The Jewish Music Research Centre of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem mourns the passing of Rabbi Meir Eleazar Atiya on Shabbat Zakhor, March 16, 2019, after four years of severe illness and pain. No other date could have been more symbolic for his death, as this Shabbat marks the end of the bakkashot season according to the Moroccan tradition, of which Rabbi Atiyah was one of its main representatives of the past generation.

For over four decades, a deep personal and professional attachment linked me to Rabbi Atiya. He was for me a teacher and a research partner, and a figure that inspired great admiration and respect. Extreme humbleness characterized his widespread activities as a Torah scholar, poet, performer, teacher, archivist and editor. Without any structured institutional support, Rabbi Meir, as he was known among his disciples, single-handedly maintained and kept alive the Moroccan Jewish singing tradition in Israel against all odds. He was a transitional figure, having been born and raised in Rabat but then spent most of his life in Israel, where he received his rabbinical education. He perpetuated not only singing traditions but very specific liturgical practices from different Jewish communities in Morocco, in the face of their vanishing under the pressure of Israeli-Sephardic standardization.

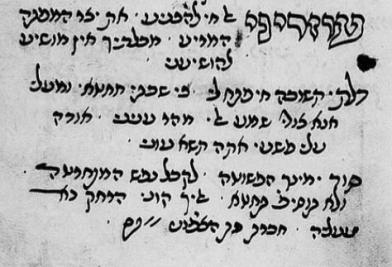

In spite of his variegated activities as a scholar, Rabbi Atiya was known and will be remembered as Moroccan Jewry’s foremost paytan, an expert in the religious poetry sung as part of the liturgy, in paraliturgical events as well as in ceremonies celebrating the stages of the life cycle, such as circumcisions and weddings. He was not the most outstanding in terms of virtuosity, rather his performance style was characterized by his extreme precision, deep understanding of the relations and differences between the Moroccan Arab and Hebrew traditions of Andalusian music, and by his profound knowledge of the Hebrew language and the hermeneutics of sacred poetry. Above all, his capacity as a pedagogue enabled him to be at the forefront of those passing the tradition to a new generation of Israel-born Moroccan piyut singers. On many occasions, he carried out this enormous effort of transmission on a voluntary basis, in synagogues and community centers throughout Israel, travelling long distances at his own expense. At times, announcements about his classes were passed orally, without formal advertisement. His monumental mid-1980s recording project of twenty cassettes, comprising the entire bakkashot repertoire according to the predominant southern Moroccan Andalusian Hebrew tradition based on the compendium Shir Yedidut (first edition Marrakesh, 1921), became as much a major pedagogical tool as it would a resource for ethnomusicological research. The twenty cassettes are now accessible via the Sound Archive of the National Library of Israel.

Rabbi Atiya crossed the boundaries between “the field” and “academia,” those two elusive poles of ethnomusicological research. Our personal bond was from its inception one of partnership, of sharing knowledge and resources, and challenging the power relationships that once characterized the gap between the “ivory tower” and “the informants.” One of Rabbi Meir’s crowning achievements, Me’ir Hashahar (2 vols. Givat Olga, 1995, 1023pp.), the complete compilation of Moroccan Andalusian repertoire in Hebrew, was made possible in part by our shared research at the Institute of Microfilmed Hebrew Manuscripts at the National Library of Israel. He was also my partner in curating Sacred Music of the Moroccan Jews, released by Rounder Records in 2000, an edition of the historical Moroccan Jewish recordings of made by Paul Bowles and housed in the Library of Congress.

One of Rabbi Atiya’s last public appearances was in the framework of the ‘Oud Festival, on November 11, 2018, in a program dedicated to the memory of Rabbi David Buzaglo z”l, produced by the JMRC. Obviously in a failing state of health, he still graciously accepted my invitation to appear. Insisting always in calling me “Professor Edwin,” he opened his remarks with his characteristic and unmistakable humbleness by saying that he had “nothing to add in face of the elder paytanim present in the public.” Having said that, he elaborated on his ground-breaking research of several decades dedicated to collecting, editing and punctuating the scattered poetry of Rabbi David Buzaglo, which Rabbi Atiya published in another of his monumental projects, Shirei Dodim Hashalem (Givat Olga, 1987, 426pp.)

Complete panel from the 'Oud Festival, November 11, 2018 (Hebrew)

Much remains to be said about Rabbi Atiya and his contributions. A more detailed assessment of his achievements is certainly due in the future. For the moment, as we mourn his passing at a relatively young age, we can celebrate his unique personality, which bridged Arab-Muslim and Arab-Jewish cultures without unnecessary clichés. The recognition of his work by his country of birth by no less of a figure than the King of Morocco, Mohammed VI, is a testimony of the pertinence of his art and its import beyond the Moroccan-Jewish community. A short documentary made about him (below, Hebrew), at the initiative of the Invitation to Piyut website, is a touching memento of a figure whose loss is certainly going to be felt.