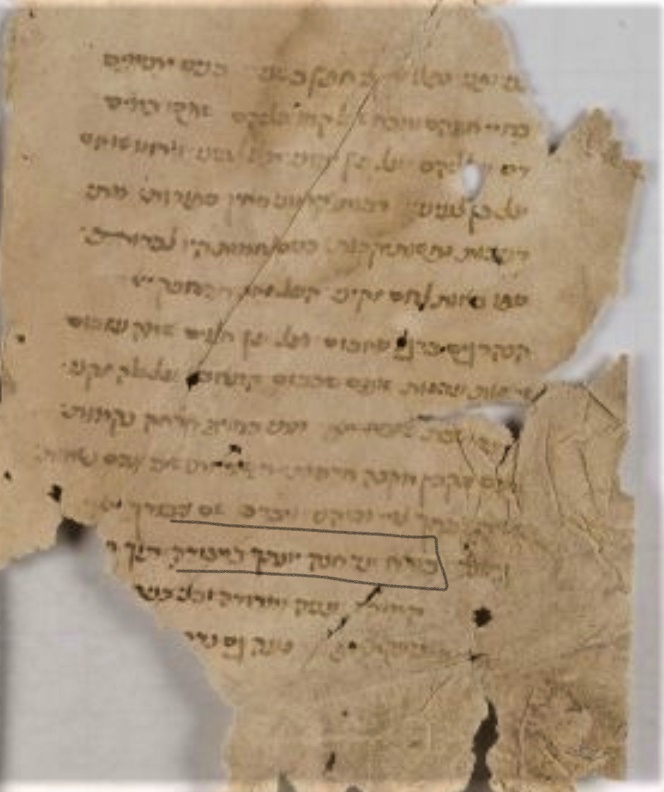

“Bore ‘ad ana” (“Creator until when?”) is one of the most ubiquitous qinot (dirges) in the order of prayers for the Ninth of Av among the Sephardic and Oriental Jewish communities. The identity of the author is unknown, except his name, Binyamin (Benjamin), which is embedded in an acrostic. Consequently, the time and place of authorship are also unknown, although it is most probably a late medieval poem. A loose leaf in the Cairo Genizah contains our poem (highlighted) attesting to its pedigree:

Figure 1. 'Bore 'ad ana,' Cairo Genizah, (JTS, Ms. ENA 3294.4; image courtesy of the Friedberg Genizah Project).

In addition, Joseph Yahalom found 'Bore 'as ana' in a manuscript of qinot from Spain dated in 1481 ('Poetry as an expression of spiritual reality in the late Sephardic piyyut,' [In Hebrew], Exile and diaspora: studies in the history of the Jewish people presented to Professor Haim Beinart on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, ed. Aharon Mirski, Jerusalem: Magnes, 1988, pp. 337-348).

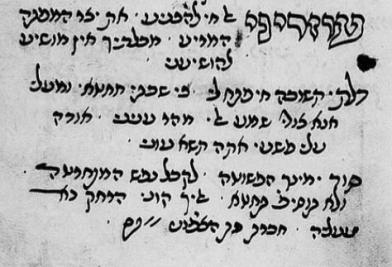

Figure 2. 'Bore 'ad ana,' Thesaurus of Medieval Hebrew Poetry, Israel Davidson

As shown above in the list of printed sources by Israel Davidson’s Thesaurus of Medieval Hebrew Poetry, “Bore ‘ad ana” was mostly known in the Sephardic communities of Italy (Venice, Modena, Livorno) since the early seventeenth century, and not always in relation to the Ninth of Av, but also to other penitential liturgies, such as selihot.

I have studied in great detail the musical setting of this poem in Sephardic communities, emphasizing Spanish-Portuguese and North African versions in the article entitled “Songs of Grief and Hope: Ancient Western-Sephardic Melodies of Qinot for the Ninth of Av.” There it was shown that in spite of notable differences between varations in use among various communities, there seems to be an underlying musical structure tying together all the documented versions of the melody.

