Niggun ‘Akedah is an Ashkenazi melody firmly associated with the Binding of Isaac, which was sung to texts in both Hebrew and Yiddish. Many of these texts touch directly upon the biblical story, while others refer to the traumatic memory of the Crusades, and to other themes, as will be shown below. Strongly affiliated with the liturgy of the High Holidays, the Niggun ‘Akedah served as a symbol, provoking ipso facto strong emotional and religious feelings among listeners. Surprisingly, this topic has been the subject of little scholarly attention, despite the significant number of transcriptions bearing the title ‘Akedah, and notwithstanding recent publications of intricate cultural-historical scholarship concerning the Binding of Isaac within the context of the Crusader massacres (Fraenkel, Gross, and Lehnardt 2016; Haverkamp 2005; Assis 2000).

Our study reviews the great significance of the ‘Akedah narrative in Ashkenazi culture, as expressed through the poems that were sung to Niggun ‘Akedah. It will assess their thematic content, formal aspects, as well as their cultural contexts and functions. Special attention will be given to verbal references to the Niggun ‘Akedah. The core of this study is an analysis of thirteen transcriptions of Niggun ‘Akedah, transcribed between 1840 and the Holocaust period, and two recent audio recordings.

The Narrative

The story of the Binding of Isaac (‘Akedat Yiẓḥak, or ‘Akedah) has assumed an important function in Jewish religion and culture since Antiquity. This renowned narrative describes how the first Jewish family (Abraham, Sarah and Isaac) came close to annihilation following God’s command that Abraham sacrifice his son. The plot is unexpectedly inverted by God's miraculous salvation of the bound Isaac, and God, in turn, commends Abraham for his obedience and promises to bless and multiply his future descendants.

The story’s primary textual rendering in the Hebrew Bible (Genesis XXII:1–19) is somewhat brief, barely referring to the characters’ feelings and thoughts, and omitting the character of Sarah altogether. Midrashic literature elaborates on the narrative at length, and it is mentioned in almost all other classic Jewish sources.[1] It has been retold by generation after generation of Jews in various vernacular languages, in both oral and written forms (Spiegel 1967, 13–16; Moreen 2000, 218–222; Guez-Avigal 2009, 159–166; Kartun-Blum 2013). Likewise, the Binding of Isaac has constituted a common motif in works of art among Jews throughout the ages (Sabar 2009, 9–27).

In Jewish Ashkenazi Culture

The Binding of Isaac maintained a key role within the Ashkenazic diaspora center that emerged during the tenth century in present day southern Germany and northern France. However, it also acquired two new layers of meaning. The first was a Jewish reclamation of the story in reaction to the Christian appropriation of ʽthe Sacrifice of Isaac,’ i.e. the typological view of the Binding of Isaac as a prefiguration of the Crucifixion of Jesus. The second layer associated the story with acts of Kiddush Hashem. (lit, the sanctification of God’s Name). It evolved following the massacres of the First Crusade of 1096, and venerated the martyrs as the spiritual successors of Isaac, regarding their sacrifice as exemplary (Cohen 2004; Assis 2000; Chazan 1996; Spiegel 1967, 7–13). These two new concepts reflect significant historical and cultural aspects of Jewish existence in trans-alpine Europe and appear to explain the narrative’s major role in Ashkenazi culture, far greater than that accorded to it by other Jewish communities (Weinberger 1998, 5–6, 184; Fraenkel, Gross, and Lehnardt 2016, 482).

According to Jewish religious practice, the passage from Genesis is recited by worshippers on a daily basis in the preliminary morning service (Birkhot hashaḥar), invoking the Binding of Isaac as a source of protection on the grounds of Zekhut ’avot , the merit of the patriarchs (Jacobs and Sagi 2007, 556-557; Shmidman 2007; Zunz 1920, i: 83–84). This passage is also ritually read in the synagogue from the Torah scroll on two annual occasions: as part of Parashat Vayera’ (Gen. XVIII:1–XXII:24), early in the annual cycle of weekly portions, and on the second day of Rosh Hashanah, because the story plays a central role in the liturgy of the Jewish New Year festival.[2]

In Ashkenazi Hebrew Literature

Medieval chronicles and Kinah piyyutim (dirges)[3] portraying the anti-Jewish persecutions which occurred from 1096 onwards often mention the Binding of Isaac. At times they depict the persecuted Jews as Isaac bound on the altar. Others connect the stories of parents killing their own children to prevent them from being forced to convert to Christianity with that of Abraham, who was willing to sacrifice his child for the sake of God (Fraenkel, Gross, and Lehnardt 2016; Haverkamp 2005; Haberman 1971). Such references contain an implicit plea for salvation similar to that bestowed on Isaac, or alternately for a reward akin to which Abraham and Isaac had received, the former for fulfilling God’s command and the latter for accepting His will.[4]

Additionally, a specific category of piyyutim (liturgical poems) relating the story of the Binding of Isaac entered the Ashkenazi prayer rite. These poems, known as ‘Akedah piyyutim, are based on midrashic interpretations and offer highly embellished poetic retellings of the story (Fleischer 2007, 470; Weinberger 1998, 223–224). They are recited during the Seliḥot (penitential) prayers, before and during the High Holy Day season,[5] lauding Abraham and Isaac (and at times also Sarah) for their pious obedience. Around fifty such ‘Akedah piyyutim exist but these must be culled from various Maḥzorim and Seliḥot anthologies.[6] It is important to stress that their unique liturgical function in the Seliḥot prayers, which appears solely in the Ashkenazi prayer rite (Fleischer 2007, 470; Weinberger 1998, 13, 184), distinguishes ‘Akedah piyyutim from other liturgical texts, including other types of piyyutim that mention the Binding of Isaac.[7]

Most of the ‘Akedah piyyutim were composed in Ashkenaz between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries (Goldschmidt 1965b, 18–19). These poems generally consist of four-line stanzas with varying number of syllables in each line,[8] and usually with the rhyme scheme aaaa, bbbb, etc. (Goldschmidt 1965b, 190 [no. 74], 209 [no. 83]). Monorhymed quatrains of this kind are characteristic of many types of piyyutim, yet they are rare in German literature (Fleischer 2007, 470; Goldschmidt 1965, 9; Zunz 1920, 86, 91). Some ‘Akedah piyyutim use the rhyming scheme aabb, ccdd, etc. (Spiegel 1950, 538–547), or aaax, bbbx, etc.[9] In addition, a number were written in rhyming couplets (Goldschmidt 1965b, 152 [no. 58], 172 [no. 66]), a form also used by the sub-genre of Seliḥot piyyutim called Sheniyyah piyyutim (Weinberger 1998, 223, 263–267, 318–319; Goldschmidt 1965b, 9), while at least one example utilizes monorhyme.[10] Still, the overwhelming majority of poems clearly indicates that the ideal form for an ‘Akedah piyyut was the monorhymed quatrain.

In Yiddish Literature

Literature composed in Yiddish also accorded the Binding of Isaac a significant role in pre-modern times (Katz 2008). A Yiddish prose adaptation of the story appears in a manuscript dating from 1511,[11] the story is mentioned within the popular homiletic work Tsene-rene (Elbaum and Turniansky 2008), as well as within various sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Yiddish epics (Dreeßen 1971, 57–58; Matenko and Sloan 1968, 13–16), Yiddish translations of Hebrew ‘Akedah piyyutim alongside Yiddish commentaries appear in Maḥzorim, etc. (see for example Maḥzor Homburg 1721 i: 86b–87b). Yet the most outstanding retelling of this story in pre-modern Yiddish literature is the epic poem Yudisher shtam (ʽThe Jewish Tribe’; Matenko and Sloan 1968, 13–16; Dreeßen 1971, 9–31; Frakes 2014, 149–155). The poem features the same monorhymed four-line stanzas used for the ‘Akedah piyyutim, yet their lines are longer than those of the Hebrew texts. However, unlike the Hebrew poems, this Yiddish poem does not appear in a Maḥzor or any other liturgical text, and its extant copies offer no indication of a liturgical function.[12]

Yudisher shtam enjoyed immense popularity in Ashkenazi society, as is evidenced by the relatively large number of versions extant today (Dreeßen 1971, 9–31; Roman 2016, 183, fn. 29), making it the most documented poem in pre-modern Yiddish literature (Shmeruk 1967, 202). The surviving copies of Yudisher shtam have reached us in composite manuscripts[13] or as printed booklets, hailing from the German-speaking territories as well as northern Italy,[14] and spanning a period from the early sixteenth to early eighteenth centuries (Dreeßen 1971, 9-31). Philological research, however, suggests that the poem itself was composed as early as the fifteenth century (Staerk and Leitzmann 1923, 271), while cultural-historical contextualization points to earlier origins (Shmeruk 1967, 204).

The Melody Known as Niggun ‘Akedah

An inseparable part of the stanzaic structure of the ‘Akedah piyyutim is their designated melody, the above-mentioned Niggun ‘Akedah (‘Akedah melody). As will be demonstrated below, this melody became strongly associated with the narrative of the Binding of Isaac and was also used for additional songs in Hebrew and Yiddish, the content of which relates to the Bindingof Issac in various ways.

Ashkenazi Jews did not employ Western notation until the late eighteenth century and relied instead on oral transmission of their musical traditions.[15] The only implicit written records of Niggun ʽAkedah prior to the modern era are verbal mentions of the melody, and the contrafactum reference “Be-niggun ʽAkedah,” i.e. the Hebrew (or indeed Yiddish) statement that a certain text should be sung ʽto the ʽAkedah melody’. [16] Such remarks provide little information concerning the music itself, yet they offer valuable insights for the present study, as will be demonstrated below.

Since the late eighteenth century, a growing number of Jews within the Ashkenazi realm became proficient in Western music notation, enabling them to record Jewish liturgical melodies, first on separate music sheets and then in cantorial compendia (Goldberg 2002). We have located in these sources thirteen transcriptions of chants for ʽAkedah piyyutim recorded between 1840 and the Holocaust period. A close study of these melodies follows the discussion of verbal references.

Verbal References to the Niggun ‘Akedah

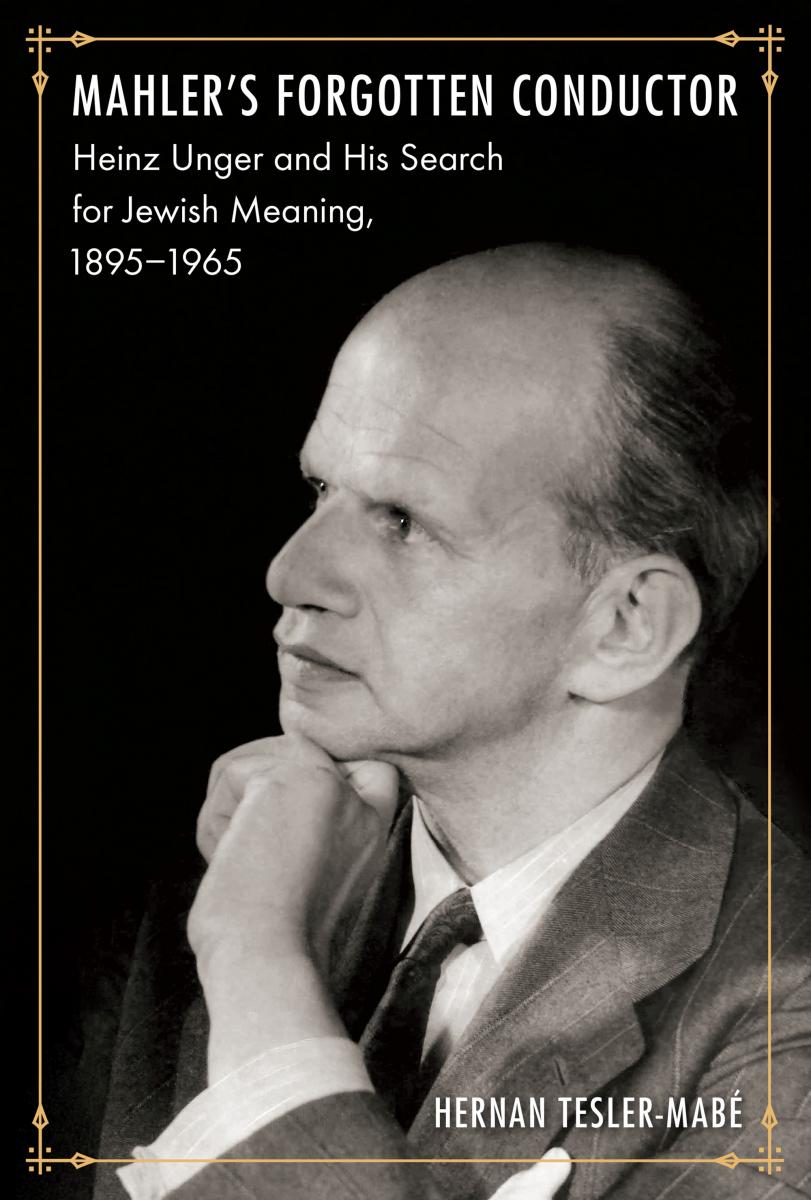

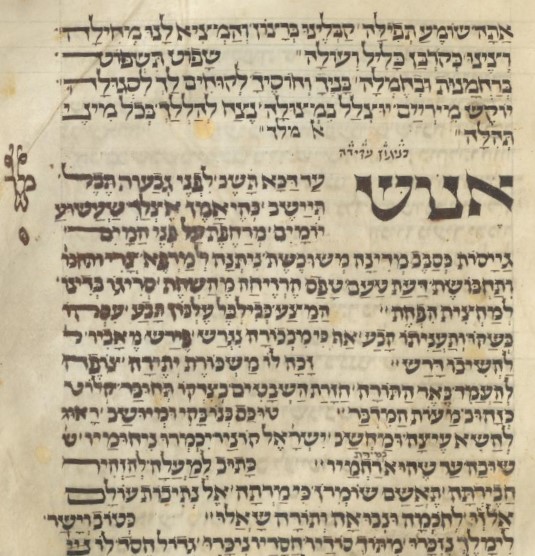

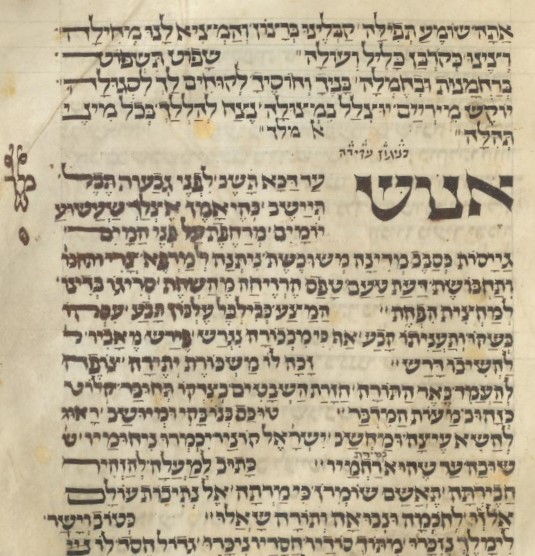

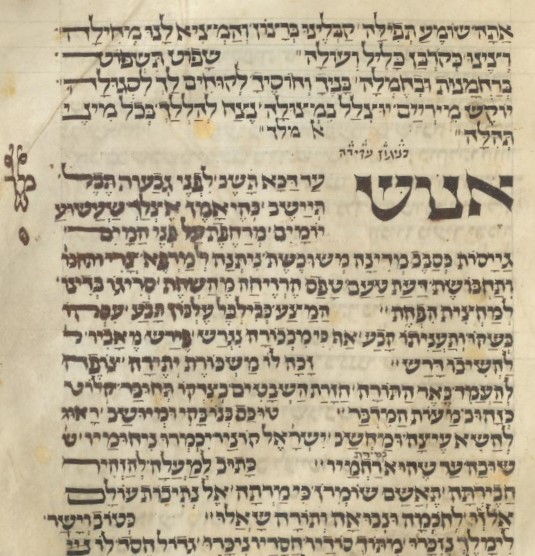

We have never come across the indication be-niggun ‘Akedah over an ‘Akedah piyyut. Apparently precentors were aware that such piyyutim were sung to this melody. The indication “Be-niggun ‘Akedah” appears, however, before songs which are not ‘Akedah piyyutim, but should yet be sung to this melody.[17] Such cases occur in various contexts in both Hebrew and Yiddish songs. Thus, a piyyut entitled ’Enosh ʽad daka tashev which appears in a fourteenth century Seliḥot anthology is preceded by the singing instruction Be-niggun ‘Akedah (Reuchlin 7, 63r. Fig 2). This poem is not an ‘Akedah piyyut, but rather a poem about repentance (teshuva); yet it was sung to the‘Akedah melody.

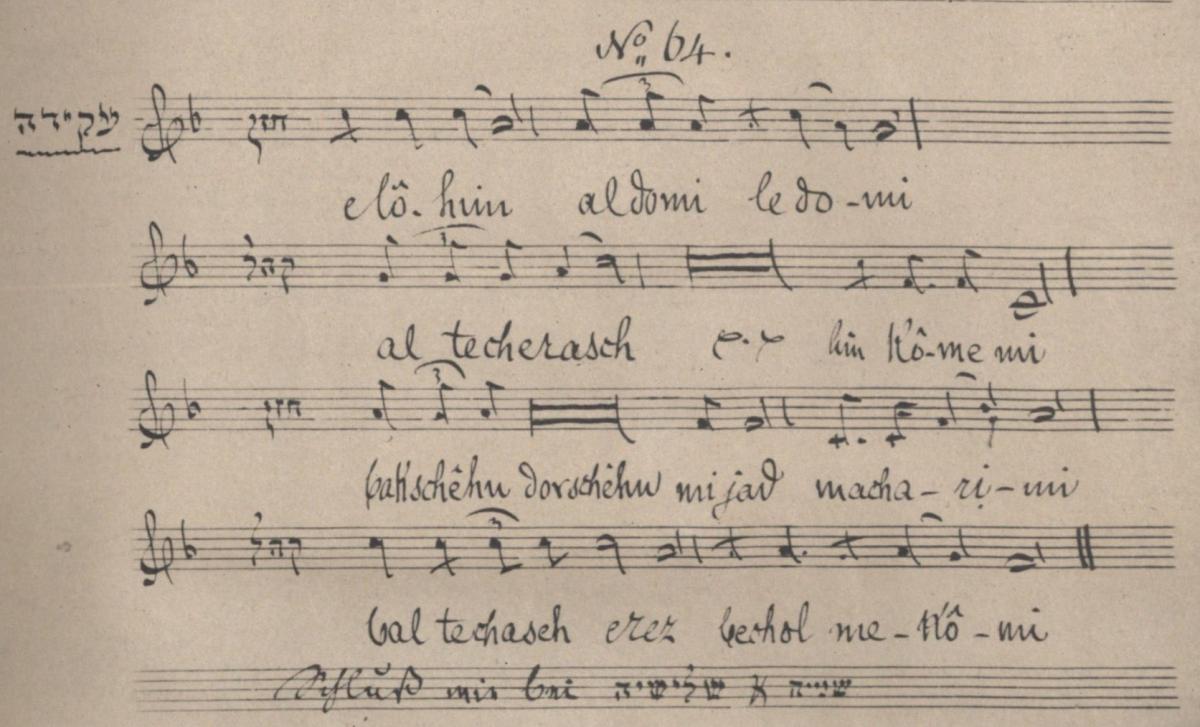

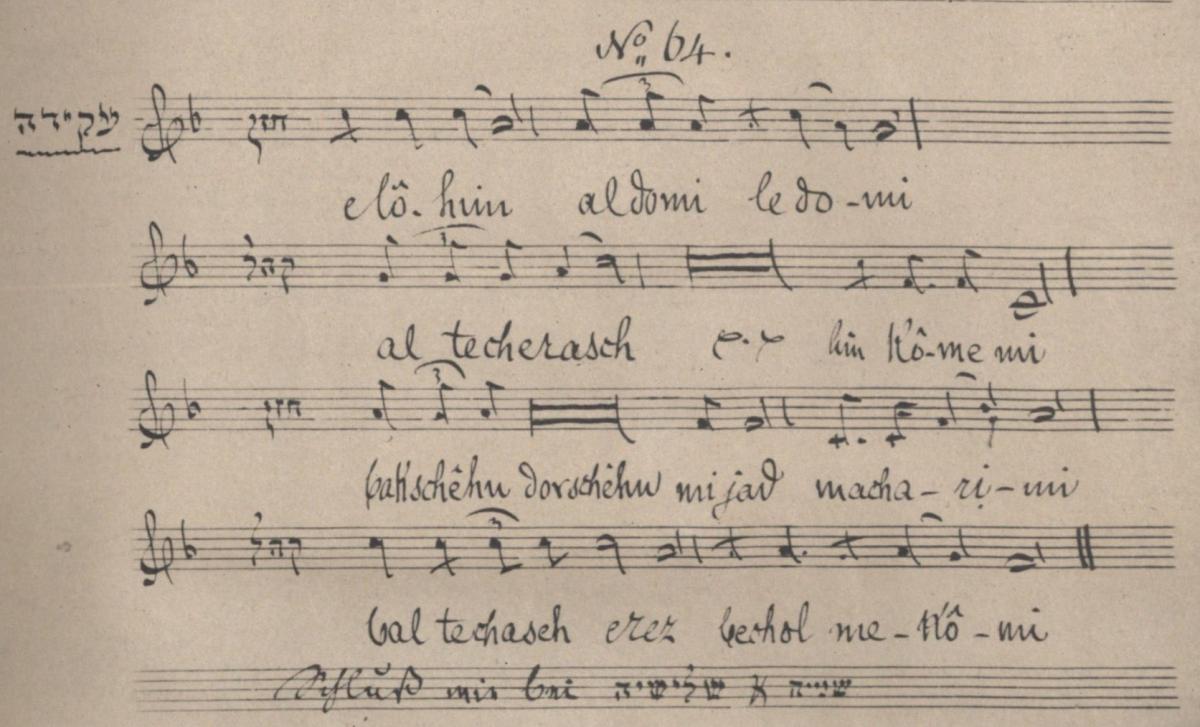

Figure 1: ‘Akedah Melody in Kohn 1870, 31 [No. 64], Mus Add 4 (a), Eduard Birnbaum Music Collection, Klau Library, Cincinnati, Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion

