long as there is a division at the given level.[13]

Table 2. Versions of the phrase that ends in etnaḥta

There is one further nuance that needs to be introduced here: the final disjunctive at a given level is not generally the strongest one.[14] For instance, in Example 1b katon (D2) marks the ends of the lines, but tipḥa (D2f) marks divisions within the lines. This can be understood in terms of the logic of recursive dichotomy.[15] Example 2a shows the first half of Isaiah 40:27 with etnaḥta at the end and katon in the middle. The brackets show that the level-two katon phrase divides the level-one etnaḥta phrase.

Example 2a. Recursive dichotomy in the first half of Isaiah 40:27: First division

Example 2b then shows another step in the recursive dichotomy; tipḥa divides the phrase “u-t’daber / isra-el.” But since this ends with a level-one etnaḥta, the disjunctive tipḥa is again considered a level-two disjunctive. The height of the brackets nonetheless shows that katon (D2) is a more significant level-two disjunctive than tipḥa (D2f).[16]

Example 2b. Recursive dichotomy in the first half of Isaiah 40:27: Second division

Finally, Example 2c shows the division of the first part, “lama tomar / ya’akov,” with pashta. Pashta divides a level-two phrase, and so it is a level-three disjunctive. Thus, when katon (D2) and tipḥa (D2f) occur in succession, katon marks the more significant division. In some cases, tipḥa occurs without katon; then tipḥa on its own marks the only significant second-level division.[17]

Example 2c. Recursive dichotomy in the first half of Isaiah 40:27: Complete division

The Melodies of the Cantillation (Haftarah Trope) and Issues of Notation

Now we can begin to consider the melodies in connection with the te’amim and their text-parsing functions. Example 3 provides a recording of Isaiah 40:27 chanted by Cantor Pinchas Spiro, with a transcription.[18] Barlines in the transcription indicate phrase boundaries, not musical meter. Some regularity may be heard in Spiro’s recording, but Jewish cantillation does not generally have a regular beat or meter (Jacobson 2002, 14). Double barlines indicate the ends of level-one phrases associated with etnaḥta and sof pasuk, single barlines indicate the ends of the main level-two phrases associated with zakef katon.[19] Stemmed pitches set accented syllables in the text.[20] In Hebrew Bibles, most of the te’amim are placed above or below the accented syllable of the word—in fact one of the purposes of the te’amim is to indicate which syllable should be accented.[21] Along with this, the alignment of melody and syllabic accent is generally specified in pedagogy (both oral and notated). The te’amim themselves are given above and below the staff in Example 3. Slurs in the notation indicate melismas; there are brief two-note melismas at the end of many words and an extended melisma on “isra-el.”

Example 3. Isaiah 4:27 transcription and recording

In this recording, Cantor Spiro chants the verse with D as tonic or “final.” The precise pitch level is not significant, however; readers may chant at any level that is comfortable for their voice. The type of scale and scale degree will be more important for analysis. This verse—and Haftarah trope in general—emphasizes scale degrees 1, 3, and 4 in the minor scale. We may notice, for instance, the 4-1 (G-D) skips on “lamah” and “nist’rah,” the phrase endings on 3 and 4 (F and G), and the verse ending on 1 (D).[22]

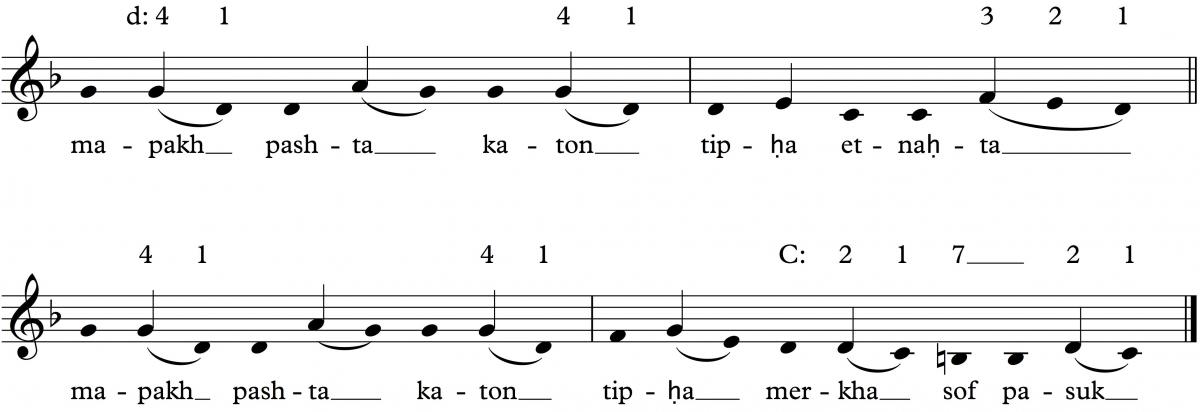

Example 4 provides an analogue for the transcription in Example 3 with names of the te’amim in place of the words.[23] (A reader may sing the melody with the names of the te’amim before applying it to the verse.) The te’amim themselves are also given above and below the staff, and selected scale-degrees are given above.

Example 4. Te’amim for Isaiah 40:27 with Spiro’s haftarah melodies

We can use Example 4 to explore further properties of the mode. We can notice, for instance, that the ending on 3 occurs with katon (D2), that etnaḥta (D1) has the distinctive <1-3-5-4> melisma, and that sof pasuk (D1f) is the only disjunctive ta’am to end on 1. We may also note that the verse uses the minor pentatonic exclusively: 1, 3, 4, 5, and 7. Verses with additional te’amim include 2 and 6, but the minor pentatonic collection remains primary.[24] Finally, there is a kind of “buoyancy” to the melodies; they touch down on the tonic—scale-degree 1—but ascend repeatedly from there. These are some of the musical elements that project the parsing of the text, in Haftarah cantillation; they are also some of the elements that give Haftarah trope its particular sound or “flavor” (ta’am).

Variants and Sources

Example 5 provides the same te’amim as in Example 4 with slightly varied melodies, based on the notation in Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 45). The text underlay for etnaḥta is different: Spiro sings it with the accented syllable on the 1 (D) and a four-note melisma (Example 4); Kalib’s version is more syllabic, with the accented syllable on 5 (A) and a two-note melisma (Example 5). (In my text analysis, I use dashes for pitches connected by melismas and commas for pitches set syllabically; Spiro’s etnaḥta is thus <1-3-5-4> and Kalib’s is <1, 3, 5-4>.) The melody itself is also different at the end of the verse: Spiro approaches the tonic (D) from 7 (C) below; Kalib approaches it with a descending <5, 3-1> arpeggio. Each ending has a distinctive flavor and musical sense. The descending arpeggio in Kalib’s version (Example 5) balances the ascending arpeggio of etnaḥta. Spiro’s version (Example 4) creates closure by bringing in the note below the tonic, for the first and only time in the verse.

