These two autobiographical accounts by Aharon, dating from late 1936 to mid-1943, reverberate in several artist profiles and notices about him written by others and published in the Hebrew and English press in British Palestine. In each encounter with his interlocutors, Azuri provided vivid accounts of different episodes of his life, sometimes contradictory with certain details, at other times filling in details missing from his original biographies discussed above.

Edith Gerson Kiwi, 1937

One of Aharon’s earliest and most important interlocutors beginning during the British Mandate and continuing after Israel’s establishment was the aforementioned German-Jewish ethnomusicologist Edith Gerson Kiwi, who had immigrated to Palestine not much later than Aharon. Kiwi became the assistant of the comparative musicologist Robert Lachmann, also a prominent German-Jewish émigré. As hinted above, Lachman became a pivotal figure for Azuri following his move to Palestine. Azuri first met the music scholar from Berlin at the 1932 Cairo Congress of Arab Music. In 1936, the met each other in Jerusalem, and they were in close communication and often collaborated until Lachmann’s untimely death in 1939. It was a meeting of exiles: one victimized by a repressive anti-Jewish Nazi regime, the other affected by geopolitical instability and perhaps, loss of status within the music community in his native city.

On October 10, 1937 Gerson Kiwi published an article on Ezra Aharon in the Palestine Post as part of a series of essays titled “Pen Portraits of Musicians.” While the basic facts about his life are more or less identical to the information included in Aharon’s autobiographical notes discussed above (and some appear to have literally been copied from them), a few interesting new details emerge from Kiwi’s article. She describes Ezra painstakingly, and even flatteringly, as “vivacious, slender, dynamic, of medium height, alert eyes, and dark… hair.” She also recounts the following evocative anecdote—likely repeating Azuri’s story telling—one which he has not recorded elsewhere:

As a boy, Ezra Aharon lived near the Tigris River, which he grew to love deeply. Whenever he was feeling tired or depressed, we would make a pipe out of the river’s reeds and play it. When he was ten years old his father died and he was free to do as he wishes… Ezra wanted a lute of his own to carry with him wherever he wished but he had no money. Then one day, walking along the river park, he saw a broken musical instrument floating in the water. Taking it out of the river, he saw that it was a discarded lute. He took it, succeeded in repairing it and played it day and night.

This legend about the river as the supplier of musical instruments, and therefore of music itself, aligns with the commonplace conception of the fertile Mesopotamian crescent as the cradle of human civilization. In sharing this intimate story with Gerson Kiwi, Ezra also declared his embodied attachment and deep love, and perhaps also his longing, for the place he grew up in, and where he acquired his musicianship. The tale also supports a hagiographic image of Azuri as a broker of music drawing his inspiration from the local natural landscape in Baghdad. He also recounts becoming liberated from his father’s shackles as a sort of sore parenthesis. By linking his initiation into music to such a profound event as the death of his own father, Aharon dramatizes the painful trauma of his arguably musically-deprived childhood.

Gerson Kiwi’s article also foregrounds Azuri’s relocation to Jerusalem as linked to the death of King Faisal I (September 8, 1933) for whom, as we have seen, Azuri had great affection—as many of his Jewish coreligionists also did. The story of Ezra’s participation in the 1932 Congress in Cairo also foregrounds his receiving the “first prize” in a competition that included all the participant musicians.[9] We also learn from Gerson-Kiwi that Ezra’s connection with Robert Lachmann and his appearances on the “wireless” have lifted up his spirits, hinting that Azuri’s move to Palestine had not been smooth until this point. And Gerson-Kiwi highlights that Aharon established a children’s choir in the Beit Hakerem neighborhood of Jerusalem with “excellent results,” indicating that he had realized that to make a living, he must also diversify his activities to include the educational field. Gerson Kiwi concludes her brief article with Ezra’s vision of creating a new “Jewish music” that will be a “synthesis,” fusing “certain elements of European polyphony with that of the Orient which is homophonic.”

After Lachmann’s death, Gerson Kiwi continued his work. She also remained in contact with Aharon intermittently, recorded him playing, and invited him to provide live musical examples to her lectures, but did not write more about him or his music.

David Tidhar, 1947

David Tidhar, aka “the first Hebrew detective,” was also an Aharon interlocutor during the British Mandate in Palestine. Tidhar, a seasoned private detective, penned the Encyclopedia of the Founders and Builders of Israel—a monumental nineteen-volume work about the “Who's Who” of the Yishuv prior to 1948 and the first twenty-two years of the Israeli state— and he dedicated a substantial entry to Azuri. This entry clearly relied on intimate information supplied by Aharon, and is notable for the space Tidhar dedicated to Azuri in comparison with other musicians of the Yishuv, most especially Arab Jewish artists. This text, published in 1947, is indicative of the notable status that Azuri had achieved in the Yishuv during the Mandate period.

