Meir Shimon Geshuri (née Bruckner; April 19, 1897 - December 9, 1977) was an Israeli researcher of Jewish music with emphasis on the study of Hassidic music traditions. He was also a public figure, being a significant activist in the Hapoel Hamizrachi movement, a religious socialist party within the Zionist movement. A thorough evaluation of his significant contributions as a scholar is still a major gap in the historiography of Jewish music.

Born in Myslowitz, Upper Silesia, then part of the German Empire (now Mysłowice, Poland), Geshuri (a name derived from the Hebrew for “bridge,” an equivalent of the German “Bruck”) was the son of Fruma bat Tzvi and Gita Langer and R. Eliezer Bruckner (1864-1933). Eliezer (aka “Lejzor”) was a merchant but also a cantor (Geshuri describes him in his memoire [Geshuri 1970, 1] as “yode’a naggen,” i.e. conversant in music and “ba’al tefillah muvhaq” i.e. a consummate prayer leader). He was a descendant of a family of cantors and singers associated with Hassidic courts in Poland, most especially with the court of Rabbi Haim Shmuel Horowitz-Szternfeld (1843-1917), the Rebbe of Khantchin (or Chentchin; Chęciny, South Central Poland). In the introduction to his major publication, Haniggun vehariqud bahassidut(Music and Dance in Hassidism, 1956), a work discussed in more detail below, Geshuri acknowledges the Hassidic background of his youth:

From the Tzaddik Rabbi Haim-Shmuel Halevy Horwitz of Khantchin near Kielce, grandson of the Seer of Lublin, who was Rabbi of all of my father’s family, I acquired my fondness for the Hassidic niggun. In my memory are always present some of the visits that I made accompanying my father R. Eliezer Bruckner and my grandfather R. Abraham Mordecai Bruckner from Skała-Wolbrom [i.e. his grandfather had immigrated from northern to southern Poland] with six of his sons and his sons-in-law to the court of the Rebbe in Khantchin during the High Holidays, the visits of the Rebbe to our residence in Mondziov-Sosnowiecz [a suburb of Katowice and a relatively new Jewish settlement in Silesia] next to the Prussian border during [the Rebbe’s] journeys to the springs in Marienbad in Austria and the friendly relations between us and the Rebbe’s songs, Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel (may God avenge his blood), the Rebbe of Olkusz.

Embedded in this testimony is an inner tension between Geshuri’s allegiances to the Hassidic heritage of his family, originating in the frontier with Belarus, and his exposure to the Haskalah and modern German culture that spread to the new Jewish settlements of Silesia:

Naturally, living on the borders of the German Upper Silesia and the Austrian Western Galicia made it easy for me to think of acquiring an education. The praise of Moses Mendelssohn, the champion of Haskalah, came to me from Berlin… and from Vienna, capital of Austria, we got word of Peretz Smolenskin, editor of ‘Hashahar’ and author of Haskalah books that served as a bridge to the new national-Zionist period. (Geshuri, 1970, part 1, 1)

Geshuri began to show interest in music as a young child, assisting his father at the synagogue and showing an impressive gift to memorize niggunim. After his father closed his grocery shop in Niwka (in the face of new competition), the family settled for a few years in the adjacent Dańdówka, a small village with no Jewish residents at the time. In his unpublished memoir, which is structured as a musicologist’s Bildungsroman ('From the Notebook of a Writer-Musicologist,” circa 1970), Geshuri described his early childhood in the all-Christian Dańdówka in terms of extreme musical isolation and alienation. Hendel-Malka, Geshuri’s aunt from his father’s side, came to live with the family in Dańdówka and took charge of raising the children. Through Hendel-Malka, whom Geshuri considered a mother, he became acquainted with a vast array of popular and traditional Yiddish songs, as well as, later on, the new “rebirth” songs (Shirat Hatehiya, i.e. Hebrew songs of Zionist content). Since there were not enough Jewish children in Dańdówka to form a heder (elementary school), Geshuri was sent to study in nearby Niwka, and later on attended the Yeshiva in Brest, on the frontier between Poland and Belarus (formerly Brest-Litovsk,Brisk De-Lita in Yiddish).

However, Geshuri’s life, as those of many young yeshiva students, took a turn towards Zionism. As he mentions in his memoir, his household’s bookshelf was rich in Jewish (especially Hassidic) literature, but also plentiful with maskilim and Zionist literature. He moved to Berlin, the rapidly growing hub for Eastern European Jews seeking modern education, studied at a gymnasium and then at the city’s University and the Conservatory of Music. He eventually moved to the Dresden Academy of Arts and the Technikum in Vienna.

Following his studies abroad, Geshuri returned for a short but productive time to his motherland after World War I. He was a member of the regional leadership of the Mizrachi Youth in Silesia and Zagłębie regions in Poland. He established Zionist associations for the youth dedicated to combat growing assimilation among the children of well-to-do Jewish families in the coalmining regionof Upper Silesia.