Example 5. Te’amim for Isaiah 40:27 with melodies based on Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 45)

These types of differences are common.[25] There is no single authoritative source for the melodies of Jewish cantillation, even within the Eastern Ashkenazi tradition. Individual notated and/or recorded versions derive authority from the people who produce them, from the lineage of teachers and sources, and from their publication and distribution. For example, the melodies notated by Portnoy and Wolff (2000 and 2001) are grounded in older notations by Abraham Binder (1959) and Cantor Lawrence Avery (unpublished), and they are published and distributed by URJ Press. Sholom Kalib’s notation is based on a deep grounding in tradition in his own family of immigrants from Western Ukraine, close contact with leading cantors in the West Side of Chicago beginning in the 1940s, and additional fieldwork in the late 1970s (Kalib 2002; vol. 1, part 1, xi–xii). Other sources are authoritative for other reasons, within individual communities and denominations.[26]

One might choose and focus on a single source, for analysis. That would simplify matters, but it would not reflect the variability of practice within the Eastern Ashkenazi tradition. One might, alternatively, study the variability itself, but that would make it harder to get an overall sense for the important musical features of each of the modes.[27] I will take a middle road: I will work with variants, but I will not focus on the variability as such. In practical terms, I will present individual recorded and notated examples for analysis, acknowledging the source in each case, and I will comment on some of the more significant variations along the way. The sources consulted are Binder 1959, Cohen 2003–8, Jacobson 2002, Kalib 2002, Ne’eman 1954, Ne’eman 2012, Portnoy and Wolff 2000 and 2001, Slobin 1984–86, and Spiro 1994.[28]

This approach is both in tension and aligned with practice. In my experience, some communities aim for uniformity of practice; this is especially the case when a new group of readers are being trained. Other communities welcome readers with differing melodies.[29] Some individual readers, especially those who are more advanced, bring a certain (albeit limited) amount of improvisation into their practice.[30] The analysis here allows for this kind of variability in practice; it does not canonize a single source, and it takes variants within the Eastern Ashkenazi tradition into account.[31]

Comparison of Haftarah and High-Holiday Modes

The High Holiday cantillation mode is similar to the Haftarah mode in many ways; a comparison of the two will illustrate the similarities while also setting them in relief. The Haftarah melodies are more “buoyant,” as mentioned above; the High Holiday melodies are more grounded, and perhaps more somber—until the end of the verse, where there is a shift of tonal center.

Example 6 provides the same set of te’amim as in Examples 4 and 5 above (from Isaiah 40:27) with Haftarah melodies above (6a) and High Holiday melodies below (6b).[32] Both melodies are based on Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 44 and 45).[33] The first phrase is almost identical; the Haftarah and High Holiday melodies both begin with a descent from 4 to 1 and a return to 4 via its upper neighbor. But whereas the first Haftarah phrase ends on 3 (F), the first High Holiday phrase returns to 1 (D). At the end of the second phrase, on etnaḥta, the distinctive <1, 3, 5-4> of Haftarah trope is replaced by a <3-2-1> descent in High Holiday trope. The High Holiday <3-2-1> etnaḥta is melismatic, with the accented syllable on 3; it is a distinctive feature of High Holiday trope, and it gives the mode a plaintive quality.[34] The third phrase has the same te’amim as the first—in this particular set of phrases from Isaiah 40:27. The modes are similar thus far, but the first three Haftarah phrases remain suspended on 4 and 3, while the High Holiday phrases return to 1.

Example 6a. Haftarah and High Holiday cantillation based on Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 44): Haftarah melodies

Example 6b. Haftarah and High Holiday cantillation based on Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 45): High-holiday melodies

The fourth Haftarah phrase finally ends on 1 (D), confirming the tonic, but the fourth High Holiday phrase ends on C, a whole step below the tonic. We may hear this C as a new tonic—we may hear a shift of tonal center. C is the pitch of arrival, at the end of the verse, and it is approached from above and below. In more general terms, we can say that the High Holiday phrases are in minor, with phrases that repeatedly end on 1 of the minor scale, but the final phrase settles onto a major scale with the final one whole step below.[35] (The terms “minor” and “major” should be taken here simply to reference the use of minor and major scales, or significant portion thereof, with the bottom note as tonic or final.) Each succeeding verse begins back up a whole step in minor.[36]

We can think of and hear the shift of pitch center as a transformation, analogous to the personal and communal transformation sought during the High Holidays. And to the extent that the “settling down” on the new final is a kind of softening, one may hear forgiveness or t’shuva (repentance, return) in the melodies, enacted within each verse. Associations of the major scale could play into this as well, for some listeners and readers, although these associations are not stable in Jewish music. In a similar way, one may hear qualities of both darkness and yearning in the haftarah mode; darkness because of the minor scale and yearning because of the rising gestures. These qualities are consistent with the affect of many of the texts from the Prophets. In the verse under consideration here, for instance, the people of Israel feel that God is distant; they lament this distance and presumably yearn for a closer connection (see Example 1).

Comparison of Lamentations and High-Holiday Modes

There is also a tonal shift in the Lamentations mode, but in this case it is from major to minor. Example 7 provides our basic set of phrases with Lamentations melodies in a variant from Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 49). Annotations above the melodies suggest that the first and third phrases may be heard in F major (i.e., with a major scale built on F), and the second and fourth phrases may be heard in D minor (i.e., with a minor scale built on D). The sense of F major is projected in phrases one and three by the emphasis on C and F, with the C-F descent of katon; D minor is projected in phrases two and four by the ordered scalar descent,

Example 7. Lamentations cantillation based on Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 49)

The etnaḥta of Lamentations trope features the same plaintive <3-2-1> figure that we found in the etnaḥta of High Holiday trope, but Lamentations trope replicates this figure four-fold. The sof pasuk of Lamentations trope repeats the <3-2-1> descent; we thus get it at the main division and the end of each verse. And the tipḥa of Lamentations trope reproduces the figure in transposition, as <6-5-4>. (The intervallic pattern of <6-5-4> matches the intervallic pattern of <3-2-1> precisely; both move down by half and then whole step.) Thus, we get the figure twice as <6-5-4> and twice as <3-2-1>—in this set of phrases as in many of the verses from Lamentations.

Example 8 provides notation for Lamentations I:1—a verse that includes the basic phrases of Example 7 along with additional te’amim and their melodies. Annotations above the music notation show scale degrees in F major and D minor. Double barlines show the etnaḥta and sof pasuk phrase endings, single barlines show the katon endings, and dotted barlines show further divisions. In this particular case, the repetition of melodies for the etnaḥta and sof pasuk phrase endings reflect a parallelism in the text; compare “haitah k’almanah” and “haitah lamas” before the two double bars.[39]

Example 8. Lamentations 1:1

Recall again the motivic link between Lamentations trope and High Holiday trope, the plaintive <3-2-1> figure. Lamentations trope is suffused with this figure, as we have seen. High Holiday trope returns to this figure seven weeks later and redeems it, as it were. We get the minor <3-2-1> on etnaḥta, on the first day of Rosh Hashanah; the sof pasuk of each verse then settles onto the new tonic one whole step below. The period from Tisha B’av to Rosh Hashanah is a period of consolation in the Jewish calendar—seven “Haftarot of consolation” are read on the Sabbaths between the two holidays. The melodies of Lamentations cantillation can be heard to lead to the melodies of High Holiday cantillation just as the despair of Tisha B’Av leads to the renewal of Rosh Hashanah.

Esther and Lamentations Modes: Celebration and Mourning

The modes for Esther and Lamentations have a number of similarities, which may seem surprising since the holidays of Purim (when Esther is read) and Tisha B’Av (when Lamentations is read) are very different in character, at least on the surface. Purim is a holiday of raucous celebration; Tisha B’Av is a day of deep mourning. There are also differences in the modes, though—each mode is distinct—and the melodies accrue different associations. One of the differences has to do with the style of reading: Esther is often read fast and loud; Lamentations is read much slower and in a softer voice. Other differences have to do with melodic features, which I will outline below.

As with our other paired modes, the musical similarities encourage comparison, and the comparison in turn brings unique aspects of each mode into relief. A comparison between Lamentations and Esther trope is also interesting because we hear them in immediate succession. Verses from Esther that deal with topics of sadness and mourning are commonly read in Lamentations trope (see Jacobson 2002, 831–32 and Summit 2000, 133–34). In other words, the reader switches from Esther trope to Lamentations trope and back, and the congregation hears this switch at the verses of mourning.

