Rav Riccardo Shmuel Di Segni (2020)

‘Le-El ‘Olam’ by Mordecai Dato: In search of a melody for an ancient Italian Hebrew poem

Not much is known of the life of Rabbi Mordecai ben Yehudah Dato (1525? – 1593-1601?).[1] We do know that he sojourned in Safed in the Upper Galilee in 1560, where he studied with R. Moshe Cordovero,[2] and that in his native country he settled in San Felice sul Panaro, a very small town located between Modena and Ferrara where he maintained a rather secluded life. Almost all of his works remained in manuscripts (except for a few songs, as will be shown below). Many of Dato's works are poems, and our Song of the Month delves into one of them, ‘Le-El ‘Olam’.

A number of Dato’s poems show his engagement with the increasing popularity among his compatriots of a new ritual eventually called Qabbalat Shabbat. These rituals emerged around the mid-sixteenth century from the circles of Jewish mystics of Safed and spready rapidly throughout the Jewish world, especially to Italy. One key figure in these Safedian circles was R. Shlomo Alkabetz (1505-1584), whose poem ‘Lekhah dodi’ became the center piece of this new ritual up to this day.[3]

The normative order of Qabbalat Shabbat as practiced today, however, was not the only option available during Rabbi Dato’s time and even afterwards. An alternative order incorporating additional kabbalistic texts and Psalms to the ones in use today circulated in several seventeenth- and eighteenth-century manuscripts.[4] Significantly, this alternative Qabbalat Shabbat incorporates two poems by Mordecai Dato, the aforementioned ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ and ‘Bo’i Kallah’ in addition to ‘Lekhah Dodi.’ Even more important for the main musical argument of this Song of the Month (see below), the majority of the manuscripts containing the Qabbalat Shabbat with Dato’s poems originate in the city of Ancona.

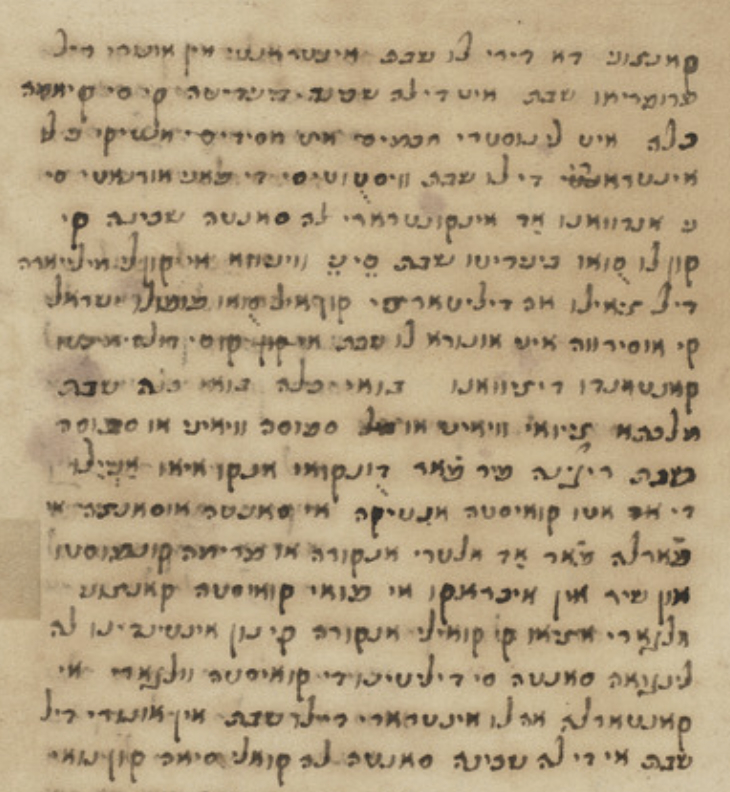

Dato also composed a long poem connected to the idea of Qabbalat Shabbat, ‘Ora vien o bella sposa’ (Come now, o beautiful bride), in Judeo-Italian – in an Italian volgare, that is, written in Hebrew characters and with many Hebrew loan words. The poem, which clearly dialogues with ‘Lekhah dodi’, is found in a manuscript dated from the end of the sixteenth or beginning of the seventeenth century, located today in the special manuscripts’ collection at the library of the University of Leeds.[5] First studied by Cecil Roth who originally owned this manuscript,[6] it is a fascinating text. Though lacking the powerful kabbalistic imagery of ‘Lekhah dodi’ it offers a very long exposition (230 five-verse stanzas) of salient moments in Jewish history alongside some description of Jewish life in a Renaissance Italian household. In the introduction to the poem, Dato writes:

קנזוני דא דירי לו שבת אינטראנטי אין אונורי דיל פרופריאו שבת איט דילה שכינה בינידיטה קי סי קיאמה כלה איט לי נוסטרי חכמים איט חסידים אנטיקי ני לו אינטרארי די לו שבת וויסטוטיסי די פאני אורנאטי סי ני אנדוואנו אד אינקונטרארי לה סאנטה שכינה

Song to be said at the coming of Shabbat, in honor of Shabbat itself and of the blessed Shekhinah that is called Kallah [Bride], and our sages and hasidim of old on the arriving of Shabbat, dressed in decorated robes, used to go and greet the holy Shekhinah….