Another early example of such a musical instruction is found in the book of customs, Minhagei Maharil: “When a circumcision took place on a Fast Day, Maharil used to say Seliḥot, and one of them, ʽDo not break your covenant with us [O God]’, was set to the ‘Akedah melody” (Sefer Maharil, Hilkhot mila, siman 10; Schleifer, 2014). The piyyut mentioned here, whose subject is the circumcision as commanded by the Torah, is a Shalmonit piyyut, written in quatrains with the rhyming scheme aaax, bbbx, etc. Singing this piyyut to the ‘Akedah melody was apparently meant to draw a parallel between the circumcision of a newborn son and Abraham’s near sacrifice of Isaac.[18]

Within the corpus of early modern Yiddish literature, three seventeenth-century songs include an instruction that they should be sung “Be-niggun ʽAkedah”: The first is Eyn sheyn lid fun Vin, a historical song describing the deportation of the Viennese Jewish community in 1670 (Turniansky 1989; Steinschneider 1852–1860, 568, no. 3668). The song is written in monorhymed quatrains, but interestingly has a recurring refrain, a fifth line, independent of the stanza: ve’eykh ʼenaḥem (and how can I be consoled?). This refrain alludes to a lamentation of Ninth of Av,[19] conceivably because the imperial deportation edict was issued close to that date.

Figure 2: 'Enosh ʽad daka tashev' with the Indication Be-niggun ‘Akedah (Karlsruhe, Badische Landesbibliothek, Cod. Reuchlin 7, 63r)

The second song is Eyn nay lid gemakht bilshon tkhine, requesting God's protection from misfortunes such as sickness and untimely death, and more concretely from an ongoing plague epidemic which took place in Prague in 1680 (Steinschneider 1852–1860, 574, no. 3707; Kay 2004, 236–243). This song is in fact a prayer written in quatrains with a rhyming pattern aabb, ccdd, etc. Each line begins with the words foter kenig (O Father, King), referencing the Hebrew litany of the High Holy Day liturgy, ’avinu malkenu (Our Father and King; Steinsaltz 2000, 389). There are two known editions of this song.[20]

Lastly, Eyn sheyn lid oyf shney kedoshim […] is a historical song relating the story of two Jews from Prostits (German: Proßnitz; Czech: Prostějov) who were convicted of theft and sentenced to death, but withstood the temptation and/or coercion to convert to Christianity which would have earned them a pardon (Steinschneider 1852–1860, 572, no. 3692; Freimann 1923, 33, 46–53; Turniansky 1989, 44, 46). The song is written in quatrains with a rhyming pattern: aabb, ccdd, etc. Its singing instructions refer to either Niggun ‘Akedah or Niggun Brauneslid.[21] Interestingly, an Old Yiddish song from the early eighteenth centurybears the singing indication “Be-niggun prostitser kedoshim lid” (in the tune of ʽthe martyrs of Prostits’ song). [22] This later song relates the suffering of the Jewish community of Prague during a plague epidemic which took place in 1713 and is written in quatrains with the rhyming pattern aabb, ccdd, etc. Judging from its tragic content and formal structure, it appears that this song was sung to the tune of Niggun ‘Akedah, which had received a new name, probably due to the contemporary popularity of the songs (Freimann 1923, 33).

No extant copies of Yudisher shtam (including two seventeenth century pastiches of it)[23] contain any indication of its intended melody. This was apparently unnecessary, as in the case of ‘Akedah piyyutim, since it was obvious that one sings Yudisher shtam to the Niggun ‘Akedah. This assumption is accepted by most researchers of Yiddish literature (Zinberg 1943, 123; Erik 1928, 125–126; Shmeruk 1978, 118–119) and is strongly supported by the close thematic and structural similarities between the Hebrew and Yiddish poems.[24] And yet, the reference “Be-niggun Yudisher shtam” appears in Eyn sheyn nay lid, a seventeenth-century Yiddish song concerning the Ten Commandments (Steinschneider 1852–1860, 571, no. 3686), and may support the assumption that Yudisher shtam had its own melody, different than the Niggun ‘Akedah.[25] We understand this reference as a functional reflection of current popular acquaintance with different songs sharing the same melody, as was the case in the above-mentioned reference to Niggun ‘Akedah as “Niggun prostitser kedoshim”.

Finally, a most valuable verbal reference to Niggun ‘Akedah, albeit from the modern era, is found in Salomon Geiger’s book Divrei kehillot.[26] In this intricate work, which delineated meticulously the synagogue rite of the Frankfurt Jewish community in the nineteenth century (but lacking any musical transcriptions), Geiger explains:

‘Akedah – a Seliḥa [penitentiary piyyut] that speaks about those who died for the sake of Kiddush Hashem [sanctification of God’s Name] and about the Binding of Isaac, is called ‘Akedah. And it has a unique melody. And in the fourth line of its last stanza the melody differs from [the melody of] the fourth line of the opening stanza. (Geiger 1862, 129)

Later in his work, describing in detail the performance practice of the ‘Akedah piyyutim, Geiger notes that three such poems are chanted consecutively on the penitential service at dawn in the morning of Rosh Hashanah Eve.[27]He states that the first and third piyyutim are sung to the ‘Akedah melody, whereas the second one is sung to an ordinary melody of penitentiary piyyutim. Geiger wonders why the second ‘Akedah piyyut is not sung to the proper melody, assuming that: “Perhaps they [i.e. the cantors] did not want to sing three Seliḥot [penitentiary piyyutim] consecutively to the sad melody of the ‘Akedah” (Geiger 1862, 130).

The characterization of Niggun ‘Akedah as sad is crucial to the present study and will be discussed below in more detail. In his explanation, Geiger also broadens the definition of ‘Akedah piyyutim to which our melody is applied. He includes poems that describe Jewish martyrdom, and even ranks these first in his definition, before the poems portraying the Binding of Isaac. Indeed, among the ‘Akedah piyyutim which Geiger mentions are two dirges (Kinah piyyutim) for the Jews persecuted and martyred during the First Crusade. These poems—’Elohim ʽal domi ledami (Fraenkel, Gross, and Lehnardt 2016, 72–89; Haberman 1971, 69–71) and ’Et hakol kol Yaʽakov (Fraenkel, Gross, and Lehnardt 2016, 192–199, 476–477; Haberman 1971, 64–66)—are written in monorhymed quatrains, and draw parallels between the medieval case of Kiddush Hashem and the ‘Akedah story, employing the Hebrew root עקד. The inclusion of these poems in the corpus of ‘Akedah piyyutim once again reinforces the idea that in Ashkenazi Jewish consciousness the Binding of Isaac was culturally associated with the traumatic memory of the Crusades, in effect blurring the distinction between the literary genres of ‘Akedah piyyutim and Kinah piyyutim. Moreover, we have noticed that many other Ashkenazi Kinah piyyutim contain formal and thematic similarities to ‘Akedah piyyutim.[28] This suggests that certain Kinah piyyutim were previously also sung to Niggun ‘Akedah, which indeed imbued them with a melancholic tone.

On the basis of the above-mentioned verbal references to our melody, it is possible to conclude that, thematically, most of the texts examined are lachrymose and include direct mentions of the Binding of Isaac and/or the traumatic persecution of Jews during the Crusades. Alternatively, some texts exploit the melody's association with these two themes and ascribe it to other contexts (for example, the circumcision of a son, repentance on the High Holidays or specific cases of anti-Jewish persecution). Such dramatic themes required a similar musical expression, supporting Geiger’s description of the melody as sad.

From a formal perspective, the prominence of the four-line stanzaic structure (quatrain) is clear, as is the variety and instability with regard to the number of words and syllables among the lines of the text, even within the same stanza. The verbal information thus appears to indicate that our melody must be composed of four flexible musical phrases (for those ‘Akedah piyyutim not written in quatrains, two couplets or four single lines could easily be sung as a quatrain).[29] In order to serve the text properly, the melody of each line unfolds without fixed meter, in an elastic structure capable of accommodating a varying number of syllables, similar to psalmodic formulae (Flender 1992). Similar to psalmody, the last line of the poem would deviate from the regular melody, leading it towards the mode of the next prayer.[30]

The State of Musicological Research

Considering the importance of the Binding of Isaac in Jewish lore and its prominent role in Ashkenazi sacred poetry, the meagre research concerning the melody to which the ‘Akedah piyyutim were chanted is surprising. It appears that Abraham Zvi Idelsohn (1882–1938) was the first to address this topic, devoting few yet valuable remarks to this melody. Idelsohn (1929, 167) mentions the “‘Akedah-tune” as the seventh of eleven “Ashkenazic tunes for individual poetical texts,” claiming that some of them may date back to medieval times. He argues that this specific melody, which was in practice in his days, originated in the Middle Ages: “the tune was customary in the fourteenth century, and was referred to by Maharil as the ‘Akedah-tune, because it was used for all the poems with the same content and meter.” (Idelsohn 1929, 170).

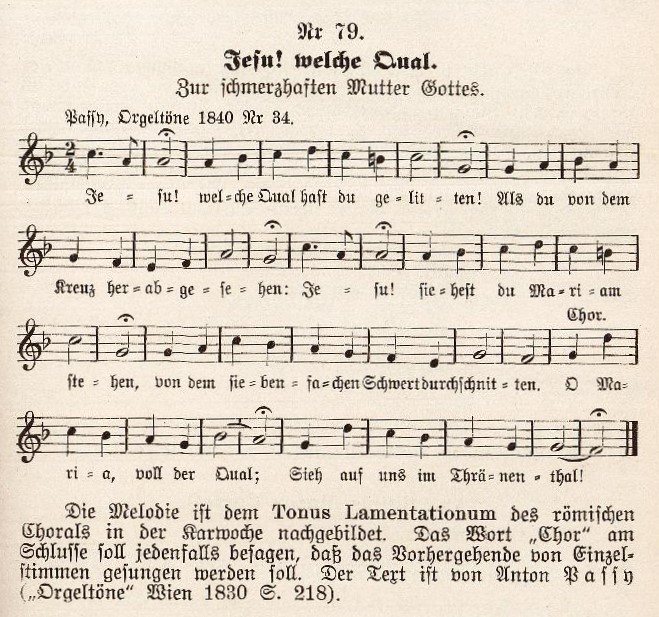

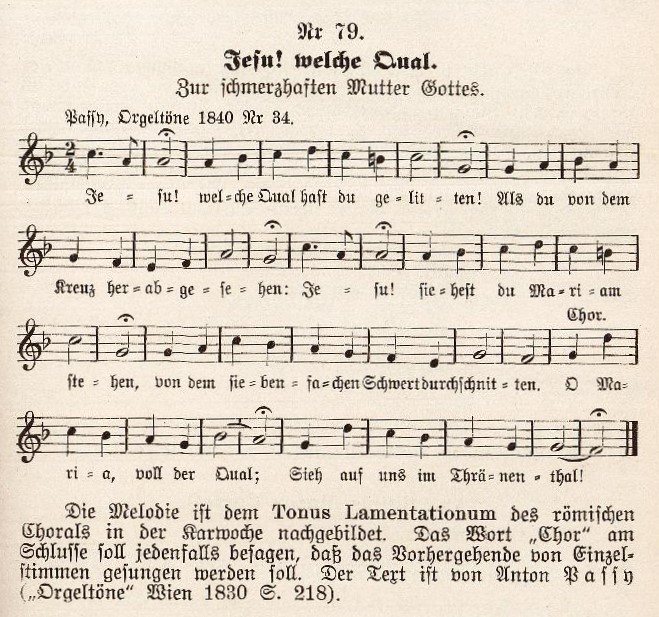

Figure 3: “Jesu, welche Qual hast du gelitten!” (Bäumker 1962 iv, 31 [No. 79])

Idelsohn provided no evidence to substantiate this claim, but three years later he returned to the subject in the seventh volume of Hebräisch-orientalischer Melodienschatz, dedicated to the synagogue chants of the Southern-German Jews (Idelsohn 1932). In a short comment that was probably meant to validate the melody’s antiquity, he compared the ‘Akedah melody (ex. 12), with that used for a late-medieval German song concerning Jesus’ suffering (fig. 3): “Eine ähnliche Weise ist die dem ʽTonus Lamentationum’ entnommene für den text ʽJesu, welche Qual hast du gelitten!’ (W. Bäumker, Bd. IV, Nr. 79)”—“A similar melody is the one based on [or borrowed from] the ʽTonus Lamentationum’ for the text ʽJesus, what agony you suffered!’”; (Idelsohn 1932, xlii).

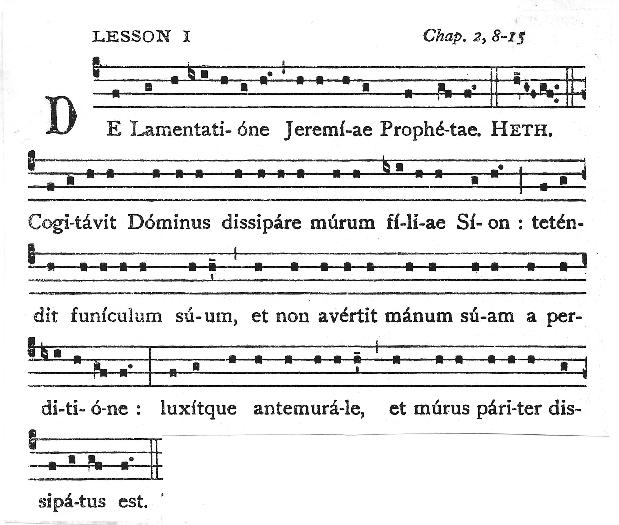

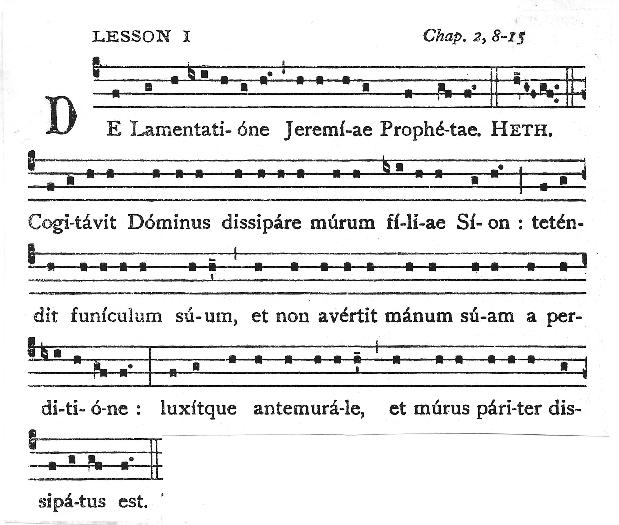

The “Tonus Lamentationum” is a psalmodic chant to which verses from the biblical Book of Lamentations are sung during the Divine Offices of Matins on the mornings of Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Saturday of the Holy Week before Easter (fig. 4; Liber Usualis 1961, 631–637; Schleifer 1980, 121–139).

Figure 4: Lesson I, Lamentations 2, 8 (Liber Usualis 1961, 692)

As the transcriptions above show, it seems that Idelsohn erred twice—once in relying on Bäumker’s statement that the German tune was based on the Catholic “Tonus Lamentationum”, and again in maintaining that the ‘Akedah melody was similar to the German song.

It is difficult to understand how this simple psalmody could have provided the melody for the German song “Jesu, welche Qual hast du gelitten!” which has a different contour, and whose modality belongs to a later development of the major mode. It is thus challenging to discern similarities between the German song and the ‘Akedah melody. At first glance it seems that both melodies share a general tendency towards the major mode (a matter we return to below) and that the first three notes of the German song resemble those of the ‘Akedah melody. Yet, the resemblance beyond this point appears rather dubious. Nevertheless, as we shall try to prove, it may be possible to corroborate Idelsohn’s claim concerning the melody's antiquity.

In 1963 musicologist Leo Levi dedicated a short article to surveying chants used for texts retelling the ‘Akedah in some Jewish communities (Levi 1963). Levi’s brief discussion of the Ashkenazi melody is apparently based on the above-mentioned observations by Idelsohn (1929). Like the latter, Levi agrees that the melody originates in the Middle Ages, and he mentions the possibility of its being based on some pentatonic foundations.

More recently, Diana Matut touched briefly upon the ‘Akedah melody in her discussion of a seventeenth-century parody of Yudisher shtam (2011 ii: 47–48, 200–201, 214). Referring to Idelsohn’s work, she excludes the possibility that his transcriptions (exx. 11 and 12) could represent the melody used for singing the parody. Matut claims that these transcriptions were intended for the Hebrew piyyut Tummat ẓurim, which has fewer syllables per line than the Yiddish song she examines (214). We cannot accept Matut’s claim because, as will be shown below, we regard the Niggun ‘Akedah as a non-metrical flexible melodic formula which could be adapted to a varying number varying number of syllables per line.

Geoffrey Goldberg’s new study of the piyyut Tummat ẓurim and its melody, as it appears in the cantorial compendia of Maier Levi of Esslingen (1818–1874; ex. 4), has made a major contribution to the research of the Niggun ‘Akedah. In his edition of Maier Levi’s music for the High Holy Days, Goldberg (2019, 109–111, 117; no. 29) provides a modern transcription of the melody and detailed annotations, including a list of comparable notated sources and a comprehensive liturgical and musical analysis of the Niggun ‘Akedah.