Esther trope features the same move from relative major to relative minor as in Lamentations trope, but there are ambiguities in Esther trope; the two pitch centers are not as clearly established and the switch is not as stark. Example 9 provides our basic phrases in Esther trope in a variant from Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 47–48) and Portnoy and Wolff 2001 (89). The opening mapakh pashta ascends through the F major triad. But whereas Lamentations trope arrives on F for katon, at the end of the first phrase (see Example 7), Esther trope presents a more ambiguous G-E figure for katon (see Example 9). One may hear the G-E of katon in Esther trope as 2-7 in F major, outlining part of a dominant triad in F.[40] One may also hear it as part of a transition (like a pivot chord), leading into the new key. The etnaḥta phrase in Example 9 moves clearly into D minor.

Example 9. Esther cantillation based on Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 47–48)

So far, we have a move from a final on F (tonic of a major scale) to a final of D (tonic of the relative minor scale), but F as a pitch center is not as clearly established as in Lamentations trope. The final phrase in Example 9 also destabilizes D as a final pitch or resting place. The melody of tipḥa in this final phrase descends from A to D, but the final phrase arrives on G, not D. The

The Torah Mode

The Torah mode surrounds its final with pitches a fifth above and fourth below, and the final here is the tonic of a major scale. There is also a recurrent resting point on the 2, the note above the final. Examples 10a and 10b provide two variants of our basic phrases from Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 43) and Portnoy and Wolff (2000). I will consider Example 10a first, and then discuss the differences in Example 10b.

The first phrase of Example 10a emphasizes 5 and 1; katon at the end of the first phrase then settles on 2. The second phrase begins and ends on 2, touching down on the 5 below. There is also neighbor-note motion on tipḥa, <2, 3-2>—which recalls and reiterates the <3-2> motion at the end of the first phrase. The final sof pasuk phrase answers the etnaḥta phrase by settling down on 1. The <3-1> ending of sof pasuk also recalls the earlier <3-2> of katon (end of phrases one and three) and effects a structural resolution of 2 to 1.[44]

Example 10a. Torah cantillation. Melodies from Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 43)

The melodies are varied in Example 10b, but much of the outline remains the same.[45] The first phrase still features the upper scale-degree 5 and descends to 2; the second phrase still begins and ends on 2.[46] There is an embellishment of tipḥa in the second phrase, which makes it slightly more ornate but does not otherwise affect the melodic or tonal implications. The most significant difference is at the end of the verse: sof pasuk in Example 10b ends with a 1 to 5 descent in place of 3 to 1.[47]

Example 10b. Torah cantillation. Melodies from Portnoy and Wolff 2000

The Festive-Megillot Mode

The festive-megillot mode focuses on 3 of a major scale, settling down to 1 only at the end of the verse. The shifting tonal contexts for 3 create beautiful ambiguity and a bittersweet aura. Example 11 provides the basic phrases in a version from Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 50). The first phrase moves in an axis between 3 (E) and 6 (A), with 7 (B) as an upper neighbor and 5 (G) as an intermediary pitch. There is no upper tonic in these phrases; the leading tone remains unresolved. One might also hear a temporary centricity on 3 (E), and there is a brief ascending E minor triad on pashta.

Example 11. Festive-megillot cantillation based on Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 50)

A comparison between the festive-megillot and High Holiday modes is instructive. Both have phrases in minor, which then settle onto major scales at a lower level. In High Holiday trope, there is motion down by step—we can represent the scales as ii (minor) to I (major); in festive megillot trope, there is motion down by third—we can represent the scales as iii (minor) to I (major).[48] The special effect of iii in relation to I is evident from the way the leading tone (the fifth of iii) does not resolve. Other variants of the festive megillot mode include half-step motion from F to E, which creates the temporary effect of a Phrygian mode on E (see Portnoy and Wolff 2001, 91–93; Binder 1959, 117–22).

Phrases two and four of Example 11—the etnaḥta and sof pasuk phrases—move into C major, but the cantillation continues to hover on E (3), settling onto C only at sof pasuk. The etnaḥta phrase begins on E and ends on E; tipḥa on its own also begins and ends on E. The effect is not the same as an imperfect authentic cadence (IAC) because there is no dominant-to-tonic motion; instead, E is simply recontextualized with C below and G above. We can compare this with the tonal shifts in Lamentations trope—which occur at the same places (see Example 7). Lamentations trope moves from III to i; the festive megillot trope moves from iii to I. But in Lamentations the move into minor is scalar and clearly directed. In the festive-megillot mode it seems almost happenstance—the shift is more subtle since E (3) remains present as a focal pitch.

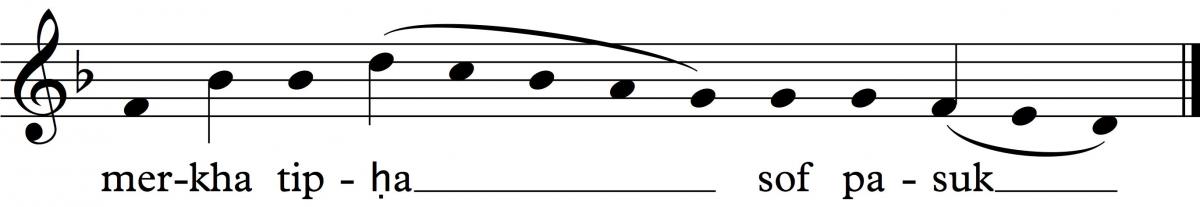

The Merkha-Tipḥa Phrase in Six Modes

Thus far, I have introduced significant musical and expressive features of the modes by comparing them in pairs with a set of basic phrases. Phrases from this basic set—which is derived from Isaiah 40:27—can be found in all Biblical verses; they are some of the most common phrases. We can get a different view, a cross section of Eastern Ashkenazi cantillation, by considering a single phrase in the six modes. The merkha-tipḥa phrase is one of the most common, and it is a phrase that readers often begin with when learning to chant. (I use the term “phrase” here, as in Section 2 and 3 above, to refer to any frequently found combination of te’amim that ends with a disjunctive. Merkha-tipḥa is a level-two phrase, which occurs within higher-level etnaḥta and sof-pasuk phrases.) Tipḥa is a level-two disjunctive (D2f), and merkha is a conjunctive.[49] The study of this phrase will reinforce my interpretations of the “ta’am” (flavor) of individual modes and their connections with texts and liturgical occasions.

Example 12 provides the merkha tipḥa phrase in all six modes.[50] A common pattern or “schema” can be seen in Examples 12a–d: merkha sets up a recitation tone; tipḥa begins on the recitation tone, ascends on the accented syllable, and returns to the recitation tone.[51] Annotations show the key and scale degree of the recitation tones in each mode. The examples are also arranged to show other connections: 12a and b are in major with a lower note as a pickup; 12c and d are in minor with the recitation tone itself as the first pitch. The High Holiday phrase (12c) is the only one with a recitation tone on 1; the mode is “grounded” on the tonic as noted above.

Examples 12e and f, from the Haftarah and Lamentations modes, do not match the schema of the other modes. The Haftarah version (12e) moves up and does not return; the overall trajectory is from 1 (D) to 4 (G). This correlates well with my analysis of Haftarah trope above: the rising tendencies or “buoyancy” of Haftarah trope seems to trump participation in the merkha tipḥa schema of the other modes.[52] In the Lamentations version (12f), there is no recitation tone; the phrase leaps up and then descends with the <6-5-4> figure. This correlates well with my analysis of Lamentations trope above: the descending lament trumps participation in the regular schema.

