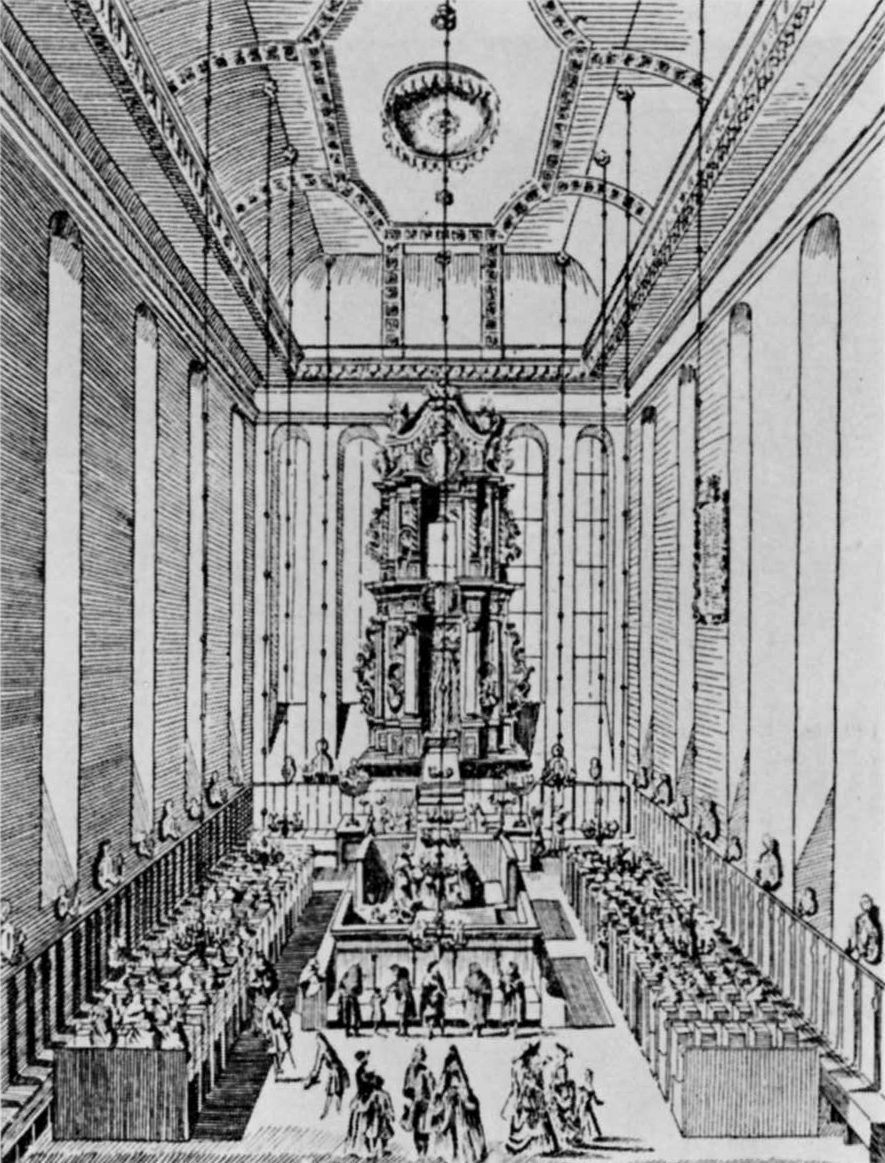

This project aims to map, analyze and make German Jewish liturgical music (minhag Ashkenaz) accessible to the scholarly community and to the public at large. The historical period under investigation dates from the early 19th century up to World War II, investigating these practices within a broad European cultural context. The synagogue is conceived not only as a ritual space but also as a location for the symbolic public display, through the language of music, of new evolving aesthetic ideals, of Jewish public emotions, of cross-cultural intersections between Jews with the surrounding Christian society, and of marking of communal and regional distinctions. The focus is on large synagogues established in major urban centers as a by product of Jewish urbanization and the rapid emergence of a Jewish bourgeoisie and on the effects of these urban models on synagogues of smaller towns.

German Jewish Sacred Musical Intersections

The basic theoretical underpinning of this project is that a new paradigm of Jewish liturgical music developed in German-speaking communities parallel to the gradual rise of German music as a “universal” language against which other musical nationalisms in Europe defined themselves. Similarly, local synagogue repertoires from London through Trieste to Odessa evolved in conversation with or resisting the German-Jewish paradigm as it crystalized since the second quarter of the 19th century mainly in Vienna, Berlin and Paris.