Dato goes on to mention in this same introduction the last stanza of ‘Lekhah dodi’ (“they used to sweetly sing בואי כלה בואי כלה שבת מלכתא”); and explains that he too, in order to introduce this “ancient time-hallowed custom” to his Italian coreligionists, has written “another song in Hebrew” and now “this one in volgare” so that those who yet do not speak the holy tongue can sing the praises of the Sabbath as a bride. Coincidentally, the entire poem ‘Lekhah dodi’ is also included in the same manuscripts from Leeds (fol. 31b) with interesting variants as already noticed by Cecil Roth.[7]

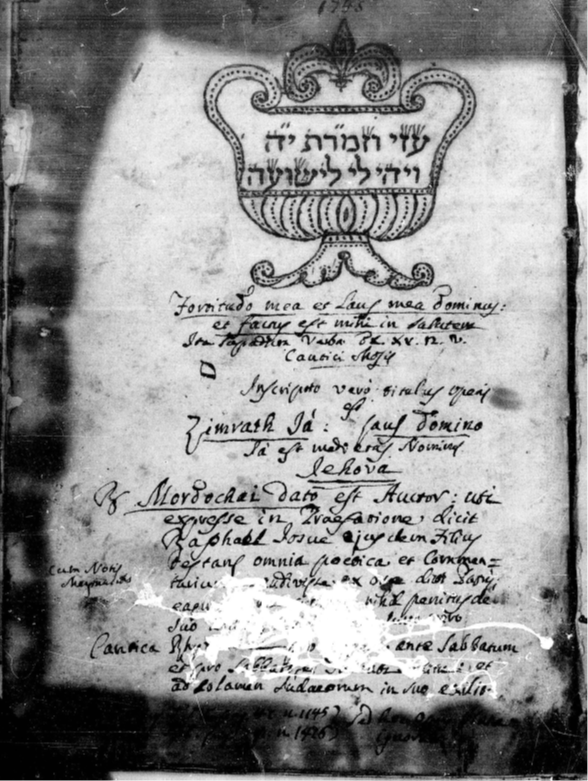

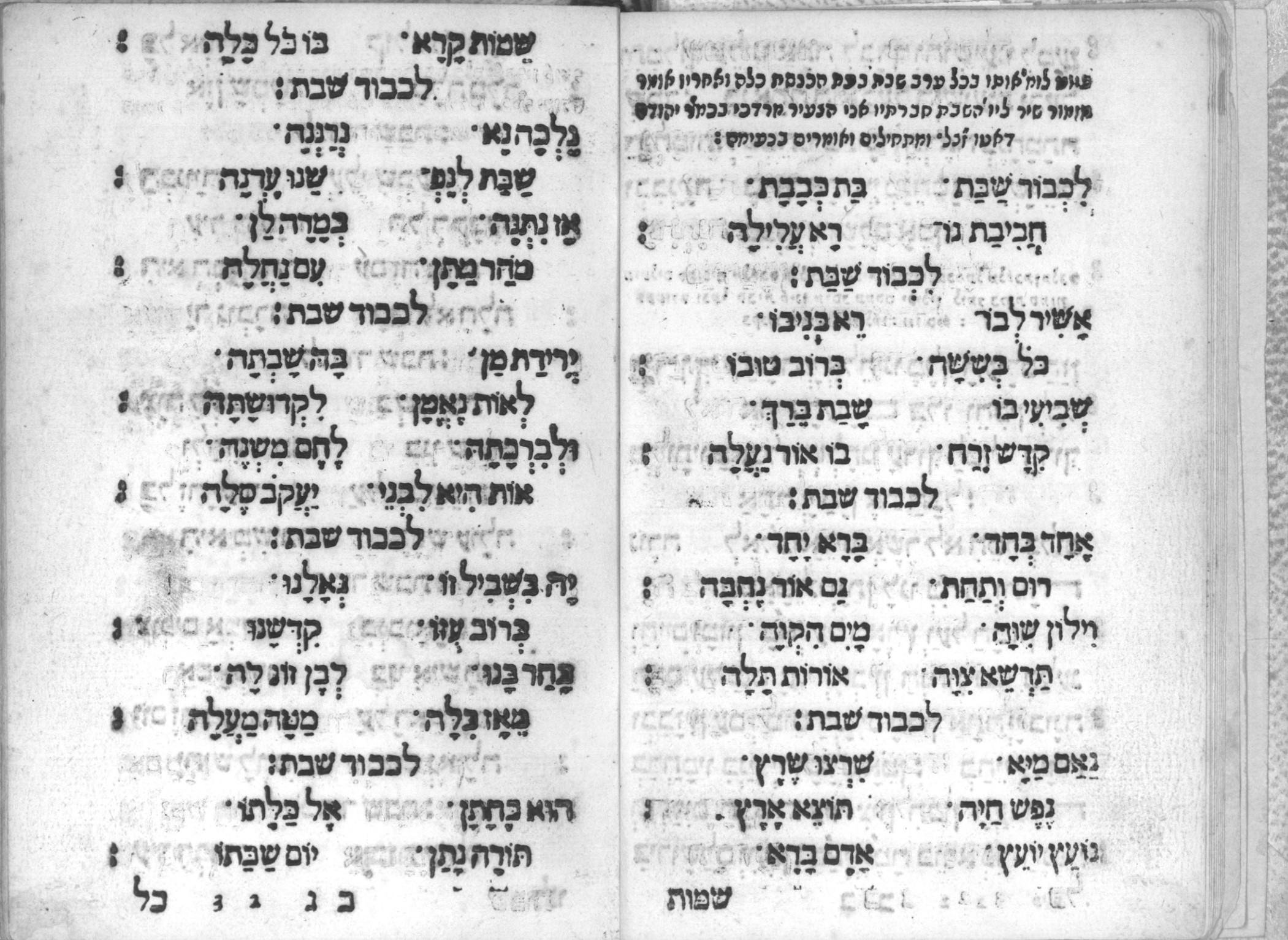

To which “other Hebrew song” Dato is referring in this passage we do not know exactly. A good candidate may be his poem ‘Likhvod shabbat bat kevavat’ that appears for example in the Siddur Mi-brakhah Ke-minhag q”q Italiani (Venice, 1618).[8] In the Italian siddur Dato's Hebrew poem is intended to be sung before ‘Mizmor shir leyom hashabbat’, i.e. as an introduction to the Qabbalat Shabbat ritual and not as a substitute to ‘Lekhah dodi.’ As it turns out, ‘Likhvod shabbat bat kevavat’ consists of two sections, the second of which is ‘Bo’i Kallah’ mentioned above as part of the expanded kabbalistic Qabbalat Shabbat. The entire poem with both sections included back-to-back appear in a manuscript titled Zimrat Yah (Rome, Casanatense, Ms 3097) compiled by Dato’s son, Refael Yehoshua and containing his fathers’ poetry with ample commentaries.

