Moshe Cordova

Composer, singer, ‘ud and piano player Moshe Cordova (b. Edirne, Ottoman Empire, 1881 – d. Tel Aviv, Israel, 22.12.1965) was a master of the Turkish makam. Cordova was born in Edirne, an important Ottoman Jewish musical hub since the late 17th century. Our knowledge about Cordova’s early years there is meager. A turning point in his life was the move to Istanbul, together with many of the Edirne Jewish community, following the devastation of this city during the Balkan Wars and World War I. In the capital city, Cordova pursued his career as a synagogue singer and composer. Parallel to his musical career he developed a business in the field of textiles and tailoring. Upon his settlement in Istanbul, Cordova became one of the leaders of the Mafṭirim Choir, a renowned synagogue choir from Edirne that continued its activities in Istanbul.

The Mafṭirim performed Hebrew poetry set to Turkish classical music on the Sabbaths at the Italian Synagogue in Galata. This synagogue was also known as Kal de los Francos (Synagogue of the Europeans) since at least the late 1910s. It was founded by Jews of Italian origin who had broken away from the main body of the Sephardi community, placing themselves under the protection of the Italian monarchy. They named their congregation Comunità Israelitico-Straniera di Rito Spagnuolo-Portoghese di Constantinopoli (Community of Foreign Jews of the Spanish-Portuguese Rite of Istanbul). Their impressive synagogue on Kuledibi Şair Ziya Paşa Street was dedicated in 1886. During its heyday in the early twentieth century, Jewish singers from various quarters of Istanbul, as well as from various cities of the Ottoman Empire, gravitated to the Mafṭirim in order to perform, listen and learn.

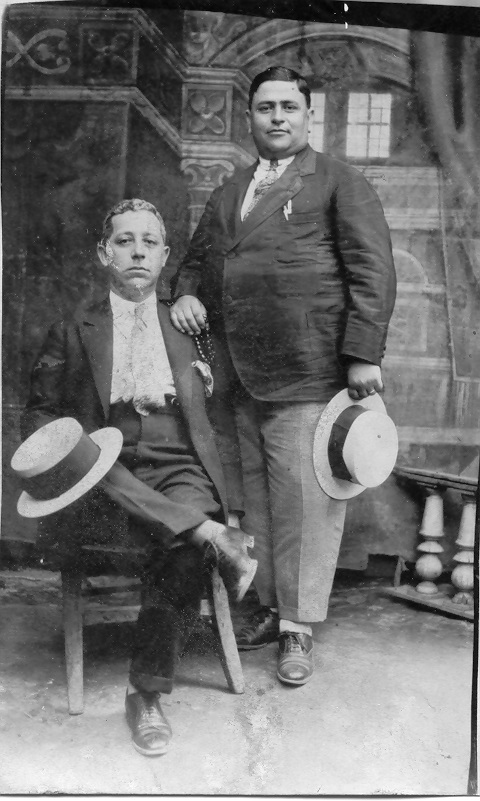

In 1923, with the encouragement of the acting chief rabbi of Istanbul, Haim Bejerano (also a poet and composer), Itzak Algazi, the composer/singer of classical Turkish music from Izmir, moved to Istanbul to become the ḥazzan (cantor) of the Italian synagogue, a position he held until his 1933 emigration from Turkey to France, and later South America. Cordova and Algazi became partners during these years, and recorded Ottoman Hebrew music commercially, some of which is presented in this article.

In 1923, with the encouragement of the acting chief rabbi of Istanbul, Haim Bejerano (also a poet and composer), Itzak Algazi, the composer/singer of classical Turkish music from Izmir, moved to Istanbul to become the ḥazzan (cantor) of the Italian synagogue, a position he held until his 1933 emigration from Turkey to France, and later South America. Cordova and Algazi became partners during these years, and recorded Ottoman Hebrew music commercially, some of which is presented in this article.

Cordova, like Algazi and most of the leading figures in the circle of Ottoman Hebrew Music during early Republican Istanbul, ultimately choose to emigrate. He moved in 1934 to British Mandate Palestine, settling in the fast-growing Jewish city of Tel Aviv, joining a movement of other Ottoman Jews from Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria. For Cordova, immigration to Palestine may have been a necessary step considering the socio-political and economic realities of the new Turkish Republic. However, from the musical point of view, leaving Turkey represented a rupture from the musical milieu in which he grew up and had became a renowned figure among Muslims and Jews. His textile business, not music, became his means of sustenance. His impact as a musician in Israel was peripheral, as interest in Ottoman classical music at the time was confined to a small group of connoisseurs from Istanbul and Saloniki, whose main context of performance was the synagogue.