The paradigm consists of several elements. First, a modern conceptualization of an endangered “heritage” of solo cantorial music (at times framed within a Jewish national discourse) in need of documentation, preservation and dissemination. These processes demanded the “cleansing” of this heritage from foreign accretions that have obscured its pristine primordial forms. Second, the enrichment of this “pure” cantorial heritage with new choral music, usually for four voices a capella (substituting older improvised Ashkenazi forms of choral accompaniment), partially based on traditional tunes or consisting of originally composed pieces by Jewish and non-Jewish composers. Debates about the inclusion or exclusion of female voices in synagogue choirs are an important aspect of this musical innovation. Third, the use of instrumental music, most particularly the organ was a subject that resulted in extensive discussions. Finally, these three components entailed the professionalization of cantors, choristers, choirmasters and instrumentalists and the disciplining of an orally transmitted traditional music lore through a theoretical discourse. Eventually, these two last social processes blurred the distinction between the religious and non-religious spheres of Jewish music-making since late 19th-century Europe. This last issue is a crucial theoretical postulate of this project.

Such developments were made socially feasible through the development of networks of individual musicians whose authority was acquired through their vocal and compositional skills, proficiency in the repertoire and access to prestigious pulpits. These musicians and their networks engaged in diverse types of relations (such as teacher-disciple, soloist-chorister, guilds’ membership, mutual compliments, etc.). They promoted new aesthetic ideals of ritual through the publication and distribution of liturgical music, the establishment of cantorial schools and associations, as well as the specialized and general Jewish press. In this last respect, we emphasize printing technology as well as reception and criticism as integral components in the consolidation of the narratives that maintained and stimulated musical changes in German synagogues during the period.

In present times, similar networks of cantors, music collectors, and other lay leaders in Jewish communities have been established. Such networks are focused on and dedicated to the investigation, collection, preservation and transmission of religious values, customs and folklore of German Jewry as they existed prior to the Holocaust. As such, material available in state libraries as well as in private collections of these globally acting networks (such as the above mentioned network Machon Moreshes Ashkenaz) is of high importance.

We propose to depart from the limited number of musicians that have been addressed in the literature on German synagogue music, particularly the “triumvirate” of Salomon Sulzer (Vienna), Louis Lewandowsky (Berlin) and Samuel Naumbourg (from Munich but active in Paris). The “German model” found diverse forms of expression that reflect local aesthetic sensibilities, stylistic preferences, individual initiatives, communal memory as well as financial and performance capabilities. All these vectors are decisive in determining the musical products, practices and reception characteristics of each location and even of each synagogue. For example, the German model developed in the Munich synagogue parallel to Sulzer’s in Vienna and the Munich tradition remained independent throughout the 19th century. Even the model of Breslau developed by Moritz Deutsch, a disciple of Sulzer, was different from that of his mentor. In Königsberg, the model was idiosyncratically developed by Hirsh Weintraub, an Eastern European cantor, and continued by Eduard Birnbaum in a Sulzerian style. Moreover, the German model was not only found in synagogues in large cities but also in smaller ones, such as Braunschweig, where the scale of the model was much more modest than in Vienna or Berlin. Finally, the 20th century witnessed even more variegated stylistic developments of the model, such as in the work by Samuel Lampel in Leipzig.

Central to this project is also the attempt to review not only networks of musicians, musical traditions, repertories, genres, and styles that were prevalent in the regions explored, but to reassess Jewish liturgical services as a Gesamtkunstwerk, i.e. as they were performed and experienced in themselves and in relation to other occasions in the Jewish calendar. Concepts such as “mood”, “participation”, “sense of community”, “temporal flow” and of course, sonic space, would guide this reassessment, allowing for new insights into Jewish life in Central Europe in the last centuries, as they have transpired and transformed. This analysis will be carried against the general background of European art music, especially during the crucial, transformative 19th century, with attention to concepts such as the “religion of art music” and the growing roles of Jews as composers, performers, and audiences in the wider European sonic sphere.

Among other well-entrenched concepts in studies of Ashkenazi liturgical music, this study will also challenge the binary construct of Western and Eastern Ashkenaz that has been criticized in other fields of Jewish studies. The German model spread well beyond Western Europe, becoming the inspiration for the music of many “Germanized” synagogues eastwards, from the Baltic to the Black Seas via Congress Poland, Galicia and Hungary and westwards, to the Americas. Conversely, many “Germanized” cantors and composers were “Ost-Juden” who incorporated elements of their autochthonous repertoires and performance practices into the German model. Moreover, there is also a North-South European axis to be explored, as Protestant versus Catholic environments informed Ashkenazi synagogue musical practices.