(a) Torah

(b) Festive megillot

(c) High Holiday

(d) Esther

(e) Haftarah

(f) Lamentations

Example 12. The merkha-tipḥa phrase in the six modes

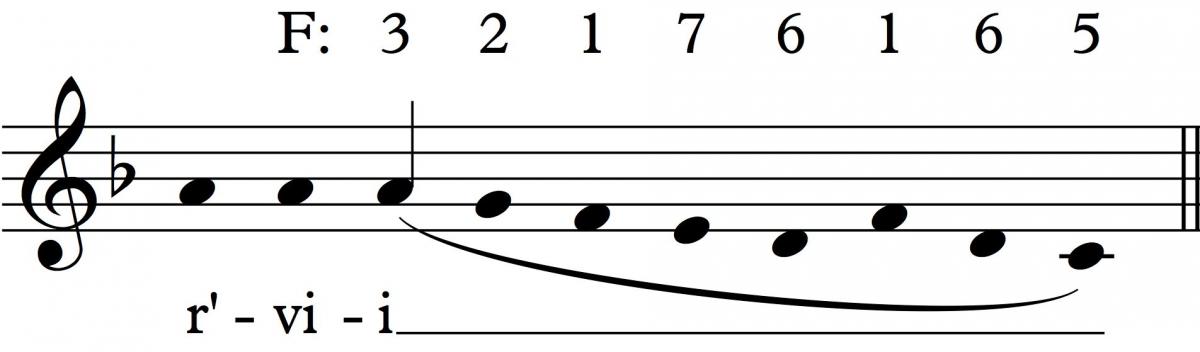

The R’vi-i Phrase and Special Melodies for the End of a Section

We can also deepen our understanding of the modes by considering two additional phrases: the r’vi-i phrase and special melodies for the end of a section or chapter. R’vi-i is a level-three disjunctive, and it is the next most common disjunctive after the ones listed in Table 1.[53] The special melodies for the ends of sections are applied to the sof pasuk (end-of-verse) phrase—in the final verse of a section or chapter.[54] In some cases, the r’vi-i and end-of-section melodies provide additional tonal contrast; in other cases they reinforce contrasts that are already present in the basic phrases considered above.

Example 13 provides the Torah-trope melodies for a set of phrases with r’vi-i.[55] R’vi-i at the beginning descends from 3 to 6, creating the effect of a temporary move to vi (D minor). R’vi-i thus adds an element of tonal contrast; there are no other disjunctives that end on 6 in the Torah mode. But the relative-minor implication of r’vi-i does anticipate the melody used for the ends of sections in Torah trope. (I provide notation for the end-of-section melodies below.)

Example 13. Sample phrases with r’vi-i in Torah trope. Te’amim based on Genesis 21:7.

The phrases in Example 13 derive from Genesis 21:7, which relates Sarah’s amazement at the birth of Isaac. This verse is also chanted with High Holiday trope on the first day of Rosh Hashanah. Example 14 provides notation for the same te’amim in the High Holiday mode. Here, the melody of r’vi-i anticipates the ending of the verse in C major. Thus, in High Holiday verses that include r’vi-i, there is an initial hint of C major, then a set of phrases in D minor with the distinctive <3-2-1> of high holiday trope, and then the arrival on C major with sof pasuk.

Example 14. Sample phrases with r’vi-i in High Holiday trope. Te’amim based on Genesis 21:7.

Example 15 provides the r’vi-i melody in all six modes.[56] R’vi-i in general moves down in a scalar pattern, sometimes with an extra jog at the end. In High Holiday trope (15b), the extra jog emphasizes the arrival on C. In Lamentations and Esther trope (15c and d), I interpret the final note of r’vi-i as 5 in F major; phrases that follow r’vi-i in both cases project F major. The r’vi-i melody in the festive-megillot mode (15f) is the only one that ends with a stepwise ascent instead of a descent—it does so to avoid C and return to the E (3), at the last moment.

(a) Haftarah

(b) High Holiday

(c) Lamentations

(d) Esther

(e) Torah

(f) Festive megillot

Example 15. R’vi-i in the six modes

Table 3 summarizes the tonal implications of r’vi-i in the order of Example 15 and the presentation above (sections 3 and 5–9). The pitches in parentheses indicate pitch centers in the notation of this paper; “minor” and “major” refer to the use of minor and major scales built from these pitch centers. Roman Numerals show relationships between the pitch centers and their associated scales more generally (they do not reference harmony).[57] Table 3 shows that the tonal contrast of r’vi-i in the Torah mode (moving to vi) is unique; in the other modes, r’vi-i aligns tonally with other phrases. The effect of anticipation in the High Holiday mode is also unique; r’vi-i anticipates the arrival on C or I at the end of the verse. In the remaining modes, r’vi-i concludes on a pitch associated with earlier phrases. The overall diversity of effect is typical: all the modes have some element of tonal contrast, but individual te’amim participate in that tonal contrast in a variety of ways.

Table 3. Tonal implications of r’vi-i

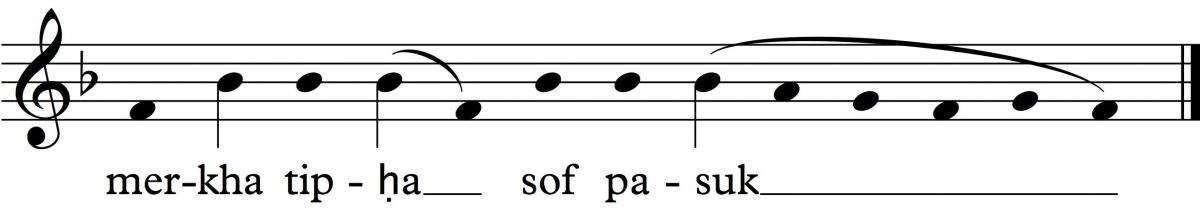

Example 16 provides end-of-section phrases for all six modes.[58] These are ornate melodies; the extra melodic flourishes create effects of closure and conclusion. Tonal effects, which are summarized in Table 4, are of two kinds. In the Haftarah and Torah modes, the end-of-section melodies establish new pitch centers, not present (or not strongly present) in the remainder of the mode. These two modes in fact are inverses of each other: the end-of-section melodies for Torah readings cadence on the relative minor (vi); end-of-section melodies for Haftarah readings cadence on the relative major (III). These shifts in turn provide tonal links to the blessings recited by the reader after the Haftarah and Torah readings (see Tarsi 2001, 158). The end-of-section melodies in the remainder of the modes (High Holiday, Lamentations, Esther, and festive-megillot) cadence on the same pitch and in the same key as the regular end-of-verse (sof pasuk).

(a) Haftarah

(b) High Holiday

(c) Lamentations

(d) Esther

(e) Torah

(f) Festive megillot

Example 16. End-of-section melodies in the six modes

Table 4. Tonal implications of end-of-section melodies

Conclusion

This study has focused on ways of hearing and ways of understanding the music of Jewish Biblical cantillation in the Eastern Ashkenazi tradition. The approach has been comparative within the tradition, bringing pairs of modes together in order to set them apart. When I reflect, now, on the melodies of Haftarah and High Holiday cantillation, I am immediately aware of the musical links—the focus on scale degrees 1 and 4 in a minor scale, with 5 as an upper neighbor to 4. And with these links in mind, I am aware of the differences that give each mode its individual ta’am or flavor—the buoyancy of Haftarah trope, and the “groundedness” of High Holiday trope, focusing on 1 with a shift of tonal center at the end of each verse. The musical aspects of the individual modes come into focus, as it were, along with their function in the liturgy.

