Meir Sullam (Ghardaia)

A cantor’s pledge in the High Holyday’s Provençal liturgy (Minhag Carpentras)

The Jewish liturgy was never a sealed and unified corpus. Its continuity and pertinence for different generations relied on the potential of the practitioners to embellish the basic and ancient core of the liturgy with particular additions and variations. Classic locations for such embellishments are petitions by the cantor or the shaliaḥ tzibbur (envoy of the congregation) inserted before the opening of the formal public prayer starting with the cry “Barekhu et Adonai hamevorakh” (Bless Adonai the Blessed One) or those inserted prior to the repetition of the ‘Amidah, the core set of prayers of every service.

The need to provide the prayer leader with a private moment to express the anxiety raised by standing on the pulpit to conduct the prayer on behalf of the community led since antiquity to the development of a self-contained liturgical poetic genre, the reshut. (Granat 2016) Although this term translates literally as “permission” or “consent” the Hebrew word also resonates with privilege, i.e. the honor conferred upon the cantor to fulfill such a mission.

However, the reshut was not always a creation of post-biblical poets. Liturgists also used selections of Psalm verses to attain the same effect. A set of such verses included in the liturgical order of the Jews of Provençe, the subject of this Song of the Month, fulfill a similar function to that of the reshut. This order of prayers, called Minhag Carpentras or Rit Comtadin was used by the Jews of the Papal States of southern France, an area also known as Comtat Venaissin or the Arba Qehillot (after the four “holy communities” of Avignon, Carpentras, Cavaillon, and l’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue). Minhag Carpentras can be considered as a “minor” liturgical order when compared to the predominantly canonical Sephardic and Ashkenazi ones in all their variants. Although aligned mostly with the Western Sephardic tradition, it contains unique texts such as the selection of Psalm verses whose music is discussed below.

The memory of the melodies and prayer intonations of the Rit Comtadin was already in sharp decline by the mid-nineteenth century. A perception of this decay, the result of the resocialization of the Comtadin Jews into the mainstream of post-revolutionary French Jewry (from 1799 onwards), led the remaining leaders of this unique community to preserve in music notation whatever was left from the liturgical repertoire in the memory of surviving connoisseurs. The result of this initiative was the compendium titled Chants hebraïques suivant le rite des communautes Israelites de l’ancien Comtat Venaissin (Paris: Delanchy: 1887), curated and edited by Jules Salomon Cremieu and Mardochee Cremieux.

Not enough attention was given to the content of this collection. Idelsohn (1929: 340-1) argued that it has “scientific value” adding that “these Jews were partly of those descended from the ancient community of Provence who remained in France after the expulsion of 1394 because they were protected by the Pope in Avignon and only a few of them were of the offspring of the refugees from Spain…They did not mingle with German Jews…Their traditional tunes differ to a great extent from those of all other Jewish communities. They contain elements of original Jewish modes intermingled with French chants of the Middle Ages. Peculiarly enough, these Jews accepted the German Ashkenazi Pessach tune of Adir Hu.” “Scientific” in Idelsohnian jargon meant that the transcribers attempted to faithfully convey the oral tradition in music notation without letting their personal biases or preferences intervene in the process. Considering the relative isolation of the Comtadin Jews, Idelsohn believed, following his historiographical logic, that they preserved older layers of Jewish musical memory although he did not discount also the possibility of local accretions (generically defined as “medieval French chants”). Musically speaking, Minhag Carpentras, as Chants hebraïques reveals, indeed shows a certain allegiance to the Western Sephardic traditions, especially those from Livorno. However, a closer look shows traces of North-African melodies, probably the result of migrations of Jews from Algeria and Morocco to Southern France since the early nineteenth century. As we shall see, the Psalm verses discussed below are an example of such cross-Mediterranean connections.