“Bore ‘ad ana” is also included in the order of qinot of some Sephardic communities in the Middle East, such as Turkey, Syria and Jerusalem, as shown by various recordings at the Sound Archives of the National Library of Israel as well as in the website pizmonim (where I found the Syrian version). A unique recording of this qinah included in the Sound Archives is the subject of this Song of the Month. Performed by Mr. Nehemiah Hocha, it poses interesting questions regarding oral transmission, the open boundaries of repertoire and the consequences of migrations and other social dislocations on Jewish liturgical traditions. Before addressing the questions raised by the performance by Mr. Hocha, here are some remarks about this notable cantor.

Nehemiah Hocha, cantor and scholar, was born in Zakho, in the Kurdish region of Iraq in 1927 and died in Jerusalem on February 26, 2008. Although he lost his eyesight at the age of four due to poor health care, he revealed himself as a prodigy at the Talmud Torah (elementary Hebrew school), becoming well versed in the Bible, the Talmud, Halacha and Zohar. At the same time, he acquired general education in a state school. From 1947 to 1950, as a young man, he was an underground Hebrew teacher. In 1950, he studied at the renowned Midrash Beth Zilkha in Baghdad prior to his immigration to Israel in 1951. While in Baghdad, he studied violin at the Alliance School, turning music into a profession, as did many other blind Jewish students in Baghdad.

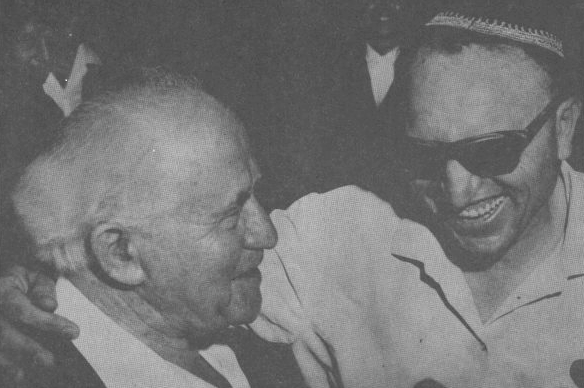

In Israel, Nehemiah raised an entire generation of students in Jerusalem. His prodigious mastering of the Biblical text led him to secure second place in the 1962 International Hebrew Bible contest and in 1964, Hocha went on to win the Israeli Hebrew Bible contest (see above his picture with David Ben Gurion taken on that occasion; source, Hithadshut: Journal of the Kurdish Community in Israel 2 [1975]). He became well versed in the diverse liturgical traditions of Jerusalem, especially the maqam-oriented school of the Ades Synagogue of the Aleppan Jews. For many years, Nehemiah was cantor and preacher at the Zekhut Avot Synagogue in Jerusalem. He sang in a variety of languages and styles, sacred and secular in Neo-Aramaic (the vernacular language of the Kurdish Jews), Kurmanji, Hebrew and Arabic. He was a sought-after musician, faithfully representing the Kurdish tradition in a variety of events, on radio programs and among academic circles. His pleasant voice and extraordinary memory turned him into a major exponent of the Iraqi Kurdish Jewish musical traditions in Israel.

Professor Edith Gerson Kiwi, whose life and work are the subject of a major research project of the JMRC, met Nehemiah Hocha in Jerusalem and interviewed him for many hours between the years 1966 and 1972, covering a wide range of subjects, mostly (but not only) musical. This encounter between the German-born ethnomusicologist and her collaborator, the cantor from Kurdistan, is one of the many meetings of this type characteristic of early Israeli musical ethnography. They rendered precious documents, but were also marred by misunderstandings stemming from the ethnographic clash between different agendas and frames of mind. In this specific case, Gerson Kiwi’s fascination with the Kurdish Jews led her to catalogue each utterance of Hocha as representing the Jewish tradition from Zakho, disregarding the complex biography of the cantor and his musical aspirations.