Tidhar’s article reproduces much of the same information included in Azuri’s autobiographies and rearticulated by Gerson Kiwi. Yet, this text includes new details and nuances missing from the previous accounts, likely refashioned by Ezra. For example, the celebrated “first prize” he received at the 1932 Cairo Congress, which comes up in all narratives, is in Tidhar’s account conferred to Azuri “by the King of Egypt,” an occasion of such import that “all the Arab press around the Middle East reported about this important event.” The “two Turkish [music] teachers,” mentioned also by Gerson Kiwi merge into one here, who for the first time is also named: Tanburi Ibrahim Bey.[10] According to Tidhar, Ezra studied with this master for eight years. This means he probably began studying with him in 1919 at the latest, an assumption strengthened by a later account of Azuri in which he claimed that he began dedicating himself fully to the study of music at the age of sixteen (i.e. 1919).

Tidhar’s article also contains details about Azuri’s international career as a recording artist and producer:

“In 1927, he [Ezra] was invited to Berlin by the Baidaphon company (a company for making Oriental records), along with four other Jews and one Arab. They made one hundred and twenty records of Arab songs.[11] That same year he went to Egypt with other singers following the invitation of Odeon, a company producing Oriental records, and recorded about thirty records there. In the years 1930-1931 he was the artistic director of “His Masters Voice” in Baghdad.”

In Tidhar’s account Azuri “had performed many public performances in Iraq and participated in the government orchestra. King Faisal brought him close [to the court] and supported him. He became friends with some of the heads of state.” Once again, Ezra’s proximity to royalty and the elites of Baghdad is emphasized, as well as his indispensability to the local music scene, for Tidhar adds (likely paraphrasing Ezra) that “his leaving of Iraq was a hard blow to Oriental music there, as he [Azuri] did not leave anyone like him there [i.e. anyone who could replace him].” Tidhar also mentions Aharon’s appearances in the Arab programming of the PBS.

B. Ron [Moshe Gorali], 1949

Shortly after the end of the British Mandate in Palestine, another interlocutor provided Azuri with a platform to retell his story. An article in the daily Davar 0f March 4, 1949, signed by B. Ron (pen name of Moshe Bronzaft, later on Hebrewised as Gorali, an Israeli musicologist and educator) offers a favorable, if a bit patronizing, profile of Ezra. The artist provided Gorali with an account of his biography that was very similar, but by no means identical, to the biographies appearing in the accounts of Gerson Kiwi and Tidhar. For example, it is highlighted that Aharon specifies that he studied at the Alliance Israélite Universelle school in Baghdad; that he began dedicating himself entirely to studying music and theory from “many musicians, among them two famous Turkish ones” at the age of sixteen; and it is highlighted that “he appeared with the royal musical ensemble in front of King Faisal at the age of nineteen.” Aharon was nineteen years old in 1922, and we know that he appeared before the King right after the coronation, under the aegis of the British Mandate of Iraq, on August 23, 1921. This means that Azuri was an ascending artist at the center of a society under dramatic political transformations from a vaguely defined Ottoman province inhabited by a plethora of tribes, ethnic denominations and religious minorities, into a nation-state of pan-Arab leanings under the supervision of a European colonial power.

B. Ron’s article, however, is notable above all for being one of the earliest testimonies about Aharon appearing after the establishment of the State of Israel. For the first time we hear something about Azuri’s role among a rapidly evolving Israeli radio audience that includes a fast-growing contingent of Jews from Arab countries, Iraq included. B. Ron reports:

I doubt that many of our singers in the country can claim to have such a large audience of listeners, enthusiastic and faithful, as the singer Ezra Aharon. Out of curiosity and observation, I realized that right at the time Ezra Aharon’s broadcast of begins, the radio sets of thousands of homes of the Oriental communities around the country are turned on and the listeners greatly enjoy the playing and singing of their beloved and admired singer. The admiration of the popular classes bears witness to the quality of the artist.