Geshuri immigrated to Eretz Israel in 1920. Upon arrival, he worked as a laborer, paving the Tabha-Rosh Pina road in the Upper Galilee, but not for very long. He soon moved to Jerusalem where he joined the “Hasolel” printing press as a typesetter. At the same time, he started his copious and life-long journalistic work, eventually publishing articles in several periodicals: 'Doar Hayom,” the revisionist “Ha’am,” and “Hator,” the weekly publication of the Mizrachi movement printed in Warsaw, the liberal “Haaretz” and “Hatzofe,” the daily newspaper of religious Zionist movement in British Palestine. Overall, Geshuri published about eight hundred and forty articles from September 1921 to late 1969, the vast majority of them on issues related to Jewish music, and contributed to the Jewish press in the USA and South Africa.

In 1922 Geshuri was one of the founders of the Hapoel Mizrachi movement, which split off from the religious Zionist Mizrachi movement under the “Torah ve’Avodah” (Torah and Labor) banner. He served as secretary general of this new political organization, as well editor of the movement's newspapers: the “Hapoel Mizrachi” magazine, the bi-weekly “Netiva” and the “Torah ve’Avodah” journal. He was elected by the movement to serve as its representative in Zionist congresses (Carlsbad, 1923 and Zurich, 1929). At the World Conference of the Mizrachi that convened in Antwerp in 1929, he was elected honorary secretary of the movement. He also served as the treasurer of the Religious Writers Union (Iggud Hasofrim Hadatiym) and as secretary of the union of the printed press workers in Jerusalem.

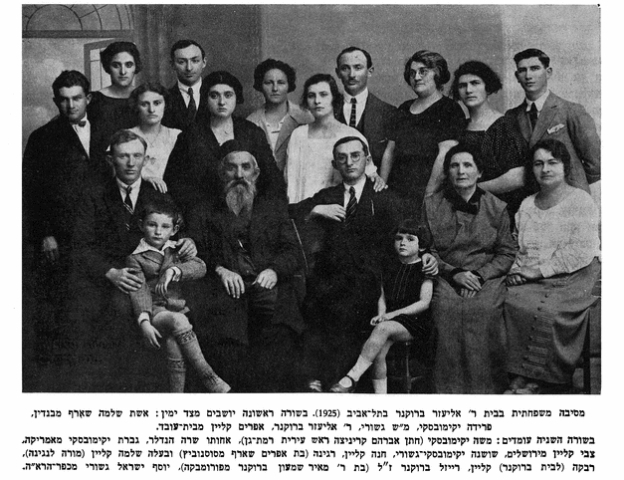

Geshuri (first row, third from right, with glasses) and family in Tel Aviv, 1925

From local unionist and political activist he moved into public life, in Jerusalem and on the national stage. Geshuri became a member of the Jerusalem City Council and a representative at the Second Assembly of Representatives of the Jewish settlement in British Palestine (Assefat Hanivharim, see announcement in “Haaretz,” January 1, 1926, p. 6).

Eventually he became secretary of the Department of Trade and Industry at the Jewish Agency and, after the foundation of the State of Israel, occupied the same position at the Ministry of Trade and Industry until his retirement. He was also one of the founders of the Mekor Hayyim neighborhood in west Jerusalem and a member of the Beit Vegan neighborhood council.

Geshuri was among the leaders of Hapoel Hamizrachi who, in early 1935, opposed joining the Histadrut, Israel’s General Organization of Workers. Following this episode, he left Hapoel Hamizrachi and participated in an attempt to establish the 'Original Hapoel Hamizrachi' movement. Eventually he left politics, although he remained a very active member of the national religious movement, working at the Religious Zionist Archives at the Rabbi Kook Institute. In addition, he was one of the founders of the Institute for Religious Music, which was later renamed Renanot, the Institute of Jewish Music (Zimmerman 1972). In 1956, the Tel Aviv municipality bestowed upon him the Engel Prize in recognition for his contributions to music research.

Geshuri died in 1977 at the age of 80. His archive, containing a vast collection of music manuscripts, books and articles, correspondence and documents, is located in the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem.

Geshuri’s Contributions to the Study of Jewish Music

Undoubtedly, Geshuri’s main legacy is his copious output on Jewish music, including a dozen books and hundreds of essays. Evaluating this vast corpus is beyond the scope of this text. We shall therefore summarize the main tenets of his work, mostly based on his foundational and ambitious publication, Haniggun vehariqud bahassidut (1956).

As we have seen, Geshuri’s early exposure via his father’s family to Hassidic circles in Central Poland certainly prepared him for his deep interest in documenting and researching Hassidic music later in his life. At the same time, his musical education in Berlin and Dresden opened before him the world of classical Western music. One of his very early articles in the Hebrew press in Palestine appeared in Itamar Ben Abi’s daily “Doar Hayom,” under the title of “Beethoven, the Artist and the Creator” (January 13, 1922). This piece already reveals an inherent tension in Geshuri’s approach to the music and Jewish nationalism issue, namely the aspiration to engage with great musical art as a universal edifying ideal, in conflict with his yearning to understand music in terms of discrete national identity. In the first part of this article he stresses past Jewish contributions to the Western musical canon (Felix Mendelssohn and Anton Rubinstein) and to classical music performance during his own period. At the same time, he complains that all these musicians of Jewish extraction are “adopted” by their countries of origin as one of their own. Put differently, the Jewish musical narrative loses its standing due to the “loss” of its geniuses to other nations. Gradually, however, Geshuri ceased to write about general music and focused exclusively on Hassidic and, later, on non-Ashkenazi Jewish musical traditions too.