The goal of the analysis is thus not to make any claims about historical authenticity, nor to differentiate Eastern Ashkenazi cantillation from other traditions, nor to link it with other domains of Jewish music (e.g., the prayer modes). Rather, the goal is to increase our understanding of this musical system. In this way, it is aligned with the commonly stated goal of music analysis; as David Lewin puts it, “whatever the use to which the analysis is put (theoretical, historical, the acquisition of compositional craft, aid in preparing a performance), its goal is simply to hear the piece better, both in detail and in the large” (1969, 63; italics in the original).[59]

There are many different ways to hear a piece—or a cantillation mode—better, and the analysis is therefore open ended.[60] One might continue the present analysis by exploring the correlation between melody and text structures in greater detail. The principle of recursive dichotomy, which generates the te’amim, has been studied in detail—but the resultant correlations of text and music are open for further investigation. In the Haftarah mode, for instance, we observed that there is an arrival on 3 with the second level disjunctive zakef katon, and in Isaiah 4:27 this arrival correlates with the ends of the syntactic clauses “lamah tomar ya-akov” and “nist’rah darki mei-adonai” (see Examples 1 and 3 above). But in other verses, the recursive dichotomy places zakef katon—and the arrival on 3—within individual syntactic clauses. Effects of musical parallelism in individual modes may also be explored, along with textural parallelisms; sometimes the musical and textual parallelisms align and sometimes they do not. Finally, we may listen for and assess effects of timing, dynamics, and vocal quality in the reading of individuals as they present Biblical passages with the system of cantillation.

The approach taken here, with a combination of close analysis and interpretation, is also relevant to other traditions and genres of Jewish music, both liturgical and non-liturgical. The analytical study of Jewish music in that sense is an open field. It may be developed as music theorists continue to explore genres outside of the Western classical canon (see Tenzer 2006, Tenzer and Roeder 2011, and the journal Analytical Studies of World Music) and as scholars of Jewish music explore musical perceptions and understandings in deep, open, and dialogical ways.

Audio example 3 sung by Cantor Pinchas Spiro. All other audio examples sung by Cantor Elizabeth Sacks.

Endnotes

[1] Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the First International Conference on Analytical Approaches to World Music (Amherst, 2010) and the annual meeting of the Society for Ethnomusicology (New Orleans, 2012). I would like to thank Mark Slobin, Elias Sacks, and Edwin Seroussi for comments on earlier drafts.

[2] The goals of prior analytical work on Jewish cantillation have primarily been to document and delineate traditions (Kalib 2002), compare traditions and find a unifying essence (Idelsohn [1929] 1944; Hitin-Mashiah and Sharvit 2013), reconstruct original practice by deductive methods (Weil 1995), and trace historical continuities and discontinuities (Avenary 1978). In comparison, the present paper explores current practice within a single tradition. The extensive analysis by Ne’eman (1954–71) forms a significant precedent for this article, but Ne’eman does not engage in the kind of comparative study of modes that I propose here. Rosowsky (1957) explores rhythmic aspects of cantillation, focusing on one of the modes; the rhythmic theory is detailed and precise but it does not reflect the variability of practice. Rosowsky also provides a pentatonic theory for the melodies for Torah readings (1957, 477–517). Schönberg 1927 provides a condensed and rich analysis of German-Jewish (Western Ashkenazi) cantillation based on notation in Baer (1883) 1953. Schönberg’s impressionistic observations about beginning, preparation, and closing motives anticipate some aspects of the present approach, as do his observations about contour (1927, 22–29). For a broad perspective on the institutions, personalities, and resources that have shaped Jewish music study in the United States, see Cohen 2008. Critical perspectives on Idelsohn’s project and the study of cantillation can be found in Seroussi 2009, 24-26 and 47-48. Seroussi observes, for instance, that the study of cantillation “offers a classic locus” for discourses that embody “musical corpora of the Jews with what can be called the ‘aura of antiquity’” (47).

[3] See sections I.3 and V.1 in Powers et al., 2015. Idelsohn is referenced in both sections as one of the main sources for the modern musicological use of the term. Dalia Cohen (2006, 203–15) critiques Western concepts of mode that focus only on melody type, noting that modal frameworks in traditions around the world are defined differently, and they index both musical and extra-musical elements. Musical features may include not only scale and melody type, but also tempo, meter, and instrumentation. Extra-musical features may include occasion (e.g., time of day, season), holiday, ethos, text, and function. All of these are relevant to the modes of Biblical cantillation in Jewish traditions.

[4] Comparisons between the modes of cantillation and prayer modes (steiger) can be made, and I will mention a few along the way. The focus here, however, is on a fully contextual analysis of cantillation melodies themselves. Idelsohn ([1929] 1944, 72–89) proposed that the prayer modes derive from cantillation, and this contributed to his larger argument that all Jewish music shares common characteristics, which come from the ancient Near East. As Tarsi (2001, 3) observes, however, Idelsohn does not explain specifically how the prayer and cantillation modes are linked. Specific motivic links can be found in Cohon (1950) and Kalib (2002); Kalib also compares Western and Eastern Ashkenazi traditions. For a valuable analysis of the prayer modes on their own, see Tarsi 2001, 2001–2, and 2002. Judah Cohen (2009, 74–77 and 156–76) provides an overview of the scholarship on Jewish prayer modes and describes their use in cantorial training at Hebrew Union College’s School of Sacred Music.

[5] See Frigyesi’s (2000, 4–5) discussion of the potential fusion of a physical book and the ideas, feelings, and images that it elicits—the experience of such a fusion is likewise strategic and context dependent.

[6] Frigyesi’s work focuses on Eastern-European communities from before World War II. Rich ethnographic work on current practices in the United States can be found in Summit 2000 and forthcoming, Slobin 2002, and Cohen 2009. Summit’s forthcoming book in particular focuses on cantillation.

[7] I thank Cantor Sacks for providing these recordings. Individual styles of cantillation, both lay and professional, will be addressed in a separate paper.

[8] Dresher (2013) correlates the Tiberian system of te’amim with the modern prosodic hierarchy, theorized in Selkirk 1984 and 1986, Nespor and Vogel 1986, and Hayes 1989. The correspondence is not perfect, but it is clear that where syntax and prosody diverge, the phrasing of the te’amim follows prosodic groupings. Janis 1987 and Strauss 2009 provide additional explanations for the linguistic function and logic of the te’amim.

[9] The translation is adapted from the second edition of the JPS Hebrew-English Tanakh (1999). The transliteration throughout this article is based on a combination of Association for Jewish Studies (AJS) and Union of Reform Judaism (URJ) guidelines. The apostrophe is used for sh’va nah; hyphens separate consecutive vowels that belong in separate syllables; and hyphens are occasionally used in additional places to clarify syllabification. There are a few exceptions that follow common usage, e.g., “te’amim” and “ta’am.” The transliteration follows modern (Sephardi) Hebrew.

[10] Jacobson 2013 and Strauss Sherebrin 2013 also use lines in this way to show the parsing at multiple levels.

[11] I adapt this labeling system from Dresher 1994, 2008, and 2013. Dresher uses “D0” for the highest level, then D1, D2, and D3.

[12] Jacobson’s chart is based on Price 1996.

[13] An alternative method teaches the te’amim all at once with their melodies, in the order of the “zarka table,” so named because it begins with the ta’am zarka. The zarka table was also used in early transcriptions of the te’amim; see Avenary 1978.

[14] The only exception is with the level-one disjunctives; sof pasuk is stronger than etnaḥta.

[15] The term “recursive dichotomy” is from Jacobson (2002, 57), and it is adapted from “continuous dichotomy” in Wickes (1881) 1970.

[16] I take this leveled bracket notation from Jacobson 2002; Jacobson adapts it from notation by Michael Perlman (see Jacobson 2002, 36). Dresher’s tree diagrams show the same process of division and analogous marking of levels; see, for instance, Dresher 2013, 294. See also the verse analyzer in the “TanakhML” project online: http://www.tanakhml.org/index.htm (accessed September 20, 2014).

[17] Jacobson (2002, 73–74) and Goren (1995, 43–44) likewise indicate that zakef katon (and zakef gadol) mark a stronger break than tipcha when they occur in succession. Goren (1995, 43–44) and Kogut (1994, 20–23) show more generally that there is not a direct correlation between the level of the disjunctive and its strength. This can be seen in Example 2c, which represents half of the verse. The level-three pashta is more-or-less equivalent in strength to the level-two tipcha since they each divide a quarter of the verse into eighths.

