El Shokhen Shamayim, Gabriel Sayag, Wahran (Oran), recorded 1929

El Shokhen Shamayim - A Recorded Pearl of Andalusian Hebrew Music from Algeria Recovered

Joel Bresler’s magnificent collection of 78 rpm recordings of Sephardic music is well-known to all those interested in this repertoire. Lately his collection has been digitized professionally in full at the George Blood facilities in Philadelphia, a world leader in the digital recovery of historical recordings. Among these recordings there are numerous 78 rpm disks that were not digitized before and one of these items is our song of the month. Bresler’s website will offer extended audio from his collection in a future redesign. Meanwhile, we hope you enjoy this preview.

The Algerian Jewish singer Gabriel Sayag recorded the piyyut El shokhen shamayim harheq kol pesha for the Gramophone Company in Tunis on July 3, 1929 (see below). The present record, pressed in Paris (K-4195), is one of the many products of multiple cross-cultural interactions characteristic of modern North African Jewish music. The other side of our record contains another Andalusian Hebrew song, La’ad aromimkha malki. Crossing boundaries between Jews and Muslims, between Jews from the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, and between Maghrebi and colonial Europeans, this recording brings to life a unique sonic moment that precedes the dissolution of Jewish life in Algeria and the weakening of the venerable Western Algerian Hebrew Andalusian repertoire.

El shokhen shamayim, Gramophone, Tunis, 1929

Not much is known about Gabriel Sayag. He appears on the record label as “cantor of the Great Synagogue of Oran,” while the name of his piano accompanist is not mentioned. We tentatively identify this cantor as Joseph Gabriel Sayag (or Sayagh), born in Wahran (Oran) on March 27, 1905 and died in 1942 apparently of pneumonia. Although relatives of him from Paris mentioned that he recorded songs in Arabic, no such items have so far resurfaced. Sayag was a young singer of twenty-four years when he recorded for Gramophone on July 3, 1929.

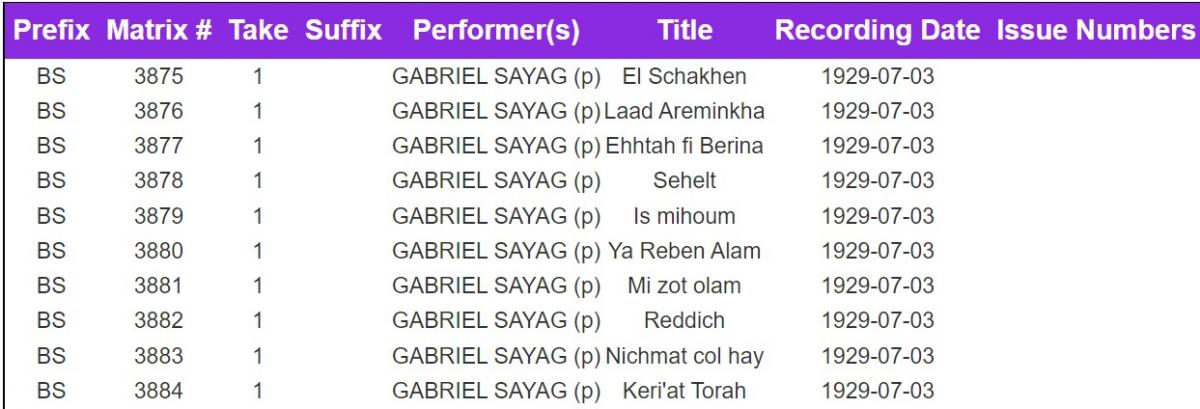

Dr. Allan Kelly’s database of Gramophone Records lists ten entries for Gabriel Sayag (with very distorted Hebrew titles):

These recordings are very rare. In addition to Bresler’s record there is one more available at the Jacob Michael Collection that was donated to Hebrew University and belongs now to the Israel National Library (Gramophone K-4197: Ismehou/Ya rebon alam = BS 3879 and 3880 in the aforementioned list.)

