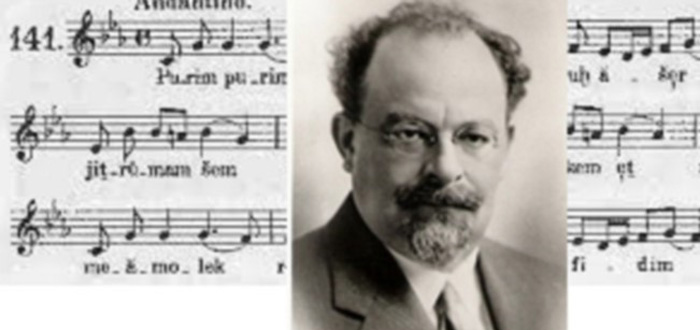

Idelsohn was born in Filsberg, Latvia (former Kurland or Courland) and began his study of Jewish music in Libau where he trained to be a cantor. He continued his education at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin and at the Leipzig Academy. Idelsohn served as a cantor at the Adat Jeshurun Synagogue in Leipzig, and in Regensburg and Johannesburg, South Africa before finally settling in Jerusalem in 1906. In Jerusalem, he began working as a cantor and music teacher at the Hebrew Teacher’s college. Idelsohn was greatly impacted by the diversity of the Jewish community living in Palestine, and embarked on a massive project to record their unique musical and linguistic traditions. To his end, Idelsohn was awarded a research grant from the Academy of Science in Vienna, along with a phonograph to use in his field work. In 1914, Idelsohn published the first volume of his seminal ten-volume work, Thesaurus of Hebrew Oriental Melodies, which was a comprehensive study of the Yemenite community in Palestine. Idelsohn was particularly interested in this community because he perceived the origin of their Hebrew pronunciation and musical heritage as dating back to the first century c.e. He argued that their musical and linguistic traditions were relatively uninterrupted by outside influence and change because of their migratory history and secluded geographical location. In the subsequent volumes of his collection Idelsohn surveyed the musical traditions of Babylonian, Perisan, Bukharian, Oriental Sephardi, Moroccan, German, Eastern European and Hassidic Jewish communities in Palestine and throughout the Diaspora. This immense project spanned over a period of 20 years, with the publication of the final volume in 1932. During World War I, Idelsohn served in the Turkish Army as a bandmaster in Gaza, returning to his research in Jerusalem at the end of the war in 1919. In 1922, he published the Hebrew song book, 'Sefer Hashirim,' which includes the first publication of his arrangement of the song Hava Nagila.

In 1924, Idelsohn was contracted to catalogue the Eduard Birnbaum collection of Jewish Music at the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. Shortly thereafter he was appointed professor of Jewish music and liturgy at HUC, a position he held until his health began to deteriorate in 1934. With access to the Birnbaum collection, Idelsohn wrote extensively on the historical development of Jewish liturgical and cantorial music. During his time at HUC, he published the last five volumes of the Thesaurus of Hebrew Oriental Melodies as well as two other seminal works, Jewish Music in its Historical Development (1929) and Jewish Liturgy (1932).

Idelsohn also made important contributions in the area of comparative musicological research with his work on the ties between Jewish and Christian liturgical music. Though less well known, Idelsohn also dedicated himself to the study of Near Eastern maqam systems, which is outlined in his work Die Maqamen der arabischen Musik (1913). Idelsohn’s enormous literary output, as well as his field recordings (which number over 1,000) laid the foundation for the modern study of Jewish musicology.

My Life: A Sketch by A.Z. Idelsohn

First published in Jewish Music Journal 2, no.2 (1935): 8-11, reprinted in the Abraham Zvi Idelsohn memorial volume of the Yuval Monograph Series 5:1986

I was born in the fisher-hamlet Phoelixburg, on the Baltic Sea, between Windau and Sackenhausen, Latvia. My father was Schochet and Baal-t’filloth in the district. When I was less than six months old, my parents moved to Libau, where, due to the efforts of Dr. Philip Klein, then Rabbi in Libau (later in New York), my father was appointed overseer of kosher meat in a non-Jewish butchery. In my early childhood my parents lived next to the “Chor-schul” and my father used to take me over to that cold, unheated house of worship. The chazzan was Abraham Mordecai Rabinovitz. His strong tenor-voice used to chill me; he had no sweetness in his voice. I remember the Congregation preferred to hear Zalman Schochet, though very old, or Orkin of the Zamet Synagogue. Little did I realize that Rabinovitz will later become my teacher. The above mentioned cantors had less voice than he, but much sweeter, and their singing was with more Jewish feeling.