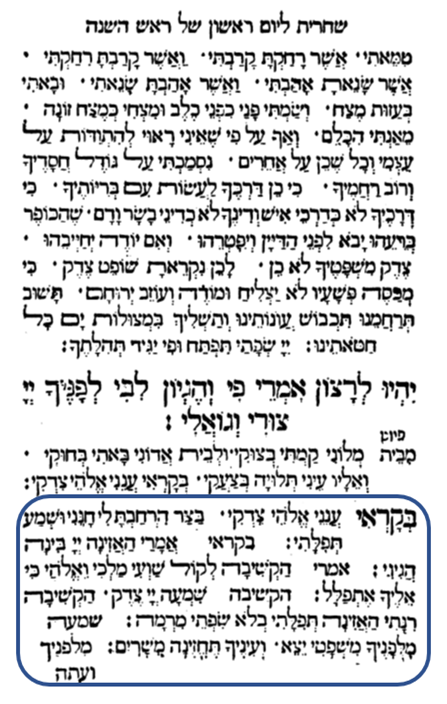

Figure 1: The Psalm verses in Seder le-yamim nora’im ke-minhag q”q Qarpentras, Amsterdam, 1759. They are preceded by Psalm 19:16, the common verse recited by every congregant before the beginning of prayers but also by the first stanza of a seliḥah by Moshe Ibn Ezra (in small letters) whose last line is the first half of the opening verse (Psalms 4:2) of the string of Psalm verses. Ibn Ezra’s seliḥah, widespread in North African liturgies (but also in Yemen), is not transcribed in Chants hebraïques:

מִבֵּית מְלוֹנִי / קַמְתִּי בְצוּקִי

וּלְבֵית אֲדוֹנִי / בָּאתִי כְחֻקִּי

וְאֵלָיו עֵינִי / תְּלוּיָה בְצַעֲקִי

בְּקָרְאִי עֲנֵנִי / אֱלֹהֵי צִדְקִי: תה' ד, ב

The set of Psalm verses performed in the morning services of both Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur includes:

תהלים ד, 2

בְּקׇרְאִ֡י עֲנֵ֤נִי אֱלֹ֘הֵ֤י צִדְקִ֗י בַּ֭צָּר הִרְחַ֣בְתָּ לִּ֑י חׇ֝נֵּ֗נִי וּשְׁמַ֥ע תְּפִלָּתִֽי׃

Psalm 4:2[1]

Answer me when I call,

O God, my vindicator!

You freed me from distress;

have mercy on me and hear my prayer.

תהלים ה, 3-2

אֲמָרַ֖י הַאֲזִ֥ינָה ׀ יְהֹוָ֗ה בִּ֣ינָה הֲגִיגִֽי׃

הַקְשִׁ֤יבָה ׀ לְק֬וֹל שַׁוְעִ֗י מַלְכִּ֥י וֵאלֹהָ֑י כִּֽי־אֵ֝לֶ֗יךָ אֶתְפַּלָּֽל׃

Psalm 5: 2-3

Give ear to my speech, O LORD;

consider my utterance.

Heed the sound of my cry,

my king and God,

for I pray to You.

תהלים יז, 2-1

שִׁמְעָ֤ה יְהֹוָ֨ה צֶ֗דֶק הַקְשִׁ֥יבָה רִנָּתִ֗י הַאֲזִ֥ינָה תְפִלָּתִ֑י בְּ֝לֹ֗א שִׂפְתֵ֥י מִרְמָֽה׃

מִ֭לְּפָנֶיךָ מִשְׁפָּטִ֣י יֵצֵ֑א עֵ֝ינֶ֗יךָ תֶּחֱזֶ֥ינָה מֵישָׁרִֽים׃

Psalm 17:1-2

Hear, O LORD, what is just;

heed my cry, give ear to my prayer,

uttered without guile.

My vindication will come from You;

Your eyes will behold what is right.

תהילים קמ"א, 2

תִּכּ֤וֹן תְּפִלָּתִ֣י קְטֹ֣רֶת לְפָנֶ֑יךָ מַֽשְׂאַ֥ת כַּ֝פַּ֗י מִנְחַת־עָֽרֶב׃

Psalm 141:2

Take my prayer as an offering of incense,

my upraised hands as an evening sacrifice.

