The Baqqashot (petition) is a religious practice maintained by several Jewish communities. It consists of gatherings that occur early on Sabbath morning, from 2-3 a.m. until the Shaharit prayer, in which the participants communally sing various piyyutim, which are titled Baqqashot. The practice developed, for the most part, in two geographical areas: the area of Allepo in Syria, and subsequently in other Syrian and Palestinian communities; and in Morocco. The Baqqashot are practiced during the winter, from Sukkoth to Passover, beginning on Shabbat Bereshit and until Shabbat Zekhor (the one prior to Purim) in Moroccan communities, and until Shabbat Hagadol (the one prior to Passover) in Allepian communities.

Some of the main themes of the Baqqashot piyyutim are: the Kabbalistic perception of divinity; the meaning of the time of day in which the Baqqashot are sung (early morning); and the holiness and the value of the Sabbath.[1]

The Origins of the Baqqashot

Origins of the Baqqashot custom[2] are not fully known, but it is known that poems of the baqqashah type were included in Sephardi prayer books even before the final expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. Moreover, nocturnal study and prayer, which are central components of the Baqqashot, were customary in Spain and in the Land of Israel during the Middle-Ages.

It may be assumed that the Baqqashot as we know them today originated among cabbalistic circles in Safed in the sixteenth century. The cabbalists of Safed ascribed prime importance to the singing of piyyutim. Their repertoire included poems written by the poets of the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of Hebrew poetry in Spain (10th to 13th centuries), and these formed the basis of and inspiration for the piyyutim written by Sephardi poets, many of them cabbalists, in the Land of Israel and the neighboring countries from the sixteenth century onwards. The most prominent among them was Rabbi Israel Najara, whose piyyutim form an important part of the Baqqashot to this very day; his book, Zemirot Yisra’el (Songs of Israel) was published in three editions: Safed 1587; Salonica 1599/1600; and Venice, 1600. Zemirot Yisra’el is exceptional in that the piyyutim are arranged according to the maqamat (musical modes) in use in the court music of the Ottoman Empire during the author’s lifetime. Moreover, the lehanim (plural of lahan, tune or melody) to which Najara required his piyyutim to be sung are borrowed from the musical culture of the Sephardi Jews of Spain (tunes of Judeo-Spanish songs) and of the peoples of the region: Arabic, Turkish, Greek and Persian tunes. In Najara’s book, and in those of his followers, the directions indicating the maqam and the lehanim to be applied for the performance of the song are provided in the headings of the piyyutim. The use of Turkish or Arabic maqamat and melodies of the surrounding musical cultures became embedded in the Sephardi liturgical and paraliturgical tradition, and have remained a main trait to this day.

Jerusalem-Sephardi Style

The adoption of the maqam principle as the basis of the religious music of the Sephardi Jews in the Ottoman Empire, from the sixteenth century until now, led to the crystallization of liturgical traditions and piyyut performances that conform to this musical system. The most common of these liturgical styles, known as the Jerusalem-Sephardi style, is based mainly on Arabic maqamat rather than on the Turkish maqamat employed by Najara. This major characteristic of the Jerusalem-Sephardi Baqqashot is the result of developments in the musical culture of the Middle East in general, and in Jerusalem in particular over the past two centuries or so. The main development was the gradual collapse of the Ottoman Empire since the end of the nineteenth century. As a result, the influence of the Ottoman/Turkish musical culture, which up to then had been predominant in the Sephardi Jewish liturgy and piyyut singing in the Middle East, went into decline, and that of Arabic, and particularly Egyptian, music, grew stronger.

Another factor in the development of the Jerusalem-Sephardi tradition was the immigration of several of the spiritual leaders of the congregation of Aleppo to Palestine, among them some of the outstanding cantors and payytanim of that community. The Aleppo community possessed a distinctive tradition of religious music derived from the heritage of Rabbi Israel Najara and from local Arabic music, which the Arabs themselves considered to be particularly original. One example of the central role of Arabic music in the music of the Jews of Aleppo is the ‘maqam chart’ that specifies the principal maqam of the Morning Prayer of every Sabbath in the annual cycle. In 1901, the Jewish immigrants of Aleppo in Jerusalem established the Ades synagogue, which soon became a center of religious music for all the Jerusalem Sephardim and members of other Middle Eastern Jewish congregations (such as the Persian, Bukharian, Iraqi, Kurdish and Yemenite congregations).

The final crystallization of the Jerusalem-Sephardi tradition was hastened by the invention of the gramophone at the end of the nineteenth century. The ability to record music and to spread it widely greatly increased the diffusion of the new Arabic music from Egypt and Syria during this period. The members of Jewish congregations in the Middle East were also exposed to the new musical styles heard on records and, later, on radio and in films. The accessibility of the modern Arabic music spread by new media hastened its adoption by Jews as the basis of the music of piyyutim and prayers.