[18] The recording is from online resources associated with the “History of the American Cantorate” project (Slobin 1984–86). Spiro is “Cantor 01” in the sung examples, http://wesscholar.wesleyan.edu/sung/. Spiro (1922–2008) was a leading cantor of his generation; an interview with him, which is also part of the “History of the American Cantorate” project, can be found here: http://wesscholar.wesleyan.edu/interviews/32/. Spiro (1964) also provides pedagogical materials with notation for Haftarah chanting. More recent pedagogical texts and materials are cited below.

[19] Cohen (2003–8) uses barlines of varying width with numbers to indicate phrase boundaries associated with the multiple levels of disjunctive te’amim.

[20] Jacobson (2002) and Cohen (2003–8) similarly differentiate introductory notes from those that set the accented syllables. Jacobson uses stemmed and unstemmed pitches, as I do here, but he stems all of the pitches from the beginning of the accented syllable to the end of the ta’am (see page 517). Jacobson and Cohen also include a further level of rhythmic differentiation; Jacobson uses eighths, quarters, and half notes to indicate approximate durations (see page 518), and Cohen uses plain open circles and open circles with a “hold” designation. I do not include this level of rhythmic differentiation because it is a variable feature of oral practice and it is not necessary for the present analysis. Several pedagogical sources notate rhythm precisely; see, for example Binder 1959, Portnoy and Wolff 2000 and 2001, and Trope Trainer Software (produced by Kinnor Software, www.kinor.com).

[21] There are five exceptions: pashta, zarka, segol, and t’lisha k’tanah are placed over the final letter of the word, and t’lisha g’dolah is placed over the first letter. Some editions produce these te’amim twice, as needed: once in its expected place at the end or beginning of the word and once over the accented syllable (Jacobson 2002, 418).

[22] Jacobson (2002, 731), Kalib (2002; vol. 1, part 1, 40), and Ne’eman (1954–71; vol. 1, 139) also indicate that Haftarah cantillation is built on a minor scale with emphasis on scale-degrees 1, 3, and 4. The prayer mode magen avot is based on a minor scale and it has been said to be closely related to Haftarah cantillation (Idelsohn [1929] 1944, 84), but magen avot has recitation and pausal tones on 5 and 7 (Tarsi 2002, 61–63), not 3 or 4.

[23] Small differences between Example 3 and 4 have to do with the accentual properties of the words and text underlay. For instance, the first word in Isaiah 40:27 is a two-syllable word with the accent on the first syllable: “la-mah.” The accented syllable gets the pitch G (4), the unaccented syllable descends to D (1) (Example 3). In comparison, the ta’am that goes with “lamah” is “ma-pakh,” with an accent on the second syllable. The accented syllable of “ma-pakh” lands on G with a skip down to D (4 to 1).

[24] Scale degree 6 is prominent in the phrase kadma v’azla (as a local highpoint on an accented syllable), in the melismatic figure for munaḥ katon (as a local highpoint), and in the figure at the end of readings, transitioning to a new pitch center for the blessings after the Haftarah (Portnoy and Wolff 2001, 83–84; Kalib 2002; vol. 1, part 2, 45–46). Scale degree 2, on the other hand, occurs only as a passing tone between 1 and 3.

[25] The same kind of variability can be found in the database of recordings on the American Cantorate website (Slobin 1984–86). I tabulated all ninety-four versions of etnaḥta in the recordings of Isaiah 40:28. Eighty-eight of these (93.6%) have the <1, 3, 5, 4> melody in some form. Seventeen (18%) begin the melisma on 1 as in Spiro’s version; thirty-five (37%) use the more syllabic version documented by Kalib; and thirty-six (38%) sing a version that is more even melismatic than Spiro’s: <3-1-3-5-4>.

[26] Avenary (1978, 78–83) provides information on the background of the authors whose notation he uses, to establish their reliability as informants.

[27] Ne’eman 2012 provides a rigorous, computational study of variability in the practice among readers in the Eastern Ashkenazi and Moroccan traditions in Israel, with the Jerusalem-Sephardi tradition as a control group. Ne’eman finds that the Ashkenazi tradition is the least variable, the Moroccan tradition is more variable, and the Jerusalem-Sephardi tradition is the most variable. Where there is variability, readers typically maintain a consistent contour and final pitch (Ne’eman 2012, 59). Ne’eman’s study focuses entirely on Torah reading apart from the High Holidays.

[28] Kalib 2002 on its own includes many of the common variants; it will thus serve as a frequent source for the Examples provided here.

[29] Jacobson writes, “The multiplicity of oral musical traditions for the te’amim is a blessing, one to be cultivated rather than eliminated. That multiplicity goes hand-in-hand with the oral/aural process. … There are many musical traditions for chanting the te’amim. Minute melodic changes are accepted in most communities, as are legitimate traditional cultural variations” (2002, 515).

[30] Jacobson welcomes improvisation along these lines: “The pitches notated in this book need not be imitated slavishly. Rather, the motifs should be internalized by constant repetition until the student feels comfortable with his/her ownership of them. The student should be able to manipulate them freely and smoothly in the traditional combinations” (2002, 515). The idea that some variance is to be expected is also apparent in Pinchas Spiro’s methodology, documented in his interview for the American Cantorate Project (Slobin 1983-86). Before publishing his book on haftarah chanting, Spiro sent a questionnaire to other knowledgeable cantors. He provided melodies and for each, asked the respondents to indicate one of three choices: “This is exactly the way I do it, or, this is not exactly but close enough that I would accept it, or it’s completely different, in which case I asked them to supply me with their version.” The interview can be found at http://wesscholar.wesleyan.edu/interviews/32/; the passage about his questionnaire is at 31:27–32:08.

[31] Frigyesi (2002) discusses the flexibility of Eastern Ashkenazi liturgical music; she observes that this flexibility “is not an accidental by-product of oral transmission,” rather “it was brought about by a common desire, among East-Ashkenazi Jews, to allow for multiple expressive potentialities in the prayer” (2002, 116–17). Cantillation is more fixed and standardized than nusaḥ (the manner, mode, and melodies of prayer), as Frigyesi also observes (2002, 120), but at least in some contexts, the ethos that allows for variability in nusaḥ carries over into cantillation.

[32] This particular verse from Isaiah would not be chanted with High Holiday trope. I am using this set of te’amim, which includes the most common phrases, as a general template for comparison of the modes.

[33] I have transposed Kalib’s notation for the High Holiday melodies down a fourth for ease of comparison.

[34] If the final syllable of the word is unaccented, then the accented syllable is on 3 and the final syllable is on 1; the figure becomes <3-2, 1> instead of <3-2-1>. The ta’am t’vir (a level-three disjunctive) also ends with <3-2-1> in High Holiday trope; this figure is thus one of the fingerprints of the mode.

[35] A few motives in the High Holiday mode extend up to Bb; the complete scale is then Mixolydian. The prayer mode adonai malach also uses a Mixolydian scale, but adonai malach does not focus on the second scale degree; see Tarsi 2001 3, 11, and 16.

