Atah Ehad, Shulamit and Oded Shremer, recorded by Naomi Cohn Zentner, 24 March 2012, Jerusalem.

Atah Ehad

The classification of traditional Ashkenazi melodies into clearly defined genres is a difficult, perhaps impossible task, since the same melody can function as a liturgical melody, a zemer for the Sabbath, a Hassidic niggun and a Yiddish folksong. In addition, some Ashkenazi tunes were reincarnated as Zionist songs, becoming Israeli folk songs and folk dances in both secular and religious contexts.

The song of the month, Atah Ehad (Thou Art One), is a well-known setting of a traditional Ashkenazi melody to a prayer from the Minhah service[1] (Heb. מנחה) for the Sabbath sung in Ashkenazi synagogues in Israel:

אַתָּה אֶחָד וְשִׁמְךָ אֶחָד וּמִי כְּעַמְּךָ יִשְׂרָאֵל גּוֹי אֶחָד בָּאָרֶץ.

תִּפְאֶרֶת גְּדֻלָּה וַעֲטֶרֶת יְשׁוּעָה יוֹם מְנוּחָה וּקְדֻשָּׁה לְעַמְּךָ נָתָתָּ.

אַבְרָהָם יָגֵל, יִצְחָק יְרַנֵּן, יַעֲקֹב וּבָנָיו יָנוּחוּ בוֹ,

מְנוּחַת אַהֲבָה וּנְדָבָה, מְנוּחַת אֱמֶת וֶאֱמוּנָה, מְנוּחַת שָׁלוֹם וְשַׁלְוָה וְהַשְׁקֵט וָבֶטַח,

מְנוּחָה שְׁלֵמָה שָׁאַתָּה רוֹצֶה בָּה,

יַכִּירוּ בָנֶיךָ וְיֵדְעוּ כִּי מֵאִתְּךָ הִיא מְנוּחָתָם וְעַל מְנוּחָתָם יַקְדִּישׁוּ אֶת שְׁמֶךָ.

The earliest documentation of the setting of this melody for Atah Ehad is in Idelsohn's second edition of Sefer Hashirim (Berlin 1922) which was intended to assemble a corpus of folksongs for the children of the Yishuv, the Zionist settlement in Palestine/Eretz Israel.[2] The melody is classified in Sefer Hashirim as a 'Ne’ima ‘amamit Hassidit' (Hassidic folk melody) testifying that it was already known to the editor from a Hassidic context.

Score no. 1: A. Zvi Idelsohn, Sefer Hashirim, Kovetz Hadash leganey Hayladim, ulvatei hasefer haamamiyim labayit velemakhela (The Book of Songs, a new collection for kindergartens, Elementary and High schools, for home and for choirs), Berlin, Juedischer Verlag 1922, 63-64.

In this arrangement, which Idelsohn wrote from right to left – since he believed the score should follow the natural direction of the Hebrew language – the melody is set as a responsorial piece for two voices with a soloist and the choir alternating. The modal framework is a natural minor, which is divergent from its original Hassidic usage, as we shall see below.

Although Idelsohn can be credited as the first musician to introduce this melody to the Zionist repertory and responsible for its appearance in later Zionist songbooks, one must bear in mind his preface to the second edition of Sefer Hashirim in which he indicated that many of the melodies in this publication were already popular at that time (1922) in the Yishuv.

'כמעט כל השירים המכונסים בקובץ החדש הזה מושרים בארץ ישראל, בבתי הספר ובפי העם. '[3]

(“Almost all the songs in this new edition are sung in the Land of Israel in schools and are in the mouth of the people”).

Following Idelsohn's publication of Atah Ehad, other contemporary Zionist songbooks reproduced it, sometimes in Idelsohn's choral arrangement, such as Hawa Naschira (Hamburg 1935).

