לך אלי תשוקתי נוסח יהודי בבל החזן ר' משה חבושה

Lekha Eli Teshuqati: Experiencing total self-surrender to God in song

Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra’s (1089–1167) piyyut Lekha Eli Teshuqati, a pillar of the Sephardic High Holiday’s liturgy, has recently become a staple of the trend of performing religious Hebrew poetry as Israeli popular music. This piyyut is among Ibn Ezra’s most outstanding lyrical creations, marked by a distinct classical poetic structure and profound spiritual content. The poem is a striking testimony to the way this poet, halakhist and biblical commentator of medieval Spain, combined his rational wisdom with his burning religious emotions and ability. In this unique devotional poem, he leads the worshiper into an experience of complete surrender and total devotion in which body and soul, matter and spirit, are united in an act of absolute dedication to God. Its emotional power, coupled with the simplicity of its accessible language and elegant poetic structure, continues to inspire contemporary audiences.

Translation of the first four lines:

To You, my God, is my craving; in You are my desire and my love.

To You belong my heart and my innermost being; to You my spirit and my soul.

To You my hands, to You my feet, and from You is my very nature.

To You my bones, to You my blood, and my skin together with my body.

Unlike the vast majority of liturgical poetry created by Hebrew poets in medieval Al-Andalus, Lekha Eli Teshuqati achieved remarkably wide circulation due to its inclusion the Sephardic liturgical canon. Once it entered prayer compilations, it was copied in many manuscripts, eventually reaching the printing press as soon as Jewish liturgical orders started to be printed in the early-sixteenth century. Today, the piyyut appears in Sephardic mahzorim at the opening of the Yom Kippur evening service (right before Kol Nidrei). This placement is probably due to the fact that, in addition to inspiring the human soul to yearn for God in its opening section, it contains in its second section a personal paraphrase of the viduy—a confession of sins in alphabetical order, recited by worshippers in all the Day of Atonement services. While the liturgical viduy appears in the plural (e.g., Ashamnu), in the poem it is expressed in the singular (ve-ashamti). This aligns with the poem’s overall first-person perspective, which is consistently singular and centers on personal confession, dedication, and the pursuit of individual salvation.

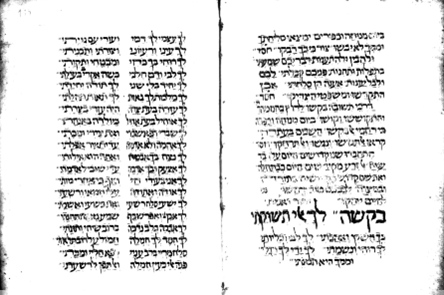

However, is spite of the noticeable textual connection to the themes of the High Holydays, Lekha Eli Teshuqati was not originally intended for Yom Kippur. It appears in early sources as a baqqashah, an exercise in private devotion to be recited by the worshipper at the dawn, before the daily morning prayers. The special status of this piyyut as a baqqashah is reflected in it position at the very beginning of the daily prayer order. See, for example, its appearance in a late medieval Sephardic prayerbook (Figure 1):

Figure 1: Lekha Eli Teshuqati as a baqqashah in Sephardic Siddur, 14th-15th century, The Russian State Library, Moscow, Ms. Guenzburg 1230, fol 113

It continued to appear as a baqqashah at the opening of one of the earliest printed Sephardic prayerbooks (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Seder Tefillot (Venice 1546), detail of fol. 14.

Lekha Eli Teshuqati has a simple poetic structure, modeled on the classical Arabic qasida, that induces an ecstatic sensation in performers and listeners. It consists of ninety lines, each containing two hemistiches, scanned in the Arabic hazaj meter (‿---‿---/‿---‿---, called marnin in Hebrew), with all lines rhyming on “ti.” In the opening twenty-one lines, the poet addresses God directly with the same word, “Lekha” (“To You”) followed by a cumulative list underscoring the totality of the human being—spirit, emotions, body, and blood—all offered to the Divine Presence. This poetic devise creates a litany-like rhythm that conveys a sense of absolute devotion. Most of the lines in the second section of the poem (including the vidduy in lines 37-45) open with the conjunctive syllable “ve” (“and”), further extending the elated atmosphere created in the first section. The poem closes with lines expressing the poet’s hope for expected mercy, forgiveness and salvation from God in retribution for his atonement of sins.

Lekha Eli Teshuqati: The Sephardic Musical Tradition

In most Sephardic communities, Lekha Eli Teshuqati is sung to a simple melody that is consistent throughout all corners of the Iberian Jewish diaspora. Such consistency indicates that this melodic pattern was fixed to this text and likely belongs to the earliest strata of this liturgical repertoire. The manner of performance varies from community to community: it can be sung by the congregation, by various soloists, or in alternation between soloists and congregation.