[36] Kalib interprets the final note as the tonic, but he also observes that subsidiary cadences “simulate a minor tonality structured on [the] second scale-degree” (2002; vol. 1, part 1, 39). Jacobson (2002, 924) shows the lower C as the tonic with D, E, and G as additional cadence pitches. (The pitch level is the same as in the transcriptions here; D is the tonic of a minor scale and C is the tonic of a major scale one whole step down.) Ne’eman’s High Holiday trope uses a different scale, a Dorian scale with an augmented fourth. Transposed to the pitch level of the examples here it would be

[37] There are differences in other variants of Lamentations trope from the Eastern Ashkenazi tradition, but they all emphasize a major key in the phrase ending with katon (D2) and the relative minor in the phrases ending with etnaḥta (D1) and sof pasuk (D1f). In some versions, the mapakh motive is more triadic, emphasizing 1, 3, and 5 in the relative major, and katon sometimes descends 3-1 instead of 5-1. All variants feature the stepwise descent in two part with <6-5-4> and then <3-2-1> for the phrases ending in etnaḥta and sof pasuk. The summary of cadence pitches for Lamentations trope in Jacobson 2002 (882) shows a strong emphasis on F and C (1 and 5 of the relative major) with etnaḥta and sof pasuk ending on D (1 of the relative minor). Ne’eman 1954–71 (vol. 2, 246–49) also shows the interaction of relative major and minor keys in Lamentations trope.

[38] The prayer mode magen avot is also in minor with shifts to the relative major; see Tarsi 2001–2. The arrival on 3 with phrases ending in katon and the parallel figures <6-5-4> and <3-2-1> are distinctive features of Lamentations trope.

[39] The overall effect of collapse, with major giving way to a stepwise descent in the relative minor, matches the message of the text in this verse: once the city [of Jerusalem] was great and abundant, now it is lonely and abandoned. The correlation is unique to this verse, but it is of interest nonetheless; it is a unique moment that occurs at the very beginning of the reading. I address correlations of this kind and the fact that they occur largely by chance in a separate paper (Malin 2015).

[40] Kalib’s (2002; vol. 1, part 2, 47) notation also includes a variant that descends to C, outlining the full C major triad.

[41] These figures may be heard to form a motivic link with Lamentations trope, although the placement of the accented syllable and length of the melisma is different. In Lamentations trope, the figure is <3-2-1> with the accented syllable on 3; in Esther trope it is <3, 2-1> with the accented syllable on 2.

[42] Boaz Tarsi mentions Esther cantillation as an instance of Ashkenazi liturgical music in which the ending note or final (finalis) is not the same as the tonic (2002, 157). Tarsi observes that Esther cantillation includes patterns in minor and the relative major, but the final cadence is on the fourth scale degree.

[43] There is a common variant of Esther trope in which both the etnaḥta and the sof-pasuk phrases end on G or a transpositional equivalent, a fourth above the tonic of the relative minor key (see Jacobson 2002, 842–43; Kalib 2002; vol. 1, part 2, 47–48; and Cohen 2003–8). This strengthens the sense of G as a tonal center and differentiates the Esther mode more strongly from Lamentations mode—but the tonality as a whole remains mobile. The G arrivals are not otherwise prepared.

[44] Comparison with features of common-practice tonality are inevitable—and not entirely inappropriate since Ashkenazi cantillation has co-existed with tonality in European culture since 1600. Ne’eman observes that melodic variants of a given ta’am in the Ashkenazi tradition often adhere to the same harmony; he thus argues for an implicit tonal awareness and orientation (Ne’eman 2012; 8, 88, and 99). Kalib (2002, vol. 1, part 1, 38) describes Torah trope as a “tonally-focused major mode,” and he notes the effect of half cadences with the phrase endings in 2.

[45] The variant in Example 10b can also be found in Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 43), Neeman 1954–71 (78), and Binder 1959 (117–18).

[46] The variants of katon in Examples 10a and 10b are permutations of each other; 10a has <5, 3-2> and 10b has <3, 5-2>. Permutation is an interesting and perhaps unexpected kind of variation, within the tradition—although it is also notable that the final pitch remains the same. A roughly analogous permutation can be found in variants of the Haftarah sof pasuk documented in Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 45); these include <3, 7, 1> and <7, 7, 3-1>.

[47] The ending with F going down to C does not seem to be common in Israeli Ashkenazi communities; see Ne’eman 2012, 73. The melodies in Example 10b may also be heard with C as tonic (in this notation). The scale would then be Mixolydian, as in the prayer mode adonai malach. The adonai malach mode, however, emphasizes the third from G to Bb (scale degrees 5 to 7; see Tarsi 2001); most of the motives in the Torah mode avoid or pass quickly through Bb. Tarsi (2002) explores the general phenomenon of liturgical music with phrases and sections that do not end on the tonic.

[48] The scale-degree annotation in Example 11 is entirely in C major since E minor is not very clearly established. One could, nonetheless, also hear the opening phrase as <4, 3-1, 1-3, 5-4 …> in E minor.

[49] Tipḥa is the most common disjunctive accent; it occurs 24.16% of the time among the disjunctives (Jacobson 2002, 412).

[50] Example 12 presents common versions of merkha-tipḥa in each mode, as notated in multiple sources. The merkha-tipḥa melody sometimes varies depending on whether it is leading up to etnaḥta or sof pasuk; in these cases, I have chosen the version that leads up to etnaḥta. The High Holiday tipḥa shown in Example 12 can be found in Portnoy and Wolff 2000 and Jacobson 2002; this differs from the Kalib’s High Holiday tipḥa shown in Example 6.

[51] I use the term “recitation tone” to refer to a repeated pitch which also functions as both the beginning and ending of a phrase. Tarsi identifies a recitation tone in Jewish liturgical music when a pitch is used “for at least one word plus a syllable from the previous or the following word” (2001–2, 61).

[52] The High Holiday merkha-tipḥa in Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 1, 2, 44) moves up to 2 and does not return to 1. Even in this version, the High Holiday phrase does not ascend as strongly or decisively as the haftarah phrase.

[53] Among the disjunctives, r’vi-i occurs 5.98% of the time (Jacobson 2002, 412). For more on how and when r’vi-i combines with the other phrases, see Jacobson 2002, 139–43 and 159–61.

[54] These include individual parts or aliyot in a Torah reading, the end of a Haftarah reading, and individual chapters in Lamentations, Esther, and the festive megillot.

[55] Example 13 uses the Torah melodies from Kalib 2002 (vol. 1, part 2, 43) as in Example 10a.

[56] The melodies for r’vi-i in Example 15 can all be found in multiple sources.

[57] Upper-case letters and Roman Numerals represent resting tones with associated major scales; lower-case letters and Roman Numerals represent resting tones with associated minor scales.

[58] The end-of-section melodies in Example 16 can be found in multiple sources, sometimes with small variations. I have not included scale degrees as in Example 15; the tonal implications should be apparent.

[59] Similarly, Kofi Agawu writes, “Analysis sharpens the listener’s ear, enhances perception and, in the best of cases, deepens appreciation” (2004, 270). Nicola Dibben emphasizes the rhetorical and creative aspects: “Music analysis and criticism are concerned with persuasion rather than proof, with providing ways of experiencing music … one function of theoretical accounts is to provide new ways of hearing (or imagining) music—in effect, to produce music” (2012, 350).

[60] Agawu writes, “Analysis is ideally permanently open … it is dynamic and ongoing … it is subject only to provisional closure' (2004, 270).

References

Agawu, Kofi. 2004. “How We Got out of Analysis, and How to Get Back in Again.” Music Analysis 23, no. 2-3: 267–86.

Avenary, Hanoch. 1978. The Ashkenazi Tradition of Biblical Chant between 1500 and 1900: Documentation and Musical Analysis. Tel-Aviv: Tel-Aviv University and the Council for Culture and Art.

Baer, Abraham. (1883) 1953. Baal t'fillah; oder Der practische Vorbeter. New York: Sacred Music Press.

Bakulina, Ellen. 2014. “The Concept of Mutability in Russian Theory.” Music Theory Online 20, no. 3.

Binder, Abraham W. 1959. Biblical Chant. New York: Sacred Music Press.

Cohen, Dalia. 2006. Mizraḥ u-ma’arav b’musikah [East and West in Music]. Jerusalem: Hebrew University Magnes Press.

