Musica Hebraica

The Music on Comtat-Venaissin

Revised and annotated translation from the French by Edwin Seroussi

Note: This article appeared in parallel columns in English, French and German in Musica Hebraica (1-2 [1938]: 18-20), the very short-lived journal initiated by the World Center for Jewish Music in Palestine. Milhaud, who was a close correspondent of this organization, obviously wrote his piece in French.[1] The translator to English took some noticeable liberties, at times concealing nuances in Milhaud’s casual French prose. The present version remains closer to the French original as much as possible in comparison with the Musica Hebraica English version. Clarifications to Milhaud’s text appear in square brackets and as footnotes, while hyperlinks assist the reader in search for additional information about names, places and concepts mentioned by the author.

When Marseilles, the Marsilia of Antiquity, was founded by the Greeks, Provence was already a center of commercial activity, flourishing on the trade of the Mediterranean before the beginning of the Christian era. They were then the only adherents of a monotheistic religion and there were cases of Gauls becoming Jewish converts.

These Jews remained in Provence and together with later comers, arriving via Rome after the destruction of the Second Temple, they formed the bulk of the Jewish population of Comtat-Venaissin. During the whole of the Middle Ages and up to the Revolution of 1789 they lived peacefully and contentedly under the administration of the Papal legate in the little enclave that the Sovereign Pontiff possessed between Avignon, Cavaillon, I'lsle-sur-Sorgues and Carpentras.

The music [in Comtat-Venaissin] was particularly brilliant; in a period before the French opera was born, art musicians from Italy produced at the Papal residence in Avignon solemn spectacles of dazzling splendor. In the carrières (or Comtadin ghettos) the Sephardic liturgy was not devoid of traces of the atmosphere of Provence.[2] Some of these sacred chants carried with them the reflection of these old farandoles whose rhythm unfolds with the same smoothness as the soft curves of the hills that border the horizon [of Provence].[3]

But, above all, it is the folklore that bears the profound double trace of the Jewish and the Provencal. The poems, chansons, piyyutim, the modest theatre plays for Purim, are all written in the Comtadin-Jewish dialect, a mixture of Hebrew and Provençal, which on occasion one still hears spoken here and there among the Jewish families of Provence; and a little dictionary of this language was published about half a century ago in a Jewish almanac. His Majesty Pedro II of Alcantara, Emperor of Brazil, who was interested in the study of languages, published an anthology of poems in which Hebrew verses alternate with Provençal ones.[4]

The poets of the Pontifical Court wrote poems designed to convert the Jews to Christianity; Jewish poets interpolated replies in Hebrew, refuting their arguments. In Aix I found among some Jewish family papers the manuscript of a little story, "Arcanoth and Barcanoth", that Armand Lunel, the great Comtadin writer, mentioned its existence in his accounts. It tells the story of a visit by two Jews to the Bishop of Carpentras, and the spirit of gaiety and good humor in which it is written testifies to the good relations which never ceased to exist between the Pontifical administration and the Jews of the Comtat.[5]

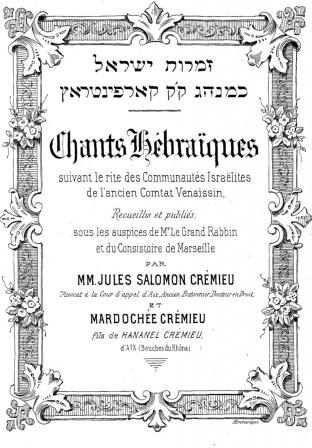

As regards musical records, the only document in our possession is a volume [Chants hébraïques: suivant le rite des Communautés Israëlites de l'ancien Comstat Venaissin] containing the principal songs, which was published at Aix in 1885 by Jules-Salomon Cremieux and [Mardochée son of] Hananel Cremieux. Aix was the last citadel of the Comtadin liturgy. Service is no longer held in the synagogues of Carpentras and Cavaillon, those adorable temples with their Louis XV and Louis XVI woodcarvings, which have been classed among historical monuments. The Aix synagogue dates back to 1840. Its community is at present presided over by my father [Gad Gabriel Milhaud, 1853-1942]. The synagogue was inaugurated by my great grandfather, Yossef Milhaud [1781-1870], who was the author of several religious books, including a "Commentary on Deuteronomy" and a "Life of Jethro", and it was opened to public religious services by its owner, my great-uncle [Moïse Jassé] Laroque [1816-1893], whose family still owns it. The chants there were in the purest Comtadin rite. Some fifty years ago, a cantor from Alsace was appointed to the temple of Aix, but he had to learn, as soon as possible, the Comtadin airs.[6] Today the Provençal pronunciation has almost disappeared, for only the sons [of the locals] and a few old people still maintain it. The officiating cantor who comes over from Marseilles for the festivals is a Sephardic Jew but not a Comtadin.[7]

I have watched the gradual disappearance of the Comtadin element among the Jewish community of Aix, owing to the passing of the older generation and, alas, the religious indifference of most of the youth. In proportion to its decline, a new element, which began to arrive around 1900, is steadily on the increase: the Algerian Jews who are fairly numerous at Aix and actually form a majority among the synagogue-goers.[8] A few years ago, they attempted to impose their forms of worship, but the remaining Comtadins offered a successful resistance. Yet the days of the Comtadin songs are gone, and the collection edited by Cremieux is the sole memorial of this sublime sacred music.