From my father I learned to love the synagogal modes and “Zemiroth” as well as Jewish Folk-Songs. At home I received an orthodox education and appreciation for everything Jewish. I visited old-fashioned “Chadorim,” although there were many modern ones in Libau; my father wanted to implant within me the genuine Jewish piety. At the age of 12 years, I was sent to Lithuanian jeshivas, where I remained five years. During that period I acquired a knowledge of Jewish life. Upon my return home, I decided to take an examination at the Gymnasium and prepare for an intelligent profession. I secured a tutor and started studying.

Suddenly I felt an inner call for music and went to the above mentioned Rabinovitz, who accepted me in hi choir. There I remained for a half year, despite my father’s protest that I shall become a “chor-chazan.” His uncle never entered the Chor-shul because of the ban the ultra-orthodox Rabbis laid upon it when it was built.

Due to my brother-in-law, who came to visit us, but had to stop in Prussia, because he had no legal right to enter Russia, we journeyed there to see him. While in Memel (then Prussia), the idea came to me to go to Koenigsberh, to Edward Birnbaum. He accepted me and recommended me to the director of the Conservatory.

At the time I knew nothing of Birnbaum’s work, all I knew was that he was the successor to the famous Weintraub. I found him steeped in German music, his voice insignificant, his chazanuth unappealing and not Jewish. I visited him only a few times; he never instructed me and never showed me his collection.

After a few months I decided to proceed to London, according to my brother –in –law’s advice. Reaching London, I was advised to enter the Jewish College, but I had nobody to guarantee my upkeep during my stay there, so my meeting with Dr. M. Friedlaender was of no consequence. My parents wrote me, that Rabinovitz was willing to take m back, but I had no means to return. In my distress I turned to Israel Zangwill for help. He rcommended me to the Board of Guardians and secured my passage home. Upon Zangwill’s question, how can I return to Russia, where Jews were so maltreated, I answered that I prefer to be with my brothers even in a place like Russian than to live in a free country like England and assimilate.

Rabinovitz promised to instruct me in Chazanuth and in European music, and he kept his promise. During that year I again sand in his choir. He taught me a lot of things, such as sigh singing, theory, voice-training and the beginning of harmony. He acquainted me with the Chazanic literature of Weintraub, Sulzer, Lewandowski and others. He implanted within me an appreciation for good Jewish melodic taste and he gave me also an idea of classic music from the works of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, etc. At the same time I was an ardent reader of Modern Hebrew literature, from M. Ch Luzzatto’s poetry to the “Hashiloach” and the “Hador.” I became an admirer of the style and articles of Achad Haam, who became my guide and pathfinder in my confusion—the perplexity of a modern Jew.

My father, regarding me as a hopeless case, stopped interfering with my vocation. Considering that I learned everything possible from Rabinovitz, I left Libau in the spring of 1901 for Berlin to continue my musical education.

The day I arrived in Berlin I was accepted in the Stern’sches Conservatorium in the opera-class of Siedmann. The Director of the institution was Gustav Hollaender, a converted Jew who developed in me Germanistic, chauvinistic ideas. His brother, Victor H., who was also present, engaged me in the choir of the Charlottenburg Synagogue, of which he was the leader.

My first participation in the opera, however, ended badly; disgusted with the immoral conduct of the players, I gave up my studies and, influenced by Tolstoy’s ideas, I became a follower of them. I abandoned music, the Conservatorium and modern luxury and decided to become a farmer in Palestine. For this purpose I visited S. Bernfeld, who laughed at my fantasies and told me of the struggle of the poor colonists in Palestine. On the other hand, R. Brainin treated my differently; he wrote to a Baron Manteufel in Greece, who maintained a farm school, to accept me. Unfortunately his reply came too late. The whole summer I lived as a Tolstoian, until my meager resources were at an end. At that time there came to Belin Cantor Boruch Schor, who looked for singers. My colleagues who accepted Schor’s invitation, induced me to do likewise in order to earn something. Schor was already old and he had no voice at all; nevertheless his Jewish admirers clung to him enthusiastically. The compositions he gave us to sing were of very mediocre musical value, although some expressed the Jewish sentiment.