Further adding to the internal tension in Geshuri’s music writings is his early engagement with the creation of a Zionist musical language. In this context, his association with the avant-garde composer Mordecai Sandberg (1897-1973) is remarkable. In 1930 Sandberg and Geshuri established the short-lived music journal “Hallel” (only three issues appeared), published under the umbrella of the Israelite Institute for New Music (Hamakhon hayisraeli linginah hadasha), an ephemeral institution. Notice the use of the novel term yisraeli instead of “Jewish” or “Hebrew,” which heralded a modernist approach in attempting to avoid the semantic terminology associated with the diasporic past or the more recent Zionist establishment, while maintaining a taste of biblical antiquity. This music institute would be the first of several initiatives in the field of music education which Geshuri would be involved with during his lifetime.

At the same time, Geshuri became a member of a growing circle of immigrant Jewish musicians in Palestine who were promoting the creation of an idiosyncratic vernacular musical language which aimed to be extrapolated (but distinct) from diasporic musical traditions. However, what distinguished Geshuri from most of the composers and educators engaged in this new mission was his passionate affiliation with the religious-national sector, which factored into his unique approach to this creation of a new musical language.

Geshuri’s early ideas about Jewish national music in Palestine were articulated (clumsily one must say) in his 1930 series of essays published as Renanot (Geshuri 1930). Two quotes will suffice to show his allegiance to ideas similar to those exposed by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, a figure Geshuri respected but also criticized (see the Geshuri-Idelsohn correspondence in the Appendix below).

It is the duty of the [music] teachers [in Palestine] to remove from the sanctuary of Hebrew culture the “community of the exiled ones” with its mixture of [music from the] peoples within which [Jews] dwelled and to introduce instead the song that provides a faithful expression of the Jewish people and revives before us that great and distant past with the immediate future… so that they will have the capacity to write down the melodies correctly or their independent ideas that emerged from the environment of the Land of Israel and in order to impart to the young generation the song of [the Land of] Israel and to create in the [new Hebrew] music an original national atmosphere. (Geshuri 1930, 8)

Embedded in this convoluted passage is the Idelsohnian core idea of a modern revival based on an ancient Jewish national musical past. Not surprisingly for his period, Geshuri found such an ancient repository in the Yemenite Jewish musical traditions. But in addition, and unlike most Zionist musical activists at that time, he found an affinity between Yemenites and Ashkenazi Jews from Poland (i.e. not from Germany!), a connection that will later allow him to claim Hassidic music as a major fountain of inspiration for national revival:

The question is, the music of which Jewish-diasporic community is closer to the Hebrew source… in the music of the Yemenites we find many share roots with the Ashkenazi music from Poland. From this, we have the evidence of the antiquity of both the music of the Ashkenazim and of the Yemenites… It is allowed to decide that these shared bases between the music of the Ashkenazim and the Yemenites go back to antiquity, i.e., they are remnants of the ancient Hebrew music from before the destruction [of the Jerusalem Temple], and from them we can assume with certainty about the very essence of the ancient Hebrew music (Geshuri 1930, 4-7)

Geshuri was also quick to disseminate his musical ideas in the mass media, through his radio broadcasts in “Kol Yerushalaim” (Voice of Jerusalem), the radio station established during the British Mandate. Echoes of his late 1930s’ broadcasts in the Hebrew printing press are illustrative of Geshuri’s navigation between ethnography and modern creativity. “Hatzofeh,” on August 12, 1938, reported on a radio program by Geshuri dedicated to the niggunim for the Ninth of Av, on the aftermath of that holiday. The author of the feature (using the pseudonym of A. Sh-T) reported that the broadcast included a lecture by Geshuri, accompanied by live demonstrations by “the studio’s musicians and Mister Kum.” The reporter harshly criticized the “long talk about matters that by no means have any educational benefit” instead of talking about each niggun. Niggunim, he added, is a subject about which “Mr. Geshuri certainly knows… its value and spread among the people; who like him feels the extent to which this medium is good and fit as a primary tool for dissemination [of information about the niggun].” The author recommended that Geshuri free himself from the “folkloristic-scientific tendencies” of his radio lectures in favor of something more “educational.” In the whole program, he complained, Mr. Kum sang only one niggun (“Beleil zeh yvkayiun”) solo, while the rest of the examples were performed musical accompaniment, including verses from the Haftarah and other “folk or synagogue songs that the Hassidim have no interest in, and they are not at all performed among them.”

The knowledgeable reported noted that the performers and Mr. Kum added a “Hassidic touch” to their examples and they succeeded quite remarkably, especially in the verses of the Haftarah, but in spite of this, the only “real” niggun performed was one which he defined as “a profound composition of Habad, attributed to R. Mikhael Hazaken who was close to the Middle Rebbe, and it was performed without text with great devekut.” The Hassidim call this melody “The Wailing Mother” (“Ha’em hameqonenet”; Yiddish: “Di klog muter”) and “Mr. Kum breathed into it a ‘material’ (gashmi) life by adapting it to the dirge (qinnah)… and not without success.”

