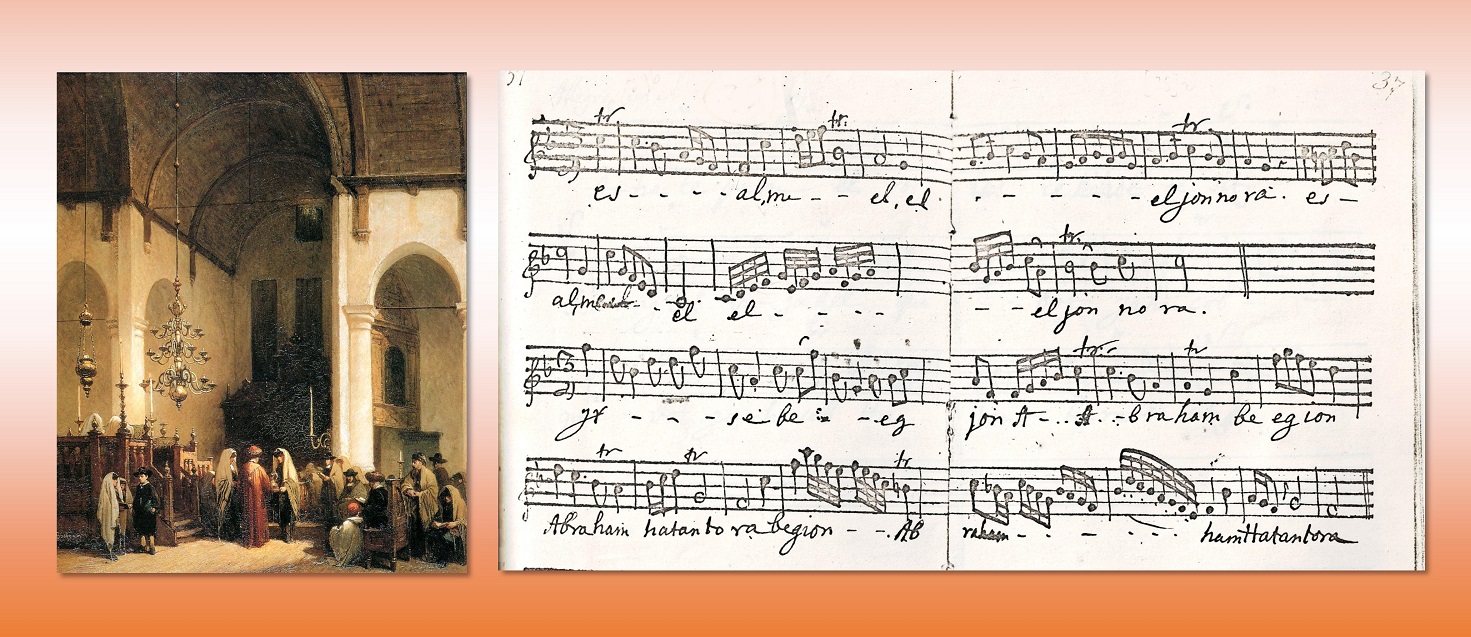

On March 15, 1899, the distinguished scholar, cantor, composer and avid manuscript collector Eduard Birnbaum of Königsberg published a short article modestly titled “Unsere erste Musikbeilage” (“Our first musical supplement”) in Israelitischer Lehrer und Kantor, an insert of the Berlin-based periodical Die jüdische Presse. Birnbaum introduces in it the score of Kol haneshamah, a Hebrew piece by composer Cristiano Giuseppe Lidarti (1730-after 1794). Arguing against writers who maintained that the music of Jewish communities can be reduced to a common source, Birnbaum proposed that musical diversity is the natural state of Jewish culture. Lidarti’s setting was a case exemplifying this hypothesis. The score, based on an 18th century manuscript that Birnbaum had copied during his 1887 sojourn to the Ets Haim library at the magnificent Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, is one of several works by Jewish and few non-Jewish composers (such as Lidarti) composed on behalf of the Portuguese community in the late Baroque style. It attests to the delicate and rather unique (from the Jewish perspective of the period) Western musical taste of the small but affluent Sephardic community of the Netherlands in the 18th century.

Intended for performance on special occasions such as Simhat Torah and Shabbat Nahamu (when the anniversary of the foundation of the Portuguese synagogue in 1675 in celebrated), these artistic pieces for solo or choir with instrumental accompaniment where hardly known to the public when Birnbaum published Lidarti’s Kol haneshamah in 1899. However, they were destined to remain in relative obscurity because only an antiquarian such as Birnbaum would find them worthy of historical interest. Even the “father” of Jewish music research, Abraham Z. Idelsohn, did not dedicate more than a footnote to these Jewish Portuguese scores from Amsterdam, which he knew via the copies in Birnbaum’s collection at the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati.