I have been greatly influenced by the character of this liturgy and I have harmonized some airs for Rosh Hashanah,[9] and Armand Lunel, whose work is to a large extent inspired by the Comtat, has furnished me with his "Esther de Carpentras," a libretto that connects to the purest Comtadin traditions. In fact, I have been extremely fortunate. There is a man like Armand Lunel, the author of "Niccolo Peccavi" or "The Dreyfus Affair in Carpentras", "The Rope-Maker's Vision", "Black and Grey"," and the "The Witch’s Broom"; he is the person who knows the best all that relates to the Comtat; the archives of the library of Carpentras and the Calvet Museum of Avignon are no secret to him.[10] Well, I got the chance to encounter him on the benches of the Lyceum in Aix. He arrived to Paris in 1909, in the same time as I did; he, to enter the École Normale and I to the Conservatoire. So, I always followed his first essays and our collaboration dates back to our lessons in philosophy at the Lyceum. I suppose it was destined that we should meet. As early as the thirteenth century, our surnames appear together in the register of the Jews of Carpentras, under the insignia of the Church; and in a later age they are to be found on a milestone between Nimes and Montpellier which bears the legend: Lunel, 11 km; Milhaud, 3 km. Again, one finds them on the scores of [Milhaud’s operas] "The Misfortune of Orpheus", "Esther of Carpentras" and "Maximilien" (whose French adaption was the work of Lunel).

[1] The WCJM and its journal Music Hebraica are extensively discussed by Philip Bohlman in The World Centre for Jewish Music in Palestine, 1936-1940: Jewish musical life on the eve of World War II (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992). On Milhaud’s correspondence with the WCJM see pp. 45-47. Milhaud was elected honorary President of the WCJM together with Ernest Bloch, see p. 125.

[2] This conceptualization of the Provencal Jewish liturgy as “Sephardic” is symptomatic of the realignment of French Jewry after the Revolution that forced the Provencal Jews, turned overnight into French citizens, to align themselves within the rigid Sephardic/Ashkenazi binary. The only document we possess for the Comtadin liturgical music tradition, the Chants hébraïques: suivant le rite des Communautés Israëlites de l'ancien Comtat Venaissin (discussed below by Milhaud) shows some musical connections with the Western Sephardic (aka Spanish-Portuguese) liturgy such as those of south-western France (Bayonne, Bordeaux). However, this volume also shows traces of autochthonous chants and even some Ashkenazi melodies.

[3] The farandole is an open-chain dance popular in Provence, similar to the gavotte, jig, and tarantella.

[4] Milhaud wrote by mistake “Pedro I”. See, Pedro II de Alcantara, Poésies hébraïco-provençales du rituel israélite comtadin (Avignon: Seguin, 1891). This publication is so suspiciously close to Ernest Sabatier, Chansons Hébraïco-Provençales Des Juifs Comtadins, Réunies et Transcrites Par E. Sabatier (Nîmes: A. Catélan, 1874) that a clarifying disclaimer had to be added in a footnote to the Emperor’s publication (on p. xiii): “Au dernier moment nous apprenons de M. Kahn, grand rabbin à Nimes, séjournant pour quelques semaines à Vichy, qu'un hébraïsant, à Nimes, M. Sabatier, a déjà tenté — sous ce titre : Chansons hébraïco-provençales des juifs Comtadins, réunies et transcrites par E. Sabatier. Nimes A. Catélan, libraire 1874, (épuisé et rare, sans l'hébreu en regard) — l’œuvre que nous donnons au public et qui est le produit personnel de S. M. Dom Pedro Il, car nous affirmons que jamais S. M. ni nous-même, n'avons eu Connaissance du travail de M. Sabatier (note du Dr C. F. Seybold du 3 août 1891).”

[5] Peter Nahon, Modern Judeo-Provençal as Known from Its Sole Textual Testimony: Harcanot et Barcanot (Critical Edition and Linguistic Analysis), Journal of Jewish Languages 9 (2021): 165–237.

[6] The cantor from Alsace was obviously of Ashkenazi (German) origin.

[7] Unlike our observation in note 2 above, here Milhaud distinguished between the Sephardic and the Comtadin liturgies. The visiting cantor from Marseille was most probably of North-African origins.

[8] Some information on Algerian Jews in Aix can be found in Elizabeth D. Friedman, Colonialism & After: An Algerian Jewish Community (South Hadley, Mass.: Bergin & Garvey Publishers, 1988).

[9] Darius Milhaud, Liturgie Comtadine: 5 Chants de Rosch Haschanah. Textes Français et Hébreu Avec Accompagnement de Piano. (Paris: Heugel, 1934)

[10] Most of the information provided by Milhaud reappears in Lunel’s much later publication: Armand Lunel, Juifs du Languedoc, de la Provence et des États français du Pape (Paris: Albin Michel, 1976). This extremely important work has been translated to English by Samuel N. Rosenberg with an introduction by Lunel’s grandson David A. Jessula in Hebrew Union College Annual 89 (2018), pp. 1-157. This similarity between Lunel and Milhaud’s text reflects the intense friendship and mutual admiration that both artists maintained throughout their lives. See Lunel’s posthumous publication, Mon Ami Darius Milhaud: Inédits, ed Georges Jessula (La Calade, Aix-en-Provence: Edisud, 1992).

See also the Song of the Month "A cantor’s pledge in the High Holyday’s Provençal liturgy (Minhag Carpentras)".