This report reveals several aspects of Geshuri’s public activities, firstly, details about the network of musicians involved in programs of Hassidic music at the time. There is no doubt that Geshuri selected the materials for the program, but for their instrumental arrangements he most probably counted on the collaboration of Hans (Chanan) Schlesinger (1893-1976), a key figure in the Hebrew music section at the Voice of Jerusalem. In a report about another radio program, dedicated to the broadcast of a concert “in memory of the Besht [R. Israel Baal Shem Tov, the initiator of Hassidim],” published in the newspaper “Haboker” just weeks earlier (July 4, 1938), the writer (M. Navon [Kluger]) actually complained about the absence in this program of Geshuri’s live lecture, and Kum’s voice exemplifying it. All the instrumental arrangements in the concert by Schlesinger “lack the sweetness and the power of expression of the Hassidic niggunim,” he went on to say, while noting that “not all the niggunim are by the Besht.”

One can see just in these two reports a hint of the network of actors with which Geshuri interacted. It includes extremely knowledgeable critics, a professional German Jewish musician recently arrived to Palestine (Schlesinger), the notable menaggen “Kum” from Habad, whom we can identify as Eliyahu Kum (1899-1987; see Mazor 2004, pp. 30-31), and an attentive and dedicated audience. Geshuri’s radiophonic interventions in the field of Jewish music were also significant because they took place during the same period as broadcasts by the famed ethnomusicologist Robert Lachmann, another exiled German Jew. While Lachmann’s programs on “Oriental Music” in the Mandatory radio station received due scholarly attention in recent years (Katz 2003; Davis 2013), Geshuri’s efforts in the same field still await assessment.

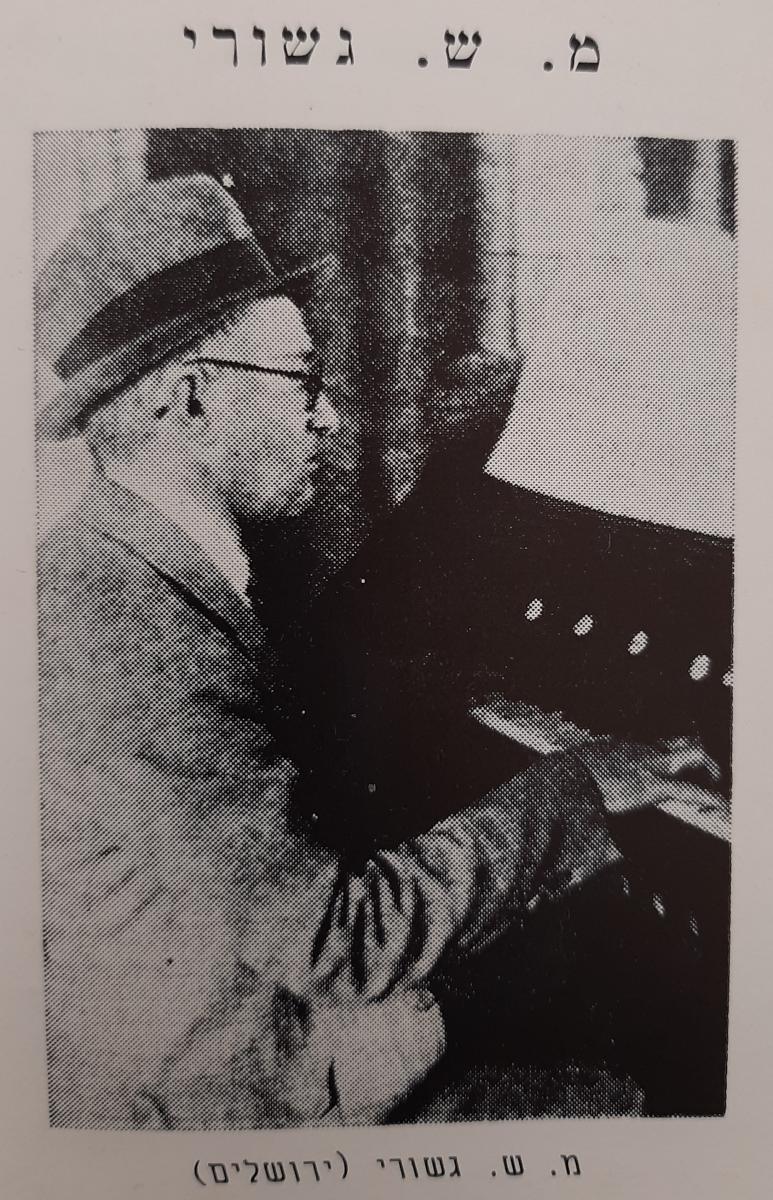

Geshuri playing the harmonium, c. 1950s

Aside from his journalistic and mass media efforts, Geshuri’s main opus is his encompassing research on Hassidic music, a subject that, as we have seen, occupied him most of his life. The culmination of his efforts was his unfinished Haniggun vehariqud bahassidut, of which only three volumes appeared (1956, 1959, 1959). These volumes were intended to be the first of an encompassing Encyclopedia of Hassidism printed by “Netzah – Traditional Literary Institute,” which never materialized. The encyclopedia was intended to “cover all aspects of Hassidic existence” as a corrective to the “distorted evaluation that affects pseudo-Hassidic research.” This ambitious promise remained on paper.