Transcriptions of the Niggun ‘Akedah

Having considered the current scholarship on Niggun ‘Akedah, we move to discuss the thirteen transcriptions of this melody in ascending chronological order.[31] All transcriptions belong to the Western Ashkenazi rite. In parallel, our search for recordings of ‘Akedah piyyutim at the National Sound Archives (NSA) at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem has yielded only one recording.[32] It is likely that this scarcity results from a combination of historical circumstances, and particularly the havoc that Nazi Germany unleashed upon Western Ashkenazi Jewry and its synagogue tradition.[33]

Cantor Michel Heymann, a faithful preserver of the Alsatian Jewish community’s chanting heritage (minhag Elsass) sings the one recording at the NSA.[34] While his singing in this recording is clear and accurate, it is also slightly hastened (given that he was asked to sing extensive parts of the High Holiday liturgy) and therefore difficult to rely upon for a meticulous transcription. Oren Roman visited Cantor Heymann in Luxembourg in September of 2017, on which occasion Cantor Heymann kindly agreed to sing the Niggun ‘Akedah. Two transcriptions from the recording made on that occasion are presented below as exx. 14a-b.

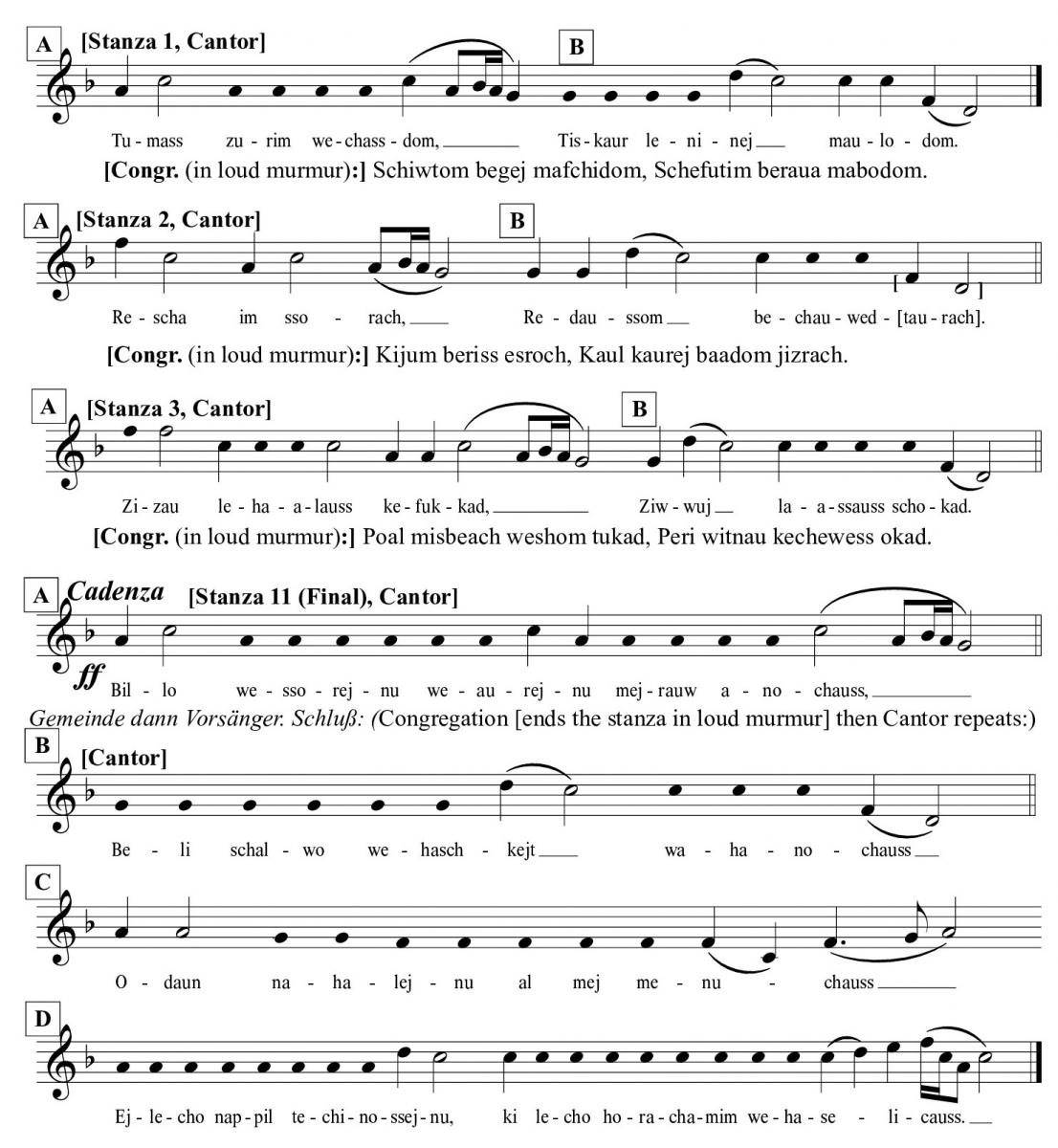

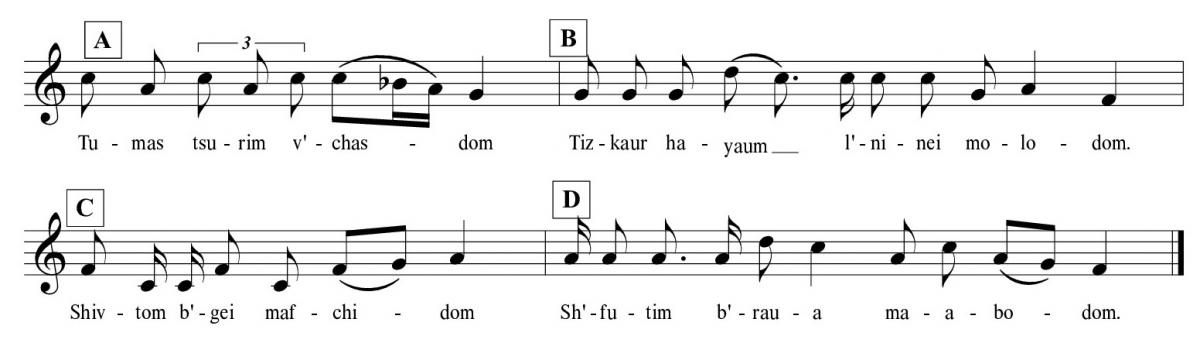

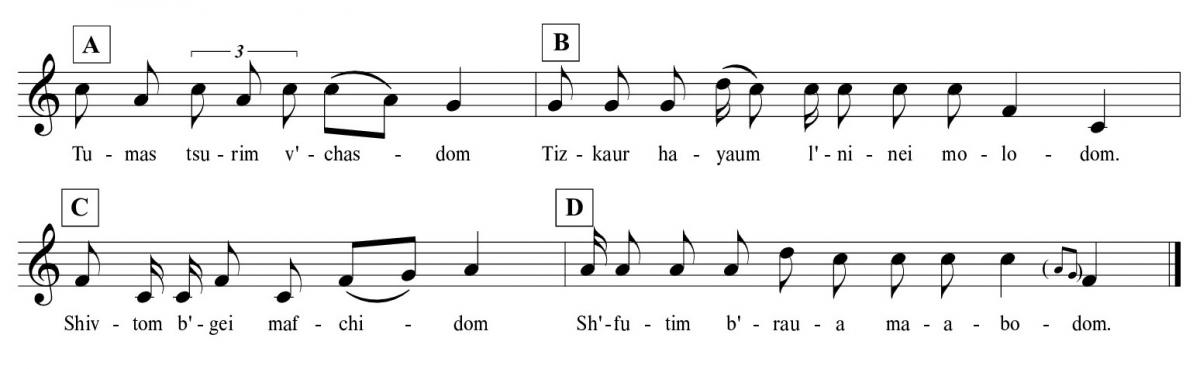

As we will demonstrate, all the extant musical sources employ the same four-phrase melody, with some variations. All versions are intended for alternating singing between cantor and congregation, or occasionally between cantor and choir.[35] In order to facilitate the comparison of the transcriptions, they are all presented in the uniform tonality of F (the original tonality is noted) with the letters A, B, C and D added to mark the four phrases that constitute the melody. Unless otherwise stated, the rhythmical values of the notes are presented exactly as they appear in each source, as are the texts’ titles, indications for singers and text-underlays. (To avoid confusion, the term “phrase” applies to music, while the term “line” to the text).

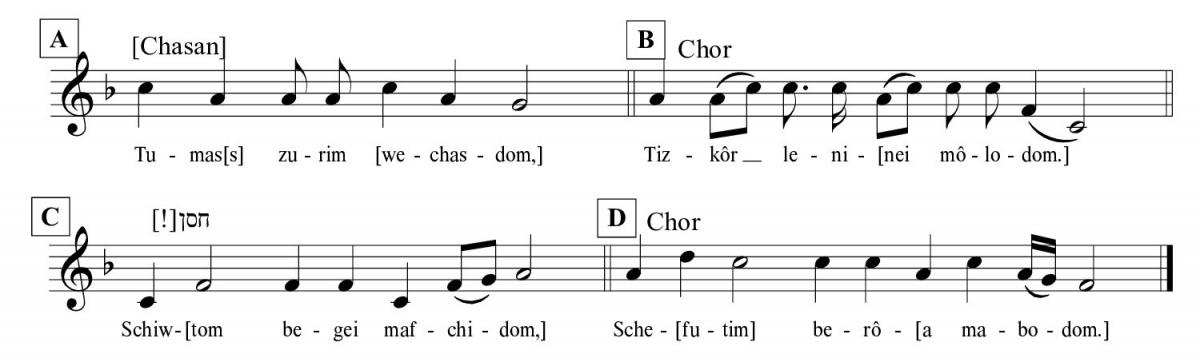

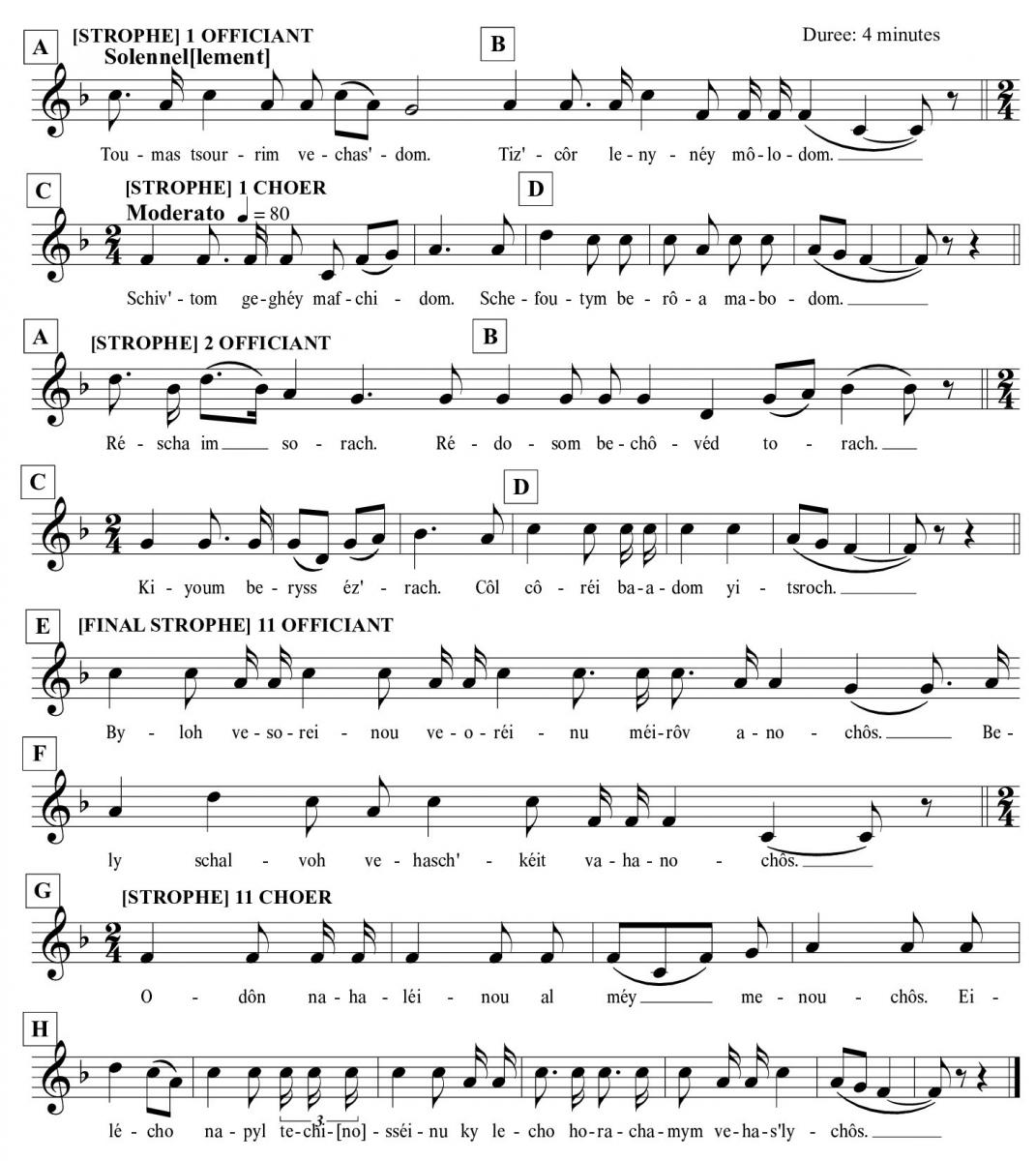

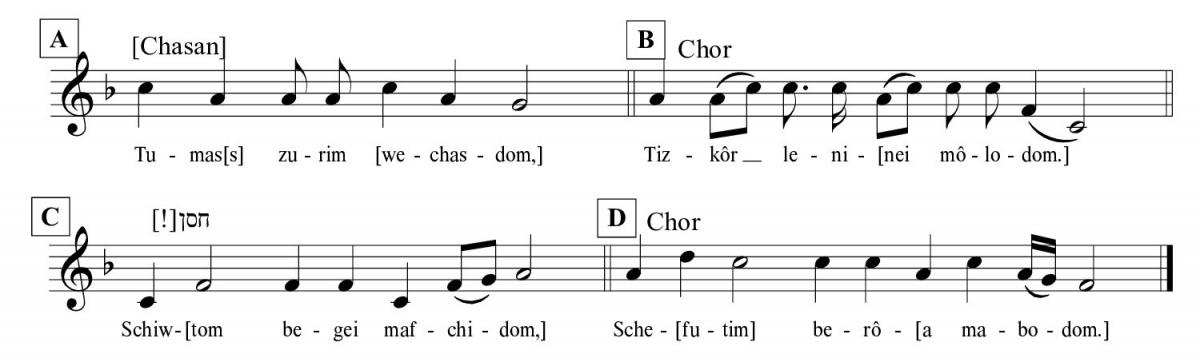

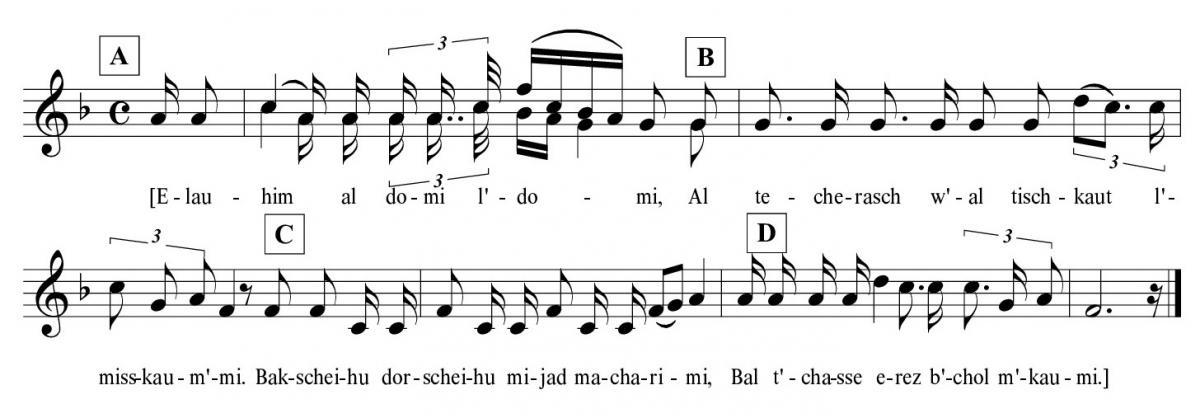

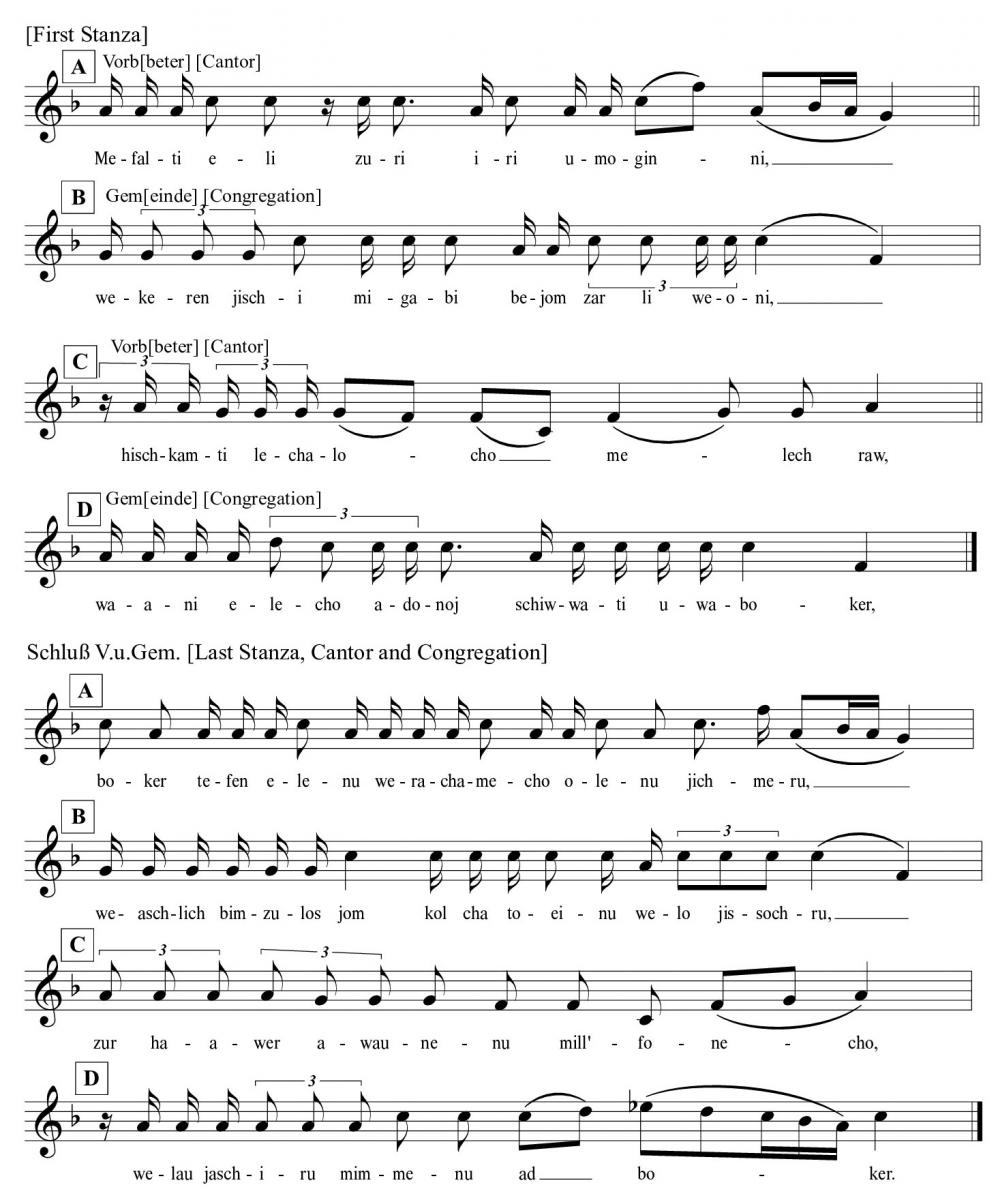

Example 1: Löw Sänger and Samuel Naumbourg (Munich 1840, 62–63)[36]

|

Original Title

|

תמת [sic]

|

|

Chosen Text

|

Tummat ẓurim.

|

|

Singing instructions

|

The first phrase (A) lacks an indication of the intended singer, but is understood to be the cantor's part. The third phrase (C) carries the title חסן (sic, cantor). The second and fourth phrases (B, D) are indicated as Chor (choir).