The innovative potential of this project is thus patent. We propose to avoid studying Jewish liturgical music from a discrete perspective, as a self-contained unit sometimes exposed to “external influences.” Our approach attempts to release the music created by Jews and Jewish communities from a provincial status and to integrate them within the narratives of European music history. Such a comprehensive approach does not underestimate the uniqueness of the synagogue soundscape and its variegated layers of musical memory. On the contrary, it enables scholars to examine more carefully individual and collective choices as they were pending in the ongoing attempts of negotiating subjectivities, especially in periods of rapid social and technological transformation. By perceiving the consolidation of these unique repertoires within a wide European context we hope to liberate Ashkenazi liturgical music from its status as a curiosity of European music. Also studying this musical culture against the backdrop of more general tendencies in Jewish social and cultural history promises to bring fresh insights into long-debated issues, such as Jewish acculturation, community building and belonging, Ost-West relations, proto-Zionist, Zionist and anti-Zionist affiliations.

In spite of its predominant focus on the past, the results of this project are pertinent to the present and future of Ashkenazi liturgical music in Europe and elsewhere. Contrasting processes are taking place within this musical practice as the result of modernity and globalization. A lachrymose attitude to the “vanishing” of “traditional” Ashkenazi liturgical music is pervasive among some scholars and practitioners. Indeed, traditions and memories were lost forever during the Nazi era and the Shoah. As a research strategy, however, this “decline” is often conceived as entailing the erosion of a unique identity and the proposal of urgent actions to re-instate its past glory. Other forces contend that only a thorough innovation of repertoires and performance practices, a process that can answer to the aesthetical sensibilities of the contemporary generation, will secure its future. Our approach attempts to merge these opposing perspectives, believing that the revival of the Ashkenazi synagogue and the increasing interest on this musical repertoire can benefit from the results of such an integrative project both in practical and theoretical terms.

To attain our goals we will capitalize on the wealth of unknown or under-researched musical sources found in libraries and archives, notably printed and manuscript scores, archival recordings, private estates of composers, cantors and choirmasters as well as cantors’ journals and ethnography with the goal of tracing the historical unfolding of new aesthetic ideals and systems of social representation in Ashkenazi synagogue music. The project consists of six stages, each deploying its own methodology:

- Establishing an infrastructure for the documentation and research of Ashkenazi liturgical music in Hannover and Jerusalem. Taking advantage of existing resources at the Europäisches Zentrum für Jüdische Musik (EZJM) at the Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien in Hannover and the Jewish Music Research Centre, we propose to locate, catalogue and make accessible online historical resources and new ethnographical materials found in German institutions, as well as in Israel and the USA. In so doing, the database “Soundscape Synagogue” (www.nachhaltigkeit-ezjm.de) that is currently set up at the EZJM can function as an additional medium to research and represent relevant resources.

- A critical and contextual examination of these repertoires in terms of the constitution of an awareness of “tradition/s” and the dialogue of these “tradition/s” with the surrounding non-Jewish European soundscapes. We shall emphasize critical time nodes such as the encounter of Jews with modernity in the late 18th century, the internal negotiations of Jewish identities and subjectivities deriving from the East/West conundrum in the course of the 19th century, and processes of secularization of liturgical music in the early 20th century.

- A mapping of the institutionalization of Ashkenazi liturgical music such as anthologizing efforts and other modes of encoding and standardization will also be an object of critical inquiry. These practices will be investigated in relation to their dialectical relations with changing performance practices and creativity.

- In light of the above dialectics, an in-depth analysis of these repertoires in musical- performative terms, attempting to establish their particular intersections between events, genres, modes, traditional vs. “progressive” musical styles, liturgical vs. paraliturgical elements etc.

- Following recent scholarly attention to German Jewry in Germany after World War II (Brenner 1997; Geller 2005; Kauders 2007) the project will extend to ethnographies of present-day liturgical practices and their diverse dialogues with the past as well as the restructuring of these practices through the establishment of schools of cantors, ordination of clergy, and choral performances.

- Editions of selected scores, digitization of unavailable rare sources, performances of unknown works, recordings and design of educational programs and materials. Capitalizing on developments in digital humanities, we anticipate that an additional contribution of this project will consist of a digital map displaying intersections of time and place in Ashkenazi liturgical music within the application Jewish Music Mapped of Da’at Hamakom (https://music.jewish-cultures-mapped.org) developed under the direction of PI Seroussi.