As we have seen, his research efforts were well underway in the pre-war period. He had published large amount of articles on Hassidic music in the Jewish press of four continents (Palestine, Poland, South Africa and the USA), especially the series of articles titled “Lekorot haniggun hahassidi” (“Towards a history of the Hassidic niggun” 1930-1937) and produced, as we have seen, radio broadcasts. Moreover, in 1936 Geshuri launched his first major publication, a collection of articles on Hassidic music penned by himself and by other writers that appeared as Lahassidim mizmor published by the Hathiya press in Jerusalem.

Lahassidim mizmor appeared as a “literary and cultural journal for religious-folk music of the Hassidim, with musical notations and facsimiles of Hassidic personalities.” The publication was sponsored by “the board of the Devotees of Hassidic Music,” an organization whose existence is attested only by its mention in this collection. These 166 pages in total represent one of the earliest significant contributions to modern Hassidic music research. Geshuri’s reflexive historical awareness lead him to declare himself a pioneer, disregarding publications on the topic by his predecessors (with the exception of Abraham Ber Birnbaum, whom Geshuri greatly admired), even though he was extremely well-informed about them, as testified by the impressive bibliography of Hassidic music studies which appeared at the end of La-hassidim mizmor.

Geshuri’s introduction to Lahassidim mizmor (titled “Im ha-tzlil ha-rishon”; “With the First Sound”) not only emphasized the urgent need to document and study Hassidic music, it also framed this activity in a Palestine-centered perspective, and stressed the author’s deep commitment to the Jewish national renaissance in the Land of Israel in the religious vein of the Hapoel Hamizrachi political movement. Geshuri strongly emphasized the “Oriental” character of the Hassidic niggun that originated, in his opinion, in the early Hassidic immigration to Ottoman Palestine. This musical “Orientalism” finds its expression particularly in the niggunei devekut (tunes of mystical cleaving), “that is the tune of the soul, from which one can hear the trembling of the elegiac tone of the nation.” This “Oriental character” also facilitated the turning of the Hassidic niggun into a genre of folk music. Moreover, the niggun in the renewed Jewish settlement “is carried in the mouths of the youth of Israel who awake and immigrate (lit. “ascend”) to the Land of Israel to stir [the land] from its barrenness and to build it.[…] The Hassidic niggun accompanies the individual who walks in the field after the plough and the laborer in the harvesting of citrus.”

Interestingly, the turning of the Land of Israel in general and the city of Tel Aviv in particular into a new center of Hassidic niggun renewal is related to Geshuri’s emotional appeal to the Rebbe of Modzitz, R. Shaul Yedidiah Taub (1886-1947), to settle permanently in the modern Hebrew metropolis. Indeed R. Shaul visited British Palestine four times (1925, 1935, 1938, 1947) and called for the strengthening of the Jewish community there, but ultimately settled his court in New York. Yet, he died in the Land of Israel during his last visit, on the emblematic day of November 29, 1947, the day the UN voted for the partition of Palestine. Be as it may, Geshuri’s admiration for the creative musical skills of R. Shaul, and his pioneering publication of a selection of the Rebbe’s tunes in musical notation, contributed to cementing the uniqueness of Modzitz in the historiography of Hassidic music.

Geshuri’s opening article in La-hassidim mizmor, titled “Erkhei neginah ba-hassidut” (“Creeds of Music in Hassidism”), offered a general view of the field as well as a program for its study, and in particular stressed the strong relationship between niggun and dance, as well as some of the major trends of the Hassidic niggun. The kernel of his ideas maturated in the following years, including the war period, leading to the aforementioned Haniggun vehariqud bahassidut.

One has to contextualize Geshuri’s ambitious enterprise of the 1950s in the framework of post-Holocaust trauma. What was initially seen as a national religious revivalist project aimed at relocating the center of Hassidic music to Israel and turning the niggun into a national music, beyond the walls of the Hassidic courts, tuned into a project to save the musical remnants left by the cataclysmic physical devastation of the Hassidic centers in Europe.

In the first volume of Haniggun vehariqud bahassidut Geshuri announced that five volumes on music and dance were in the making, while in the second volume he raised the number to seven. This enlargement of the project was connected to his growing accumulation of materials. Geshuri’s model was Idelsohn’s Thesaurus of Oriental Hebrew Melodies (Otzar neginot Yisrael in Hebrew), to the point that he considered calling his work Otzar neginot hahassidim (Geshuri 1956, p. viii). The organizing principle of the publication was a mixture of spatial arrangement (geo-political units existing prior to World War I) and a diachronic approach, in which the music of Hassidic dynasties within a specific territory was discussed according to the date of their establishment. Within each chapter Geshuri proposed to discuss two types of sources: the niggunim themselves and texts concerning niggun, or in his words, “ideas, exempla, proverbs, written stories and oral narratives.”

The original layout of five volumes included two volumes dedicated to the territories of “the large czarist Russia until 1914,” comprising the territories that became part of Poland after World War I. Two volumes were needed due to the sheer amount of Hassidic courts in that vast area, and to properly document the remaining musical memory which survived the destruction caused by the right (Nazism) and the left (Communism/Bolshevikism).