Soon the High-Holiday season arrived and I was confronted with the question of my existence. My friends recommended me to Frommermann, who maintained a school for cantors. He gave me a place in a Bavarian community. Brainin approved my action in becoming untrue to Tolstoianism.

My prearation in a Wentraub-Sulzer-Lewandowski repertoire was of no avail, there in Augsburg, I had to learn the South-German chazanuth, which is German, consisting of German melodies of the 17th and 18th centuries. On my way to Berlin I learned from Emanuel Kirschner, chazzan in Munich, that in Liepzig a chazzan was sought. I stopped there and was accepted; one of the Board was a disciple of Weintraub in Koenigsberg. There I would sing real Chazonus.

An old dream of mine was to study in the Leipzig Conservatorium, which I could now realize. I went to Prof. Jadassohn, a sincere Jew, born in Breslau from pious parentage. He was very friendly to me until his death in 1902.

While in Leipzig I studied harmony with Jadassohn, counterpoint with S. Krehl, composition with H. Zöllner and history of music with Kretzschmar, besides voice-training and piano. There I was able to attend the Gewandhaus concerts under A. Nikisch.

I met and married there a daughter of Cantor H. Schnieder. From Schnieder I learned the real Jewish sentiment in Chazanuth and melodic line. As a disciple of Achad Haam I detested the constant chase after Germanism, which I continuously heard in the synagogue song; even Lewandowski seemed Germanized. The life of the Jews in Germany, too, was Germanized. This was not only true of the Liberals, but also of the Orthodox.

At that time, the South-German Chazanuth was considered genuine Jewish. I, therefore, took a position in a Bavarian community, Regensburg, as Chazan and Schochet, but after two years I received a call from my relatives to come to Johannesburg, Africa, to become a chazzan there, which I accepted. I hoped to be able to live there a genuine Jewish life and to sing the Jewish song, but I soon realized my disappointment.

About the time the idea downed upon me to devote my strength to the research of the Jewish song. This idea ruled my life to such extent, that I could find no rest. I therefore gave up my position and traveled to Jerusalem, without knowing what was in store for me. In Jerusalem, I found about 300 synagogues and some young men eager to study Chazanuth. The various synagogues were conducted according to the customs of the respective countries, and their traditional song varied greatly from one to another. I started collecting their traditional songs. In the course of time the Phonogramm-Archives of Vienna and of Berlin came to my help. After a considerable time in the Institution in Vienna invited me to come and present the results of my studies.

As results of my collection and studies the following convictions became crystallized:

1) The Jewish song is an amalgamation of non-Jewish and Jewish elements, and despite the former, the Jewish elements are found in all traditions, and only these are of interest to the scholars.

2) The Jewish song is a folk-art, created by the people. It has no art-song, and no individual composers.

3) Composers of Jewish origin have in their creations nothing of Jewish spirit; they are renegades or assimilants, and detest all Jewish cultural values.

4) The few composers who remained within the fold have mostly corrupted the Jewish tradition with their attempts to modernize it, and have added very little toward genuine Jewish song.

I agreed to go to Vienna, where I was given two rooms by Prof. Exner to work out my records. I applied also for a subsidy from the Academy for the publication of my collection, which I called “Thesaurus of Hebrew Melodies” and prepared six volumes. For this purpose I had to visit the well-known anti-Semite, Prof. Warabazeck, who received me cordially, and due to his influence, the Academy granted mew a subsidy for my work. On the other hand the relation of the Vienna Chazanim was very unfriendly, almost hostile.

At the same time there took place the Zionist Congress in Vienna, and I met there Ch. N. Bialik, who induced me to write some Hebrew essays for his magazine ‘R’shumoth” which he intended to bring out, a request which I fulfilled.

The men friendly to me were Dr. M. Guedemann, Dr. M. Grunewald, Dr. Feuchtwanger—all Rabbis, also Dr. A Kaminka and A Stern (President of the Jewish Community). Very friendly was Prof. G. Adler of the University, who invited me to attend his glasses in Gregorian chant and to deliver some lectures. My work of the recorded songs and pronunciations I finished and submitted to Prof. Exner. It was published in the Academy Proceedings No. 175.

At that time a fight between the Hebraists and the “Hilfsverein” schools in Palestine was going on. I, though an employee of the “Hilfsverein,” decided for the Hebraists, although double salary was promised to my wife by Eph. Cohen. After eight months stay in Vienna I returned to Jerusalem and started my work in the Hebrew Schools.