The melody consists of four short motives, each covering a hemistich and ending on a clear cadence on pitches 5, 3, -2 and 1 respectively of the natural minor scale. Therefore, the melody repeats with each two lines. Although it has a fixed beat and a rhythmic pattern recurring across the four motives (short, long, long, longest), reflecting the poetic meter, when performed by soloists, the melody is rendered with a more fluid rhythm.

In versions sung by cantors from Turkey, the melodic progression of this melody recalls the seyir (path) of makam Hüseyni. Indeed, Turkish cantors employ microtonal inflections of pitches 6 and 2 that recall the tuning of this mode. You can listen here to a performance of Lekha Eli Teshuqati by the renowned singer Haim Effendi.

However, intonations of this melody can vary across communities, producing different “maqamic” perceptions, as Idelsohn had already noted when comparing Sephardic versions from Jerusalem, Salonika and Aleppo (Idelsohn 1923: 48, nos. 258, 261, 264 and 282). The following version from Baghdad exemplifies a different intonation to the same pattern in an Arab-speaking Middle Eastern community.

The following table (Seroussi 1988: 274), comparing five Sephardic Ottoman versions of this melody—some notated more than a century ago— demonstrates its consistency along time and place: (1) Vienna, ca. 1880; (2) Izmir, sung by Moshe Vital, NLI Sound Archive, 1963; (3) Bucharest, 1910; (4) Sarajevo, c. 1950; (5) Jerusalem, c. 1910.

This melody became one of the musical “themes” of the High Holyday liturgy and is used to sing other texts, such as the qaddish. Moreover, it is applied to other texts, most notably the havdalah song Noche de Alhad (incipit: Al Dio alto con su gracia), a Judeo-Spanish paraphrase of the piyyut Be-moza'ei yom menuhah, attributed to R. Abraham Toledo (fl. late seventeenth century) which remained very popular throughout the Ottoman Empire (see notes to the recording of Lekha Eli Teshuqati by Haim Effendi).

Considering the simplicity and functionality of the Lekha Eli Teshuqati tune, it is not surprising to find similar melodies in the Judeo-Spanish and Spanish musical realm set to poems of similar structure. Melodies consisting of four motives with the cadential pattern 5, 3, -2, 1 abound, for example, in the Spanish and Judeo-Spanish romancero, as shown by Etzion and Weich-Shahak (1988, 1993). Romances share with Lekha Eli Teshuqati the poetic structure of many lines of two hemistiches with the same meter and rhyme adapted to a melody of four motives with cadences on 5, 3, -2, and 1, that repeats with each two times. One can observe this musical pattern in a late fifteenth-century polyphonic arrangement of the romance “Tiempo es, ell escudero,” included in the Cancionero de Palacio (Barbieri 1890: 503, no. 333).

Lekha Eli Teshuqati: An Unexpected Performance

On September 20, 1988, renowned JMRC ethnomusicologist Yaacov Mazor recorded a performance of Lekha Eli Teshuqati during a tish (an assembly of Hasidim around their Rebbe) on the Eve of Yom Kippur at the Yeshivah Beit Abraham in Jerusalem. How did such a quintessential Sephardic piyyut reached a Hasidic community?

The Slonim Hasidim, a dynasty originating in Belarus, have a peculiar chapter in their history in comparison to other Hassidic dynasties. Its founder, Rabbi Avraham Weinberg, sent in 1873 some of his followers, including his grandchildren, to Ottoman Palestine. They settled in Tiberias, where they interacted with the ancient local Sephardic community, adopting some of its practices. Most members of the Slonim dynasty perished in the Holocaust, but the community was able to reconstitute itself based on its presence in the Land of Israel.

Slonim’s Lekha Eli Teshuqati is a niggun dvekut, an introspective, meditative even hypnotic song, in very slow tempo. The intonation of the niggun is extremely unstable, moving at times in microtonal shifts while the tessitura raises throughout the song in small increments, a staple of the very peculiar Slonim singing style. In spite of its notable difference from the Sephardic traditional tune, this niggun has an uncanny resemblance to it. Above all, the whole extensive text is performed with the “same” repeating melody, a very uncharacteristic trait of Hasidic niggunim. Also, the short-long-long-longer rhythmic pattern of the Sephardic melody can be perceived in spite of the slow flowing rhythm. The only Hasidic “moment” in this piece resides in the addition of a wordless refrain (la-la-la) that divides this long poem into sections of four lines each.