Sayag evidently sings El shokhen shamayim based on the version appearing in the second, expanded edition of Shivhei Elohim (Wahran, 1880, p. 133; first published in 1856) the main late-19th century compendium of religious Hebrew poetry from Western Algeria. As with many other items in this compendium, El shokhen shamayim (acrostic Abraham) has its origins in the Hebrew poetry of the Eastern Mediterranean, most probably in Turkey. This is as attested by its early printing (very truncated and with a different acrostic) in the compendium Siftei Renanot (Saloniki, 1859). The title of the song in this compendium is Nakşi sema’i [makam] Ushak, a reference to the Ottoman music genre and musical mode used by the singers. The song appears later on in a variety of Eastern sources, notably Sefer haShirim (Baghdad, 1906) and Shirei Yisrael be-Eretz ha-Qedem (Istanbul, 1921), the ultimate printed collection of sacred Hebrew poetry set to Ottoman art music.

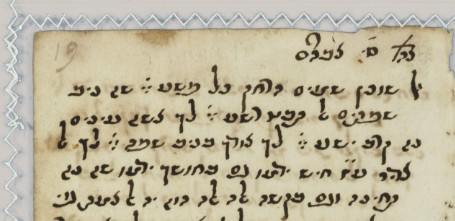

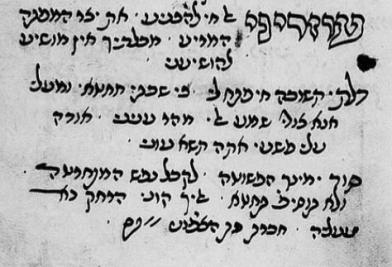

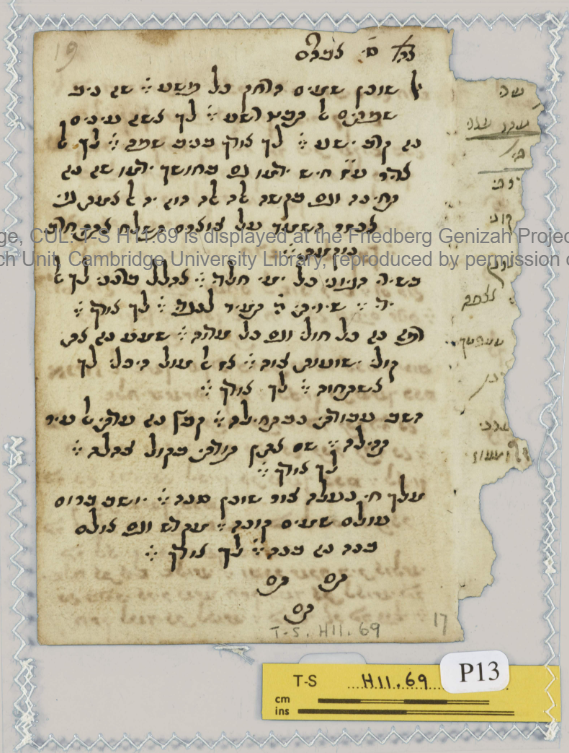

All these and several other printed versions of our piyyut differ from one another (see more details below). However, there is a manuscript version that appears to be the oldest one extant, located in the Cairo Genizah Taylor-Schechter collection of the University of Cambridge, Ms. T-S, A-K, H11.69, fol. 13r. This version is the most poetically consistent one, therefore closer to the time and place of the still unidentified poet Abraham. It includes five stanzas of three rhyming lines each in the syllabic meter (6+5 syllables per line) characteristic of post-17th century Ottoman Hebrew poetry. In addition, the song contains a very irregular refrain to be sung after each stanza, an indication that the song was probably set to a Turkish musical piece whose refrain included non-textual syllables. This is most clear in the peculiar words “Eloha, eloha hu” that Sayag sings as “Allah, Allah hu.”

Cairo Genizah, Taylor-Schechter collection of the University of Cambridge, Ms. T-S, A-K, H11.69, fol. 13r

Transcription by Prof. Tova Beeri:

בה' ס' אברהם

אל שוכן שמים / הרחק כל פשע

שא ניב שפתים / אל תבט רשע

לך אשא עינים / נא קרב ישע

לך אודך בניב שפה לך אל אדיר

ע[בודה] ז[רה] חיש ידמו

גם בחושך ידמו

שא נא תחינה וגם בקשה אלה אלה הוא

יה אל אמת גוי השמד

על צוארם תשלח אתה חרב נוקמת

בשירי הגיוני / כל ימי חלדי

אהלל ברנני / לך אל ידי

שיויתי ה' / תמיד לנגדי לך אודך

רפא נא כל חולי / וגם כל מדוה

שמע נא את קולי / ישועות צוה

אז אל מול היכלי / לך אשתחוה לך אודך

השב עבודתי / כבתחילה

קבץ נא עדתי / אל עיר תהילה

שם אתן תודתי / בקול צהלה לך אודך

מלך חי נעלה / צור שוכן סנה [צריך להיות 'נעלם' בשביל החרוז, אבל רשם 'נעלה']