Interestingly, B. Ron then highlights that Aharon’s artistry is embedded in the high quality of his singing, most particularly as a synagogue cantor and of Oriental Jewish music, rather than on his playing the oud:

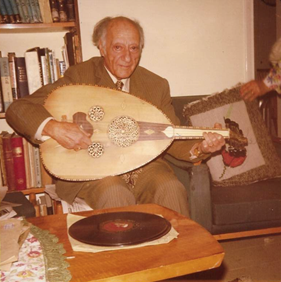

Ezra Aharon is a singer and composer of melodies, instrumentalist and piyyut performer. He commands an extensive knowledge of different branches of Oriental music (Persian, Turkish, Arabic), is an expert in Oriental Jewish music (neginah isra’elit mizrahit) and knows the singing [of Scripture] according to the Masoretic accents. He commands a trove of traditional melodies related to the Jewish holidays and festivals. His voice is pleasant, has a warm sound. He dominates the technique of Oriental singing with all its secrets. Especially beautiful is his ability in ornamentation (silsulim). As common among the best Oriental singers, he accompanies his singing with the plucked instrument, the oud, that he himself had built.

At the end of his report B. Ron emphasizes Ezra’s gift for composition, adding that “the audience in the country (with the exception of the Oriental communities) has not yet come to appreciate the quality and the level of the singer-artist Ezra Aharon. The board of ‘Kol Israel’ has decided wisely to continue in the footsteps of ‘Kol Yerushalayim’ [the Hebrew section of the PBS] by establishing the continuation of his program, as the number of his fans and lovers of his singing is so large.” It is clear from this statement that statehood was not an eventful moment for Ezra’s radio career, as he experienced a smooth transition from the colonial radio station to the post-colonial one. What was changing rapidly was the audience he was addressing. Unappreciated by the “[read: Ashkenazi or European] audience of the country,” B. Ron is pointing to what would become the increasingly marginalized position of Arab culture in the new state and the ethnic minority of “Orientals” (Jews and Palestinians who remained within Israel).

Mishil [Mikhail] Morad, 1950

“Artistic Conversation with Ustad Azuri Aharon,” is an interview published by Mikhail Morad (1906-1986), an Iraqi Jewish poet and acquaintance of Azuri from Baghdad, in the Arabic daily and ruling Mapai (Labor) party’s mouthpiece Alyom on October 6, 1950.[12] The interview, conducted in Azuri’s mother tongue, is characterized by an intimate atmosphere and interdenominational conviviality perhaps reminiscent of the old days in Baghdad: Morad was accompanied by a friend, the Quran reciter Nur Al-Din Rafʿat. He describes the encounter as a “marvelous artistic night” in which they eagerly listened to Azuri’s “eloquent speech, his enchanting music-playing, and his touching voice.”

Azuri is introduced by Morad as “the head of the Eastern Takht of the Israeli [broadcasting Arab] channel,” stressing the main venue through which the intended Arab audience of this interview become acquainted with Azuri. Recapitulating the story of his early path to music as a child during which he attended musical events,[13] and how he overcame his family’s opposition to his “infatuation” with music, Azuri also recounted how he borrowed his first oud from a friend of his brother and how he learned to play it on his own. “Without him noticing, I took it to our house and refused to return it to its owner until my brother bought me a new oud.” He registered at the music conservatory managed by Ustad Ibrahim Tanburi, joining his band before reaching the age of sixteen. After three years with his teacher, he formed his own musical band, with which he traveled to Berlin, where he “recorded hundreds of the cornerstones of Arabic singing and Sharqi Music.” Azuri’s participation in the 1932 Cairo Congress is stressed in this interview as well, casting the event as a “competition of ancient singing[14] and the performance of maqamat, and musical modes, and musical theory. We [the Iraqi delegation] won the first prize in that competition among the Arab countries.”

Unlike Azuri’s previous coverage by Jewish journalists and interlocutors, the interview with Morad mentions his most famous Arab compositions, such as Ḥilm al-Musiqa,[15] “which was praised by the Palestine Post, and many were captivated by it.” Assuming a certain continuity with the local Arab audience from his years at the PBS, Azuri also stressed his four years’ tenure at the Arab section of the mandatory station in which he “made numerous artistic innovations, like establishing the Western musical band, led by [Palestinian musician] Mister [Yousef] Batrouni” and recording Arab songs and pieces like Ṭalaʿ al-Badr ʿAlēna[16] and Yom Baʿṯ al-Musṭafa,[17] “as well as music for the Opera ʿAntara,[18] which was broadcast among others.”