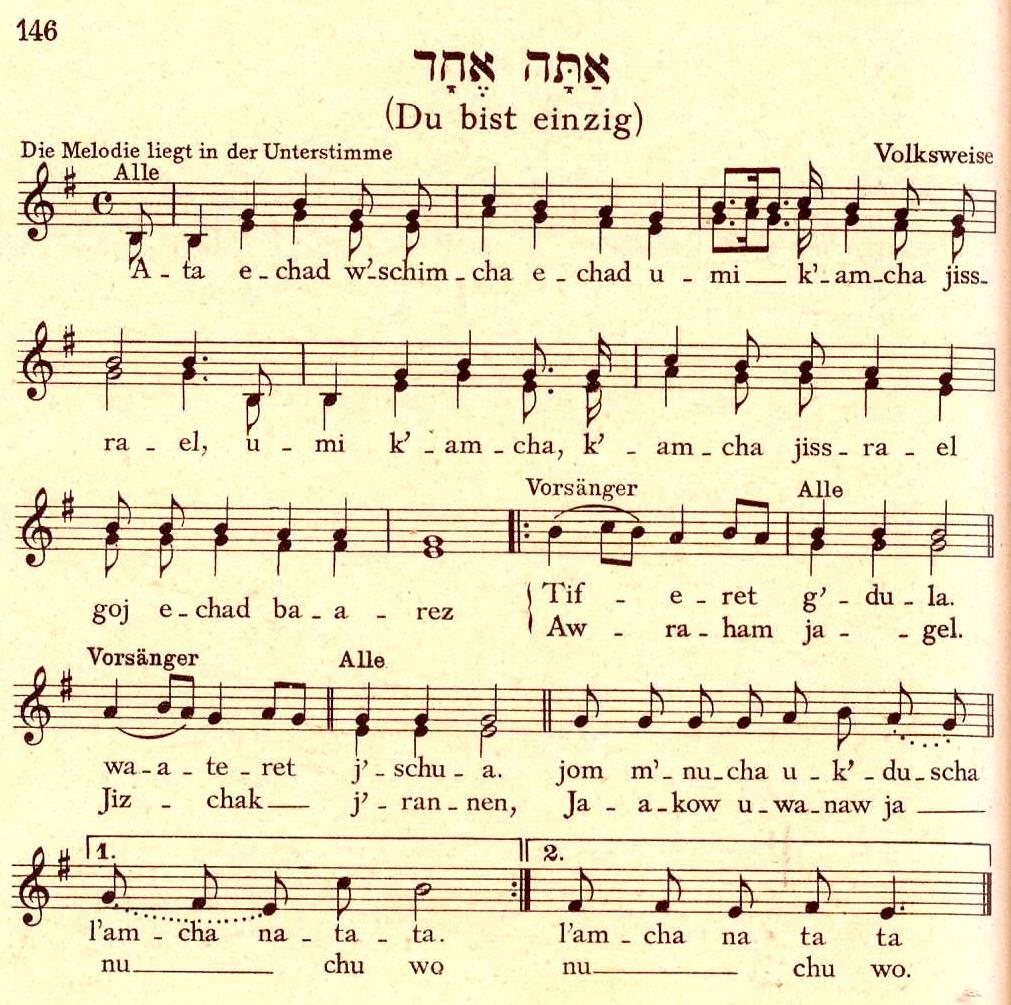

Score no. 2: Erwin Jospe and Joseph Jacobsen, Hawa Naschira - Auf! Lasst uns singen!, Leipzig, Hamburg: Anton J. Benjamin A.G., 1935, p. 146.

Recordings of the tune's contemporary and historical performance practice attest to its popularity in Israel as a liturgical tune, sung in the Minhah prayers for the Sabbath, and also as a song sung in youth movements and in 'shira betzibur' (communal sing-along events). However these recordings also reveal minor deviations from Idelsohn's arrangement. For example, although Idelsohn instructs the singers to return to the A part at the end of the melody, the song was not performed in this form even as early as 1935 (as can be seen in score no. 2). In addition, certain phrases intended for the second and not primary voice in Idelsohn's choral arrangement crystalized as the song's main melody line. This can be heard in recording no. 1 of the song as it was sung in the 1940s and 1950s, in the Jerusalem branch of the religious Zionist movement Bnei Akiva when in measure 10 (for the word gedulah) G is sung instead E.

The confusion in voice parts may be the reason that in the 1935 Hawa Naschira version a special instruction is added to Atah Ehad indicating that the melody is in the lower voice ('Die Melodie liegt in der Unterstimme'; see score no. 2).