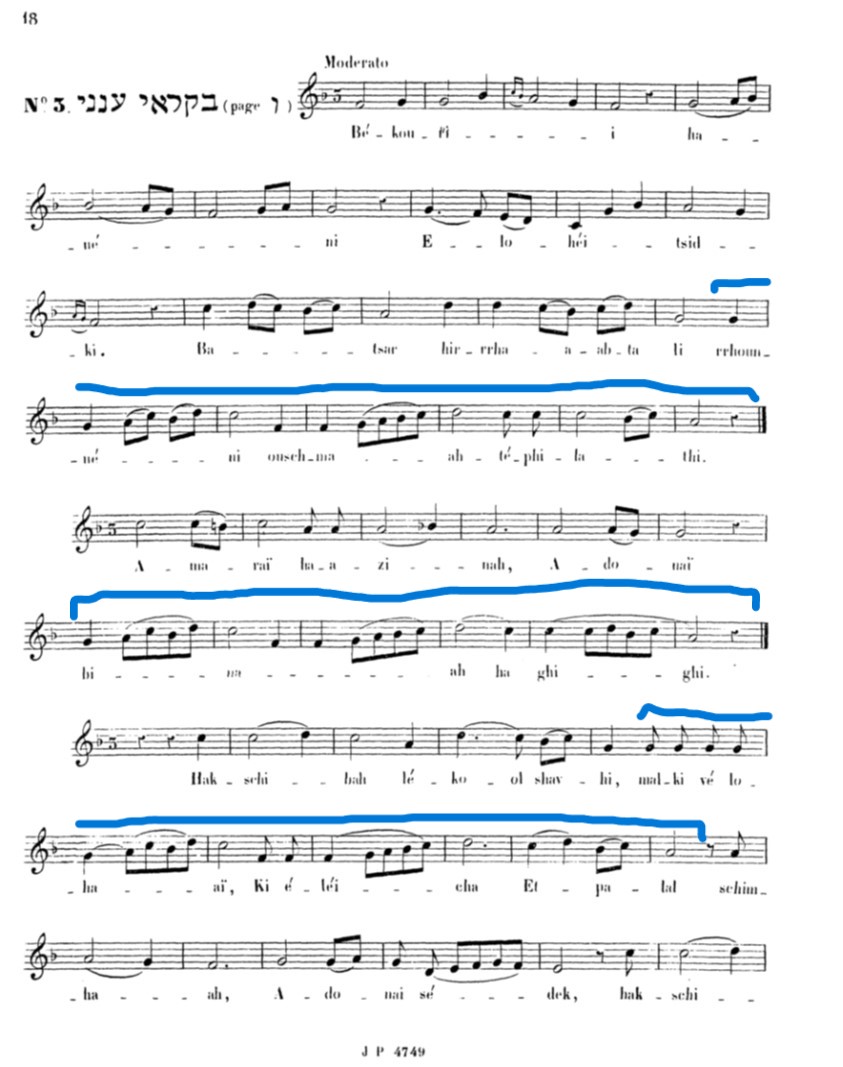

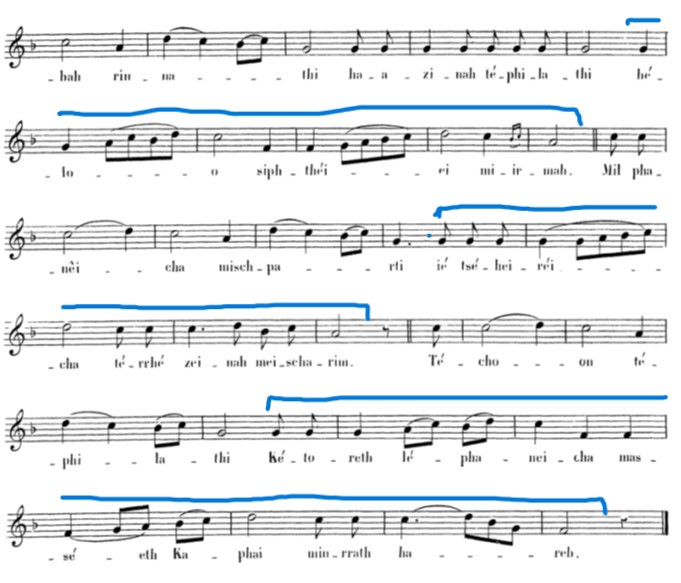

These verses convey, as expected from their selection as personal pledges by the cantor, the voice of an individual addressing God. Psalmist and cantor or shaliah tzibbur collide in their pledge to have their prayer be heard favorably. Prayers are described as songs, but also deemed to incense and sacrifices. Here is the musical translation of the piece as it appears in Chants hebraïques. Notice the peculiar transliteration of the letters ḥet (ח) as “rrh” or “rr”, ’ayin (ע) as “h” and fei (פ) as “ph”.

The musical structure of this piece is rather unique. Its compositional principle is somehow similar to Hebrew psalmody, whereas a musical phrase consisting of two melodic units with clear ending cadences is repeated with each verse. This musical phrase is expanded or contracted with additional motifs or extensions of the basic motifs pending on the length of each verse. However, in the case of the Provencal selection of verses, this psalmody principle applies mostly to the second unit that shows consistency in each verse (marked in blue in the score above), while the first one differs noticeably. This difference relates of course to the extreme variety in the length of the verses selected (e.g. ten words in Psalm 4:2 versus five in Psalms 5:2). Yet, there is more to that variability in the first unit than the need to expand or contract it due to different number of words. One could argue that the process of oral transmission within a very small community led to the weakening of a stricter pattern of psalmody, except for the more stable ending cadences. This decline in memory can be also observed in several details of the transcription, such as the forced setting of words under the music (see “malki velohai”) or the notation of arguably integral pitches from the melody as grace notes in the cadence under the word “mirmah”.