Fast forward to the 1950s. A young Israeli scholar studying in Paris, Israel Adler (1925-2009), ignited a renewed interest in written music sources of historical European Jewish communities. Driven by a nationalist-oriented agenda to constitute a history of Jewish music in Europe which would resonate with mainstream Western music history, Adler toured post-war Europe in a comprehensive search for manuscripts from decimated Jewish communities. Also trained as a librarian and paleographer, he uncovered unique music materials in Holland, Italy, France, Great Britain and Germany, not only in libraries and secured archives but also in the attics of small, mostly inactive synagogues. Some of these materials miraculously survived the Holocaust. Adler eventually dedicated his dissertation to the “Art musical practice of some Jewish communities in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries,” which he finished upon his return to Israel in the early 1960s. This thesis was submitted to the Sorbonne and was eventually published (Israel Adler, La pratique musicale savante dans quelques communautés juives en Europe aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. 2 vols. Études Juives 8. Paris: Mouton, 1966.)

After establishing the Jewish Music Research Centre (JMRC) at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1964, Adler developed a research infrastructure which allowed him to process, transcribe, edit and publish the music of the Jewish manuscripts he located in Europe. Some of these pieces, edited by Adler and published by the Israel Music Institute, were performed at the ceremony marking the foundation of the JMRC and the Department of Musicology at the Hebrew University, in the presence of Maestro Arthur Rubinstein, who established the first chair in Musicology. In 1978, the Boston Camerata conducted by Joel Cohen recorded a selection of Adler’s editions and issued them in the long-play record titled Jewish Baroque Music.

However, it was a festive concert held at the Hebrew University, on the occasion of the World Congress of Jewish Music on August 3, 1978, which would launch the very modern phenomenon subsequently labeled the “Jewish Baroque.” This impressive concert was conducted by Maestro Avner Itai with the participation of a distinguished gallery of performing artists in cooperation with the Israel Festival and the Israel Broadcasting Authority. The program included Lidarti’s Kol haneshamah, the very same piece that Birnbaum published in 1899, as well as other works by the 17th century composer Salamone Rossi of Mantua, and from the Comtat Venaissin (today Provence, France), the Italian communities of Casale Monferrato and Sienna, and the Portuguese community in Amsterdam. The recording appeared in the long-play Synagogal Music in the Baroque, the first audio recording issued by the JMRC (1978), which still circulates today as a collectors’ item, more than four decades after its release. These recordings were later reissued in cassettes, CDs and eventually as files in digital platforms online, showing that the public fascination with the “Jewish Baroque” phenomenon never decreased.

Since 1978, the repertoire of the “Jewish Baroque,” as edited and published by Adler, spread to the four corners of the world. Moreover, the discovery (also by Adler) of the Hebrew oratorio “Esther” score at the University of Cambridge library in England in the late 1990s added the largest known work of Jewish Baroque music to the repertoire. As with previous works produced by Adler, “Esther” was published by the Israel Music Institute, recorded commercially and performed, premiering on May 30th, 2000 at a celebration marking the 75th anniversary of the Hebrew University's founding.

The “Jewish Baroque” musical repertoire is performed assiduously at festivals and academic conferences. The appeal of these works to producers and audiences is easy to understand. Listening to high art music with Hebrew sacred texts “elevates” Jewish musical culture, and introduced the Jews to the mainstream European art music narrative even before the Emancipation. It needs to be stressed however that the phenomenon of Western art music in European Jewish communities during the Baroque was extremely limited, centered on very specific events such as a circumcision ceremony of a well-to-do family, the inauguration of a new synagogue, or the devotion of mystical Jewish confraternities such as “Shomrim laboqer” in Italy. Only in the Portuguese Jewish community of Amsterdam do we find a steady application of Baroque music aesthetics to the core liturgy, particularly throughout the eighteenth century, mostly set to the text of the qaddish, the qedushah and few piyyutim. One has therefore to confine the “Jewish Baroque” to its historical proportions and contextualize it as a phenomenon of Jewish modernity’s drive to create a “normative” historical Jewish music narrative.