Lekha Eli Teshuqati: The Contemporary Israeli Revival

A meaningful song that expresses the individual’s humble standing before his Creator in such a powerful way—and in clear-cut Hebrew—, Lekha Eli Teshuqati made natural inroads into the contemporary wave of piyyut revival within Israel’s popular music scene. These renditions in popular music greatly contributed to spreading Lekha Eli Teshuqati among non-Sephardic audiences unfamiliar with the poem.

Yemenite singer Yair Gadasi composed a melody for Lekha Eli Teshuqati, which was popularized in 1995 by fellow Yemenite singer Zion Golan, and later, in 2004, by Yoav Yitzchak and Haim Yisrael in Hebrew with a Yemenite accent—so much so that it came to be mistakenly regarded as a traditional Yemenite melody. Over the years, Gadasi’s melody has received numerous cover versions by Mediterranean-pop singers and has become a staple of performances during the High Holiday season.

In 2007, Meir Banai released his album Shema Koli, in which he set traditional Jewish texts and piyyutim either to his own new music or to traditional melodies arranged in new ways. Among the piyyutim featured were Shalom Leven Dodi and El Nora Alila, but the most popular was the new melody he composed for Lekha Eli Teshuqati.[1]

However, the public presence of Lekha Eli Teshuqati in Israeli public life beyond the liturgy did not begin with its revival as a popular song. It had long been sung at the funerals of prominent Sephardic rabbis and is one of the very few piyyutim known to have been used in such a context. Cantor Ezra Barnea recalled in his memoirs that in 1955 his father returned deeply moved from the funeral of Rabbi Shabtai Hizkiyah, the Chief Sephardi Rabbi of Jerusalem, where apparently Lekha Eli was sung, and subsequently requested that it also be sung at his own funeral.

The singing of Lekha Eli Teshuqati at funerals has recently taken another tragic turn. In late August 2024, Ori Danino and five other hostages, who had been kidnapped ten months earlier on October 7, 2023, were murdered in Gaza. Their bodies were recovered and brought back to Israel for burial. Ori Danino, a soldier from an ultra-Orthodox Sephardic family who lived a less observant life, was kidnapped while on leave, attempting to save others during the massacre at the Nova music festival.

At Ori Danino’s funeral, his father, Rabbi Elchanan Danino, recounted how, whenever Ori was unable to attend Yom Kippur services, he asked his father for a recording of their community’s cantor, Yosef Elhadad, that included Lekha Eli. Rabbi Danino then sang the traditional Sephardic-Jerusalem melody of the piyyut, discussed above at length.

As noted, the poem expresses the soul’s yearning for closeness to God, emphasizing the total dedication of body and spirit to the divine. Since it incorporates quotations from the viduy (confessional prayer) which is traditionally recited on one’s deathbed, Lekha Eli Teshuqati is particularly resonant in the context of a funeral. Moreover, since Ori’s funeral took place just before the beginning of Elul, the month of spiritual preparation leading to the High Holidays in which this piyyut also plays a central role, it was especially fitting to sing it at that time of year.

By singing Lekha Eli Teshuqati at the funeral, Rabbi Danino framed his son’s death in captivity as that of a martyr, connecting him to the legacy of revered Sephardic leaders. On the first anniversary of Ori’s death, Rabbi Danino was invited to national television to commemorate the day by singing the piyyut again, this time accompanied by Firqat al-Nur, the Israeli Arab music orchestra. He also recorded a version of the piyyut in memory of his son. In this way, the public performances of Lekha Eli Teshuqati came to signify both the fragility of the individual’s life and the community’s steadfast faith in the Almighty within the complex reality that contemporary Israeli society faces.

__________________

[1] It has over fifteen million views on YouTube and has been streamed more than five million times on Spotify.

References quoted

Barbieri, Francesco (ed.), Cancionero Musical de Palacio. Madrid: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, 1890.

Etzion, Judith, and Susana Weich-Shahak. “The Spanish and the Sephardic Romances: Musical Links." Ethnomusicology 32, no. 2 (1988): 1-37.

Etzion, Judith, and Susana Weich-Shahak. “‘Family Resemblances’ and Variability in the Sephardic Romancero: A Methodological Approach to Variantal Comparison.” Journal of Music Theory 37, no. 2 (1993): 267-309.

Idelsohn, Abraham Zvi. Gesänge der orientalischen Sefardim. Jerusalem- Berlin-Wien, 1923. (HOM IV)

Seroussi, Edwin. Schir Hakawod and the Liturgical Music Reforms in the Sephardi Community in Vienna, ca. 1881-1925: A Study of Change in Religious Music.” Ph.D. diss. University of California, Los Angeles, 1988.