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

D, no fixed meter

|

|

Remarks

|

Only the melody for the first stanza is provided (no ending-version for the last stanza). The text underlay is very unclear, providing only the beginning of the lines. We reconstructed the remainder of the line (in square parentheses), according to the general style of the author.

|

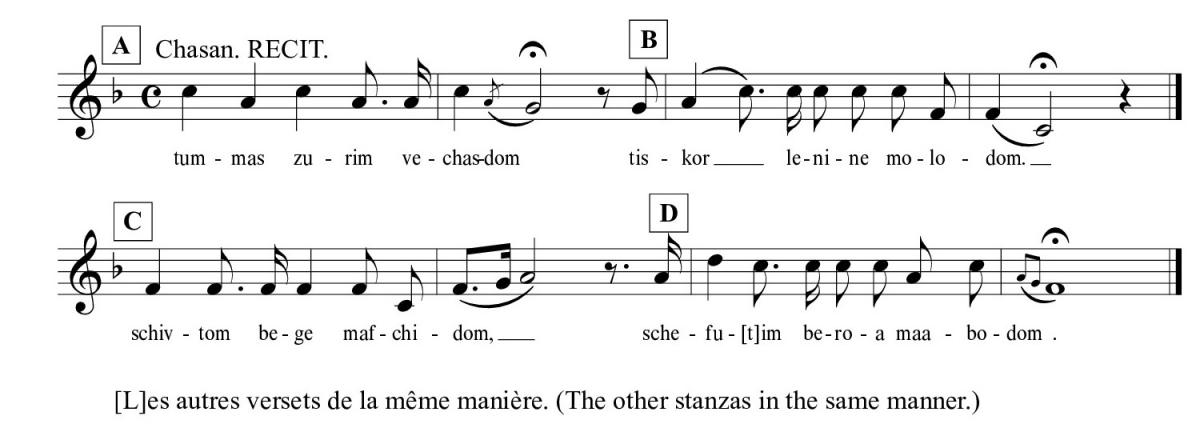

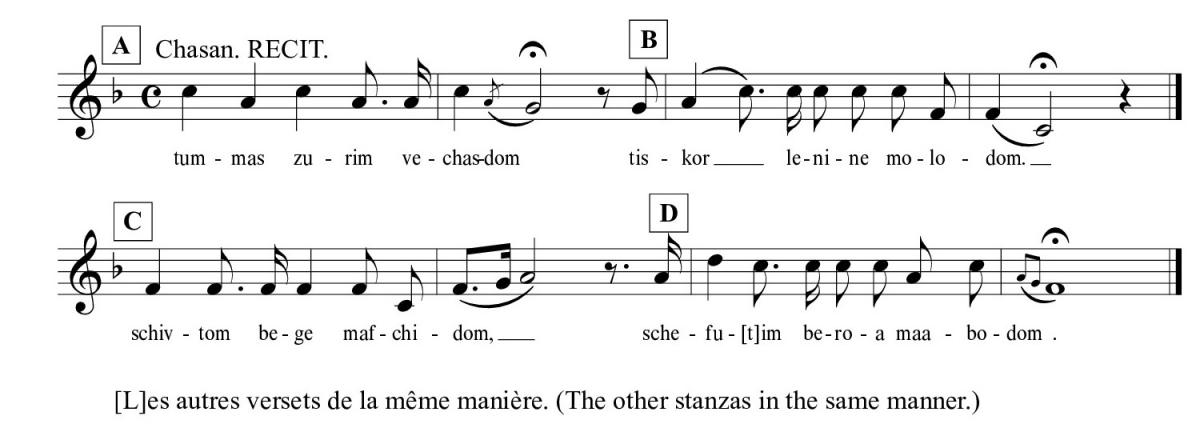

Example 2. Samuel Naumbourg (Paris 1847, 317 [No. 263])

|

Original Title

|

תמת צורים

|

|

Chosen Text

|

Tummat ẓurim

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

F, 4/4

|

|

Singing instructions

|

The beginning indicates Chasan (cantor) RECIT[ative]. At the end of the stanza, the indication reads: les autres versets de la même manière (the other stanzas in the same manner)

|

|

Remarks

|

Only the melody for the first stanza is provided (no ending-version for the last stanza).

|

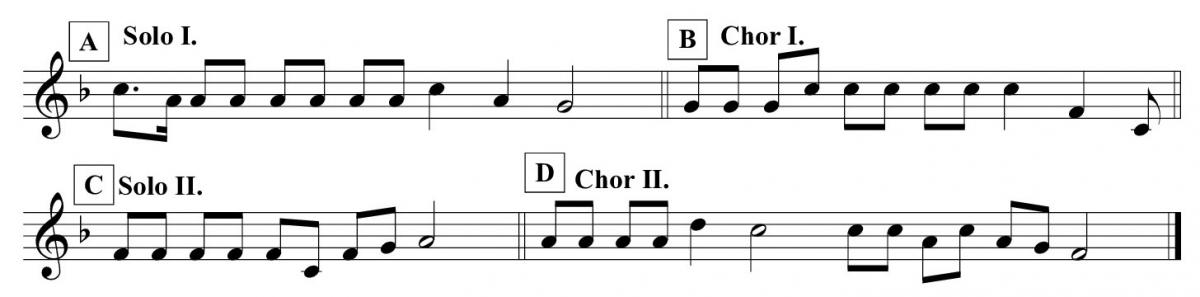

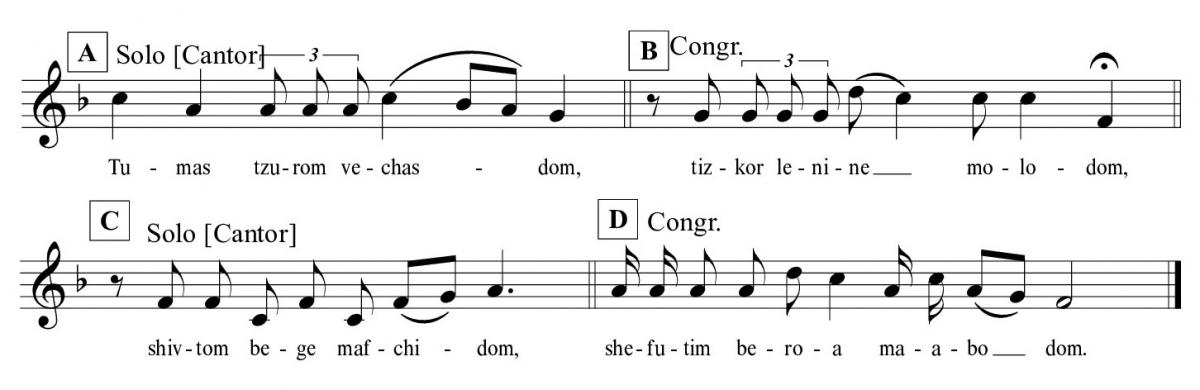

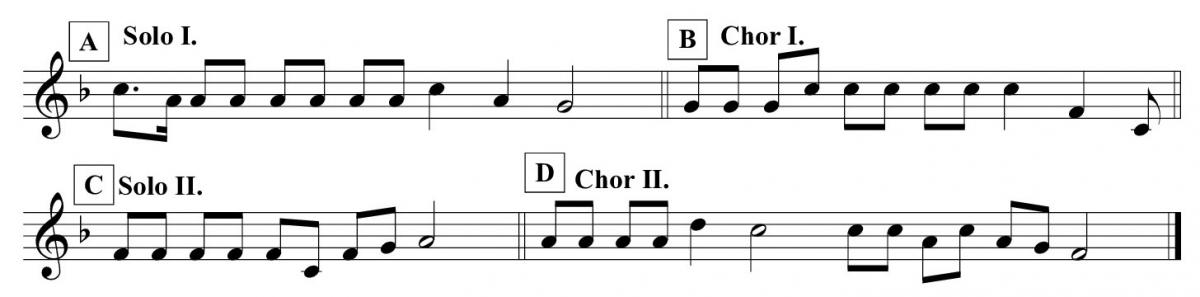

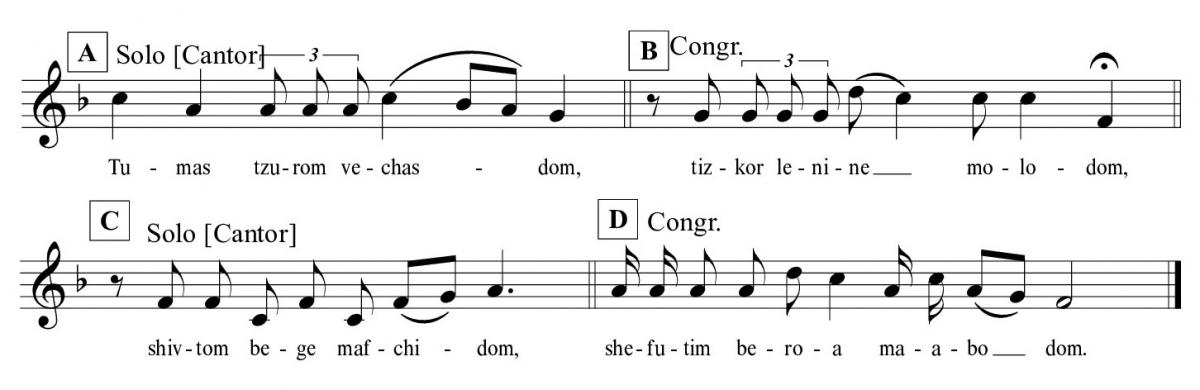

Example 3. Gerson Rosenstein (Hamburg 1852, 40 [No. 59a])

|

Original Title

|

עקידה, שנייה

|

|

Chosen Text

|

none

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

G, no fixed meter

|

|

Singing instructions

|

The four phrases of the melody are titled: Solo I [cantor’s first part]; Chor [choir’s first part] I; Solo II [cantor’s second part]; Chor II [choir’s second part]

|

|

Remarks

|

The melody is printed in a section described by the table of contents as, Anhang von Gebeten des ältern Ritus (Appendix of prayers of the older rite). As the Hebrew title indicates, the melody was intended for both ‘Akedah piyyutim, usually written in quatrains, and Sheniyyah piyyutim (another sub-genre of Seliḥot piyyutim, written in couplets). In the latter case, two consecutive couplets could be sung as a unit of four musical phrases with the ABCD form of the ‘Akedah melody.

|

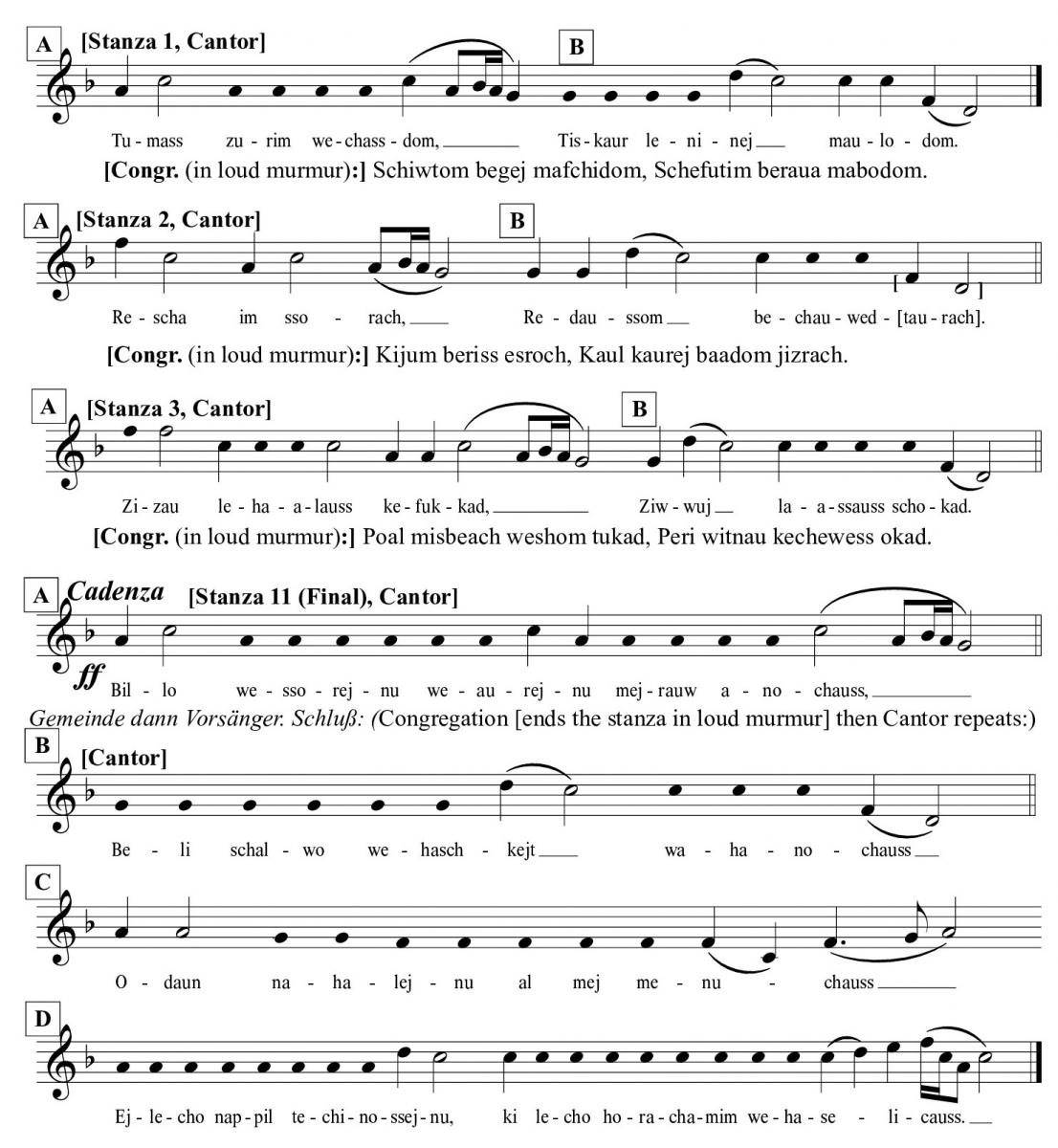

Example 4. Maier Levi (Esslingen 1862 ix, 86–91 [No. 30])[37]

|

Original Title

|

none

|

|

Chosen Text

|

Tummat ẓurim

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

D (stanzas 1-3); F (last stanza); all in no fixed meter

|

|

Singing instructions

|

For the first three stanzas, only the music of the first and second phrases is provided, including a text underlay written in large printed letters with the appropriate nikkud. The text of the third and fourth lines is penned in small cursive letters without nikkud or music. As this compendium was intended to serve the cantor, it seems probable that in this transcription the cantor sings the first two lines of the stanza (A and B), whereas the congregation recites the third and fourth lines (C and D), probably in the traditional Ashkenazi loud murmur.

Music is provided for all four lines of the last stanza, entitled Cadenza. After the second line, Levi comments: Gemeinde; dann Vorsänger. Schluß: (Congregation; then Cantor. End:), namely that the congregation should sing A and the cantor B–D.

|

|

Remarks

|

The musical transcription of this volume follows the writing direction of the Hebrew language. Volume IV was one of about a dozen (it remains unclear how many volumes existed originally) making up a vast cantorial compendium intended for teaching cantorial students. Geoffrey Goldberg (2000) provides an extensive study of Maier Levi’s life and work. An important discussion of the ‘Akedah melody in general and an analysis of Levi's melody including a comparison to other sources appears in Goldberg's edition of Levi’s chants for the High Holy Days (2019).

In the transcription of the last stanza, the dynamics sign given is ff (=fortissimo) and the melody is transposed upwards from D to F, enabling the cantor to end on an impressive strong high note leading into the recitation of ’El melekh yoshev. In our transcription, we have Latinized the text underlay according to the German transliteration of Hebrew, as was common in Levi’s time and as he himself did in his later volumes.

|

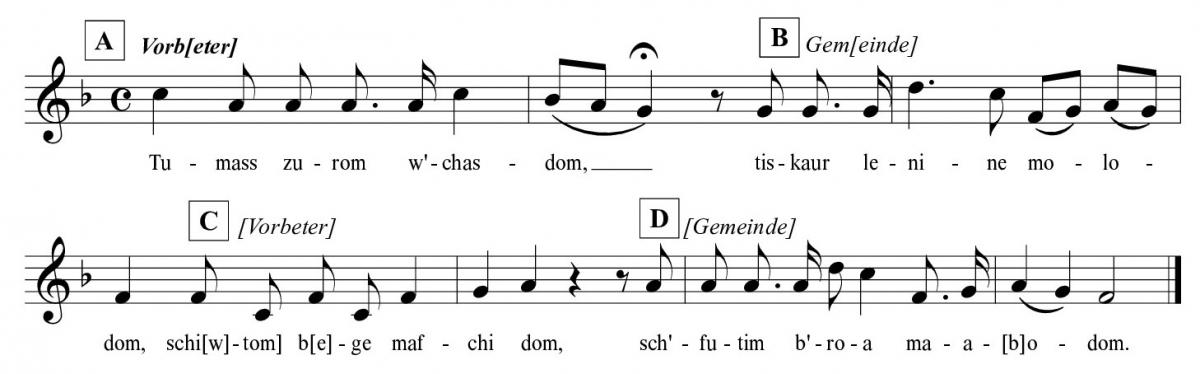

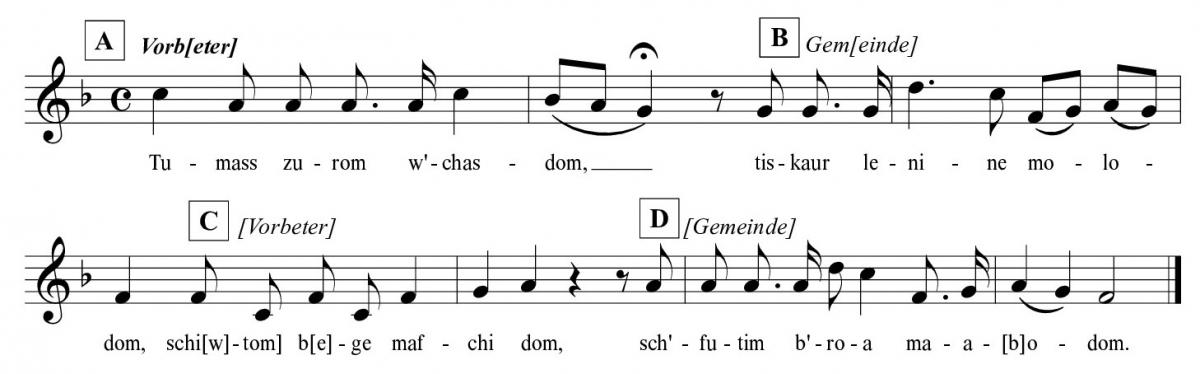

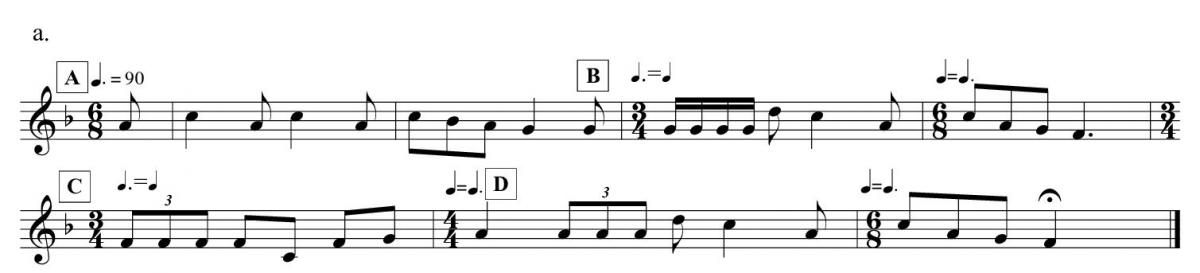

Example 5. N. H. Katz and Lazarus Waldbott (Brilon (Westphalia) 1868, 73–74)

|

Original Title

|

‘Akedah

|

|

Chosen Text

|

Tummat ẓurim

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

F, 4/4

|

|

Singing instructions

|

The word Vor[beter] (cantor) is inscribed over the beginning of musical phrase A and Gem[einde] (congregation) above the beginning of section B. As there are no further instructions, C and D were apparently to be sung by the congregation. There are no instructions regarding the ending-version of the last stanza.