The very limited repertoire of the Jewish Baroque made public through performances and publications has concealed the existence of many manuscripts from the Portuguese community of Amsterdam, uncovered and described in detail by Adler in his massive Hebrew Notated Manuscript Sources up to circa 1840: A Descriptive and Thematic Catalogue with a Checklist of Printed Sources (2 vols. International Inventory of Musical Sources B: IX.1. Munich: Henle, 1989). Adler did not publish this material in its entirety for a simple reason: all the music in them is for one voice only. These sources are the manuals of the Amsterdam cantors, containing the pieces that they composed for liturgical services which, following Jewish practice, were devoid of instrumental accompaniment or polyphonic arrangement. Yet, the harmonic background of these solo pieces is easy to figure out due to the formulaic musical language of the period. Thus the addition of instrumental accompaniment within the stylistic parameters of late Baroque and Galant style could be relatively easily accomplished.

Almost twenty years ago, Maestro David Shemer, founder and artistic director of the Jerusalem Baroque Orchestra, arranged at my request several of these additional Portuguese liturgical compositions, drawn from one of the richest manuscript sources, one compiled by the 18th-century cantor Joseph ben Isaac Sarfaty of Amsterdam, now housed at the National Library of Israel (Ms. 8o Mus. 2). On July 21, 2002, these arrangements were performed in the opening concert of the conference of the European Association of Jewish Studies, held at the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, the very same sanctuary in which this music was first performed without the instrumental accompaniment. These “new” pieces of the “Jewish Baroque” were performed for a second time at the National Library of Israel, in Jerusalem on December 15, 2010, in a concert titled Kol haneshamah, duly dedicated to the memory of Prof. Adler, who passed away in 2009.

