Born in Hungary on 5 March 1932 to a characteristically assimilated Hungarian-Jewish family and having survived the Holocaust (a subject he rarely commented on), André Hajdu enrolled after the war at the prestigious Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest. There he studied under Endre Szervánszky and Ferenc Szabó (composition), Erno Szégedi (piano) and Zoltán Kodály (ethnomusicology). As a disciple of Kodály, Hajdu developed a deep interest in ethnography, the relation between folklore and contemporary composition and in pedagogy. He was involved in a research project about Gypsy music and published several articles in Hungarian on this subject. His Gypsy Cantata on poems of Miklos Randoti won first prize at the Warsaw International Youth Festival (1955). All these interests were to accompany his work throughout his career.

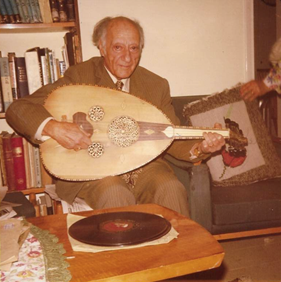

In the aftermath of the failed Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Hajdu left his home country. He settled in Paris, a site favored by many Hungarian dissidents, and continued his studies at the Paris Conservatoire under illustrious teachers of the post-war generation, such as Darius Milhaud and Olivier Messiaen. From 1959 to 1961 he taught piano and composition in Tunisia. His Diary from Sidi-Bou-Said for solo piano (1960) is a testimony to this experience.

Upon his return to Paris, Hajdu gradually immersed himself in Judaism and started to observe Jewish religious practices. At the same time, he mingled in Paris’ intellectual circles and met, among others, Prof. Israel Adler, then Judaic a librarian at the National Library in Paris. In the early 1960s Adler returned to Israel to found the Department of Music at the Jewish National and University Library and the Jewish Music Research Centre. In 1966, Hajdu immigrated to Israel and settled in Jerusalem, where he joined the JMRC upon Israel Adler’s invitation. He worked jointly with Yaacov Mazor in the research of Hassidic and klezmer music in Israel, a fruitful collaboration that led to several innovative studies and seminal JMRC publications in these two fields. Hajdu has to be credited with the concept of “niggunei Meron” to refer to the specific klezmer repertoire performed at the tomb of Rabbi Simeon Bar Yochai during the Lag B'omer celebrations on Mount Meron, in the Upper Galilee.

Also upon his arrival to Israel, the Rubin Academy of Music at Tel-Aviv University (today the Buchman-Mehta School of Music) hired him and he taught there from 1966 to 1991. In 1970, he joined the faculty of the newly created Department of Musicology at Bar-Ilan University where he taught as a full professor until his retirement. He was head of the department and also co-founded the Ph.D. program in composition, the first one in Israel.

In his prolific creative work, Hajdu became deeply interested in Jewish topics, not necessarily by employing or quoting folkloric themes that he researched, but rather by interpreting through music, as an exegete, basic Jewish texts, such as the Mishnah, the Talmud and the philosophical books of the Bible. His most ambitious project in this vein was The Floating Tower (1971–3, initially called Mishnayot), a cycle of 56 lieder for soloists and choir with piano accompaniment, in which Hajdu offers his sui generis personal interpretation of excerpts from the Mishnah. Among his other compositions on Jewish subjects are Psalms for baritone, boy alto, children's choir and orchestra (1984), the cantata Eternal Life (1984), the opera The Story of Jonah (1987), Job and His Comforters, a biblical and historical oratorio, and Qoheleth, a setting of the book of Ecclesiastes for narrator and cellos (both 1995).

Besides Jewish texts, he was deeply interested in Jewish history. His ‘miniature opera’ for children Ludus paschalis (1970) was based on medieval Jewish and Christian texts and chants. It was commissioned and performed at the Jerusalem Testimonium Festival for Jewish Heritage. This composition touched on controversial issues and created a public stir that positioned Hajdu as a unique voice in Israeli contemporary music. His oratorio Halomot be-Aspamia/Dreams of Spain (1991), commissioned by Bar Ilan University in commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the Jewish expulsion from Spain, is one of his major works in any genre.

However, not all of Hajdu’s output orbited around Jewish themes. He composed many instrumental works in which he followed the romantic and modern European tradition of “pure” music. Examples of this are his piano concertos (1968, 1990) and many chamber works for diverse and original combinations of instruments.