At this point Morad’s conversation with Azuri moves from the biographical to the more programmatic narrative. Azuri praises “the fusion of ancient and new melodies, using Eastern and Western instruments” as a path to “advance music towards its goal: progressing to new styles of expression and performance.” This modernist drive does not imply abandoning the past, adding that “ancient Sharqi melodies… must be considered cultural heritage: they should be preserved and safeguarded in (our) collective memory and history.” Azuri is also concerned with music education in the new country, praising the government for “trying to promote the study of music…[as] an essential step for the development of musical taste and the exploration of artistic talent.”

Morad’s own agency as an involved Arab intellectual is also sensed in this interview. Recalling that the Israeli broadcasting station does not broadcast in its Arabic-language programs any hymns[19] or music to accompany the news, Morad asked Azuri to intervene and change this state of affairs. The interview ends with a question about Azuri’s future artistic plans, an issue rarely mentioned in his encounters with Jewish interlocutors. “If I’ll be able to, I would like to establish a music academy and form an orchestra, through which I’ll be able to widen performance styles. I am certain that with the help of the department manager of the Arab Israeli broadcasting station, we will soon accomplish this goal. The field will open for broad innovations and new compositional work, to the satisfaction of the audience.” Azuri adds that the head of the Arabic department of the Israeli radio station “works days and nights on the programs that he is responsible for – he makes endless efforts to serve the Arab society in Israel.” Some of these plans were indeed realized with the establishment of the Arab music orchestra of the Israeli radio during the 1950s and 1960s.

The intimacy of Azuri’s encounter with Morad and Nur Al-Din Rafʿat is notable throughout this text. Azuri honored his guests by playing some of his pieces with joy, unexpectedly adding as an ending note: “I do not smoke, nor do I ever drink wine; I get intoxicated by the crowd’s cheers while they become harmonious with the taste of my melodies.” He continued by saying that “smoking and drinking are harmful to the nerves of the instrumentalist and the throat of the muṭrib;[20] and you wouldn’t consider me to be more than thirty-seven years old, when in fact I have already passed the age of fifty.” As we know that Azuri was born in 1903, Ezra actually was only forty-seven years old at the time of this interview.

A. Ben Haim, 1960/1

Another interview, titled “King of the Oud,” appeared in the journal Shevet ve-‘am (vol. 5 [1960/1]: 102-105)— a publication of the Israeli branch of the World Sephardic Federation. The writer, A. Ben Haim, interviewed Azuri at his home in Jerusalem in the working-class Kiryat HaYovel neighborhood. His report provides highly laudatory and sympathetic prose for his interviewee, describing Ezra’s “humbleness, soft voice, glowing innocent eyes of goodness, like the sorrowful sounds of maqam Saba”. The style of this conversation opens ample space for Ezra to express himself. There is not only a sense of intimacy, but almost an ethnographic gaze, highlighted in Ben Haim’s detailed description of Ezra’s living: “on a cabinet, family pictures are displayed, diverse types of musical instruments are hung here and there, poetry books by Bialik, Tchernichovsky, Yaacov Cohen [are] on the cabinet. In the middle of the Eastern wall hangs an amulet made of parchment with verses from the ‘Holy Zohar’ [the primary medieval text of Kabbalah] and in front of it is a large picture of Schubert [probably Beethoven] seated on a bench on the banks of a river while devising melodies.”

In this interview Azuri, now an Israeli state employee, provides details about his life experience that do not appear in any other source. Some of these details are minimal for the story’s trajectory, but are still meaningful, as they shed light on Azuri’s changing relationship to his past at a more advanced age (around fifty-six when Ben Haim met him). One example is the first-time reference to his father by his first Arabic name, Bassam, and his occupation, an “international trader.” This is a more intimate and factual reference to his father in comparison to the resentful descriptions of him as staunchly opposed (to the point of physical violence) to Azuri’s musical career appearing in earlier sources. Other details provide a window how Azuri viewed his life in retrospective. According to this new testimony, his interest in music began at the age of five and by the age of eight he was an accomplished player, largely through attending events in order to listen to musicians. This information contrasts with the earlier versions about the beginnings of his career at the age of ten, when the death of his father “liberated” him to fully engage with music. We also learn that he studied music with the Turkish teacher [Tanburi] Ibrahim Bey in Istanbul rather than in Baghdad, a meaningful detail that thus far no other document in Azuri’s archive corroborates.