General remarks: The melody for the first and second stanzas is provided (same for both), as well as an ending-version very different in musical character for the last stanza (indicated as Schlussstrophe [end stanza]). The latter (which is not given in the current example) bears no relationship to the ‘Akedah melody, but is based on the ending formulas for other piyyutim, such as sheniyyah and shelishiyyah.

|

|

Remarks

|

Katz and Waldbott force the melody to conform to common time; nevertheless, ignoring the artificial meter and bar lines, their version seems reliable. The text underlay is erroneous; we have taken the liberty of correcting it.

|

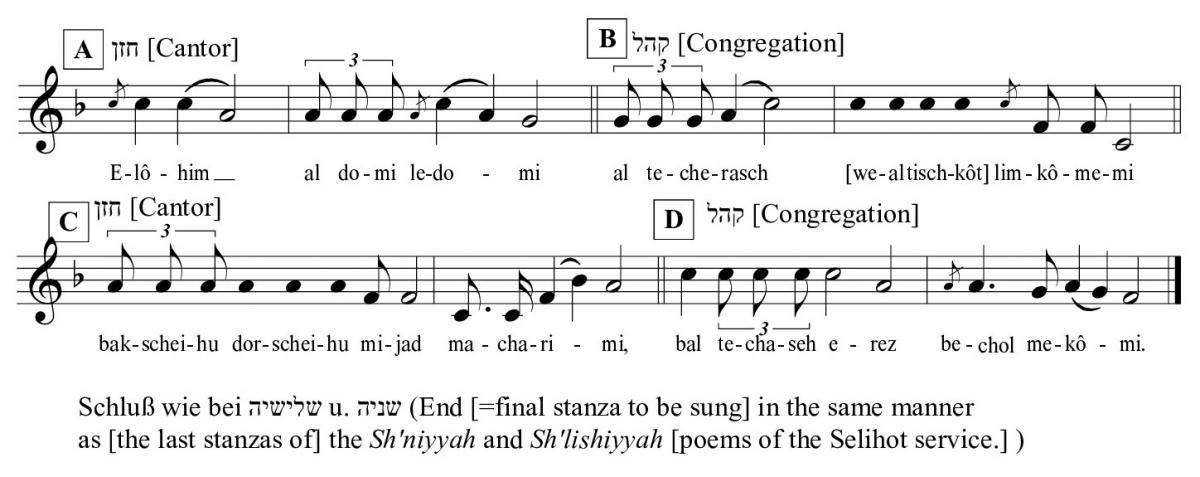

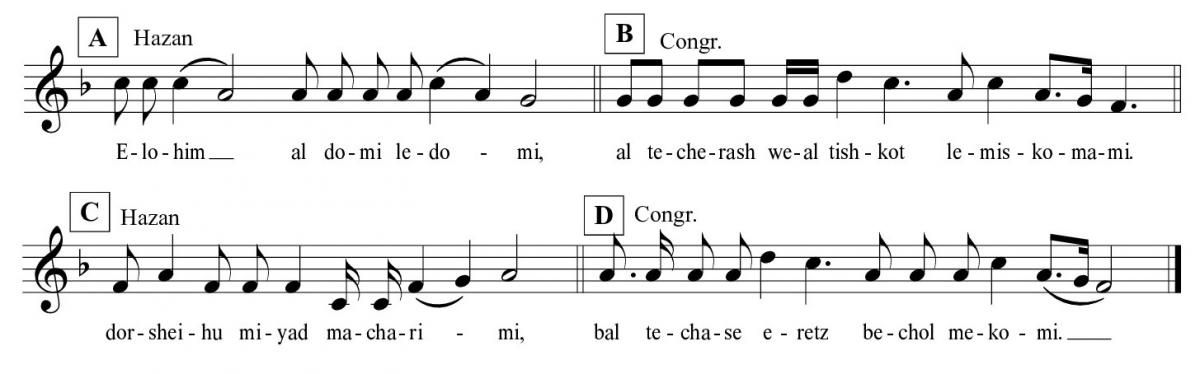

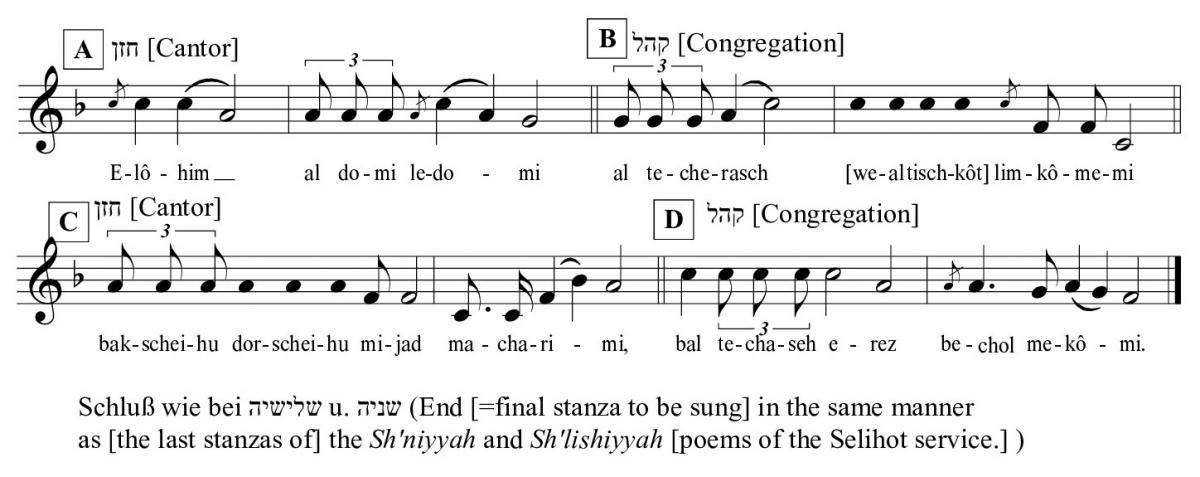

Example 6. Maier Kohn (Munich 1870, 31 [No. 64])

|

Original Title

|

עקידה

|

|

Chosen Text

|

ʼElohim ʼal domi ledami

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

F, no fixed meter

|

|

Singing instructions

|

A and C - חזן (cantor), B and D - קהל (congregation). Schluß wie bei שלישיה u[nd] שניה (the ending-stanza is to be sung in the same manner as the final stanzas of the Sheniyyah and Shelishiyyah piyyutim of the Seliḥot service.)

|

|

Remarks

|

Only the melody for the first stanza is provided (no ending-version for the last stanza has been notated, but a verbal explanation of it is provided). Each phrase is written on a different stave, with a vertical line drawn from the top to the middle of the stave, a caesura dividing the phrase into two segments. Some of the recitation tones are notated as breves, but in our transcription divides them into individual notes

|

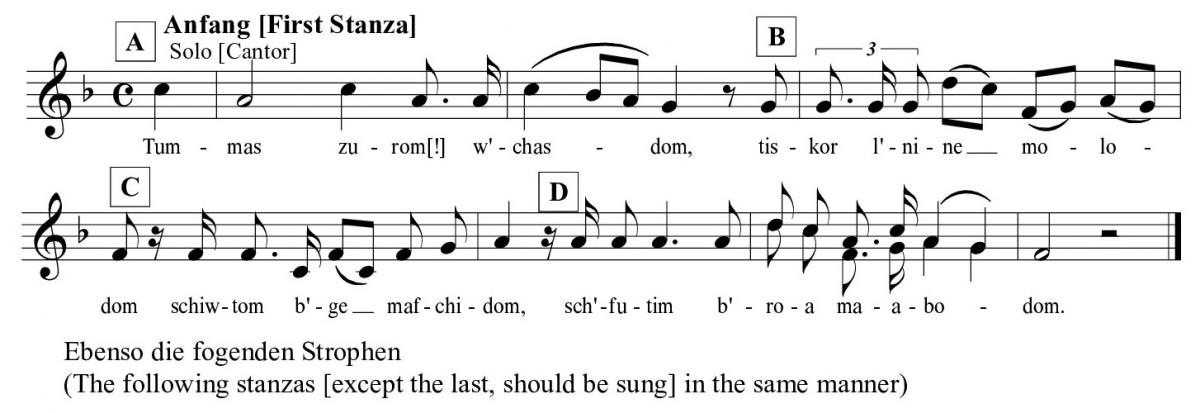

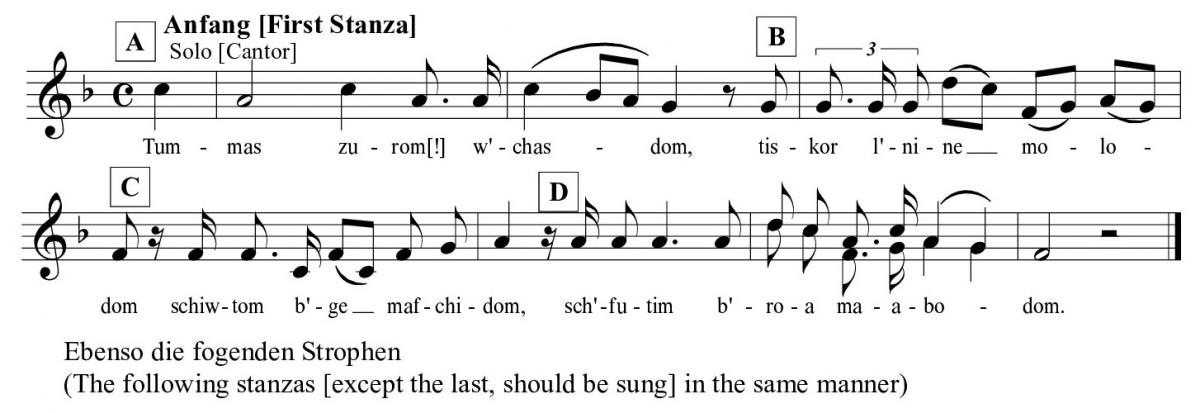

Example 7. Abraham Baer (Gothenburg 1882, 305 [No. 1320])

|

Original Title

|

תמת צורים (עקדה)

|

|

Chosen Text

|

Tummat ẓurim

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

F, 4/4

|

|

Singing instructions

|

The first stanza carries the performance indication Solo (cantor). This is followed by the indication Ebenso die folgenden Strophen, dann (similarly the following stanzas, then…) and the transcription of the last stanza, which is divided between Solo (cantor) for A and B, and Chor (choir) for C and D.

|

|

Remarks

|

The same melody is notated also on 322 [no. 1420]. The melody for the first stanza is provided under the title Anfang (beginning) and the melody for the last stanza under the title Schluss (ending). In our example we have omitted the transcription of the last stanza, the chant for which differs considerably from the ‘Akedah melody.

|

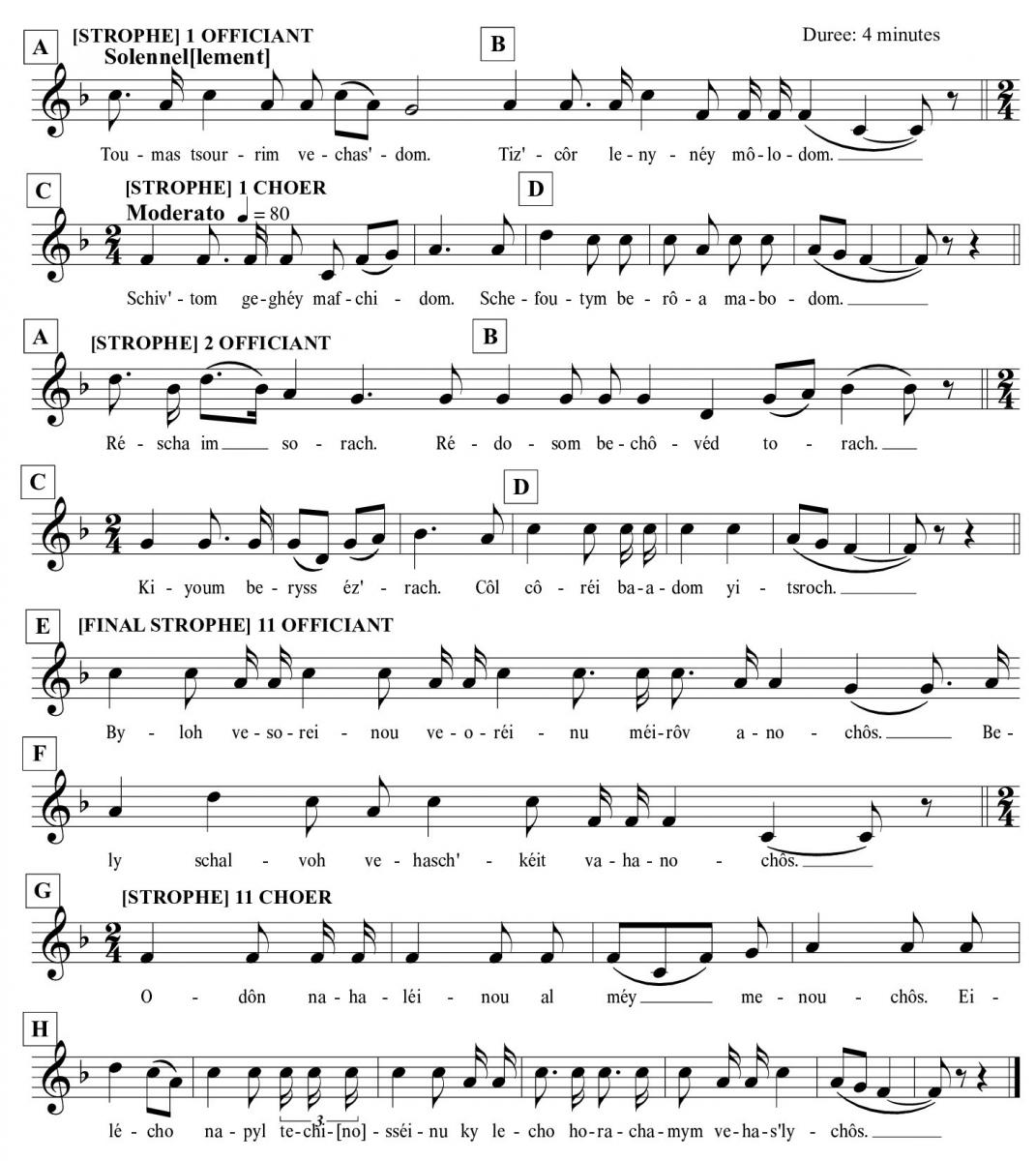

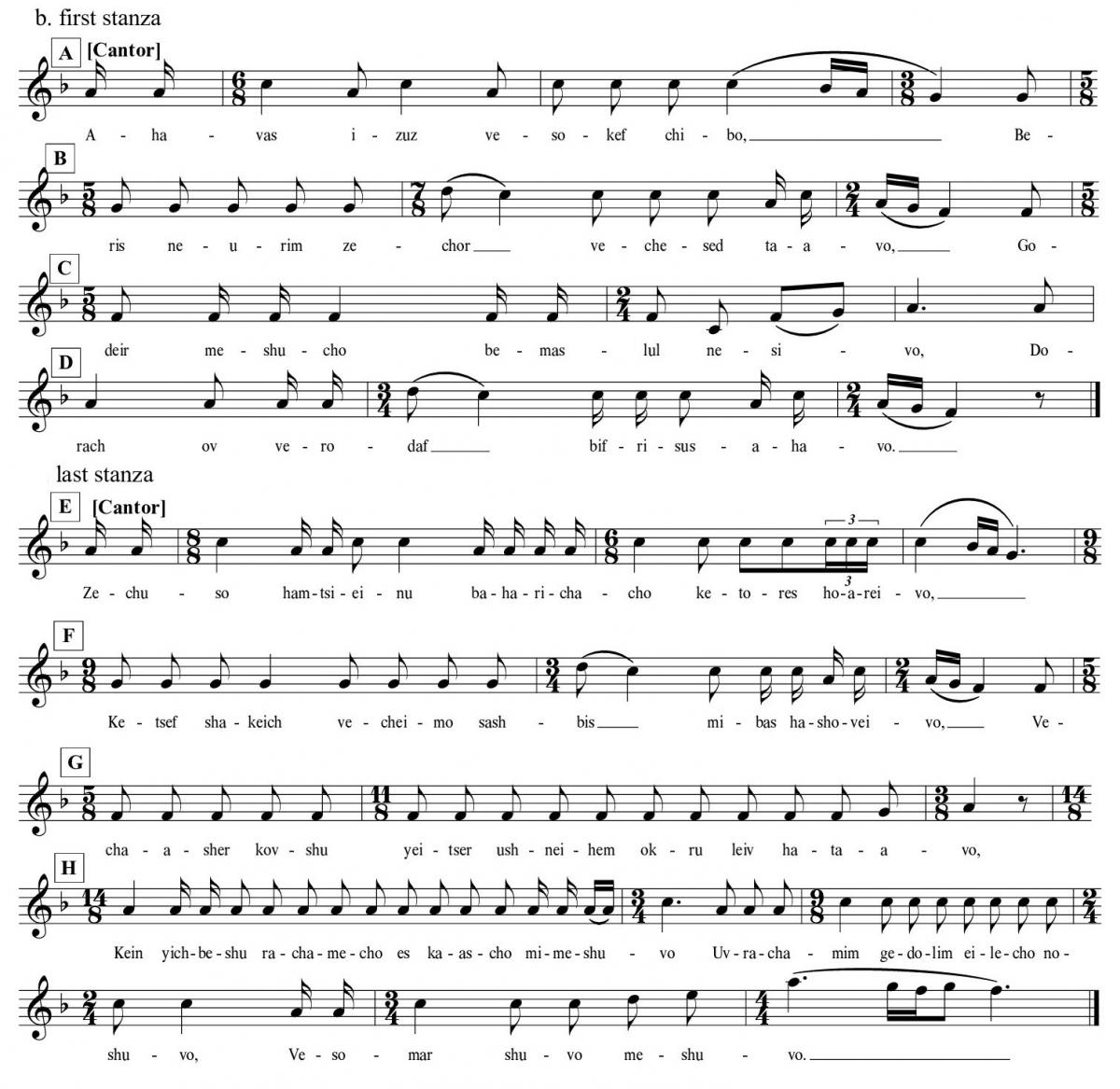

Example 8. Samuёl David (Paris 1895, 180–182 [no. 86])

|

Original Title

|

עקדה תמת צורים AKÉDAH/ TOUMAS TSOURIM/ Chant traditionnel dialogé/ KIPOUR

|

|

Chosen Text

|

Tummat ẓurim

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

F. The part of the Officiant (cantor) is in no fixed meter, marked Solennel[lement], (with solemnity), the part of the Choeur (choir) is in 2/4, marked Moderato, ♩=80. Duration is listed as 4 minutes

|

|

Singing instructions

|

The piyyut’s entire eleven stanzas are presented as a dialogue between cantor and choir: that the cantor sings the first two phrases (A and B) in free rhythm and solemn manner; whereas the choir sings the last two phrases (C and D) in strict 2/4 meter and moderately fast tempo. The singing instruction Officiant et Choeur complet à l’unisson (cantor and the entire choir in unison) seems to imply that this piyyut was not to be accompanied by the organ.

|

|

Remarks

|

In this rendition, Samuël David differentiates between the odd-numbered and the even-numbered stanzas. The odd-numbered stanzas portray the traditional Niggun ‘Akedah, whereas the even-numbered stanzas all bear the same clever modification of the original melody. The modern compositional technique and the fact that no such feature has been found in any of the other transcriptions of the ‘Akedah strongly suggest that the melody for the even-numbered stanzas was composed by Samuël David himself. In our reproduction of this transcription, we present the first two stanzas, which include both types of melodies.