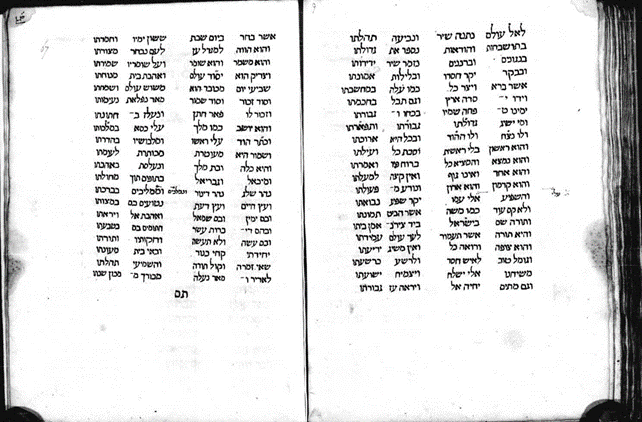

Another composition of his that R. Dato may be referring to is ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ that was included in his collection of poems Shemen ‘Areb that remained unpublished in a manuscript of the British Library and appeared in print only in 1910.[9]

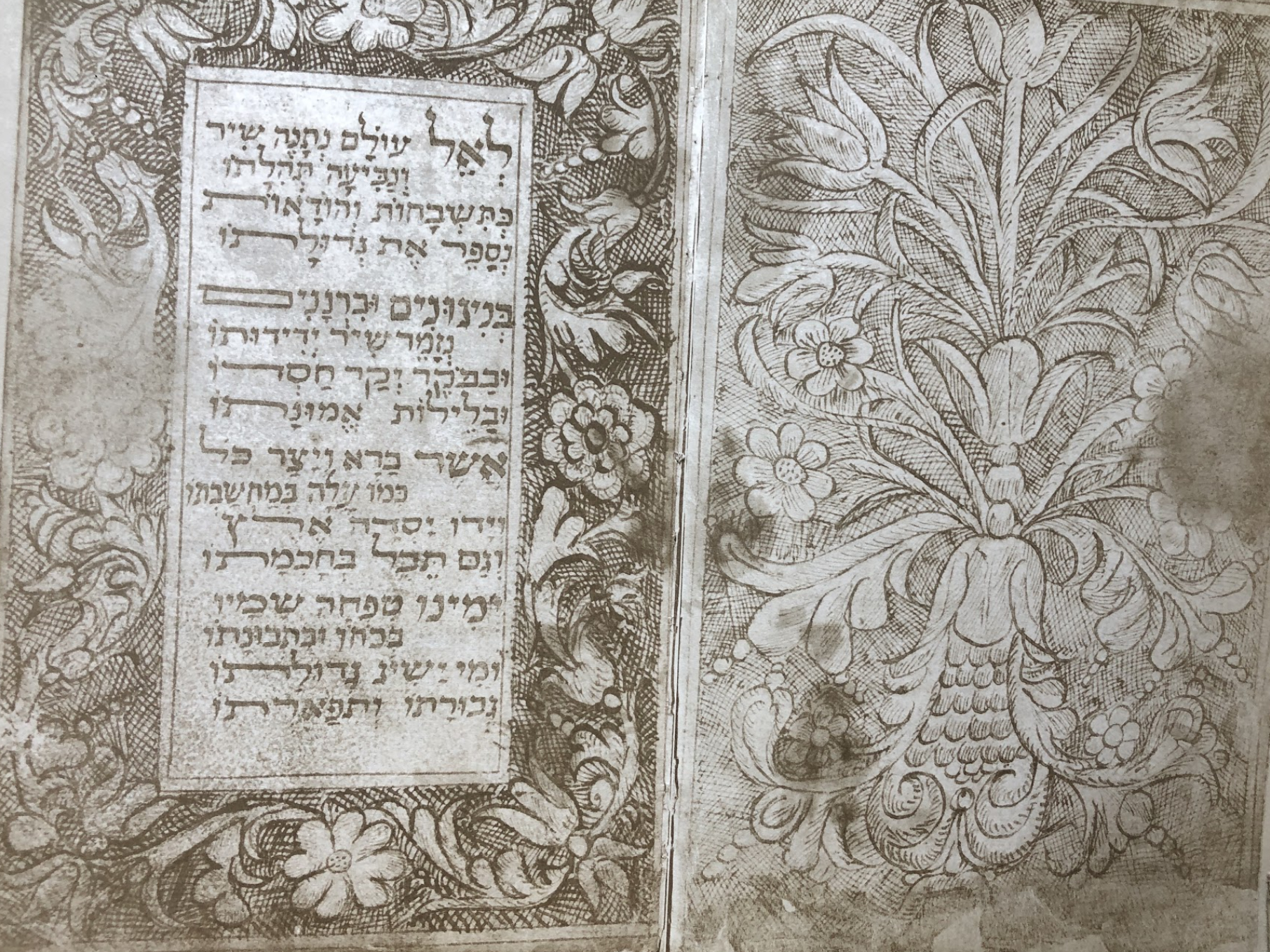

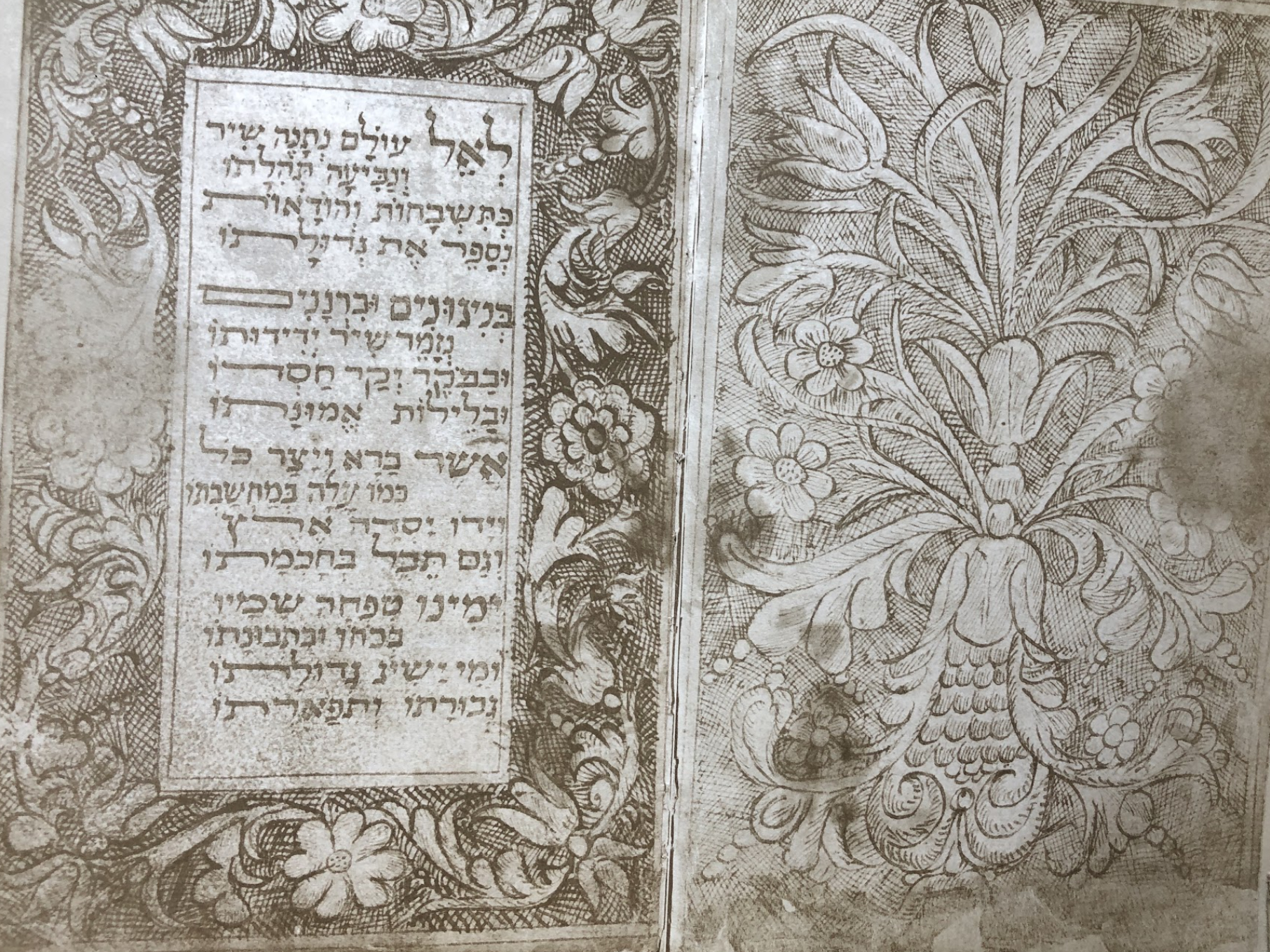

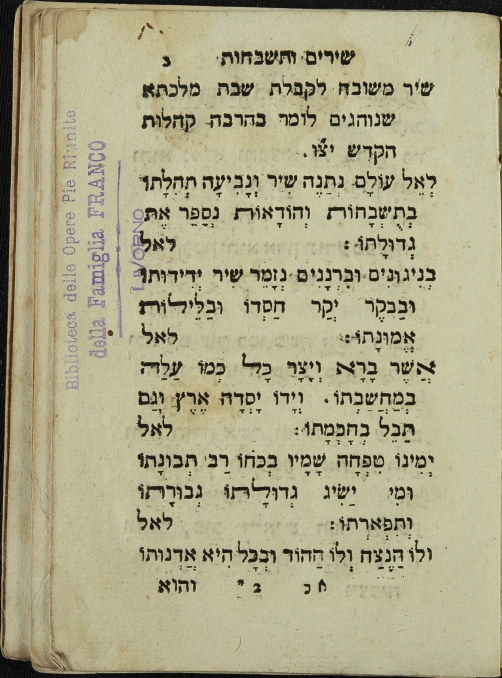

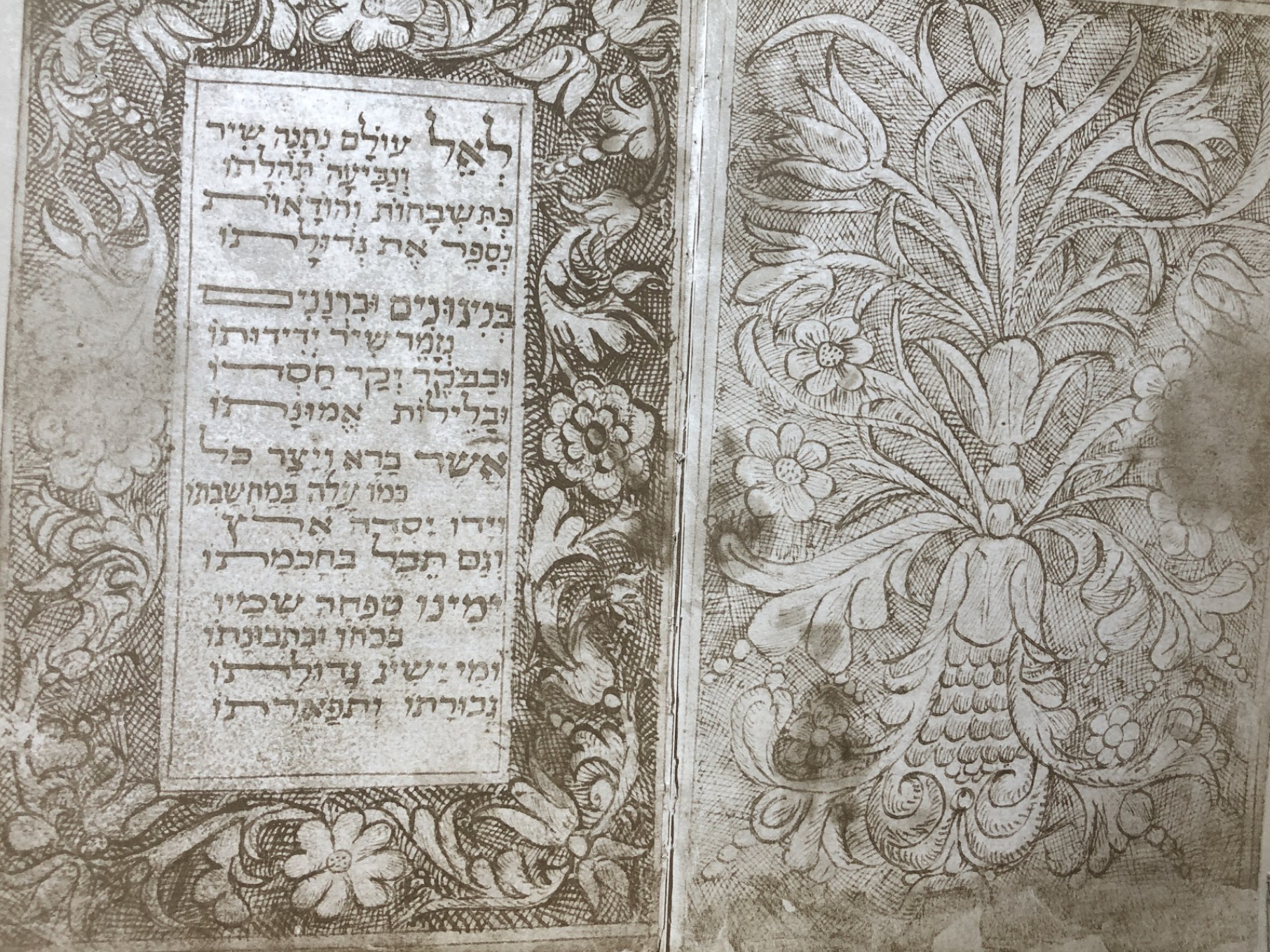

However, ‘Le-El ‘Olam’, an interesting poem incorporating in it the Thirteen Attributes in a manner