In addition, Ezra highlights his indebtedness to David Avisar, his staunch and most valued supporter:

And all he [Ezra] makes [in terms of musical creativity], he made under the devoted guidance of his mentor [morehu, lit. “his teacher”], David Avisar. He [Avisar] opened his eyes to the spirit [ruah, in Hebrew also means “wind”] of poetry that arises [menashevet, lit. “blows”] from the pages of the Bible, [from] medieval [Hebrew] poetry, and from Tziyon ha-lo tish’ali li-shlom asyraikh [a famous poem by Yehudah Halevy that Ezra composed in the mid-1930s], and [from] the songs of Israel Najara and Y[ehuda] L[eib] G[ordon] up to Rachel and Elisheva. All these [musical] works are written down in notebooks awaiting for their redeemers.”[1]

Finally, Ben Haim also stressed that at the time of the interview (1960) Azuri did not trust musical instruments made by others, only those he makes by himself.

After recapitulating, once again, how warmly Ezra had been received in the circles of the newly-established Iraqi court of the 1920s, a story framed in the style of a folk tale is recounted:

“The said King [Faisal] told him: ‘My son, you made me happy, happier as I have never been during all my life,’ and the ceremonial head of the court added and said: ‘You will illuminate with music the image of Iraq.’ Once Ezra Aharon was offered a vase full of ancient gold dinars from the days of Harun al-Rashid, and on the dinars the explicit name [of God] was engraved in Kufic (Ancient) Arabic, each dinar had a gold chain. They told Ezra: ‘take from the vase as many as you crave. May God rejoice your heart, as you rejoice our hearts.’

This tale recalls two Jewish brothers from the Abbasid Era, who were gifted musicians [heiytivu naggen, after Psalms 33:3], Ibrāhīm and Isḥāq al-Mawṣilī,[2] as well as al-Zalzal [the Persian musician Manṣūr Zalzal al-Ḍārib, teacher of Isḥāq al-Mawṣilī], who used to say: ‘may God extend the life of our King Harun al-Rashid. And we filled our homes with gold and silver.’ However, Ezra took from the vase only one dinar and he showed it to us.”

This fantastic tale, in the style of the One Thousand and One Nights, elevates Aharon to the status of the greatest musicians of the Arab court at the peak of its splendor during the Abbasid era. The leading musicians, who were actually all Muslim, have been Judaized, perhaps to equalize Ezra’s position with them or to indicate the Jewish origins of Arab music. However, Ezra is critical of his predecessors’ greediness, casting himself retrospectively as a modest servant who does not abuse the generosity of his royal benefactors.

This tale however is not the only one peppering Ben Haim’s report from which Azuri emerges as a skilled folk tale teller, in particular of Arab stories about the mythology of music going back to the glorious days of the Abbasid Caliphate. For example, he entertains Ben Haim with a relatively long folk narrative about the invention of the oud by Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (870-951).[23] At a certain moment in the conversation, Azuri grabs the oud and plays sounds of maqam Saba that are full of “yearning and longing,” at which point he elaborates on the cosmology of music according to the “ancients and astrologists” who believed in the relation “between music, the stars and the zodiac signs.” “Each sound has its moment and its hour” adds Ezra, linking medieval Arab concepts about the powers of music to biblical settings:

The psalm of the day (mizmor shel yom) that the Levites used to sing in the Temple undoubtedly hint at this idea. The seven scales of music mirror the seven planets, the seven days of the week and the seven colors of the rainbow. Rast is first and foremost among the scales and the rest of the scales derive from it. Yes, yes, my dear friend, Saba is the saddest among the sounds as much as joy is the household of Hijaz…

Interestingly Azuri also tells Ben Haim stories based on the ethnographic expeditions among the Bedouins in southern Israel that are also documented in pictures kept in his archive. He elaborates on the Bedouin fiddle called rebab, which is “made of a wooden board with one string, that all [it plays] is half a scale and produces four or five tones; and the Bedouin expresses with this [simple] instrument his longing for life in the desert and in nature, songs of jealousy and love, war and peace, a song of water and a song of the harvest.” This unconcealed admiration for the “primitive” music of the Bedouin is Ezra’s own Orientalist take, as a contemporary Arab urban musician, on the modern loss of music’s innocence, of its simplicity and closeness to pristine nature.