Cohen, Miles B. 1972. “Masoretic Accents as Biblical Commentary.” Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society of Columbia University 4, no. 1: 2–11.

———. 2003–8. Nusaḥ Guides for Cantillation of the Te'amim.

Cohen, Judah M. 2008. “Whither Jewish Music? Jewish Studies, Music Scholarshp, and the Tilt between Seminary and University.” AJS Review 32, no. 1: 29–48.

———. 2009. The Making of a Reform Jewish Cantor: Musical Authority, Cultural Investment. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Cohon, Baruch Joseph. 1950. “The Structure of the Synagogue Prayer-Chant.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 3, no. 1: 17–32.

Dibben, Nicola. 2012. “Musical Materials, Perception, and Listening.” In The Cultural Study of Music: A Critical Introduction, edited by Martin Clayton, Trevor Herbert and Richard Middleton. 343–52. New York: Routledge.

Dresher, B. Elan. 1994. “The Prosodic Basis of the Tiberian Hebrew System of Accents.” Language 70, no. 1: 1–52.

———. 2008. “Between Music and Speech: The Relationship between Gregorian and Hebrew Chant.” Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics 27: 43–58.

———. 2013. “Biblical Accents: Prosody.” In Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics. 288–96. Leiden: Brill.

Frigyesi, Judit. 2000. 'The Practice of Music as an Expression of Religious Philosophy among the East-Ashkenazi Jews.' Shofar 18, no. 4: 3-24.

———. 2002. “Orality as Religious Ideal: The Music of East-European Jewish Prayer.” Yuval 7: 113–53.

Goren, Zekharyah. 1995. Taʻame ha-miḳra ke-farshanut [The Te'amim as Interpretation]. Tel Aviv: ha-ḳibuts ha-meʼuḥad.

Hayes, Bruce. 1989. “The Prosodic Hierarchy in Meter.” In Phonetics and Phonology: Rhythm and Meter, edited by Paul Kiparsky and Gilbert Youmans, 201–60. San Diego: Academic Press.

Hitin-Mashiah, Rachel, and Uri Sharvit. 2013. “Biblical Accents: Musical Dimension.” In Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics, edited by Geoffrey Khan, 283–88. Leiden: Brill.

Idelsohn, Abraham Z. (1929) 1944. Jewish Music in its Historical Development. New York: Tudor Publishing.

Jacobson, Joshua R. 2002. Chanting the Hebrew Bible: The Complete Guide to the Art of Cantillation. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society.

———. 2013. “Biblical Accents: System of Combination.” In Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics. 301–4. Leiden: Brill.

Janis, Norman. 1987. A Grammar of the Biblical Accents. PhD diss., Harvard University.

Kalib, Sholom. 2002. The Musical Tradition of the Eastern European Synagogue. Vol. 1, Introduction: History and Definition. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Khan, Geoffrey. 2000. “Review of Simcha Kogut, Correlations between Biblical Accentuation and Traditional Jewish Exegesis: Linguistic and Contextual Studies.” Journal of Semitic Studies 45, no. 2: 384–85.

———. 2012. A Short Introduction to the Tiberian Masoretic Bible and Its Reading Tradition. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press.

Kogut, Simcha. 1994. Ha-mikra bein te’amim lefarshanut: beḥinah leshonit ve-inyanit shel zikot u-maḥlokot bein parshanut ha-te’amim la-parshanut ha-mesoratit [Correlations between Biblical Accentuation and Traditional Jewish Exegesis: Linguistic and Contextual Studies]. Jerusalem: Magnus Press.

Lewin, David. 1969. “Behind the Beyond: A Response to Edward T. Cone.” Perspectives of New Music 7: 59–69.

Malin, Yonatan. 2015. “Music-Text Relations in Ashkenazic Cantillation: A New Analysis.” Paper presented at the conference Magnified and Sanctified: The Music of Jewish Prayer. University of Leeds, UK, June 2015.

Ne’eman, Mordechai. 2012. Ha-yisod ha-musikali shel ha-kriah batorah l’fi ta’amei ha-mikra: nituaḥ structuali v’hashva’ati [The Musical Basis of Biblical Reading according to the Masoretic Accents: A Structural and Comparative Analysis]. PhD diss., Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Ne’eman, Yehoshua L. 1954–71. Tzeliley hammiqra: yesodot ha-musikah shel ha-te’amim [The Cantillation of the Bible: Musical Principles of the Biblical Accentuation]. 2 vols. Tel Aviv: Moreshet.

Nespor, Marina, and Irene Vogel. 1986. Prosodic Phonology. Dordrecht: Foris.

Portnoy, Marshall, and Josee Wolff. 2000. The Art of Torah Cantillation: A Step-by-Step Guide to Chanting Torah. New York: URJ Press.

———. 2001. The Art of Cantillation, Vol. 2: A Step-by-Step Guide to Chanting Haftarah and M'gillot. New York: URJ Press.

Powers, Harold S. et al. 2015. “Mode.” Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed August 22, 2015.

Price, James D. 1996. Concordance of the Hebrew Accents in the Hebrew Bible. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

Rosowsky, Solomon. 1957. The Cantillation of the Bible. New York: Reconstructionist Press.

Schönberg, Jakob. 1927. Die traditionellen Gesänge des israelitischen Gottesdienstes in Deutschland: Musikwissenschaftliche Untersuchung der in A. Baers “Baal T’fillah” gesammelten Synagogengesänge. PhD diss., Friedrich-Alexanders-Universität.

Selkirk, Elizabeth O. 1984. Phonology and Syntax: The Relation Between Sound and Structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

———. 1986. “On Derived Domains in Sentence Phonology.” Phonology Yearbook 3: 371–405.

Seroussi, Edwin. 2009. “Music: The ‘Jew’ of Jewish Studies.” Yearbook of the World Union of Jewish Studies 46: 3–84.

Slobin, Mark. 1984–86. American Cantorate. Online database associated with the “History of the American Cantorate Project.” http://wesscholar.wesleyan.edu/cantorate/.

———. 2002. Chosen Voices: The Story of the American Cantorate. 1st paperback edition. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Spiro, Pinchas. 1964. Haftarah Chanting. New York: Board of Jewish Education of Greater New York.

Strauss, Tobie. 2009. Hashpa’at gormim prosodim v’gormim aḥerim al ḥalukat te’ami k”a sfarim [The Effects of Prosodic and Other Actors on the Parsing of the Biblical Text by the Accents of the 21 Books]. PhD diss., Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Strauss Sherebrin, Tobie. 2013. “Biblical Accents: Relations to Exegetical Traditions.” In Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics, edited by Geoffrey Khan. 296–301. Leiden: Brill.

Summit, Jeffrey A. 2000. The Lord's Song in a Strange Land: Music and Identity in Contemporary Jewish Worship. New York: Oxford University Press.

———. Forthcoming. Singing God’s Words: The Performance of Biblical Chant in Contemporary Judaism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tarsi, Boaz. 2001. “The Adonai Malach Mode in Ashkenazi Prayer Music: The Problem Stated and a Proposed Musical Characteristics-Oriented Outlook.” World Congress of Jewish Studies 13.

———. 2001–2. “Toward a Clearer Definition of the Magen Avot Mode.” Musica Judaica 16: 53–79.

———. 2002. “Lower Extension of the Minor Scale in Ashkenazi Prayer Music.” Indiana Theory Review 23: 153–83.

Tenzer, Michael, ed. 2006. Analytical Studies in World Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tenzer, Michael, and John Roeder, eds. 2011. Analytical and Cross-Cultural Studies in World Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Weil, Daniel. 1995. The Masoretic Chant of the Bible. Jerusalem: Rubin Mass.

Wickes, William. (1881) 1970. Two Treatises on the Accentuation of the Old Testament. New York: Ktav Publishing House.