Volume three was to be dedicated to Eastern and Western Galicia, Hungary, Bukovina and Old Rumania. Volume four included Congress Poland, which had to be separated from the Russian volumes due to space considerations. The fifth and final volume was intended to include Hassidic music from America and the Land of Israel. In volume II he did not specify how the materials were supposed to be rearranged in seven volumes. As already mentioned, only three volumes appeared, all dedicated to Hassidic music in the territories of the Old Russian Empire. The rest of the materials remained scattered in newspaper articles or unpublished in his archive.

An analysis of the introduction to the first of these three volumes provides a succinct manifesto of Geshuri’s main tenets (Geshuri 1956, vii-xii). His core goal was to unravel the “torat haniggun hahassidi,” which can be translated as “a theory of Hassidic music.” This theory was concealed in a massive array of texts and musical practices that until his time, he claimed, were studied in a very fragmentary way, an argument Geshuri had already advanced before the war. His predecessors lacked the analytical tools and historical perspective to study the “torat haniggun,” and moreover, the Hassidim themselves focused on practice rather than commentary (ma’aseh over midrash in his words), and thus they did not develop a consistent theory of music. In addition, the Hassidic niggun, if one tackles all Hassidic dynasties and historical periods, comprises a vast portion of the field of religious Jewish music. Thus, in light of the Holocaust and his desire for the niggun to have a central part in the national music of Israel, the mission to document it became all the more urgent.

Geshuri’s remarks are also interesting for their contribution to the development of music research in Israel. His positioning in the emerging Israeli musicological scene after the creation of the state was a defensive one. He defined himself as a halutz, a pioneer who “starts small and develops into [engaging in] big” endeavors (Geshuri 1956, ix). He wrote, “I am entitled to state that for the first time the readers are being presented with a complete book that covers all of Hassidism [including] its dynasties and geographical centers.”

His dedication to the cause knew no limits. He worked on the book without interruption during the war “without attending to the bombs of the enemy around even during the days of Al-Alamein.” Moreover, he stressed the unique nature of his work: “I even hesitated [to publish on Hassidic music], waiting for others to carry out this task.”

Geshuri felt that Jewish musicians of the previous generation, who could have done something, dedicated their efforts in other directions. Pinchas Minkowski for example, “a typical Hassid of R. Dovidl of Tolna,” and Abrahan Ber Birnbaum, “the cantor of Čenstochová who originated in the Gur dynasty,” did not take upon themselves “the great mission” (Geshuri 1956, xi). Moreover, the attempts made in this field were unsatisfying, in Geshuri’s opinion. In volume 10 of the Thesaurus of Oriental Jewish Music, dedicated to the Hassidic niggun, the “great scholar of Jewish music, Abraham Zvi Idelsohn,” failed in the task “due to his lack of understanding of Hassidism, he mixed the topics [apparently a hint to the inclusion of Palestinian Hebrew songs is this volume] and produced a lacking work.” (This open, post-mortem criticism of Idelsohn was heralded by their personal letter exchange; see Appendix below). Before he perished in the Holocaust, folklorist Menachem Kipnis was an admirer of Karlin dynasty niggunim but his articles on this subject in the Warsaw Jewish press were incidental. Finally, gifted musicians emerged from the Hassidic ranks, but they “departed from their source and moved to the secular camp, forgetting the wellsprings of their upbringing. Even to the Land of Israel arrived some talented musicians from Hassidic circles who neglected the niggun and dedicated themselves to worldly music.”

Yet, in spite of all his self-praising statements, Geshuri was always on the defense, as we have already seen in the introduction to his pre-war publication and in the criticism against his “scientific” approach. His prolific writings, richly informative as they are, lack scholarly rigor. He rarely spells out the sources on which his statements are based and many of his historical assumptions are problematic to say the least. It is thus remarkable that Geshuri does not mention any of the Jewish musicologists active in British Palestine, such as Salomon Rosowsky, Robert Lachmann, Itzhak Edel, Peter Grandewitz, Moshe Gorali (Bronzaft) or Menashe Ravina, who did not delve into the subject of Hassidic niggun to the extent that he did, or at least did not see the niggun as the epicenter of Jewish music. After the establishment of the State of Israel, figures such as Edith Gerson-Kiwi and Hanoch Avenary started to make their inroads into the academic establishment. One may argue that in contrast to Geshuri, these figures did not belong to the national religious social circles. However, even a figure coming from the national religious sector, such as ethnomusicologist Avigdor Herzog, who arrived from Hungary after the Holocaust, could have cast a shadow on Geshuri’s scholarship. This contextual tension is apparently behind the following disclaimer included in the introduction to the opening volume of Haniggun vehariqud bahassidut:

This book is not intended for specialists but to lovers of Hassidim and music without demanding great efforts from their side. The book does not demand previous knowledge of music but introduces [the reader] to this world, opening his eyes and uncovers the hidden in an understandable, pleasant literary language that can reach the hearts of any Hassid or music lover (Geshuri 1956, xii).