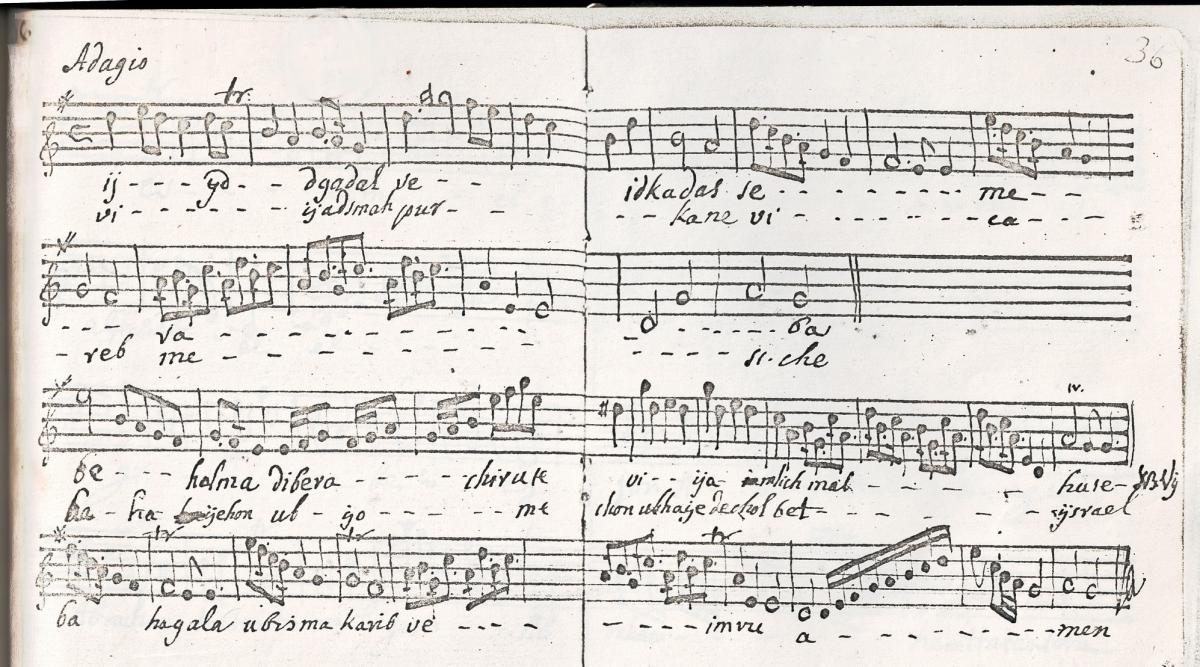

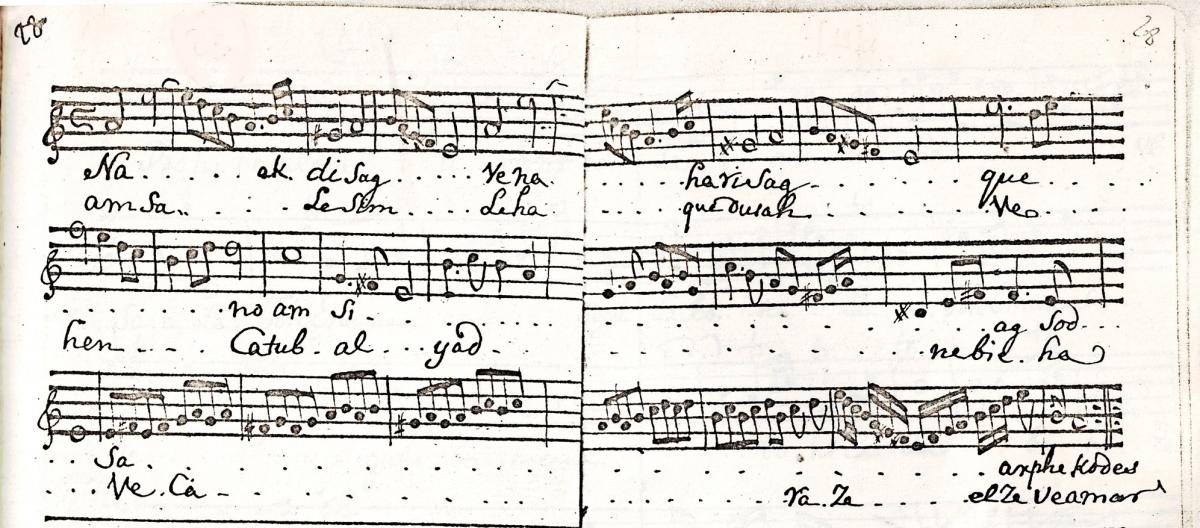

The Jerusalem Baroque Orchestra (JBO) returned to the “Jewish Baroque” with additional innovations, in the concert held on January 13, 2019 in the historic concert hall of the YMCA in Jerusalem. The program included the world premiere of unheard pieces from cantor Sarfaty’s manuscript, arranged this time by Dr. Alon Schab, senior faculty member of the University of Haifa. They included items 20 (Odu la’el qir’u bishmo), 32 (Yitgadal veyitqadash) and 3 (Yehe sheme rabba) respectively in the aforementioned manuscript arranged as a mini-cantata. We titled this cantata “Song for the Inauguration of the Portuguese Synagogue” because the text of the first piece, Odu la’el qir’u bishmo, penned by Rabbi Isaac Aboab da Fonseca (1605-1693), was written for that grand event which took place on Shabbat Nahamu, August 2, 1675 (10 Av 5435). Although the original music for the inauguration of the magnificent Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam did not survive, there is a remote possibility that cantor Sarfaty preserved in his compendium traces of this old piece. Rabbi da Fonseca’s poem ends with a transition to the Qaddish, evidence that his poem was originally conceived as a liturgical reshut, an introductory piyyut that Sephardic cantors used to insert at the opening of the public prayer.

These compositions in their new arrangements expand the horizons of the by-now ubiquitous “Jewish Baroque,” that “invention” of modernity that does not cease to attract audiences to concert halls to this day. We are glad to include here the score of Dr. Schab’s setting of the “Song for the Inauguration of the Synagogue” as well as the recording by the Jerusalem Baroque Orchestra conducted by David Shemer. Also included is the poem Esh’al me-El tzur and the correspondent Qaddish set to the same melody arranged by David Shemer. Names and bios of the performers appear in the attached program of the JBO concert of January 13, 2019.

- Edwin Seroussi

Materials:

Qaddish whose melody is incorporated into the Cantata for the Inauguration of the Amsterdam Synagogue. Source: National Library of Israel, 8o Mus. 2.

Odu L'Adonay, Cantata for the Inauguration of the Portuguese Synagogue of Amsterdam, arranged by Alon Shab, Jerusalem Baroque Orchestra, January 13, 2019.

Score for Shir Hanukkat Beit Hakneset arranged by Alon Shab, version for bass

Score for Shir Hanukkat Beit Hakneset arranged by Alon Shab, version for tenor

Esh'al me-et tzur, original manuscript from National Library of Israel, 8o Mus 2.

Esh'al me'el tzur and Qaddish, arranged by David Shemer, Jerusalem Baroque Orchestra, January 13, 2019.

Qeddushah, original manuscript from National Library of Israel, 8o Mus. 2.

Naqdishakh, sung by Claire Meghnani, Jerusalem Baroque Orchestra, January 13, 2019:

Concert Program from January, 2019, Jerusalem Baroque Orchestra