The piece is notated with fixed meter, a ternary one in this case, a feature extremely rare in this liturgical genre. However, psalmody’s rhythmic principle of having a longer duration for stressed syllables and a shorter one for unstressed ones is found throughout most of this piece. The modality of the piece is major, however all verses end on a “Phrygian” cadence on the third degree (A) except for the last one that descends to F, a “normal” major ending of the whole piece that would be most natural for a Westernized audience such as the Comtadin Jews. It is hard, however, to assess whether this final cadence was integral to the tradition or if this is an editorial “correction” made by the editors.

When did this liturgical unit of diverse Psalm verses enter Minhag Carpentras or by whom is unknown. Interestingly however, the first three out of our six verses (Psalms 4:2; 5:2-3) appear as an invocation preceding a piyyut in a codex attributed tentatively to Abraham ben Moshe Crescas of Provence (15th century).[2] Could this mean that versions of this selection of verses had different liturgical functions in the past?

While the frozen musical notation in Chants hebraïques is the only evidence we have of this liturgical text, the singing of this string of Psalms remained alive in the oral traditions of most Algerian Jewish communities. In almost all Algerian versions the Psalm verses are preceded by the singing of Aqum leshorer by R. Abraham ben Yaacob ibn Tawa (16th century), a piyyut unique to the Algerian liturgical traditions. The refrain of this poem is a contraction of the first verse of our string (first four and last two words of Psalm 4:2). From this refrain the transition to the string of Psalm verses is most natural. In the Algerian recorded versions of the string there is an additional verse, Psalm 5:4 and the title of Psalm 17 (Tefillah le-David) that is omitted in Minhag Carpentras, showing the variability of such unique insertions to the Jewish liturgical order.