reminiscent of the widespread poem ‘Yigdal Elohim Hay’, had already appeared in print in Seder shirim vetushbahot published by Itzhak de Moshe de Paz in Florence in 1755.[10] In this collection the poem is introduced as “the much praised song to welcome the Sabbath Queen that is customary to say [i.e. sung] in many Holy Congregations”. This publication is basically an early prototype of the modern bentsher, a pocket-size booklet with the order of the Sabbath rituals at home, including songs to be performed before, during and after the festive meal. Here is the first page of the poem as published in Seder shirim vetushbahot.

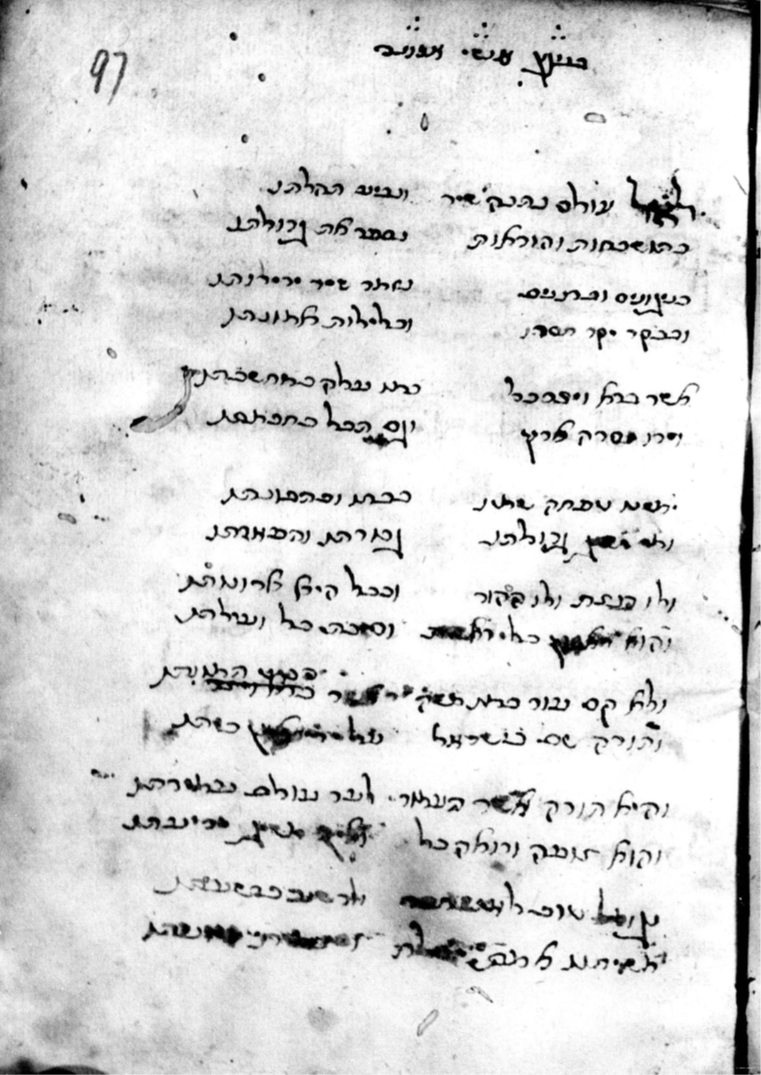

The oldest manuscript version of ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ is on Ms. 10471 of the British Library dated in 1581, i.e. while the poet was still alive. This version, with corrections apparently by Dato himself, includes a musical reference in its title, “Benigun anshei emunah’ i.e. an indication that the song is to be performed to the tune of a song whose first words are ‘Anshei Emunah,’ most probably the widespread ancient seliḥah ‘Anshei Emunah ‘Avadu Ba’im Be-koaḥ Ma’aseihem’.