Although the song continued to be sung in its liturgical context, Atah Ehad was not sung exclusively by religious youth movements. In her nostalgic autobiography in song, Netiva Ben Yehuda (see link below) mentions this melody as one of the “Hassidic tunes” sung in the 1930s at the Gimnasya Herzeliya, one of the central schools of the Zionist elites in Tel Aviv, and in the secular youth movements as part of the 'Shirei yom shishi' (“Friday/Sabbath Eve songs”).[4]

Score no. 3: Atah Ehad in Netiva Ben Yehuda, Otobiografia beshir vazemer (An autobiography in song and melody) Jerusalem: Keter, 1990, p. 137.

The popularity of Atah Ehad in Zionist youth movements is clear but it remains to be determined whether its publication in Idelsohn’s Sefer Hashirim and in other Zionist songbooks was the fact that introduced this melody into these Zionist institutions or whether it merely reflected its common usage in the early twentieth century.

The same melody set to the words 'Besefer hayyim berakha veshalom' from High Holidays’ liturgy was part of the repertory of Shlomo Zalman Rivlin's children choir “Shirat Yisrael” that was active in Jerusalem in the 1940s. It appears in the third volume of his collection of compositions Shirey Shlomo (Jerusalem 1962).

Score no. 4: 'Besefer hayyim' in Shirey Shlomo, ed. Shlomo Zalman Rivlin, Jerusalem: Shirat Yisrael publications, 1962, p. 89.

Idelsohn's qualification of the melody as “Hassidic” is of course accurate as attested by recent recordings in Hassidic Tishes with other texts. When sung in Hassidic contexts it appears either as a textless niggun or with the seventh strophe from the piyyut “El mistater beshafrir heviyon,” a Sephardic kabbalistic poem by R. Abraham Maimon (late sixteenth-century Syria) starting 'Yah zekhut avot yagen ‘aleinu' (see recording no. 2 and no. 3). Another setting of this melody appears with the text “Barukh el eliyon,” a zemer for Shabbat sung by Hungarian Jews (see recording no. 4 and no. 5).

These Hassidic recordings of the melody of Atah Ehad capture the typical Hassidic style of performance, such as slow tempo and the characteristic tempo fluctuations. Phrases often build up to a relatively strict, if slow tempo while the end of the phrase has a ritardando leading to an almost stand still at the final note of the phrase.

As far as modal makeup, the Hassidic version of the melody can be seen as belonging to the Magen Avot shteyger, which is based on a natural minor tending to a lowered second degree especially in the final cadences, creating a Phrygian sonority. In comparison to these Hasidic versions, Idelsohn's notation and arrangement is in a straight natural minor Such a deviation from the liturgical modes into minor and major is characteristic of Zionist renditions of traditional Ashkenazi tunes, Hassidic and non-Hassidic. Idelsohn was at the forefront in the adoption of these strategies of modal modification.

The comparison of various Hassidic renditions of the melody in the table below reveals that they are all related to the ABCB structure that is typical of Hassidic niggunim. Although the internal order of the motivic material in the B section varies in the different versions, this section ends the piece in all versions. Structural variations of the melody show even when Hassidim belonging to the same dynasty sing the melody to the same text, as is the performances of “Ya zekhut avot” by Rabbi David Levanon and by the Bohush Hassidim from Bnei Brak in the 'Yortseyt Tish' (1 and 2 in the table). These performers are all connected to the Bohush dynasty originating from Bukovina (Moldavia, today divided between Rumania and Ukraine).

|

No. |

Performer |

Detailed structure |

Reduced structure |

Text |

|

1 |

Levanon (recording 2)

|

AB(=b1 b2 b3 b4) C (ending in b3 as per Rotenberg's)C (b3) B

|

ABCCB= ABCB |

'Ya zechut avot” |

|

2 |

Bohush Hassidim (recording 3)

|

AB(=b1 b2 b3 b4) C (ending with b4), AB(=b1 b2 b3 b4) C (ending with b4) C (b3 b1 b2 b4) |