Finally, from the distance of almost three decades after his relocation, he recounts that the sojourn to Jerusalem after the Cairo Congress of 1932 “provided him with the greatest gift of his life, the love for his ancient land [of Israel].” Then he adds that:

When the Baghdadis learned that Ezra Aharon wanted to leave them, they were hurt that this treasure [kli yaqar, lit. precious instrument or, by extension, professional] is asking to move to another land, ‘a land in which disturbances abound, and [in spite of this] he abandons all the goodness the land of Babel has to offer’ [notice the quotations in the original, i.e. this is not Ben Haim’s paraphrase of Ezra’s wording but a direct quotation]. More than once, they have threatened him and tried to take his life, unless [so that] he abandons this idea. Ezra stood by his decision and refused to abide by this request, he immigrated [‘alah] to the Land [of Israel] and he suffered the bitter agony of absorption. He did not command the Hebrew language, his music [neginato] did not attract attention, he was hungry for bread, he sold his expensive carpets and jewelry, but he did not cast any doubts about the land and its inhabitants, even attempting to bring his parents [from Baghdad][24] to the country, while a pleasant welcoming accompanied him wherever he went.

Recounted in 1960, these stories reflect Azuri’s internalization of the Israeli Zionist ethos so prominent in those days. The Jewish longing for the ancient homeland and resistance to the temptations of diasporic life (wealth, fame) are prominent in this narrative, hence Ezra’s determined decision “to ascend” which, however, came at a heavy price. Immigration entailed a big loss, financial impoverishment and suffering. Referencing the difficulties involved in adapting to an extraneous society, are foregrounded during a period of incipient revolt of Jews from Arab countries against the discriminating absorption policies of the overwhelmingly Ashkenazi establishment. Yet, in spite of all the tribulations, Ezra presents himself as one that remains a faithful patriot of his adopted country, which, contrary to the difficulties involved in uprooting, has welcomed him with sympathy.

Ezra also conveys to Ben Haim the deep paradox embedded in his new life. On the one hand, he believes in the power of his art because “[Oriental] music is one of the treasures of culture that will bring the Orient closer to us,” And he presents himself as the composer of the soundtrack of the country’s important occasions: the inaugurations of Chief Sephardic Rabbi Ben Zion Uziel and the President of Israel, Itzhak Ben Zvi; David’s Lament for Jonathan on the day the major of Tel Aviv, Meir Dizengoff, died, and the national poet Bialik’s “Behind the Gate” [Meahorei Hasha’ar] during the “White Paper” period (1939, when the British Mandate dramatically curtailed Jewish immigration to Palestine). On the other hand, he notes that his music is dismissed, and he asks “for whom do I labor?” At this point, toward the end of his article, Ben Haim adds that “an oppressing feeling of loneliness” surrounds Azuri.

Conclusion

The (auto-)biographical narratives—those penned by Azuri/Ezra himself, exposing his own perceptions—or delivered (with one exception) through the agency of a mostly admiring audience of Jewish interlocutors, cover Azuri’s early life and the first two and a half decades he spent in British Mandate Palestine/Israel (1934-1960). The dynamic nature of autobiography is patent in these texts. Ezra’s narrative evolves along time, adding and subtracting details, emphasizing issues that are pertinent at certain stages of his career while abandoning others that had become obsolete. For example, the nuances in his telling of the events that precipitated his leaving Baghdad shift along time, aligning more and more with the Zionist ethos that he adopts as the years go by. At the same time, the feeling of loss of the status, wealth, honor, and recognition he enjoyed in Baghdad also seems to grow over time. His immersion in the ethos of the past glories of the medieval Arab Empire and its glorious capital, Baghdad, in his conversation with Ben Haim, as well as his elaboration on chapters related to its music history, cosmology and personalities, appear as the longing for a paradise lost to which he looks back from a less pleasant present.

There is of course an element of escapism in this discourse but also an expression of the contrasting memories constantly reshaping Azuri’s fluid consciousness. These contrasts tangibly (and also symbolically) cohabit in the living room if his Kyriat HaYovel apartment, where traces of Jewish folk religion and magic (amulet with verses from the Zohar) coexist with secular Hebrew nationalism (books of modern Hebrew poetry rather than Jewish religious texts), Oriental music instruments hanging on the walls and a picture of an icon of the classical Western music tradition (Schubert, or perhaps Beethoven).

The latter parts of his life, a period of artistic eclipse and retreat from public eye, are addressed by Azuri in his encounters with a new generation of scholars who met him under very different circumstances, when he was old and long after he retired from his post at Kol Israel in 1967. Interviews with Aharon carried out by Esther Warkov (in collaboration with Philip Bohlman), and by Amnon Shiloah in 1981 add another source of primary information about the Iraqi musician. These scholars met Aharon in his twilight years, when he was a forgotten celebrity who looked back at his glamorous past life through the lenses of a gloomy present. These interviews differ from Azuri/Ezra’s direct reflections discussed in this document and are analyzed by us in other publications.