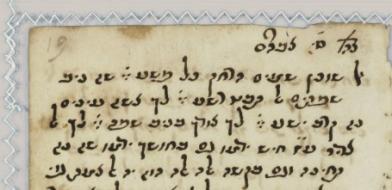

A very interesting source in which ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ appears is Sefer ha-maftir shel Urbino, a manuscript donated in 1956 to the then recently inaugurated Italian synagogue in Hillel St. in Jerusalem, and later on published in a bilingual – Italian and Hebrew – annotated version in 1964.[11] Compiled in 1710, the manuscript is an ornate little book written in the central Italian town of Urbino, in honor of a young man’s first reading of an haftarah, even before his formal initiation as a bar mitzvah. The author – or the person who commissioned – the manuscript writes in the colophon in Hebrew:

When you see this work, do not be surprised; this is the use in Urbino, that he who reads the Haftarah also sings in the synagogue the hymn ‘Le-El ‘olam’ and ‘Bame madliqin’ and he opens the “Alfa-beta” [i.e. the reading od Psalm 119, an alphabetical acrostic] at the end of Shabbat Minhah [Sabbath afternoon prayer], and [also reads] a chapter [of Pirqe avot, the Mishnaic Tractate ‘Ethics of the Fathers’] when it is [traditionally read, a chapter on each Sabbath] between Pesah [Passover] and Shavuot, and everyone has something like this [book] and so I made one for Yosef, son of my son Yitzhaq, may his Rock [God] protect him.

As ‘Le-El ‘olam’ is the first piece to be sung by the young person in question, it appears in a flowery script at the beginning of the book.

This source suggests that Dato’s ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ was performed, as we have seen in other manuscripts, as an introduction to Qabbalat Shabbat in various Italian synagogues until at least the second half of the eighteenth century as attested by its publication in 1755.[12]

Two centuries later, however, the performance of this poem all but disappeared from the Italian Jewish musical memory. Yet, we find some vague traces of its persistence in small communities in the center of Italy. Rabbi Elio Toaff, born in Livorno, who was Chief Rabbi in Ancona from 1941 to 1943 and later in his life the Chief Rabbi in Rome, and who also acted as informant of the distinguished ethnomusicologist Leo Levi, attests to the modern presence of ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ in the Ancona ritual. Toaff published the text of Dato’s song together with an Italian translation in a small, numbered edition in 1950 which was then reprinted in the aforementioned bilingual publication of Sefer ha-Maftir (Jerusalem, 1964).