ABCABCCB'

|

'Ya zechut avot' sung at a Yortseyt Tish |

|

3 |

Deutsch (recording 4)

|

AB(=b1 b2 b3) B' (=b1 b2 b4)C (b3)BB' |

ABB'CBB'= ABCB |

'Barukh El Eliyon' |

|

4 |

Rotenberg (recording 5) |

AABB' (B=b1 b2 b3, B'= b1 b2 b4) C(b3) C (b3) BB'

|

AABB'CCBB'=ABCB

|

Textless. The singer mentions that it can be sung to the text 'Ish hassid haya' on Motzaei Shabbat |

Compared to the Hassidic rendition of the melody in the ABCB structure, Idelsohn's version uses only the first two sections resulting in a shortened ABB structure. This abbreviation of form was typical of Zionists adaptations of Hassidic. The ABB form of the melody of Atah Ehad is found in all settings of this song in Israel since Idelsohn's 1922 arrangement, apart from the performances in Hassidic circles.[5]

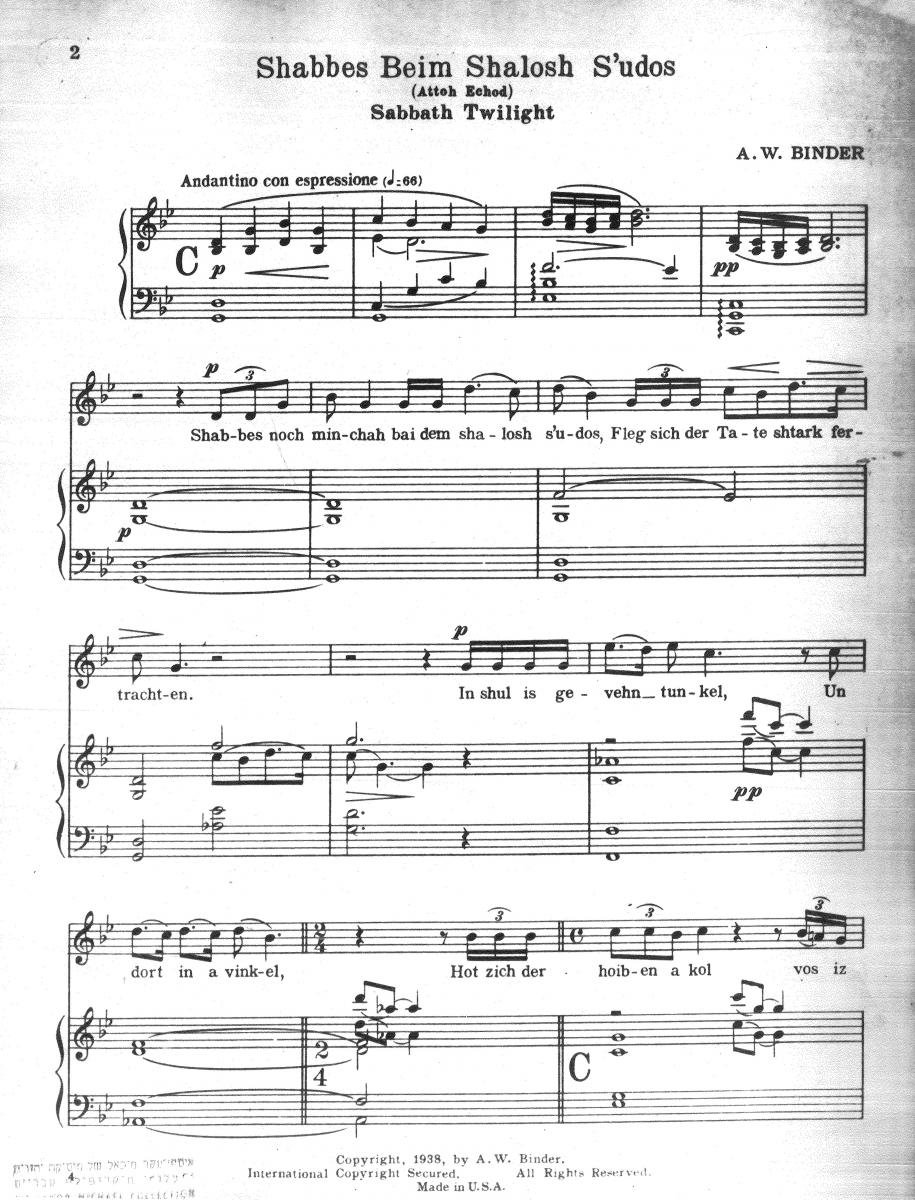

We will surmise to conclude that the melody of Atah Ehad predates Idelsohn’s notation and stems from Hassidic circles, especially from Southeastern areas of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and was adopted by Zionists in Palestine. The rather sad rendition of the tune in the Hassidic versions was suited to its performance in the Sabbath afternoon prayers when light is waning and the Sabbath is coming to its conclusion. The poet Haim Nachman Bialik identified Atah Ehad's air of longing and contemplation and incorporated its singing into his weekly 'Oneg Shabbat' events which took place on the Sabbath afternoon. We interpret this selection by Bialik as a gesture of memorialization symbolizing nostalgia for the Old World that was left behind by the Zionist dream. Abraham Wolf Binder emphasized this function of Atah Ehad as a substitute for the Minḥah service for the Sabbath in his recollection of Bialik’s Oneg Shabbat:

'The great poet Bialik, remembering the sacred impressions which the Sabbath had made upon him in his early youth, felt a void in the Sabbath as it developed in Palestine, and particularly in the city where he lived, Tel Aviv. He missed the gatherings of great multitudes of Jews on the Sabbath day in the Bet Ha-midrash to listen to the Holy Word and to sing together the Sabbath zemirot. The Oneg Shabbat which he initiated in 1929 was an institution to supply this need.