Southern Tel Aviv and its environs became therefore an alternative, even if diminished, center for Sephardic synagogues whose liturgy was based on the Turkish makam. Cordova rarely performed in Israel in public, but taught Turkish makam to a handful of cantors and appeared in selected radio broadcasts.

Most notable among his disciples was the Jerusalem-born cantor Refael Yair Elnadav (1921-2012). Elnadav, half Yemenite and half Sephardic, became the caretaker of Cordova’s lore. He recorded Cordova with a recording machine that he purchased for this purpose and transcribed some of his pieces in Western musical notation. Elnadav carried Cordova’s legacy with him in his journeys to Cuba and eventually to Brooklyn, New York. In America, Elnadav taught selections from Cordova’s repertoire to a handful of followers.

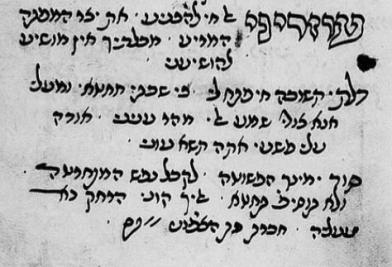

Additional information about Cordova appears in the still unpublished writings by another of his close collaborators, cantor Shim’on Uzziel from Salonika, who had served in Istanbul and then settled in Tel Aviv in 1933, a year before Cordova. Uzziel refers in his writings with admiraton to the cantors and composers from Edirne who resettled in Istanbul. According to Uzziel, Cordova attended prestigious Muslim music schools in Turkey, Dar al-han and Dar al-taalim. Furthermore, Uzziel maintains that Cordova was the musical editor of the important collection of Ottoman piyyutim (religious poems), Shirei Israel be-Eretz Haqedem “Songs of Israel in the East,” together with Binyamin Bekhar Yossef (z”l) and Bekhor Abraham.

Uzziel and Cordova maintained a long-standing collaboration in liturgical music matters. An announcement in the newspaper Heruth on September 16, 1951 advertised a live broadcast of the Selihot service by the “best cantors from the Balkan countries directed by Moshe Cordova and Shim’on Uzziel.” This event was transmitted live by the Israeli Radio from the Ohel Moed synagogue, the central and modern Sephardic sanctuary in south Tel Aviv.