Geshuri was not alone in the field of Ashkenazi traditional music documentation and study during the early years of the State of Israel. Other distinguished Israeli musicians engaged in music research without formal academic background, with diverse degrees of success. The name of klezmer and Yiddish song researchers Joachim Stutchewsky and Moshe Bik, both of whom share with their contemporary Geshuri a similar life path, come to mind in this context. Put differently, two strands of “musicology” developed parallel in Israel, one academic and one popularizing. They were both engaged in the national project. Their differences were at the level of methodology, rigor and institutional belonging.

Geshuri’s didactical and popularizing approach to writing about Jewish music is laid bare in the first section of Haniggun vehariqud bahassidut, titled “History of religious music in Israel.” This tour de force text, which in a mere 107 pages covers a period from Biblical times and to the modern national revival, does not include a single reference to any previous writings. It is just a prolegomenon to the “real” chapter of Jewish music’s history, the emergence and development of the Hassidic niggun.

Finally, Geshuri’s emphasis on the Hassidic niggun did not totally lead him away from other aspects of Ashkenazi music or the musical traditions of non-Ashkenazi Jews. For example, his relentless drive to create a unified national liturgy led Geshuri to support various initiatives aimed at establishing schools for the cantorial arts. He collaborated with the distinguished cantor and composer Shlomo Ravitz in the publication of an Anthology of Traditional Israeli Hazzanut for the Whole Year (Antologiya israelit masoratit lehazzanut. Tel Aviv: Youth and Student Synagogue of the Bilu School and the Sela Seminary for Jewish Studies, 3 vols., 1964).

Geshuri also published many essays on the music of the Sephardic and Oriental Jews (especially on the Jews of Kurdistan), some of which provide valuable ethnographic data unavailable in other sources. This interest in non-Ashkenazi Jewry is shown in his correspondence with Idelsohn from the early 1930s (see Appendix below), and was part of that “heroic” effort to gather a complete documentation of Jewish musical memory.

The succinct evaluation of Geshuri’s contributions to the study of Jewish music presented here is just a very preliminary, initial incursion into his life and work. The vast bibliography of his publications (Cohen 1966) and his voluminous archive at the National Library of Israel offer an open invitation to study one of the most idiosyncratic musical scholars to emerge during the formative period of Israeli Jewish musicology. As Geshuri mentions in one of his letters to Idelsohn (below), he collected about one thousand niggunim, and this number is not an exaggeration as his more than sixty handwritten music notebooks in the archive show. Interestingly, most of the active users of Geshuri’s collection are young Hassidim who are in search of the “authentic” and “lost” niggunim of their respective dynasties’ repertoires.

Modernism and religious nationalism, popularizing tendencies and thoughtful scholarship, art and faith all converge in the complex figure of Geshuri. It is therefore the task of future historiographers of Jewish music to assess his work in a more comprehensive manner.

Appendix: The Geshuri-Idelsohn Correspondence

Idelsohn’s archive at the National Library of Israel holds letters that Geshuri sent him during 1930-1933. It seems that Idelsohn (at the time based in Cincinnati for almost a decade) initiated the correspondence and sought Geshuri's assistance in publishing the second volume of his Toldot Hanegina Haivrit (History of Hebrew Music, only volume 1 had appeared in 1924; the remaining volumes are unpublished). Idelsohn’s letters to Geshuri, as far as we know for the moment, are lost. This documented correspondence, even if partial, is very significant to our understanding of Geshuri’s mission, as well as in appreciating to what extent Idelsohn’s work affected enterprises in Jewish music scholarship after the 1920s.

This epistolary primarily reveals Geshuri's complex attitude towards the esteemed senior scholar: on the one hand, he approaches Idelsohn as a venerated “mentor” and posits himself as a comrade in Idelsohn’s “war” for the cause of original Hebrew music. On the other hand, Geshuri expresses a clear consciousness of his superiority—as one who operates in the actual “battlefield” of Hebrew music—in contrast to the “exiled” Idelsohn (“To conduct a war, the generals must be present in the war”). Geshuri, who has just reprinted a short article by Idelsohn in the second issue of the journal Hallel, informs Idelsohn that he did not fail to mention his name and to quote his work in his articles, and implores Idelsohn to send new articles for the upcoming issues. At the same time, Geshuri is not afraid of criticizing Idelsohn’s decision in the Thesaurus to transcribe “oriental” melodies in Western notation:

Notwithstanding his great accomplishment in the study of Hebrew music, one cannot accept his manner of transcription. He has already shown that the East could not be contented with the European notation … and still, he wrote the melodies of the Yemenite Jews, Sephardi Jews, etc. in European notation. How can one say one thing and do another? This cannot hold. (Geshuri, 3.7.1930)

Later in the correspondence, Geshuri adopted an even bolder position towards Idelsohn, especially on the topic of Hassidic music. In a letter from 26.1.1933, Geshuri informed Idelsohn that he too has been working tirelessly to collect and transcribe “the folk melodies of the various Jewish ethnic groups.” He reported that most of the material belongs to the Hassidic repertoire and boasted that he has gathered 800 Hassidic melodies (divided into 35 categories), in addition to a vast collection of historical material. Geshuri asked Idelsohn’s assistance in publishing his collection, and admitted that he was unable (and unwilling) to provide the necessary funds.