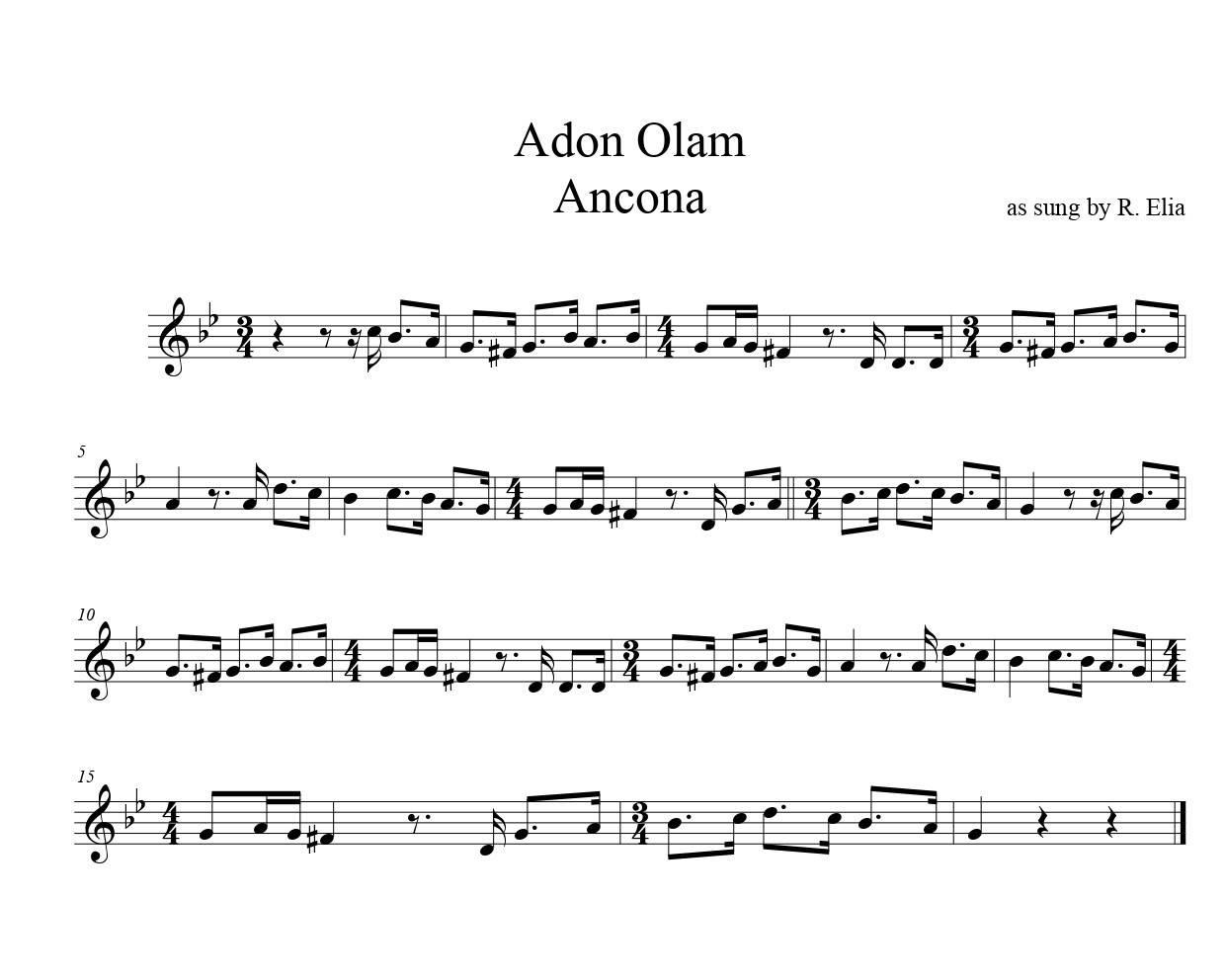

Did any traditional melody for ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ survive in oral tradition? Unfortunately, Elio Toaff did not record this song. Yet, if we look through the Ancona repertoire recorded by Leo Levi, we come across a very promising candidate; n. 397 in the catalogue published by Levi (in: Centro Nazionale Studi di Musica Popolare, Roma: Catalogo Sommario delle Registrazioni 1948-1962, Roma, 1963) reads: “Introduzione al ‘Lecha Dodi’ per ogni venerdì sera; inno e motivo tradizionale liturgico proprio del rito anconetano-italiano. Ancona (ma a Milano). Voce maschile. Intonazione religiosa.” (Introduction to “Lekhah Dodi” for every Friday night; hymn and traditional liturgical tune typical of the Italian-Ancona ritual. Ancona (but in Milan). Male voice. Religious intonation). The recording was made in February 1954 in Milan. The informant, Raoul Elia, had moved to Milan after the war and worked for the local Jewish Community as it was gradually rebuilding itself. Here is a link to the recording on the Online Thesaurus of Italian Jewish Music, and you can listen to it here:

R. Elia, Ancona (1954). Item in Thesaurus of Jewish-Italian Liturgical Music

The song recorded by Elia is not ‘Le-El ‘Olam’, but the famous poem ‘Adon ‘Olam,’ among the most widespread piyyutim of the Jewish liturgy that is performed either at the beginning or the end of morning services, depending on local tradition. How can one explain then the very unusual liturgical location of ‘Adon ‘Olam’ as introduction to Qabbalat Shabbat as described by Levi in his annotation to this recording? Moreover, why would Levi state in that same annotation that not only the tune but also the hymn itself are typical of Ancona, as attested by the manuscript evidence mentioned above, while we know that ‘Adon ‘Olam’ is found in every Jewish community around the globe?

Another significant piece of information in Levi’s annotation to Elia’s recording that has often been overlooked is the “place of recording”, i.e. Milan rather than Ancona. Is it then possible that Raoul Elia did not have the text of ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ at hand and decided to record the unique traditional melody of this poem, which is as we have seen in the manuscript evidence a distinctive trait of the Ancona ritual, with the familiar lyrics of ‘Adon ‘Olam’, a text he knew by heart? After all, ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ and ‘Adon ‘Olam’ and structurally and metrically identical. This is not a farfetched hypothesis, because Dato’s poem that, as we have seen appeared in many Italian siddurim and mahzorim until the eighteenth century, has totally disappeared from the modern Jewish prayer books used in Italy.