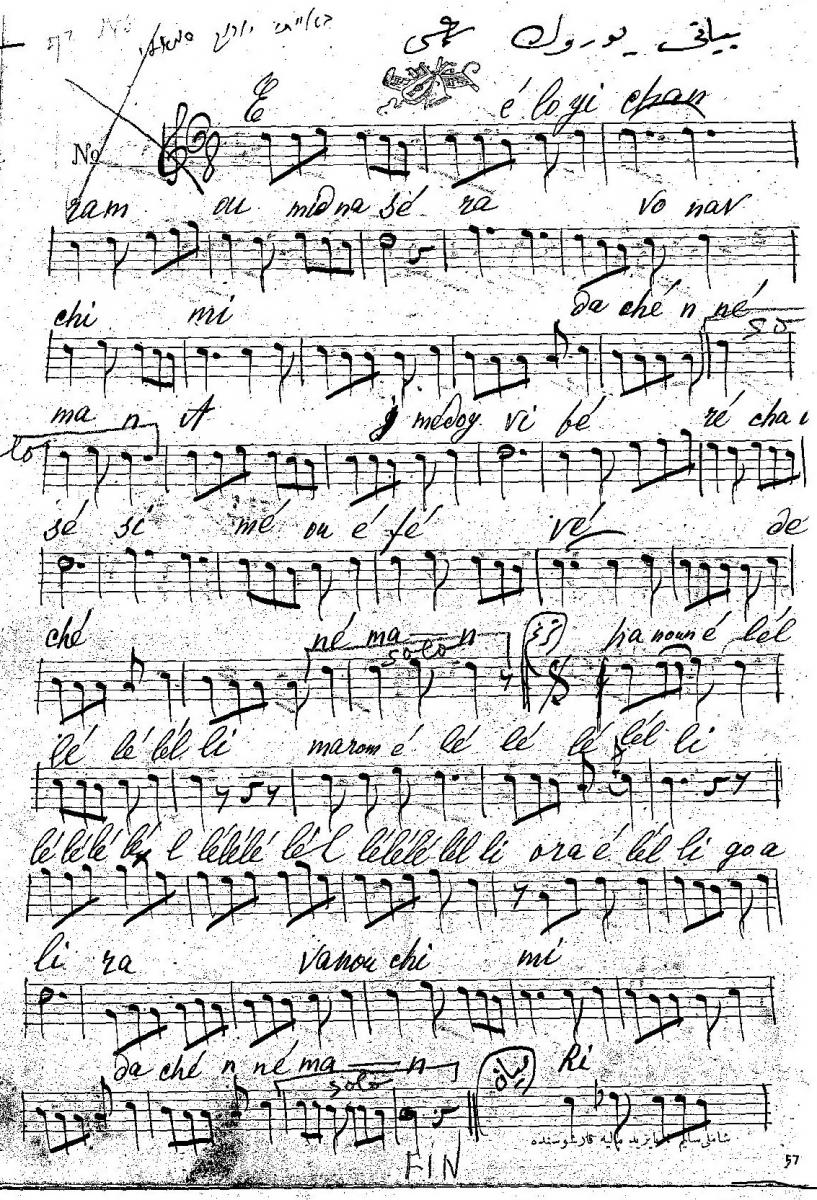

Two substantial collections of scores of more than one hundred compositions by Cordova and other Ottoman Muslim and Jewish composers was kindly shared with me by Cordova’s only close relative in Israel, his nephew Nissan Galili. The second one is the aforementioned collection of cantor Refael Elnadav in Brooklyn.

Few precious recordings of Cordova’s voice have survived. At least two pieces sung by him appear in the old 78rpm discography, both with

him appear in the old 78rpm discography, both with his partner in Istanbul, the aforementioned Isaac Algazi. Both are in the yürük semai genre in makam Beyati. A copy of the recording of the second piece, El lo yishan, by a poet named Aharon, perhaps the late 17th century Aharon Hamon (Yahudi Harun in Turkish) from Istanbul, is available in the Sound Archives of the National Library of Israel. The transcription of this piece in the Cordova collection shows the faithful correlation between the score and the recording.

In the early 1960s the Italian ethnomusicologist Leo Levi interviewed Cordova in Tel Aviv. Three songs are included in Levi’s precious recording. One of them is Odekha el yotzri, a kâr in makam Hicaz. Odekha is a poem by the great late 16th century poet/musician Rabbi Israel Najara from Damascus, the first Jewish master to employ Ottoman makamlar as an organizing principle. The author of the musical setting remains unknown.

Moshe Cordova’s trajectory is one of many stories of late Ottoman Jewish musicians who found themselves in voluntary exile. The number of expatriate experts in Ottoman Hebrew music far exceeded the number of those who chose to remain in the Turkish Republic and maintain the tradition in situ, within a venerable Jewish community. In the early 20th century, inside and outside of Turkey, the practice of Ottoman Hebrew music declined for diverse reasons. The general drop in religious observance and synagogue attendance among Turkish Jews certainly counts as a major factor. However, one cannot discard changing aesthetic considerations. In the case of the Turkish Jews in Israel, the predominance of Arabic music styles (Middle Eastern or Maghrebi ones) in Sephardic synagogues certainly eclipsed the Ottoman Turkish tradition. The Turkish makam became a minority practice among Sephardic Jews in Israel, kept alive only in a handful of synagogues in cities around Tel Aviv, such as Bat Yam and Yahud.

Through the agency of scholarship and a growing interest on the part of Israeli singers of Hebrew religious poetry, Ottoman Hebrew music has resurfaced on stage in the twenty-first century, performed by a young generation of Israeli-born musicians. The 2004 return of the late Refael Elnadav, a caretaker of the Ottoman Hebrew tradition in his own exile in Brooklyn, to coach young Israeli musicians brought the music of Moshe Cordova back to public awareness.

Below is the recording of one of Cordova’s most celebrated compositions, Uri ‘ori, a beste in makam Beyati set to a text by Rabbi Bekhor ben Shlomo Papo, as performed in the 2004 concert dedicated to Cordova and coached by Elnadav. The program notes of this concert are attached below.

Note: this biography is based on Edwin Seroussi’s lecture titled “Moshe Cordova: Turkish Jewish Composer in Exile” read at the 34th ICTM World Conference held in Astana, Kazakhstan on July 17, 2015.