The first Algerian version (Ex. 1), sung by Rabbi Meir Sulam and members of the Jewish community of Ghardaïa (Arabic: غرداية, in the Sahara in north central Algeria), was recorded in Israel on March 13, 2000 by the ethnomusicology workshop of Bar Ilan University and Renanot (Institute of Jewish Music) preserved at the National Library of Israel (see also here at 9:30). The performers mentioned that the piece is sung on the morning service of the second day of Rosh Hashanah before the prayer Nishmat kol ḥay, when the cantor rises to take his place at the bimah (podium) to lead the service. Rabbi Sullam opens by singing Aqum leshorer and flows naturally into the Psalm verses. What distinguishes this recording, intended as a reconstruction of an actual service, is its responsorial rendition in which the congregation repeats each verse in its entirety after the soloist, a rare technique in post-medieval Jewish liturgies

Rabbi Meir Zini (1921-2012), who officiated in Tiaret (Tahert) in North-Western Algeria and became the spiritual leader of the Wahrani (Oran) Jewish diaspora in France, recorded in 1966 a second version of the Psalm verses (Ex. 2). Like the previous version, the verses appear following, after another short insertion (Ve-‘al dal zeh), the piyyut Aqum leshorer. Rabbi Zini excludes, however, the last verse (Psalm 141:2).

A third version of the Psalm verses from Algeria (Ex. 3) also following Aqum leshorer is by a cantor identified in the catalogue of the National Library of Israel simply as “Zerbib.” It is highly possible that this version, apparently recorded in Paris c. 1967, is by Pinchas Zerbib (b. 1949), a distinguished cantor originally from Constantine in eastern Algeria who at the age of thirteen already officiated in the great synagogue in Nice.

Finally, Nathan and Youssef Cohen, two famous Tunisian Jewish singers, recorded the only known version of the Psalm verses in that tradition. This recording, with ‘ud accompaniment, was carried out in Tunis in May 1960 for documentary purposes (Ex. 4). Nathan Cohen is well-known to us for his profuse commercial recordings issued in Tunis and in Israel in the 1970s (see here for an example). A copy of this precious field recordings of the Cohens is preserved in the archive of the Jewish community in Paris and was shared with the National Library of Israel. Their version is also of seven verses as those from Algeria.

To conclude, the practice of using strings of Psalm verses (instead of whole Psalms) in the Jewish liturgy is common. What is unique to the practice documented in Minhag Carpentras is the use of Psalm verses as a pledge by the cantor (and, as the performance from Ghardaïa shows, the congregation) to have the prayers accepted. The persistence of this specific set of Psalm verses for the High Holydays in the communities of Algeria, Tunis and Provence calls for further research about these Mediterranean liturgical and musical connections.

______________________________

[1] Translations according to Jewish Publication Society, 1985

[2] See: Philippe Bobichon, Manuscrits en caractères hébreux conservés dans les bibliothèques publiques de France. Catalogues, Paris: Brepols, vol. V, manuscript 706, page 66.

References quoted

Granat, Yehoshua. 2016. "The “emissary of the congregation” as an individual in the early Reshut".U. Ehrlich (ed.), Jewish Prayer, New Perspectives (The Goldstein-Goren Library of Jewish Thought, Volume 20), Beer Sheba (Ben- Gurion University Press), pp. 79-99 (in Hebrew).

Idelsohn, Abraham Zvi. 1929. Jewish Music in its Historical Development. New York: Holt.

Source of Recordings at Sound Archive of NLI

Ex. 1: https://www.nli.org.il/he/items/NNL_MUSIC_AL990035675810205171/NLI

Ex. 2: https://www.nli.org.il/he/items/NNL_MUSIC_AL990002310180205171/NLI (Aqum: 33:27; Beqor’i: 37:17)

Ex. 3: https://www.nli.org.il/he/items/NNL_MUSIC_AL990035669350205171/NLI (3:55)

Ex. 4: https://www.nli.org.il/he/items/NNL_MUSIC_AL990002255020205171/NLI (31:22)

See on our website the project The Liturgical Music of the Provencal Jews (old Comtat Venaissin), includes an article by Darius Milhaud about the music on Comtat-Venaissin.