Much of what Hajdu himself considered his major works are groundbreaking pedagogical tools and educational programs. These pedagogical works are dedicated to the teaching of piano and music theory through a creative process that involves the active participation of the student. Among them, one can mention The Milky Way (five volumes of graded exercises for piano to develop compositional and improvisation skills), The Art of Piano-playing, The Book of Challenges, the Concerto for Ten Young Pianists and Orchestra (1977), and Overture in the Form of a Kite (1985). These works attained wide international attention in Europe, especially in his home country Hungary, to which Hajdu assiduously returned after the fall of Communism in 1989.

Overall, Hajdu’s compositions refuse categorization. They reflect his restless character, his constant search for new horizons, and his refusal to abide by any current fashion. By composing music that was basically tonal, he was an outsider during the peak of modernism. In a way, his music prophesied what was going to happen eventually: the disintegration of the avant-garde’s hegemony and a return to music that aims to communicate with the listener through diverse styles. Clearly, his schooling in the modern Hungarian models of Bartók and Kodály, and the 1950s French milieu of Milhaud and Messiaen can be heard in many of his compositions. Yet, uncommitted to any fixed style or genre, each new work by Hajdu contained a stylistic surprise. His humor, irony, communicative nature and most especially his extreme fondness for the little child living inside of him reigned in his works.

Overall, Hajdu’s compositions refuse categorization. They reflect his restless character, his constant search for new horizons, and his refusal to abide by any current fashion. By composing music that was basically tonal, he was an outsider during the peak of modernism. In a way, his music prophesied what was going to happen eventually: the disintegration of the avant-garde’s hegemony and a return to music that aims to communicate with the listener through diverse styles. Clearly, his schooling in the modern Hungarian models of Bartók and Kodály, and the 1950s French milieu of Milhaud and Messiaen can be heard in many of his compositions. Yet, uncommitted to any fixed style or genre, each new work by Hajdu contained a stylistic surprise. His humor, irony, communicative nature and most especially his extreme fondness for the little child living inside of him reigned in his works.

Another of his major pedagogical contributions emanated from his creative teaching at the Israel Arts and Science Academy of the Society for Excellence Through Education. In this experimental boarding school, which recruited a creative cadre of young students from throughout the country, Hajdu had at his disposal a living laboratory for experimenting with new educational ideas and techniques. A number of distinguished young musicians from this school developed outstanding careers and are at the forefront of Israeli art and popular music to this day. Hajdu's devotion to teaching could not be contained by institutions. Many distinguished musicians studied with him privately at his modest home in Jerusalem, a home that was always buzzing with young musicians coming in and out.

In recognition for his achievements in composition and music pedagogy, Hajdu received in 1997 the Israel Prize, the highest distinction bestowed by the State of Israel to its outstanding citizens.

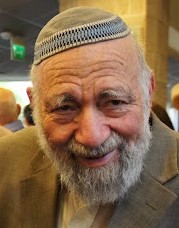

In the last years of his life, Hajdu relentlessly performed, and taught part-time in various institutions such as the Revivim program for Jewish Studies teachers’ diploma at the Hebrew University. He also returned to the JMRC to actively participate in researchers’ seminars as a listener and speaker. Most extraordinary during this period was his work with the Ensemble HaOman Hai, an experimental group which consisted largely of his former students who had become accomplished musicians in their own right. With this ensemble Hajdu produced several programs, one of which was Kulmus Hanefesh, an original presentation based on Hassidic niggunim of the Habad dynasty. This work launched the new CD series of the JMRC, Contemporary Jewish Music, and synthesized in a magnificent way his activities as composer, ethnomusicologist and pedagogue.

Just a few months ago, when his illness had debilitated him beyond recognition, the JMRC launched another of Hajdu’s projects, one of the very last of his rich life as composer, pianist and arranger. Or Haganuz, a collection of lieder for cantor and piano based on traditional pieces of Ashkenazi hazzanut and Yiddish songs, performed by cantor Asher Hainovitz with Hajdu on the piano, was launched to public acclaim last January 7, 2016, in an unforgettable evening at the National Library in Jerusalem.

André Hajdu’s life was paradigmatic of the dramatic upheavals that affected Jews and Judaism in the twentieth century. Multiple migrations by design or by force, evolving attitudes to religious and national Jewish identity and tensions between tradition and modernity in the arts as well as in daily life marked his trajectory. His immense humanistic legacy and inspiration will certainly continue among his many disciples and friends well beyond his awe-inspiring journey on earth.

This obituary draws from Eliyahu Schleifer’s biography of André Hajdu in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2002).