|

Example 9. Fabian Ogutsch (Frankfurt 1930, 81 [no. 242])

|

Original Title

|

עקדה-Melodie

|

|

Chosen Text

|

none, probablyʼElohim ʼal domi ledami

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

C, 4/4

|

|

Singing instructions

|

none

|

|

Remarks

|

The transcription predates 1922, the year of Ogutsch’s death. While the transcription has no text underlay, the setting is syllabic: its individual notes, its beams and slurs, as well as its rhythms, fit the first stanza of ’Elohim ’al domi ledami. We therefore presented the melody with the text underlay of this poem. The common-time meter and the bar-lines are misleading and should be ignored. Ogutsch provides on p. 80, no. 236 the melody for סופי סליחות (Seliḥot endings).

|

Example 10. Abraham Zvi Idelsohn (Jewish Music, New York 1929, 167 [Table XXV, No. 7]

|

Original Title

|

none

|

|

Chosen Text

|

Tummat ẓurim

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

F, no fixed meter

|

|

Singing instructions

|

Solo (cantor) for A and C, Cong[regation] for B and D

|

|

Remarks

|

Only the melody for the first stanza is provided (no ending-version). Idelsohn discusses the “Akedah tune” in a short paragraph among his annotations for the Table XXV (p. 170), regarding it as a medieval melody (see below, State of Musicological Research).

|

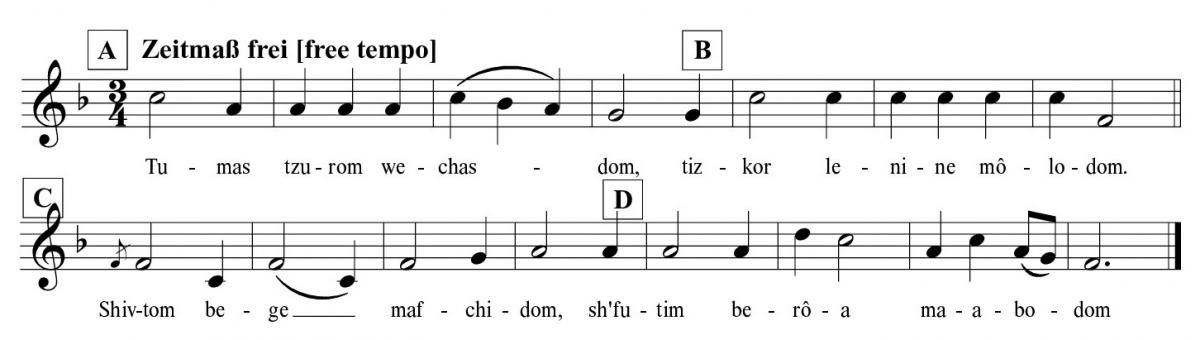

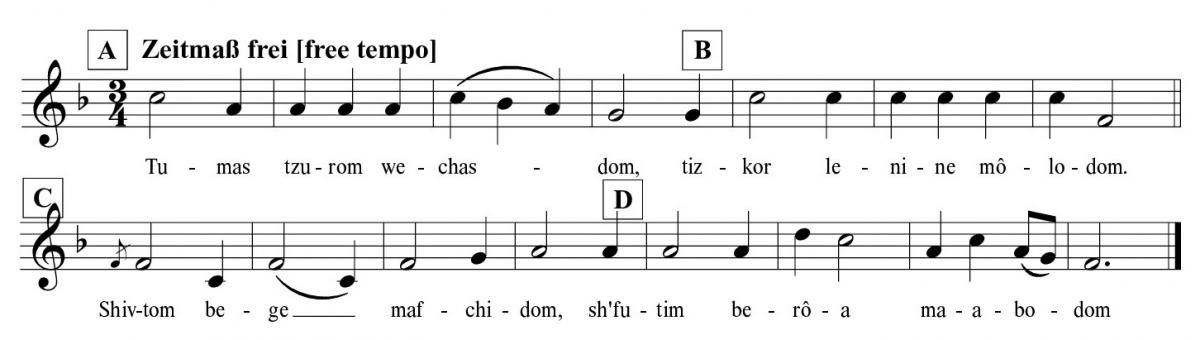

Example 11. Abraham Zvi Idelsohn (HOM, Leipzig 1932 vii, 108 [No. 312a])

|

Original Title

|

Akedoh

|

|

Chosen Text

|

Tummat ẓurim

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

F, 3/4 (the original indicates Zeitmaß frei, to be sung in free time)

|

|

Singing instructions

|

none

|

|

Remarks

|

Only the melody for the first stanza is provided (no ending-version for the last stanza).

|

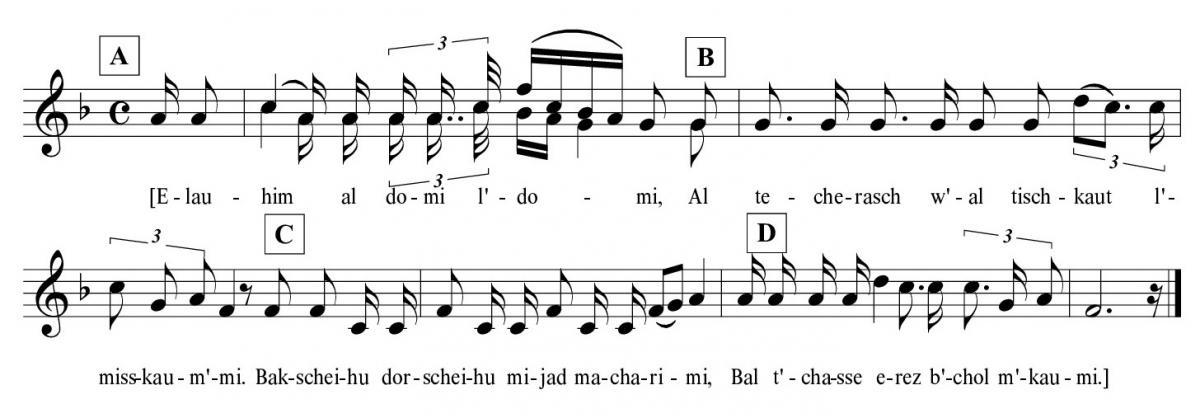

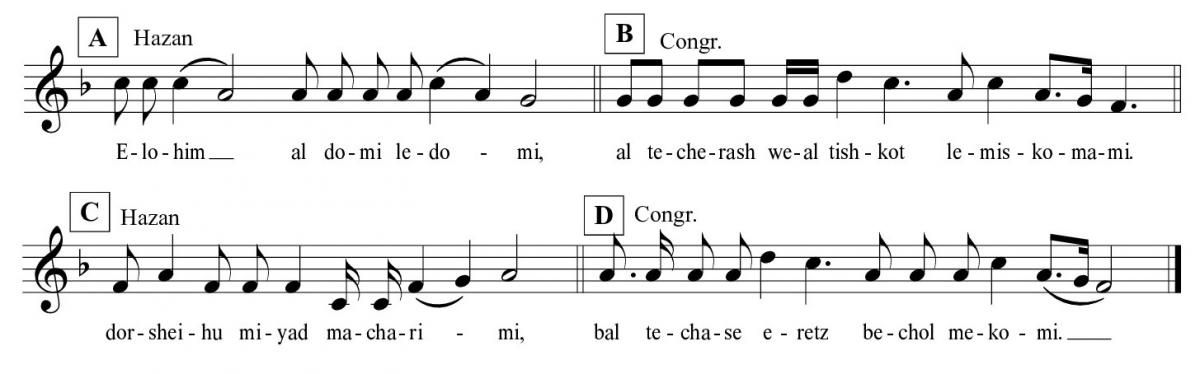

Example 12. Abraham Zvi Idelsohn (HOM, Leipzig 1932 vii, 93 [no. 256])

|

Original Title

|

Akedoh

|

|

Chosen Text

|

ʼElohim ʼal domi ledami

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

F, no fixed meter

|

|

Singing instructions

|

Hazan (cantor) for A and C, Cong[regation] for B and D

|

|

Remarks

|

Only the melody for the first stanza is provided (no ending-version for the last stanza).

|

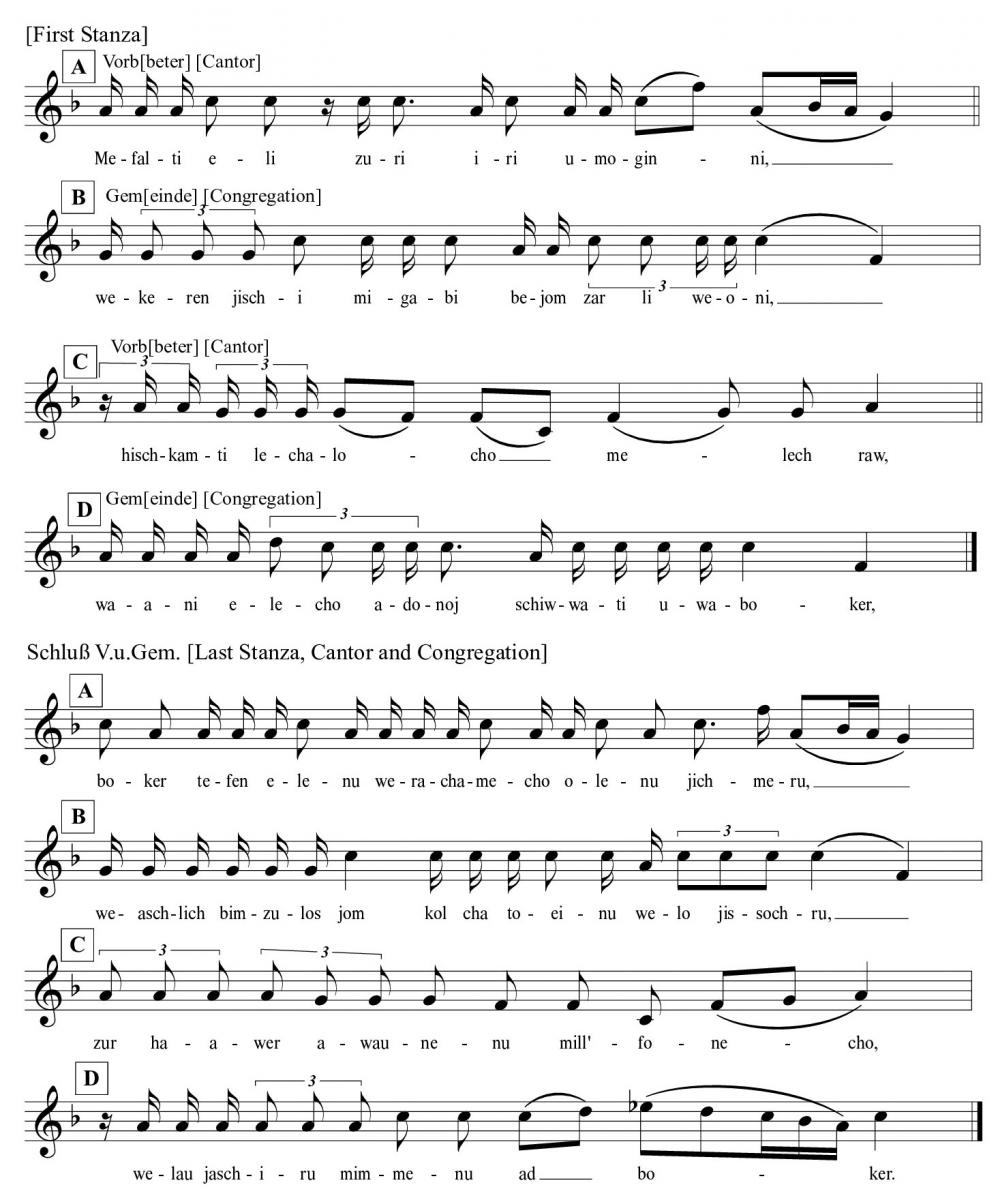

Example 13. Emanuel Kirschner (Munich 1932–1933, 40 [no. 76])

|

Original Title

|

Âkedoh

|

|

Chosen Text

|

Mefalti ʼeli ẓuri. An explanatory note attached to the end of the music reads: ʽEmmunim bene maʽaminim ebenso (likewise the piyyut ʽEmmunim bene maʽaminim)

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

C, no fixed meter

|

|

Singing instructions

|

For the first stanza, Kirschner indicates Vorb[eter] (cantor) for A and C, and Gem[einde] (congregation) for B and D. For the last stanza, he writes: Schluß [sic]. V[orbeter] u[nd] Gem[einde] (end. cantor and congregation)

|

|

Remarks

|

Kirschner provides the music for the first and last stanzas. The melody of the last phrase of the Schluss stanza is a transition to the next prayer.

|

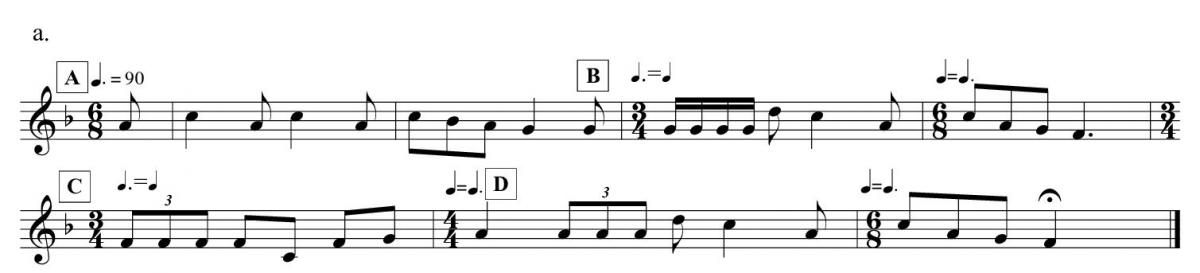

Example 14a. Michel Heymann (2017)

|

Original Title

|

ʽAkedah

|

|

Chosen Text

|

none

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

C, multiple meter, mostly in triple time patterns

|

|

Singing instructions

|

none

|

|

Remarks

|

Cantor Heymann sang just the melody without any text

|

Example 14b. Michel Heymann (2017)

|

Original Title

|

none

|

|

Chosen Text

|

’Ahavat izuz

|

|

Tonality and Meter

|

C, multiple meter, mostly in triple time patterns

|

|

Singing instructions

|

According to Cantor Heymann’s description during the recording, all stanzas except the final one are to be sung in alternation between the cantor (phrases A and B) and the congregation (phrases C and D). The entire last stanza is to be sung by the cantor alone.

|

|

Remarks

|

Cantor Heymann sang at a rather fast tempo, probably faster than in his synagogue rendition.

|

Analysis of the Transcriptions

Notwithstanding geographic and temporal differences, all the music examples are variants of the same melody. The melody itself presents a mixture of a folk tune and a psalmodic chant. It is simple, easily memorable, and repetitive, yet it recalls a psalmody, mainly due to recitation tones that render it flexible and enable it to accommodate a varying number of syllables. As will be discussed below, the documented ‘Akedah melody corresponds with the information gleaned from verbal descriptions of Niggun ‘Akedah. Combined with the clear and repeated similarities of the transcriptions, this undoubtedly indicates that the melody before us was the only one used for ‘Akedah piyyutim in the Western Ashkenazi rite during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and most likely prior to that. While it remains unclear how long before the first transcription this popular melody had circulated we will nevertheless suggest that some of its features situate it within medieval European musical culture.

Geo-Cultural Provenance

All the transcriptions belong to the Western Ashkenazi rite (minhag ’Ashkenaz); we have not discovered any Eastern Ashkenazi (minhag Polin and minhag Lita) transcriptions of the ‘Akedah melody (Goldschmidt 1965a, 6-8). Moreover, the transcription in Baer’s book (ex. 7) appears on a page divided into two columns: the right column is entitled Minhag Aschk’nas (i.e. Western Ashkenazi rite) and contains the piyyut Tummat ẓurim with the ‘Akedah melody, whereas the left column is entitled Minhag Polen (i.e. Eastern Ashkenazi rite) and contains the piyyut ’Omnam ken with a different melody. This clearly indicates that neither the text nor the melody was sung in the Eastern European rite.[38]

We tend to attribute the absence of the melody in Eastern European traditions to the simplistic manner of Seliḥot chants in that region. Unlike the musical system of the Western Ashkenazi rite, which could boast unique melodies for various kinds of piyyutim (not only ‘Akedah; Geiger 1862, 128–130; Idelsohn 1932, 93 [nos. 254-256]), in the Eastern Ashkenazi rite it was customary to sing ‘Akedah piyyutim in the same manner as other types of Seliḥot piyyutim. The cantor would sing the beginning of an ‘Akedah piyyut with a simple psalmodic phrase in the minor mode, then cantor and congregation would recite the remainder of the piyyut silently or in an audible murmur. Finally, the cantor would sing the last stanza in the major mode while transitioning to the following prayer, which in most cases leads to the recitation of the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy (Geshuri 1964, 224–225; Spiro 1999, 27 [no. 6], 30–31 [nos. 9–10]).

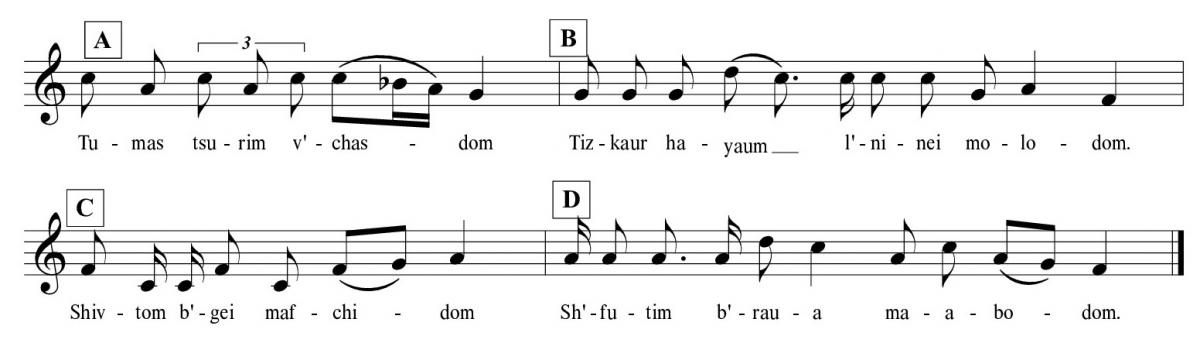

Choice of Poetical Texts

The selection of specific piyyutim for the various transcriptions of Niggun ‘Akedah (and the one recording) appears to demonstrate the prominence of certain poems over others, at least at the time when these transcriptions were made. The most popular piyyut was undoubtedly Tummat ẓurim,[39] which was used in eight cases (exx. 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, and 11) as the model text to accompany the transcription. Clearly, the reason for this overwhelming popularity is the setting of Tummat ẓurim in the Yom Kippur evening service: it is the first ‘Akedah piyyut recited on the holy day (Goldschmidt 1970, 32; Heidenheim 1892, 91–93). Ex. 13 uses the piyyut Mefalti ’eli tzuri (Goldschmidt 1965b, 101 [no. 39]) which is recited on the morning of Rosh Hashanah Eve and is in fact the first occasion during the High-Holiday season on which an ‘Akedah piyyut is said (Goldschmidt 1965b, 1970, 1993). Ex. 14b uses the piyyut ’Ahavat izuz which is recited during the Yom Kippur musaf service, a most meaningful service for the expert Ḥazzan. Exx. 6, 9, and 12 use the text of ’Elohim ’al domi le-dami, which is also considered a Kinah piyyut (dirge), describing and bewailing Jewish martyrdom during the First Crusade. In Western Ashkenazi practice, this dirge is also recited during the Yom Kippur musaf service. Composed by David bar Meshulam, who personally endured the calamities he describes, this is perhaps the earliest piyyut portraying the persecution of the Jewish communities in the Rhineland in 1096. It is also considered the first piyyut to draw a connection between the Jewish acts of martyrdom (Kiddush Hashem) and the ‘Akedaht Yizhak narrative; as such it influenced later similar texts, especially within the genre of ‘Akedah piyyutim (Fraenkel, Gross, and Lehnardt 2016, 72-73, 477-479). Ex. 13 mentions ’Emmunim benei ma’aminim, an ‘Akedah piyyut usually said in the morning service of Yom Kippur (Goldschmidt 1970 ii: 228).