יושב ברום עולם / /שמים קונה

מקדש וגם אולם / מהר נא בנה לך אודך

The Genizah manuscript, an Ottoman Hebrew mecmua (a compilation of songs by different poets for musical performance), lacks the musical instructions characteristic of these collections (unlike the aforementioned printed version from Salonika in Siftei Renanot). One of the main figures represented in this collection is Avtaliyon ben Mordecai, a disciple of Israel Najara. Therefore, the manuscript can be cautiously dated to the second half of the 17th century or early 18th century.

How and when this Ottoman Hebrew song reached the Maghreb is hard to know but all the evidence points to the last third of the 19th century. Besides Shivhei Elohim our song is included in the Moroccan Andalusian Hebrew compilations Roni veSimhi (Vienna, 1890) and Shir Yedidut (Marrakesh 1924; see the latest revised edition by tha late Rabbi Meir Eliezer Atiya, Shir Yedidut haShalem, Jerusalem 2000, parashat Lekh Lekha, p. 130) a compendium used for the singing of Moroccan baqqashot. Rabbi Atiya attributed the poem to R. Abraham Koriat of Tetuan (d. 1806) without any evidence, as previous editions of Shir Yedidut do not include such an attribution. Our song is also included in the Tunisian compilation ‘Et Laledet (Tunis, 1911).

As mentioned above, the text of our song in all these sources is not homogeneous. For example, the version from Sefer haShirim of Baghdad has an entirely different last stanza in comparison to all other versions. While the refrain in the Genizah and Eastern versions starts with 'Lekha odkha beniv safa' (You I will praise with words of my lips) the North African versions read 'Az odkha beniv safa' (Then I will praise You with words of my lips). Interestingly, the Moroccan version changes the half line 'Eloha, Eloha Hu' (sung as noticed above as 'Allah, Allah hu') from the refrain with the words 'Yah ram le’amo.' Can this be an intentional attempt to de-Islamicize the text? Finally, in the last hemistich of the last line of the final stanza, preceding the last iteration of the refrain, the wording changes in almost every source as follows:

| Cambridge, T/S A-K, H11.69 | Shivhei Elohim | Shirei Yisrael beEretz haQedem 1921 | Shir Yedidut 1924 | Shir Yedidut haShalem 2000 |

| מהר נא בנה | בנה בנה | בנה גם בנה | בנה גם בנה | בנה, יה, בנה |

Sayag sings the first stanza and the refrain as a unit, exactly as printed in Shivhei Elohim (see appendix of sources). The skillful pianist accompanies him in unison in the traditional Andalusian style from Western Algeria. While the music of the opening stanza is clearly based on motives from the Raml Maya mode, the refrain’s melodic movement and rhythm departs from recognizable patterns of Western Algerian music.

The impressive consistency in the performance of this piyyut in Wahran can be heard in two additional field recordings by two prominent figures of Waharani hazzanut. The first one is a historical gem by Samuel Cohen, rabbi, cantor and composer of the Great Synagogue of Wahran from the late 1930s to 1962, recorded in the late 1950s. Notice that Cohen adds a coda in Arabic to his recording, emphasizing the name of Allah and perhaps also having in mind coda of the piano in the recording by Gabriel Sayag. The second recording, made in Israel in 1999, is by Daniel Ashkenazi a representative of the last generation of Wahrani cantors, a disciple of R. Samuel Cohen and son of R. David Ashkenazi, chief Rabbi of Wahran, who officiated jointly with Cohen.

El Shokhen Shamayim, R. Samuel Cohen, Great Synagogue of Wahran (Oran), late 1950's

El Shokhen Shamayim, Daniel Ashkenazi, Israel, 1999

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Eric Karsenty for his cooperation in gathering information on Gabriel Sayag and retrieving additional performances of the piyyut; to Sarah Cohen for locating the piyyut in the Cairo Genizah online; to Prof. Jonathan Glasser and his research associates for their analysis of the tune; to Prof. Tova Beeri for the transcription of the Genizah text; to the Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society for making the digitization of Genizah manuscripts accessible to the public; and of course to Joel Bresler for providing the original recording.

Download printed versions of El Shokhen Shamayim