The music of the Jerusalem-Sephardic Baqqashot is, therefore, based on two basic principles that developed simultaneously among Sephardi Jews in Ottoman lands: the singing of piyyutim in the synagogue on the early Sabbath mornings; and the organization of the musical content of this event in accordance with the principles of the Arabic maqam. As a result of its historical development, the Jerusalem-Sephardi repertoire, including the Jerusalem Baqqashot, consists today of a combination of two musical strata: an ancient stratum, consisting of the vestiges of Ottoman Turkish music still echoed in the prayers and piyyutim; and a more modern stratum, the urban Arabic musical culture which crystallized in the Middle East at the end of the nineteenth century, which is now the dominant component of the Jerusalem-Sephardi tradition.

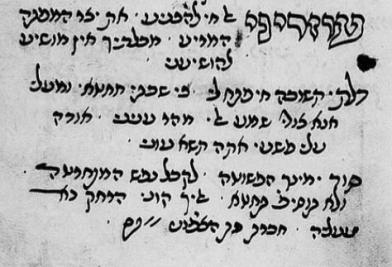

Baqqashot texts in the Jerusalem-Sephardi Tradition

The tradition of the Baqqashot as performed today in the Jerusalem-Sephardi tradition is based on 'Sefer Shirei Zimra Ha-Shalem Ve-Sefer Ha-Baqqashot Le-Shabbat' (The Complete Book of Songs and Book of Baqqashot for the Sabbath), edited by Haim Shaul Abud and published in Jerusalem in 1931. Over the course of the twentieth century this collection of piyyutim, which was based on various previously printed collections, became required reading for the cantors who performed in the Jerusalem-Sephardi style.

The sources of the piyyutim in this book are varied: they include piyyutim from the Golden Age in Spain (10th-13th centuries); the piyyutim of Rabbi Israel Najara and his followers in the Ottoman Empire (16th and 17th centuries); and piyyutim of later local authors (from the 18th to the 20th centuries), including important rabbinical figures from Aleppo. The identity of some of the authors is unknown. In alphabetical order, the known authors of the piyyutim in this collection are:

Abadi, Mordecai; Abadi, Ya’akov; Abud, Haim Shaul; Antebi, Raphael (“Tabush”); Attia, Ezra; Attia, Yehuda; Azkari, Elazar; Dayan, David; Ibn Ezra, Abraham; Ibn Gabirol, Salomon; Caro, Joseph; Katzin, David; Katzin, Yehuda; Laniado, Shelomo; Lavi, Shim'on; Labaton, Mordecai; Lopes, Nissim; Maimin, Abraham; Mizrahi, Asher; Morsaya, Shelomo; Najara, Israel; Sasson, Eliyahu; Siton, Abraham; Siton, Joseph; Siton, Menasheh; Sweid, Ezra.

Baqqashot Music in the Jerusalem-Sephardi Tradition

The Jerusalem-Sephardic Baqqashot is a musical event that lasts for 4-5 hours. In order to make it more interesting, the participants are divided to two groups, which sit facing each other, and maintain a sort of singing competition between them. Both groups include adults and young people, soloists, and a singing leader. After a piyyut or a sequence of piyyutim is completed, the next group continues.

As mentioned above, the principal musical element in the Jerusalem-Sephardi Baqqashot is the maqam. The repertoire of Baqqashot contains two musical genres. One genre consists of rhythmic melodies with a steady beat, sung by the congregation, and usually employed in the performance of the piyyutim.

The second genre includes music without a clear beat that consists of independent pieces known as petihot (sing. petiha, lit. openings) or short musical passages interpolated in the course of the singing of the piyyutim, all performed by solo singers. The petihot are not piyyutim; they are selected verses from the Book of Psalms, other books of the Bible, or the Mishnah (Oral Law). Since all of the Baqqashot in the Jerusalem-Sephardi style are based entirely on the principle of the maqam, the name of the maqam in which the lahan is performed, as well as the name of the lahan itself, appears in the title of every piyyut; in the petihot, the maqam in which each verse or group of verses is performed is indicated next to the text.

In the course of the event, sequences of piyyutim are performed whose lehanim belong to a maqam family. Between sequences of piyyutim, the petihot are sung by one or more solo singers, in a kind of improvisation. The petihot generally begin with the maqam of the previous sequence, and conclude with the opening maqam of the next sequence. The conclusion of the event is always sung in the maqam of the next Sabbath service. This concluding portion of the Baqqashot always includes the piyyutim 'Yedid Nefesh' (Friend of My Soul) and 'Agadelkha' (And I Shall Praise Thee), as well as the passages 'Avarekh' (I shall bless) and 'Rabbi Hanania,' followed by Qaddish, which concludes the whole of the service.