Interestingly, Gerson Rosenstein (ex. 3) and Abraham Baer (ex. 7) mention that the ‘Akedah melody suits also Sheniyyah piyyutim (a different sub-genre of the Selihot piyyutim, written in rhyming couplets; Weinberger 1998, 223, 263-267, 318–319; Goldschmidt 1965b, 9). Baer specifically mentions the Sheniyyah piyyut’Ana’ ha-shem ha-nikhbad ve-ha-nora’. In such case, two couplets are sung in tandem as a quatrain.

Ending-Version (Schluss) and the Musical Framework of the Service

Consistent with Salomon Geiger’s comments above, some of the transcriptions conclude the recitation of an ‘Akedah piyyut with a special ending-version, often marked Schluss (end) for the last stanza. Exx. 4, 13, and 14 use the ‘Akedah melody at the beginning of the last stanza, but digress from it at the end; we have reproduced these ending versions in our transcriptions. Exx. 5 and 7 provide a different melody, not reproduced here, which is based on the conventional endings of the Seliḥot prayers. Ex. 6 does not provide an ending melody, but advises the cantor to sing it in the same manner as the last stanzas of the Sheniyyah and Shelishiyyah piyyutim.

It is our understanding that all the endings, both those that quote the Niggun ‘Akedah and those that do not, represent the wider musical-liturgical context of the prayer cycle of the Seliḥot service. They are designed to modulate from the mode of the ‘Akedah melody to the mode of the following prayer. In some cases, the transitional melodic line is developed into a bravura on high notes. The following prayer is for the most part ’El melekh yoshev ʽal kise’ raḥamim (God, the King who sits on a throne of mercy), the preface to the recitation of the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy, and this musical modulation serves as a cue for the congregation to physically rise.[40] The same phenomenon occurs in other similar cases, such as the endings of the melodies for Sheniyyah piyyutim, Shelishiyyah piyyutim, Shalmonit piyyutim, etc. (Geiger 1862, 129–130; Ogutsch 1930, 80 [no. 236]).

As this paper focuses on the Niggun ‘Akedah itself, our analysis pertains only to the melody of the regular verses, which is usually represented in the transcriptions by the first phrase. We do not address the ending-versions which, as a rule, are not characteristic of the ‘Akedah melody. An exception to this was made in the case of Maier Levi Esslingen’s transcription (ex. 4): the ending-version here is the only source for the third and fourth phrases. These phrases are similar to their parallel phrases in other transcriptions, and therefore have been included in our research.

Performance Practice

Twelve sources (all apart from exx. 9 and 11) provide some kind of singing instructions that is the designation of which melodic phrases are to be sung by cantor, congregation or choir. Additionally, some of the sources provide instructions regarding the singing of specific stanzas within the piyyutim. These performance guidelines often bear the imprint of their contemporary reality, and do not necessarily reflect the historical circumstances in which the melody was composed and chanted.

Thus, for example, indications of the choir’s role (exx. 1, 3, 7, and 8) serve as a clear testimony to the modern phenomenon of choral accompaniment in Western European synagogues, the setting in which the transcriptions were made. This phenomenon began with Solomon Sultzer’s modernization of Jewish liturgical music toward the third decade of the nineteenth century, and remained popular until the Second World War (Schleifer 1996). Yet it appears that some transcribers employed the indication ʽchoir’ for sections that are to be sung by both choir and congregation, in which case the choir led the congregational singing. This can be inferred from the simple melodic line found in the choir’s part, or as evidenced by a clear instruction in the preface to Abraham Baer’s cantorial compendium: “The heading ʽchoir’ is equivalent to ʽcongregation’.” (Baer 1882, ix). The modern concept of choir accompaniment, thus, may in fact have referred to the traditional congregational singing.

A different but similar type of instruction refers to responsorial singing. Most of the singing instructions indicate that the ‘Akedah piyyutim were sung in the synagogue in an alternating responsorial singing between cantor and congregation (or cantor and choir). Indeed, many maḥzorim include similar instructions for responsorial singing of the ‘Akedah piyyutim (Mahzor Sulzbach 1826, 35; Mahzor Amsterdam 1828, 140b; Heidenheim 1892, 91–93), but we chose not to explore this vast source of information regarding singing instructions, because it would exceed the scope of the present research.

With regard to the main version of the melody (as opposed to the ending-version), seven transcriptions (exx. 1, 3, 5, 6, 10, 12, and 13)[41] designate that phrases A and C are to be sung by the cantor, while phrases B and D are to be sung by the congregation and/or the choir. Exx. 4, 8, and 14 assign phrases A and B to the cantor, and phrases C and D to the congregation and/or choir. Exx. 2 and 7 assign the entire stanza to the cantor.

One final type of instruction concerns the question of whether the piyyutim were ever sung in their entirety in the synagogue. This question touches upon an important matter – the history of Jewish worship – which seems to have changed over time and vary between communities.

We know that medieval Ashkenazi prayer practices were of a strong oral character: the individual worshipper did not read texts but rather recited them by heart or heard them from the precentor (Sheliaḥ ẓibbur). This is especially true with respect to piyyutim, which were originally recited by the precentor alone – as only he had a written version of the long text, while the congregation listened silently or offered short, designated responses (Ta-Shma 2003, 29–33; Goldschmidt 1965b, 9–10). Following the printing revolution, and the subsequent abundance of private prayer books, these prayer practices altered significantly (Steinsaltz 2000, 58).

In the specific context of ‘Akedah piyyutim transcriptions, we assume that in all fourteen examples the first stanza is to be sung. The presence of an ending-version (exx. 4, 8, 13, and 14b, which use the original melody but digress towards the end, and exx. 5 and 7, which provide a completely different ending chant) attests to the singing of the piyyut’s last stanza, at least in some communities. Concerning the remaining stanzas between the first and last, exx. 2, 7, 8, and 14 clearly indicate that all the piyyut’s stanzas were to be sung, yet the other examples offer no information regarding this matter. Also relevant in this respect is Salomon Geiger’s report, specifying that following the first stanza, the congregation continues “until the end” of the piyyut (Geiger 1862, 129), at which point the cantor would sing the last stanza in the melody’s ending-version. This could be interpreted to mean that the congregation would recite the remaining stanzas in a kind of a loud murmur, as is still common in traditional Ashkenazi synagogues (HaCohen 2011, 126–178; Frigyesi 2007).

Meter

Seven of the sources present the melody without fixed meter (exx. 1, 3, 4, 6, 10, 12, and 13);[42] indeed we understand the original melody’s character in this manner. The lack of meter is imperative here because the number of syllables per line varies considerably in piyyutim and other texts sung to the Niggun ‘Akedah. We suggest that originally the poem was chanted in a psalmodic manner, in what could be described as a “double psalmody”. The stanza was divided into two segments of two lines each: each segment had a psalmodic formula containing opening and closing motifs; in between them was a simple recitation tone (tonus currens), which could be repeated as many times as necessary in order to contain a varying number of syllables.

By contrast, the five sources which present the Niggun ‘Akedah with fixed musical meters (exx. 2, 5, 7, 9, and 11) seem to exhibit the influence of nineteenth- and twentieth-century aesthetic conventions. The transcribers’ desire to imbue the ancient Jewish melody with contemporary decorum led them to coerce the original lack of meter into a rhythmic mold. We doubt that these rhythmical transcriptions were performed in reality, even at the time of their transcription (see Adler 1989, xxxvi–xxxvii), because they lack the flexibility necessary for the melody to adapt to different texts.

Idelsohn’s transcription in triple meter (ex. 11), which also includes the contradictory instruction “free time”, seems especially questionable. Nevertheless, Cantor Michel Heymann’s live singing (exx. 14a-b), in which he endeavored to preserve an elastic triple-meter pattern in the melody whenever possible, may echo an old tradition, thus providing some justification for Idelsohn’s transcription.

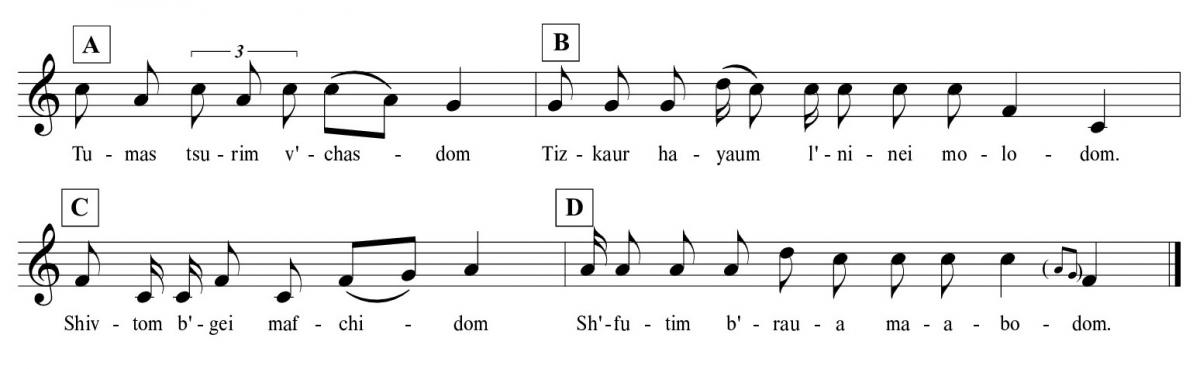

Melodic Structure

Niggun ‘Akedah is a periodic melody constructed of four phrases (marked A, B, C, D in our transcriptions), the first two serving as an antecedent section and the last two as a consequent section. All of our sources agree on the general structure of phrase A. It begins with a recitation pattern alternating between the notes A and C’ and it ends on the notes A–G.[43] They vary, however, with regard to the use of B♭: most of the sources use it either as a passing note between C’ and A, whereas the others do not use it at all. Our sources show great variances for phrase B. While seven sources (exx. 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, and 14) begin on G, ascend to D’, then down to C’, which again serves as a recitation tone, and end on the cadence A–G–F; five sources (exx. 1, 2, 3, 6, 8) begin with the note A, continue with a recitation tone on C’ and end with the half cadence F–C. All the sources agree on phrase C: it begins with recitation tones alternating between F and C and ends with the partial cadence F–G–A (with one exception, ex. 6 by Maier Kohn, where the partial cadence is F–B♭–A). Similarly, the sources concur with regard to phrase D: it begins with a recitation tone A and ends with the final cadence (C’)–A–G–F (again with the exception of no. 6 in which the cadence is the fifth C’–F).[44]

Ex. 4 differs from all the above. It provides a variant beginning for phrase A which is sung from the second stanza onward, beginning by descending from the high F’ to C’ before continuing with the melody. This device was probably intended to enhance the bravura of cantorial singing. Phrase B ends with a half cadence F–D (sic!). Considering that the same ending appears in Levi’s transcription of all the stanzas and since we appreciate his vast knowledge of the cantorial tradition, we must rule out a mere error on his part. Levi does not provide the usual melody for phrase D, only the variant of the last stanza leading into the next prayer; and so it is unclear how the regular melody was supposed to end according to this tradition.

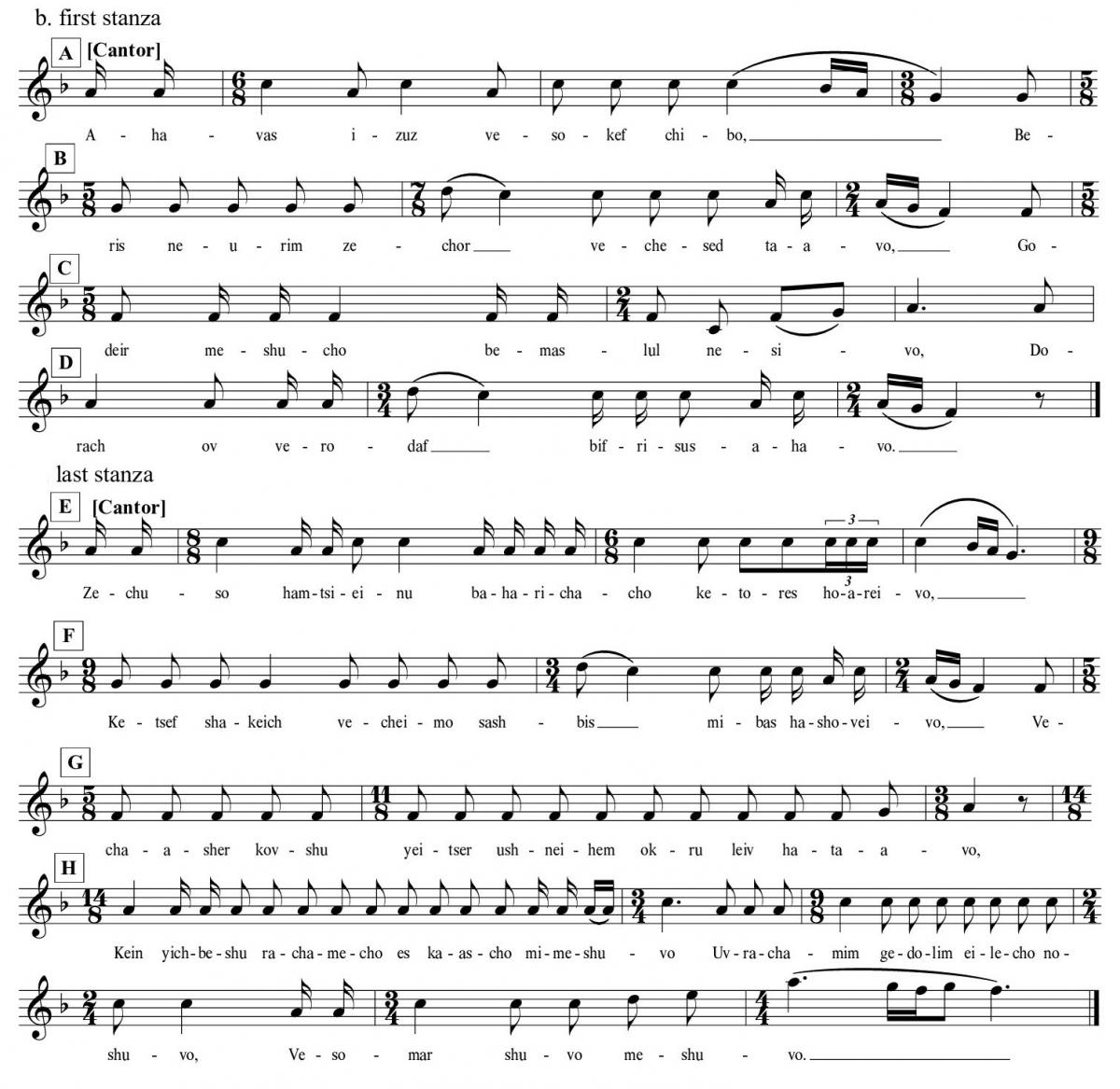

Considering all the above, we suggest a model of the melody as would apply to the ‘Akedah poem Tummat ẓurim. The melody is given here in two versions: one according to the majority of the transcriptions (exx. 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14a and 14b), and another based on fewer transcriptions (exx. 1,2,3,8 [cantor’s part], and 12). We believe that the first version represents a more modern rendition of the melody, dating most likely from the nineteenth-century, whereas the second version appears to be older (see ex. 15)

Example 15. ‘Akedah melody reconstruction (newer version)

The ʽJoyful’ Major and the Pentatonic Scale

When consulting nineteenth century cantorial compendia like Abraham Baer (ex. 7), Katz & Waldbott (ex. 5) and Ogutsch (ex. 9.), the mode of the ‘Akedah melody appears to be in major. Indeed, all present the melody in major keys. How can we reconcile the joyfulness usually associated with the major mode (Heinlein 1928, 101–142) with the sadness of the texts chanted to it? Israel Adler raised this very question as a general issue with respect to the Ashkenazi liturgical chants, in the introduction to his Hebrew Notated Manuscript Sources:

One of the surprising phenomena of Ashkenazi synagogal chant is the cleavage which may sometimes be observed between the grave ethos of the text of the prayers and the joyful ethos of the melody. (Adler 1989, xl)

Adler settles the apparent contradiction by mentioning a Talmudic passage which implies that divine worship must be performed through joyous singing: “[W]hich service [of God] is it that is ʽin joyfulness and with gladness of heart’? – You must say: It is song” (BT Arakhin, 11a). He also mentions that Hasidic thought celebrated the verse from Psalms 100:2, “Serve the Lord with gladness, come before His presence with singing,” quoting a Hasidic story which explains why the liturgical confession of sins should be chanted with an uplifting melody: “A slave who cleans the garbage from the king’s court […] sings niggunim [melodies] of joy since he causes contentment to the king.” (Adler, 1989, xl; Agnon 1987, 32)

Still, we should question the ethos accorded to the major mode and consider that cultural meaning of a musical idiom may change over time; as Idelsohn writes,

[I]t is impossible and futile to pass judgement as to whether these tunes are capable of calling forth in our days the ideas and sentiments they are supposed to express, since so many centuries have passed since the time of their creation. (Idelsohn 1929, 135)

Therefore, it could well be argued that associating the ethos of the major mode with gladness is not necessarily a universal trait, especially in pre-modern times. Indeed, even in classical European music, for example, one of the saddest arias in the opera repertoire was composed in the major mode: the lament Che faro senza Euridice, in which Orfeo mourns the death of his beloved wife, in Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice.[45]

What is more, as was noted above, the pre-modern German song concerning the suffering of Jesus which Idelsohn sought to compare with the “‘Akedah tune” was also sung in the major mode. Furthermore, the Gregorian Tonus Lamentationum to which verses of the biblical Book of Lamentations are sung during the Holy Week is in the medieval “sixth mode”, the early predecessor of the major mode.[46] But above all, as we have seen, even in the early nineteenth-century Salomon Geiger considered the Niggun ‘Akedah to be particularly sad.

Additionally, in all Ashkenazi traditions, the High Holy Days confessional prayer “’Ashamnu, Bagadnu” (referred to in the Hasidic story above), during which Jews beat their chest with each word as an expression of remorse, is chanted in the major mode.[47] Likewise, we have encountered Western Ashkenazi transcriptions of Shelishiyyah piyyutim (another type of piyyut said in Seliḥot services) in the major mode (Idelsohn 1932, 93 [no. 255]). It is thus possible that Ashkenazi Jews associated constellations of the major mode with sadness or contrition, especially when the chants or melodies were sung at a slow tempo.

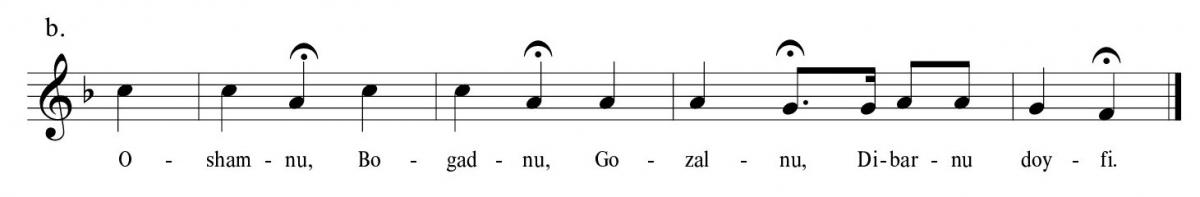

Furthermore, the versions which appear to be in the major mode are constructed on the hexachord F–G–A–B♭–C’–D’ plus a lower sub-tonic note C, a fourth below the tonic. One version (ex. 6) is even limited to the pentachord F to C’, three versions (exx. 5, 7, and 10) use the full hexachord, and two additional sources (exx. 9 and 13) add an occasional high F’ leap to the octave, which creates a yodel-like grace note. It is quite significant that even the transcriptions presenting the melody in a seemingly major mode avoid the leading tone E’. This six-tone scale recalls the medieval hexachordum molle (the soft hexachord). There is even greater resemblance to the old chants: at least six out of our fourteen sources, namely the three earliest (exx. 1–3) and Idelsohn's three examples (exx. 10–12), present the melody in the pentatonic mode of (C), F (tonic)–G–A–C’–D’. Can we therefore assume that what appears now to be a melody in the major mode, is actually a modification of an older pentatonic one?