It appears from these letters that Geshuri was unaware at the time of the not-so-recent publication of Vol. 10 of Idelsohn’s Thesaurus, dedicated to Hassidic niggun, and his appeal can be interpreted a suggestion that Idelsohn might use Geshuri’s 800 Hassidic melodies, or at least include some of them, in the Thesaurus.

From the next letter (9.3.1933), we learn that Idelsohn wrote back to let Geshuri know that the Thesaurus has already been published in its entirety. Moreover, in his reply, Idelsohn accused Geshuri of plagiarizing a relatively recent article he wrote on the Hassidic music (“Haneginah haḥasidit,” Sefer Hashanah: The American Hebrew Yearbook 1 [1931], 74–87). Geshuri dismissed the accusations (“in vain you cast suspicions on me”) and claimed that his article was written many years ago and laid at the publisher’s desk, ready to be printed even before the appearance of Idelsohn’s article. In Geshuri’s eyes, it is Idelsohn’s article that contained a large portion of his own article, not the other way around. Geshuri once again reassured Idelsohn that he always refers his readers to Idelsohn’s work, even though he never made any use of the Hassidic niggunim published by Idelsohn in his own studies. Again, he expressed his willingness (and capability) to assist Idelsohn in the publication of Toldot’s second volume, and endedthe letter with a request that Idelsohn will provide him with a copy of the complete (and costly) Thesaurus series.

In 13.7.1933 (the last documented letter in this correspondence), Geshuri replied to a recent letter by Idelsohn, who suggested a new solution to Geshuri’s problem: the various Jewish melodies that Geshuri was able to collect and transcribe might find their place in a future supplement volume of the Thesaurus (no such volume was ever published). This time, Geshuri’s reply was far more aggressive and “territorial.” He outright rejected Idelsohn’s proposition, asserting that “my melodies alone will occupy two thick volumes.” He stressed the fact that with extreme efforts, he was able to link each melody to the specific Hassidic court from which it originated and that this endeavor (largely neglected by Idelsohn) is key to a full appreciation of the Hassidic niggunim. The letter ended with the recurring request for copies of the Thesaurus (with a specific reference to Vol. 10).

However, by now, the part-time music “enthusiast” (as Geshuri described himself in one of the letters) who at the beginning of the correspondence spoke as a humble follower, faced Idelsohn from a position as a rival scholar. His collection of Hassidic niggunim, Geshuri wrote, is expanding by the day (and it soon will reach a thousand). Moreover, Geshuri informed Idelsohn that he was approached by a group of “German musicians who are refugees from Himmler,” which the government of Eretz-Israel (probably a reference to the Jewish Agency) has appointed with the task of investigating all aspects of music in Eretz Israel and the East. These musicians wanted him to write down the melodies of the many ethnic groups living in the country (those that have not been published yet). A new music institute would be established soon, and Geshuri was asked to travel abroad to collect Jewish material for it.

From the proud and optimistic tone in which Geshuri ended his letter (“there is hope for the future of Hebrew music and for his [i.e., Idelsohn’s] great endeavor”), it seems that a copy of Idelsohn’s magnum opus is needed in Eretz Israel, not because it contained the authoritative and conclusive treasure of Hebrew music, but in order to avoid unnecessary duplication. Such repetition might delay a new and far more ambitious scientific project that in many respects had only just begun (“I will somehow need to purchase the Thesaurus volumes, in order not to write the same melody twice”).

Sources arranged by date (all items are in Hebrew)

Geshuri, Meir Shimon, Renanim: maʼamarim ʻal hamusiḳah ha’ivrit: ḳevutsah rishonah, Jerusalem, 1930.

Sandberg, Mordecai and Meir Shimon Geshuri, Hallel. Jerusalem: Hamakhon hayisraeli linginahhadashah, 1930.

Geshuri, Meir Shimon, Letters to Idelsohn: 3.7.1930; 26.1.1933; 9.3.1933; 17.3.1933. Idelsohn Archive, Mus. 4 E (522, 201, 202, 203), Department of Music, National Library of Israel.

“Geshuri (Bruckner), Meir Shim’on,” in David Kala’i (ed.), Sefer ha-ishim: Leksiqon Eretzisraeli. Tel Aviv: Masada, 1937, p. 150.

“Geshuri (Bruckner), Meir Shimon,” in David Tidhar ed. Entsiklopedyah lehalutse hayishuv uvonav, 3 (1949), p. 1208-9; 15 (1966), p. 4799.

Geshuri, Moshe Shimon, Music and Dance in Hasidism. Jerusalem: Hathiyah, 1956.

Cohen, B. M. Bibliography of published works on Jewish music from M. S. Geshuri: bibliographical sketch, 1922-1966. Jerusalem: Institute of Religious Music, 1967.

Geshuri, Meir Shimon, “From the Notebook of a Writer-Musicologist (Musings and Memories)”, 2 parts: 11, 19 pp., undated (circa 1970), Mus 56 B 80, Department of Music, National Library of Israel.

Geshuri, Moshe Shimon, “Pirqei zikhronot,” Tatslil 12 (1972), 72-74.

Zimmerman, Akiva, “Zikron rishonim,” Dukhan 13 (1991), 136-138.