Moroccan Tradition of Baqqashot

The main difference between the Moroccan Baqqashot and those of the east is that in the Moroccan tradition, each of the 22 Sabbaths in which the Baqqashot are performed has its own repertoire of piyyutim. Furthermore, the Moroccan Baqqashot are performed by a group of trained paytanim, and led by a head paytan. Here, the congregation only joins at specific places. Usually the main paytan begins the singing, and the rest of the paytanim join him. The head paytan will determine which piyyutim will be sung on each Sabbath as well as who will sing the complicated solo parts.[3] Unlike the Allepian Baqqashot, the singing in the Morrocan Baqqashot is generally less congregational, but rather is performed by professional paytanim and includes both solo and choral parts.

Moroccan Baqqashot customs began to form during the 18th century, and developed greatly during the 19th century. Since its publication in 1921, the book Shir Yedidot, an anthology of piyyutim, has become the main text for Baqqashot singing in the Moroccan tradition.[4] In it one can find a structured Baqqashot service. While the majority of the piyyutim in Shir Yedidot were written by North African poets, the book also includes piyyutim written by the poets of Spain as well as by Israel Najara. They are ordered according to the order of the Sabbaths and each Sabbath has its own Nuba[5] (a complicated musical structure in Andalusian music) in which all of the piyyutim of that Sabbath are sung.

The sources of the Baqqashot piyyutim's melodies vary, but most of them come from the Arabic-Andalusian tradition, with some eastern and even European influences. However, there are also unique Baqqashot melodies. Older sources of the Baqqashot are melodies from the 17th and 18th century that were set to ancient piyyutim. These melodies come from local sources as well as from the Palestine and Turkey regions, and were transmitted by Meshulahim (Jewish emissaries from the Land of Israel). Another source of the Morrocan Baqqashot melodies are modern 20th century folk melodies from Egypt and other Middle-Eastern countries, which were adapted by the paytanim according to the contrafactum technique, in order to appeal to a younger audience.[6]

Due to the immigration of the majority of Moroccan Jews to Israel, and the difficulties of assimilation in the new country, the Moroccan Baqqashot practice, like other parts of the Moroccan Jewish tradition, suffered a decline during the 20th century. Rabbi David Buzaglo, who immigrated to Israel in 1965, has done immense work in order to revive the Moroccan Jewish traditions, including the singing of Baqashot.

Baqqashot Today

Currently the Aleppian Baqqashot in their original settings are performed in the Ades synagogue and the Mousayof synagogue on the Sabbaths and in the Har-Tzion Synagogue in Jerusalem on Thursdays. Moroccan Baqqashot are performed today in various synagogues across Israel, in towns and cities such as Kiryat Shemona, Ma'alot, and Dimona. Ashkelon and Ashdod are particularly important places for the practice of Moroccan traditions in the synagogue, as Ashdod's mayor Yehiel Lasri is himself a paytan.

The Baqqashah

The Baqqashah (Baqqashot in singular form) signifies two structures of piyyuutim:

The first is a large-scale poetic composition written in a highly stylized manner, which deals with profound philosophical themes. It was meant to be said by an individual, and does not have an organized strophic structure or a meter. This type of Baqqashah was created by Rabbi Sa'adiah Gaon (882/892-942),[7] who included two long Baqqashas in his siddur. Following him, this kind of Baqqasha was written by others, including Solomon Ibn Gebirol and Yehuda Halevi.

The metered Baqqashah is a piyyut of the Seliha kind. It has a personal tone, and deals with pleading for forgiveness. This Baqqasha was created in Spain, and is metered and rhymed. Examples of this Baqashah are: Kol Broay M'ala Vmata, by Ibn Gebirol[8]; Adonai, Negdekha Kol Taavotay by Yehuda Halevi.

The Baqqashah is a unique piyyut genre associated with the

Selihah. It has a more personal tone, including sometimes pleadings for forgiveness by the individual. The Baqqashah is unique to the religious Hebrew poetry of medieval Spain, it is usually scanned in quantitative meters and consists of simple rhyme patterns. Examples of this type of Baqqashah are:

Kol Beruei Ma'ala Umata, by Shlomo Ibn Gabirol

[8]; Adonai,

Negdekha Kol Taavotai by Yehuda Halevi.

[9]

Links:

Sources:

1. Marks, Essica. Booklet of the JMRC CD Song of Dawn. Jerusalem: Jewish Music Research Centre, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2007.

2. Sasson, Amnon. 'Baqqashah.' An Invitation to Piyut.

3.Bakshi, Meir. 'Shahar Avakshekha- Al Shirat Habaqqashot Bemasoret Sefarad Yerushalayim.' An Invitation to Piyut.

4. Ftaya, Hana. 'Dodi Yarad Legano - 'Al Shirat Habaqqashot Shel Yehudey Maroco.' An Invitation to Piyut.

5. Marks, Essica. 'Mavo Le'olam HaPiyut VeHamusikah Bemasoret Yehudei Maroco.' An Invitation to Piyut.

6. Yayama, Kumiko. 'HaRekah HaHistori Shel Shirat HaBaqqashot.' An Invitation to Piyut.

7. Amzaleg, Avraham. 'Shir Yedidot VeShirat Habaqqashot.' An Invitation to Piyut.