In this regard the proposition made by Jacques Chailley concerning the evolvement of pentatonic chants into diatonic ones is significant (1966, 84–93). Chailley drew on Constantin Brailoiu’s article “Sur une mélodie russe” (Brailoiu 1953), which explored the universality of the pentatonic scale. Among Brailoiu’s observations he noted the important role of the auxiliary notes, known in Chinese culture as “pien.” These notes fill in the interval of the third which is always presented in the pentatonic scale, thus enriching the pentatonic music in various cultures. Chailley applied Brailoiu’s observations in depicting the evolution of European medieval modality, suggesting that the psalm-tones developed from pre-existing pentatonic chants through the gradual incorporation of auxiliary pien notes. He proposes that in medieval European music, these auxiliary notes became stepping stones to transfer the music from the pentatonic scales into the diatonic ones. Hence behind various psalm tones that may appear diatonic, a former pentatonic version may have existed.

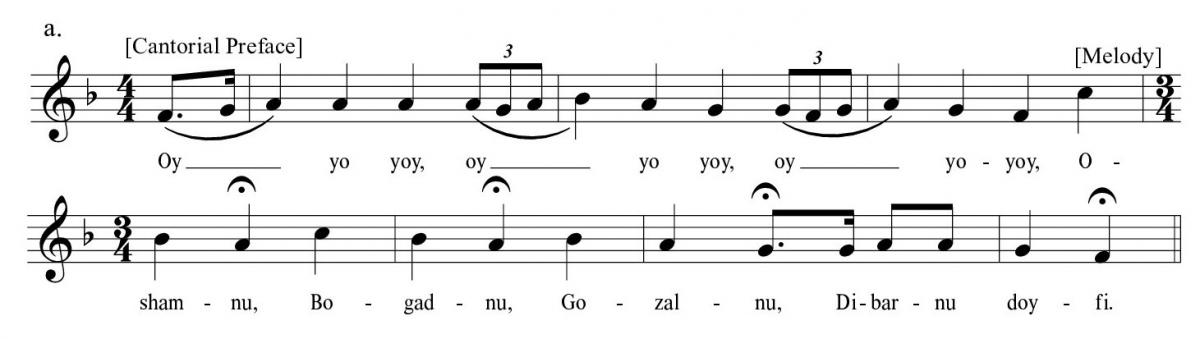

Within the context of the Niggun ‘Akedah, we regard the B♭ passing tone, or upper auxiliary tone, that appears in eight transcriptions (exx. 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, and 14a-b) as a pien tone. It should be noted that Cantor Heymann’s singing (exx. 14a-b) is almost purely pentatonic, except for one B♭ sung as a mere passing tone. Taking our cue from Chailley, we can suggest that the pentatonic transcriptions (exx. 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12) display versions that date back to medieval times (ex. 16)

Example 16. ‘Akedah melody reconstruction (older version)

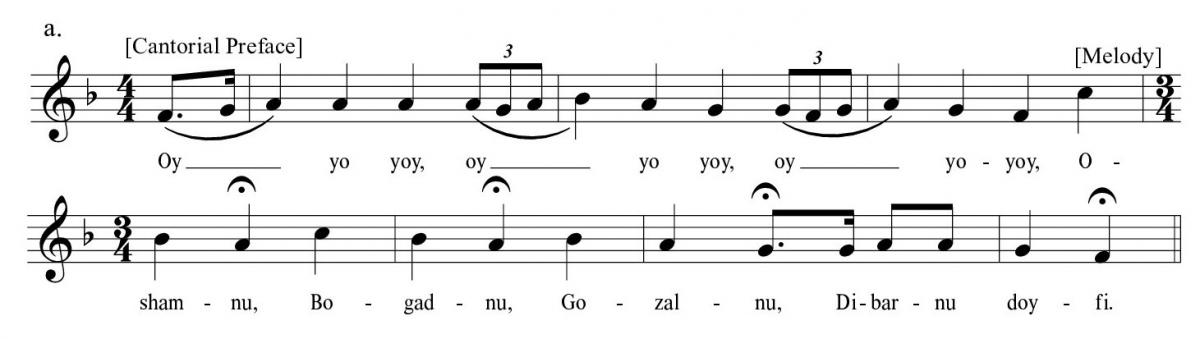

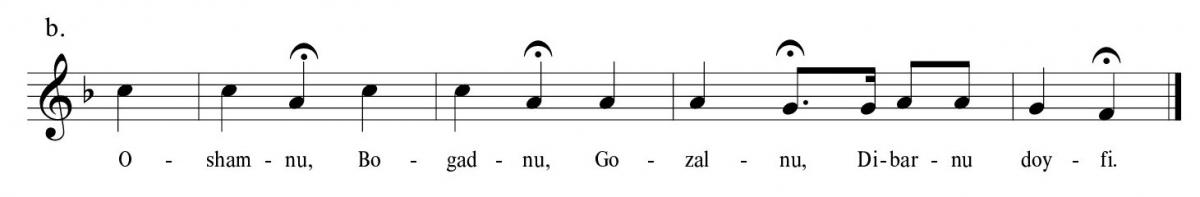

A quaint anecdote in this respect is the observation that one of the oldest versions of the niggun ‘Akedah in our collection, ex. 3, has been transcribed by Gerson Rosenstein, the first Jewish organist of the nineteenth-century German Reform movement, who advanced the new ritual of the Hamburg Temple. His transcription is a purely pentatonic melody with no hints of the major mode as it was understood in the nineteenth century. Within these lines, it is possible that additional chants in the Ashkenazi High Holiday repertoire, which today are considered to be in the major scale, were formerly sung in pentatonic mode.[48] Thus, for instance, if we eliminate the pien tones from the famous Eastern European melody for the minor confessional ’Ashamnu, Bagadnu, which today sounds like a tune in the major mode (ex. 17a), we arrive at a simple proto-pentatonic chant of four notes (ex. 17b), which may have perhaps constituted the original version. It is quite clear that the non-verbal preface to this melody (“oy-oy-oy”) was originally what cantors used to call “shtel” or “shtele,” namely a wordless melodic introduction to a traditional chant (Avenary 1960, 193). Similar “shtelen” were commonly sung before other High Holy-Day prayers such as the ʽAmida or ʽAleinu Leshabeaḥ prayers (Baer 1882, 258 (no. 1165, ʽPolnische Weise’); Neʼeman 1973, 65 [no. 110]). All of them were added to the original chants at a late age. In the case of ’Ashamnu, Bagadnu, however, the shtel merged with the chant and it was sung by the cantor and the congregation whenever the chant was repeated (see ex. 19; Ne’eman 1973, 196 [no. 26])).

Example 17a. “Ashamnu”, Eastern European Melody (transcribed by Schleifer)

Example 17b. “Ashamnu”, Suggested Original Melody

This hypothesis requires further research. However, in the specific case of Niggun ‘Akedah we believe that we have sufficient evidence to conclude that this melody was originally pentatonic. As such, Niggun ‘Akedah belongs to a very early stratum of the Ashkenazi synagogue chants and melodies, dating back to the Middle Ages.[49] Consequently, it is not unfeasible that the medieval and early modern references to Niggun ‘Akedah point to the same melody as that represented in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century transcriptions above, and a variant of which is still sung today in some Jewish communities that follow the Western Ashkenazi rite.

Conclusion

We suggest that the melody recorded in the transcriptions above is indeed the medieval Niggun ‘Akedah. For centuries it was preserved through oral transmission, until it was first written down in the nineteenth century and recorded in the twentieth. The medieval character of the melody complements the texts of the early ‘Akedah piyyutim, which were composed shortly after the First Crusade, in the wake of its agonizing impact.[50] Indeed, we propose that Idelsohn was right in arguing that Maharil sang a variant of the extant melody during the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century. The fact that we have the transcription of such an ancient melody (even if through late and limited transcriptions), enriches our knowledge in the barely documented field of pre-modern Jewish music. On the one hand, our study highlights the impressive capability of oral transmission in preserving a melody over centuries and across a vast geographical area; on the other hand, it reflects the changes that this melody apparently underwent, particularly with the addition of a pien-tone to the pentatonic mode that de facto saw the melody’s “majorization”. Our conclusions also enhance the understanding of other pseudo-major melodies in the High Holiday liturgy, and indeed the musical idiom of this liturgy at large.

The ‘Akedah melody may sound joyful today, but in the past it was perceived as sad and connected with texts expressing the solemnity of the High Holidays, as well as the bitter memory of Jewish martyrdom (Kiddush Hashem). Niggun ‘Akedah was applied in synagogue services to texts designated as ‘Akedah piyyutim, but in fact also signaled to the lay public that such poems were being recited. Thanks to this tune, most worshippers in the synagogue, who were Yiddish-speakers and could not understand the enigmatic Hebrew language of the piyyutim, could recognize when an ‘Akedah piyyut was sung, and perhaps comprehend its cultural and emotional meaning.

We noted above the proximity between some Ashkenazi Kinah piyyutim and Gezera piyyutim, written in quatrains and referring explicitly to the Binding of Isaac, and the genre of ‘Akedah piyyutim. We repeat here our assumption that Kinah piyyutim, too, may have once been sung to Niggun ‘Akedah. We thus discern that Niggun ‘Akedah defines a textual corpus beyond the Seliḥot service, which includes piyyutim that are not Seliḥot, as well as Yudisher shtam and additional songs in Yiddish, all sung to its melody. All the texts in this corpus mention the Binding of Isaac, connecting it with contemporary or past persecutions suffered by Jews in Europe, while proclaiming faith in God and/or accepting persecutions as His will.

The earliest reference to Niggun ‘Akedah dates back to the fourteenth century. The contrafactum references to this melody in Yiddish literature, however, changed, thereby reflecting social dynamics and the popularity of sung texts in Jewish Ashkenazi society over the years—from Niggun ‘Akedah throguh Niggun Yudisher shtam to Niggun prostitser kedoshim and ultimately back to Niggun ‘Akedah. The last contrafactum reference to this melody in Yiddish literature dates from the seventeenth century (probably 1670). If we consider Yudisher shtam (all versions of which lack musical references) to be a contrafactum of the Niggun ‘Akedah as well, this date can be pushed to 1728, its last known edition. In Hebrew liturgy, by contrast, the name Niggun ‘Akedah has been used continuously within the liturgical setting until the present day.

Finally, we see that even the power of religion is limited. The wane and near disappearance of the Niggun ‘Akedah in the twenty-first century is strongly linked to alterations in Jewish worship. Due to historical circumstances and cultural change, and especially because of the Holocaust, many congregations abandoned the chanting of piyyutim in general. Many contemporary Maḥzorim contain no ‘Akedah piyyutim (Tal 1995; Scherman et al. 1996; Langer 1998, 182–85) and few synagogues in the world today recite ‘Akedah piyyutim, let alone according to the melodic heritage of the Western Ashkenazi rite. Under such circumstances, the unique melody of Niggun ‘Akedah is in danger of disappearing altogether from the Ashkenazi synagogue repertoire. Recently there have been attempts to revive the Western Ashkenazi liturgical tradition. Within this movement, the Niggun ‘Akedah may be preserved.

Endnotes

* We would like to extend our thanks to Simon Neuberg and Peter Lenhardt for their learned advice, and to Geoffrey Goldberg for his valuable commentary on Maier Levi’s melody.

[1] The Talmud relates that Satan urged God to test Abraham’s faith with the request that he sacrifice his son (BT Sanhedrin, 89b), while Midrash Tanḥuma (Vayera, 23) describes Sarah’s suffering and sudden death upon learning of her son’s fate. Shalom Spiegel (1967) revealed an ancient version of the story claiming that Isaac was in fact killed by Abraham but was later miraculously revived (Ginzberg 2003, 224–237).

[2] According to some traditions, Sarah conceived Isaac on Rosh Hashanah (BT Rosh Hashanah 11a), Isaac was born on this day (Zohar, Parashat Toledot), and the Binding of Isaac took place on this day too (Pesikta Rabati 40). Similarly, the ram’s horn blown on the High Holidays serves as a reminder of the piety displayed by Abraham and Isaac during the episode of the ‘Akedah (BT Rosh Hashana16b; Zunz 1920, 136–137; Spiegel 1967, 55; Noy 1961).

[3] We have come across some piyyutim of another type which may suit this context, namely Gezera piyyutim concerning the Crusades (Zunz 1920, 139; Fleischer 2007, 470; Weinberger 1998, 5–6, 184–187; Einbinder 2000, 540).

[4] According to Midrash Rabbah 56:3, Isaac asks his father to bind him tightly lest his trembling invalidate the sacrifice.

[5] Seliḥot are recited during the High Holiday season from four to nine days preceding Rosh Hashanah (according to the day of the week upon which Rosh Hashanah occurs) until the end of Yom Kippur, with the exclusion of Rosh Hashanah and Saturdays (Ganzfried, Kiẓur Shulḥan ʽArukh 128:5). However, within these Seliḥot it is customary to say ‘Akedah Piyyutim only on the morning of Rosh Hashanah Eve, and during the days following Rosh Hashanah until the end of Yom Kippur, inclusive.

[6] Many, if not most, ‘Akedah Piyyutim, can be found in Goldschmidt 1965b, 1970, 1993.

[7] Such as Meḥayye piyyutim which are said during the repetition of the second benediction of the ʽAmida prayer (Zunz 1920, 65; Weinberger 1998, 50–51; Spiegel 1967, 29–33). The liturgical rites of other Jewish communities also include piyyutim concerning the Binding of Isaac, for example twelfth century poet Yehuda ben Shmuel Ibn Abbas’ poem ʼEt shaʽarei raẓon lehippateaḥ (when the gates of mercy open), which is sung in oriental Jewish communities during Rosh Hashanah services before the blowing of the shofar at the end of the Morning Service, and in some communities in the Yom Kippur Neʽilah Service.

[8] Even within the same piyyut the lines are not always uniform in length, for example ʼIm ʼafes rovaʽ haken (Goldschmidt 1965, 190).

[9] This stanzaic structure could be viewed as a tercet followed by a refrain, a form known in the study of piyyutim as Muwashshaḥ. However, in the poems we saw, only the last word of the fourth line recurs, forming a so-called Pseudo-muwashshaḥ, Weinberger 1998, 91–94, 165, 327; Goldschmidt 1965b, 101, no. 39 (Mefalleti ʼeli ẓuri); 134, no. 49 (ʼAzay behar mor).

[10] Goldschmidt 1970 ii, 661 (ʼEmuna ʼomen ʽeẓot). Some regard Benjamin b. Zeraḥ’s ʼAhavat ʽezez as a monorhyme (Weinberger 1998, 223).

[11] Entitled ‘Akedah fun Yitskhok (and not, Shira fun Yitskhok, ʽSong of Isaac’; Falk 1938, 248; Weinreich 1928, 133; Dreeßen 1971, 145–148).

[12] Some researchers of Yiddish literature believe that this song was sung in the synagogue (Zinberg 1943 xi, 123; Shmeruk 1978, 119). For a detailed comparison between the Hebrew ‘Akedah Piyyutim and Yudisher shtam see Roman 2016, 175–194.

[13] These contain Minhagim (customs), prayers, prose exempla, Pirkei ʼAvot, songs, etc. (Dreeßen 1971, 10, 13, 19, 25).

[[14] From the beginning of the fifteenth century Jews migrated from German territories to northern Italy, continuing to speak Yiddish there and writing and printing Yiddish books until the beginning of the seventeenth century (Turniansky, Timm, and Rosenzweig 2003).

[15] Idelsohn 1932, xxxii; Adler 1989, xli; Seroussi et al. 2001. Some transcriptions of Ashkenazi synagogue chants appeared earlier and were notated by non-Jews: among them are Johannes Böschenstein’s and Caspar Amman’s transcriptions of the Torah cantillation motifs at the beginning of the sixteenth century and the Passover Seder melodies which were printed in Johann Stefan Rittangel’s Liber rituum paschalium of 1644 (Adler 1989, 556-557, 878).

[16] Such contrafactum singing instructions may be found in many Ashkenazi sources (Zunz 1920, 116; Idelsohn 1929, 381-382).

[17] Only in one case did we find an instruction to sing an ‘Akedah piyyut to a tune other than Niggun ‘Akedah (ʼAta huʼ ha’elohim, in: Goldschmit 1993, 104 [no. 5]).

[18] On the connection between the theme of circumcision and the Binding of Isaac, see Sabar 2009, 9–27; Goldin 2002, 175–176. We thank Chana Shacham-Rosby for drawing our attention to the latter source.

[19] Eleazar Hakalir’s Kinah piyyut for the Ninth of Av: איך תנחמוני הבל (How can you console me with vain words?; Feuer 1996, 286-291. This Kinah piyyut is written in monorhymed quatrains with an additional refrain. Its stanzas can therefore be sung to the Niggun ‘Akedah, but the refrain would necessarily include an additional musical motif, perhaps one that is sung by the entire congregation. We could not trace Western Ashkenazi musical transcriptions for this, but Eliyahu Schleifer is aware of an Eastern Ashkenazi melody. The tune he knows is completely different to Niggun ‘Akedah, and is comprised of four musical phrases and a refrain.

[20] The editions are very similar. Indeed, the main difference lies in the musical instruction: while one edition includes the contrafactum reference Be-niggun ʽAkedah, the other states that it should be sung Be-niggun ’Addir ’ayom venora’, a three-lined stanzas song usually sung on Saturday nights (Baer 1936, 316; Scherman 1979, 270-272). Perhaps the third line was sung twice in order to apply this melody to a four-lined stanza, or perhaps this reference was simply a mistake.

[21] Unfortunately, we have been unable to find any information on this melody, though its name suggests that it may have been a German song, perhaps about the city of Braunschweig.

[22] The first edition (Prague, ca. 1713) survived in a lithographic copy which is found in the University Library Johann Christian Senckenberg, University of Frankfurt am Main (online access PURL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:2-2225); the second edition was printed in Amsterdam, apparently in 1714 (Steinschneider, 1852–1860, no. 3685; Steinschneider 1905 i: 138, no. 129).

[23] One, a moralizing song, is found in the Bodleian Library in Oxford (Steinschneider 1852–1860, no. 3639); the other, an obscene parody, is in the so-called Wallich Manuscript (Rosenberg 1888, 258; Butzer, Hüttenmeister, and Treue 2005, 1-29; Matut 2011 i: 140-151, ii: 199-214).

[24] A detailed comparison of Yudisher shtam and the ‘Akedah piyyutim is in Roman 2016, 175-194.

[25] Idelsohn (1929, 380–381) mentions Niggun Yudisher shtam yet barely comments on it, only mentioning that it was once a popular melody to which other songs were set. He insinuates that it is in fact identical with Niggun ‘Akedah, but contradicts himself a few pages later (383), distinguishing both names as two separate melodies.

[26] Written by Salomon Geiger (1792–1878) and first printed in Frankfurt, 1862, this book sought to preserve the old Minhag Frankfurt through detailed instructions for the synagogue rites pertaining to every day of the year. The Hebrew title of this work is: ספר דברי קהלת: המודיע מנהגי תפלות ק'ק פראנקפורט על המאין [...].

[27] Namely ’Elohim ʼal domi ledami, ʼEt hakol, kol Yaʽakov nohem and ʼEmunim benei maʼaminim. This liturgy reflects the view that in the Ashkenazi liturgical calendar, the morning of Rosh Hashanah Eve is regarded as the culmination of the preliminary penitentiary days, leading up to the New Year. Therefore, its Seliḥot service is the longest one of the entire year. Additionally, since Rosh Hashanah is associated with the Binding of Isaac, the intricate Seliḥot service which begins on the Eve of Rosh Hashanah at dawn includes a number of ‘Akedah piyyutim.

[28] They are written in monorhymed quatrains, allude to the ‘Akedah story, and mention the word ‘Akedah. See for example the Kinah piyyutim in Haberman 1971, 61, 64, 69, 84, 107, 111, 137, 159, 172, 186, 203, 209, 213.