From my “Thesaurus” only the first volume could be printed, for soon the world-war broke out and all cultural activities had to stop.

I was enlisted in the Turkish army, first as a clerk in the hospital, later as band master in the trenches in Ghaza, from which I emerged after the armistice.

In 1919 I returned to my teaching and research work. The Zionist Commission freed me partly from my work as teacher and I devoted this time for work on the “Thesaurus,” to write the Hebrew introductions, the first of which became very bulky, and I had to separate from it the Yemenite Poetry, which was late published separately under the title “Shire Teman.”

In 1921 I decided to go to Europe to publish my works. I took my family with me. I arrived for the Zionist Congress in Carlsbad, where Dr. V. Jacobsohn, then head of the “Juedischer Verlag,” bought my manuscripts of “Sepher Hashirim,” and Bialik encouraged me to write a history of Jewish Music, the first volume of which he published in the “D’vir,” the other four volumes remained in Ms. Up to date. Upon sending the second volume, Bialik wrote me... “Your first volume is still lying in our store, only a few copies are sold…we have no courage to print the second one.”

In Carlsbad I met also the head of the K’lal-Verlag in Berlin, who published my “Z’lile Haaretz” and “Z’lile Aviv”; there I met also B. Cahan (the owner of “Yalkut”) who brought out my “Sepher Hashirim” 1 and “Shire T’filloth”, 2nd edition. In Berlin in met Bejamin Harz with whom I arranged to publish my “Thesaurus” in Hebrew, German and English, and by the end of 1922 four volumes came out. During the year I was in Berlin, I materialized an old dream, I found a publisher to put out my JEFTAH, of which I wrote both the words and music and which was the first Hebrew opera ever written. Negotiations with the Oxford Press and other publishing companies were unsuccessful. After more than a year’s stay in Berlin my friends advised me to go to America on a lecture tour, which I did. Before that I lectured already in Vienna, Berlin, Breslau, Posen, Leipzig, London, Oxford, Amsterdam and in other places.

Upon my arrival in the U.S., I found Dr. and Mrs. De Sola Pool, Prof. and Mrs. Samuel S. Cohen, then in Chicago. It was due to their efforts that I was invited to catalogue the Birnbaum collection in the Hebrew Union College Library in Cincinnati and later was asked to teach at that college. They furthered my cause in various ways.

In 1924 I settled down in Cincinnati as Professor of Hebrew and Liturgy, as well as Jewish Music, but before that I toured the country lecturing, from coast to coast.

During my stay in Cincinnati, I added four more volumes to my “Thesaurus,” making it ten volumes. Them President of the College, Dr. Morgenstein, secured funds for the 5th and partly for the 6th volume, but the American Council of Learned Societies decided to grant me a subsidy for all the remaining volumes, and thus I was enabled to publish my “Thesaurus” in ten volumes in German and English, the first five volumes also in Hebrew.

From this work grew out several others: research in Liturgy, which I published in the “Thesaurus,” Vol. 3 and 4; research into the Poetry, which I published in the “Hator” and “Hashiloah” and separately in book form under the title “Shire Teman”; pronunciation of Hebrew, published in the “Hashiloah” and in the “Monatschrift” 1913, which was put out separately as a reprint; a Manual, published in 1926 by the Hebrew Union College—an extract of the four volumes of the History of Liturgy which Holt published in 1932. The Brotherhood ordered from me the “Ceremonies of Judaism,” and a these were put out in book form in 1929, a second enlarged edition in 1930, and a third edition in 1932.

My activity as teacher of singing and Chazan gave me ample opportunity to create along these lines. Already in 1908 I published in Jerusalem under my supervision two volumes “Shire Zion” for choir and solo, also a theory of music in Hebrew, “Torath Han’gina” (1910), and “Sepher Hashirim,” vol. 1, likewise several essays in various periodicals, and “Shire T’filla”1. While in America, considering the situation in which Judaism placed, I composed and published two Friday-evening Services and one Sabbath-morning Service for four part choir with organ accompaniment, according to the Reform ritual; “Jewish Song-Book,” two editions, the third edition is being delayed due to my illness. I also put out a Friday-evening Service for one voice with accompaniment.

In 1929 I was taken sick with coronary-vessel disease, and was laid up for six months. But in 1931 I had a paralytic stroke on my left side. This repeated several times, so that I could not teach any more, nor write, now move about, nor read much. The Board of the College granted me a pension, for the rest of my life. I can do nothing, but waste my time in reflection.