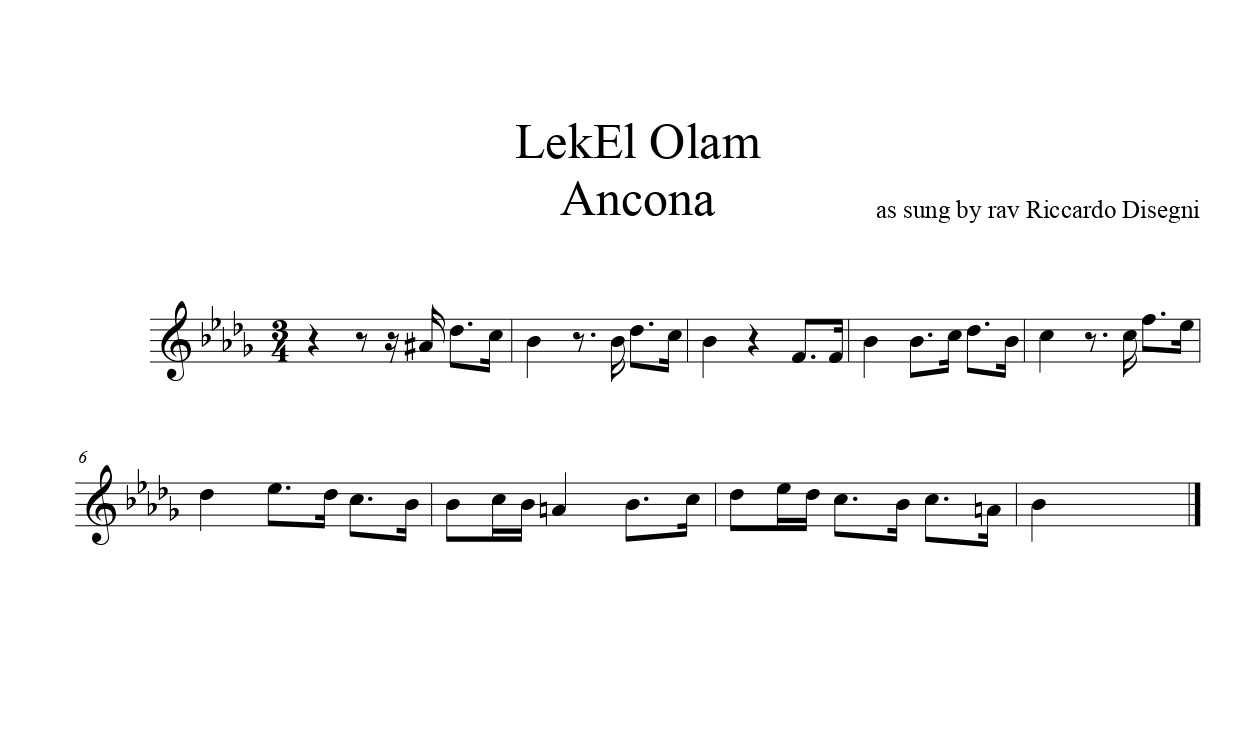

Naturally, this is only a hypothesis. In recent years we inquired among Italian cantors if anyone had a memory of ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ as sung in Ancona or better a recorded trace of it. Very recently, a new significant testimony has surfaced. Rav Riccardo Shmuel Di Segni, the present-day Chief Rabbi of Rome, informed us that he could remember a melody for ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ as it was taught to him by the late Rav Giuseppe Laras, who earlier in his career had been Chief Rabbi of Ancona from 1959 to 1968 before becoming one of Italy’s most well-known and respected Jewish intellectual figures of the second half of the twentieth century. Rav Di Segni recorded for us the melody he remembered, and you can listen to it here:

Rav Riccardo Shmuel Di Segni (2020). Item in Thesaurus of Jewish-Italian Liturgical Music

A comparison of the melodies recorded by Rav Di Segni’s and by Raoul Elia (although with a different piyyut) led us to conclude that this is indeed the Ancona melody for ‘Le-El ‘Olam’, the only traditional tune to have reached us for this once very well-known poem for the Sabbath by R. Mordecai Dato.

As a parting salute to Mordechai Dato and his poetry, we invite you to listen to a contemporary rendition of ‘Le-El Olam’ with the Ancona melody; and to the Ensemble Lucidarium’s version of Dato’s poem for the Sabbath in Italian ‘Ora Vien, o Bella Sposa’ (for which no traditional melody is likely to surface soon), set to a melody by one of R. Dato’s most illustrious contemporary musicians, the lutenist and composer Cosimo Bottegari (1554-1620).

Le-El 'Olam from Ancona, Radicanto at Erev-Laila festiva, Trieste 2021. Item in Thesaurus of Jewish-Italian Liturgical Music.

I would like to thank Prof. Edwin Seroussi for his valuable suggestions and additions that contributed to the enhancing of this article.

video description

Ora Vien o Bella Sposa (poem by Mordechai Dato) - Ensemble Lucidarium, Gorizia 2020

Footnotes

[1] For Dato’s biography see, Giulio Busi, La Istoria de Purim io ve Racconto… (introduction), Bologna, Luisè Editore, 1987; Yaacov Jacobson, Along the Paths of Exile and Redemption: Doctrine of Redemption of Rabbi Mordecai Dato, Jerusalem, Mossad Bialik, 1996. (In Hebrew)

[2] Isaiah Tishby, דמותו של רבי משה קורדובירו בחבור של ר' מרדכי דאטו, בתוך: ספונות, ספר ז (תשכ"ג), ע' קכא-קסו (The Persona of Rabbi Moshe Cordovero in a Work by R. Mordecai Dato).

[3] See the indispensable study of this poem by Reuven Kimelman, The Mystical Meaning of Lekhah Dodi and Kabbalat Shabbat. Jerusalem, Magnes, 2003. (In Hebrew)

[4] Ezra Chwat, An Alternative Qabbalat Shabbat, https://imhm.blogspot.com/2007/12/ezra-chwat-alternative-qabbalat-shabbat.html

[5] Leeds University Library, Ms. 51;https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections-explore/115724

[6] Cecil Roth, Un Hymne sabbatique du XVIe siècle en judéo-italien, Revue des études juives 80 (1925), no. 159, pp. 60-80; no. 160, pp. 182-206; 81, (1926), pp. 55-78.

[7] On these variants and on the diverse kabbalistic practices related to Qabbalat Shabbat and Mordecai Dato’s poems, see Moshe Hallamish, Kabbalistic Customs of Shabbat. Jerusalem, Orhot, 2006, esp. pp. 224-237. (In Hebrew)

[9] Shemen ʻarev = The poems of Mordecai Dato. Two poems of Immanuel Frances, edited for the first time from a MSS in the British Museum [today at the British Library], by A.W. Greenup. London, 1910.

[10] https://www.nli.org.il/en/books/NNL_ALEPH990017512250205171/NLI. In addition, the song appears in various manuscript copies, some of them including only ‘Le-El ‘Olam’ in square Hebrew letters, a further testimony to its wide early diffusion among Italian cantors. See: New York, Jewish Theological Seminary of America, Ms. 10211; New York, Columbia University Library, Ms. X 893 J 748; Cincinnati, Hebrew Union College Library, Ms. 230 London, The British Library London England Or. 10471 (formerly in the possession of Rabbi Moses Gaster); Jerusalem, Umberto Nahon Museum of Italian Jewish Art, Ms. ON 1528; Jerusalem, Meir Benayahu Collection, Ms. V 151; Jerusalem, Library of Mossad ha-Rav Kook, Ms. 1146; Rochester (USA), Abraham Karp Collection, Ms. 18; Jerusalem, Michael Krupp Collection, Ms. 4162 (apparently copied by a child as an exercise in Hebrew writing) and more.

[12] For the Pesaro community, see the following manuscript https://www.nli.org.il/en/manuscripts/NNL_ALEPH990001089150205171/NLI#$FL164113961