[6] About fifteen hundred to two thousand Jews would gather in the Ohel Shem auditorium at about five in the afternoon. They then began with the singing, led by a group of men and boys banded together for the purpose of leading the gathering in Sabbath zemirot. They always included the prayer Attah Echad, 'Thou Art One,' an excerpt from the Sabbath afternoon liturgy, sung to a melody in Eastern European style. The tune represented the sanctity of the Sabbath and the longing which the Jew always had for the spiritual rewards of the day. This excerpt from the afternoon service was in lieu of the afternoon service proper. The tune was at first sung by a few, then was gradually caught up by more and more, until the tremendous voice of an entire people was carried away on the wings of song to upper levels, where 'dwells the Sabbath soul of the Jew.'[7]

The melody of 'Atah Ehad' was incorporated in a Yiddish art song titled 'Shabbes beim Shalosh S'udos' composed by Abraham Binder depicting the late Sabbath afternoon atmosphere and evoking a nostalgic view of the Eastern European diaspora.

Links

For information on Netiva Ben Yehuda see: http://www.zemereshet.co.il/artist.asp?id=646.

[1] See also: Aaron Rothkoff, 'Minḥah,' in Encyclopaedia Judaica ed. Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik vol. 4 2nd ed. (Detroit: Gale, 2007): 280-281.

[2] On Idelsohn's pedagogical goals in Sefer Hashirim see: Edwin Seroussi, ' A Common Basis — The Discovery of the Orient and the Uniformity of Jewish Musical Traditions in the Teaching of Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, Peamim: Studies in Oriental Jewry 100, (2004), pp. 125-146 (In Hebrew).

[3] Idelsohn, Sefer Hashirim, iii.

[4] Netiva Ben Yehuda, Otobiografia beshir vazemer [An autobiography in song and melody] Jerusalem: Keter, 1990, p. 137.

[5] More examples of Hassidic melodies shortened when used in Zionist context appear in Yaacov Mazor's article 'Miniggun hassidi lezemer ’ivri' [= From Hassidic niggun to Hebrew song, Katedra 115 (2005), pp. 95-128. Available online at: http://www.zemereshet.co.il/UserFiles/file/articles/cathedra/Mazor_Cathedra_115.pdf.

[6] Binder is quoting here from Ernst Simon, 'Der Entfuehrung des Oneg Shabbat in Tel Aviv', in Juedisches Fest Buch, Berlin, 1935.

[7] Abraham Wolf Binder, 'The Music of the Synagogue: An Historical Survey' in Studies in Jewish Music: Collected Writings of Abraham Wolf Binder, edited by Irene Heskes, New York: Bloch Publishing Company, 1971, pp. 101-102. (Originally written in 1944).