The recording of “Bore ‘ad ana” by Hocha is one such instance of the aforementioned encounter. Recorded by Gerson-Kiwi on December 5, 1966 (NSA CD 4981), it is part of a one-hour fascinating detailed account by Hocha of all musical practices related to the fast days in the Jewish liturgical calendar, spiced with folk tales related to these events. When the section in the recording dealing with the Ninth of Av starts, Hocha says: “and the cantor starts with the first qinah” and sings “Bore ‘ad ana.”

Recording 1. 'Bore 'ad ana' (NSA CD 4981)

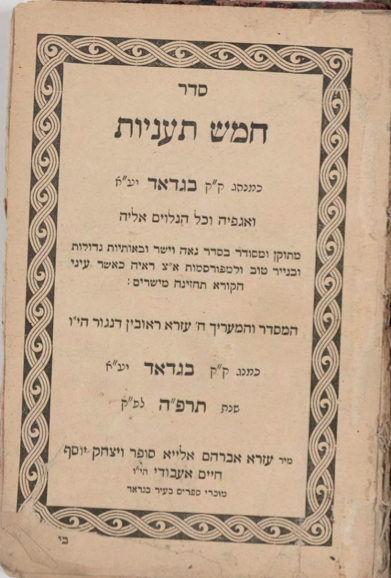

The one and a half minute recording baffled me when I heard it for the first time. To start, the text deviated from the normative version of the poem. But more importantly, I could not find a single recording of “Boreh ‘ad ana” made by a cantor who hailed from east of Aleppo, the great city in Syria. “Bore ‘ad ana” is not included in the order of prayers for the fast day that Hocha himself mentions in the same recording, the “Siddur hamesh te’aniyot.” This prayer book almost surely corresponds to the Seder hamesh te’aniyot ke-minhag q”q Baghdad ve-agapeah (Order of the Five Fasts according to the tradition of Baghdad and its vicinities) that the Ezra Reuben Dangoor press published in 1905/6 and was subsequently reprinted by other publishers (see below the title page of the 1924/5 edition).

Figure 3. Seder hamesh te’aniyot ke-minhag q”q Baghdad ve-agapeah, 1924/5 edition

Before solving the riddle of Hocha's recording, a description of the text is warranted.

Text

“Bore ‘ad ana” centers around the widespread metaphor of the dove symbolizing the nation of Israel. Enemies relentlessly pursue the dove, but it always rises from despair to seek peace and redemption. The poem consists of six stanzas of four lines each: the first three lines consist of eleven phonetic syllables each (5+6), while the fourth consists of five syllables only. The rhyme pattern of the poem is AAAX, BBBX, CCCX, etc, where X is the fixed rhyme of the refrain (“ví”). The three long verses are divided into two hemistiches of five and six syllables respectively, numbered for the sake of easy comparison between the musical renditions, as follows:

| 1a Bore ad anna | 1b yonatekha bimtzudah |

| 2a tokh pah ham-moqesh | 2b aniya u-mruda |

| 3a u-vli vaneya | 3b yoshevet galmudah |

| 4 tzo'eket avi |

Here is the entire text in Hebrew:

בּוֹרֵא עַד אָנָּה יוֹנָתְךָ בִּמְצוּדָה

תּוֹךְ פַּח הַמּוֹקֵשׁ עֲנִיָּה וּמְרוּדָה

וּבְלִי בָנֶיהָ יוֹשֶׁבֶת גַּלְמוּדָה

צוֹעֶקֶת אָבִי

נָעָה גַּם נָדָה מִקִּנָּהּ הַיּוֹנָה

וּלְקֶרַח וְחֹרֶב יוֹם וָלַיְלָה חוֹנָה

הִיא מִתְחַרֶדֶת מֵחֶרֶב הַיּוֹנָה

מִשִּׁנֵּי לָבִיא

יָהּ עֵת עָזַבְתָּ אוֹתָהּ בְיַד טוֹרֵף

אָכַל הַצַּוָּאר וּמָלַק הָעֹרֶף

עָבְרוּ הַשָּׁנִים גַּם קַיִץ גַּם חֹרֶף

אֶשָּׂא עֹל אוֹיְבִי

מִי יִתֵּן אֵלֶיהָ אֵבֶר כַּנְּשָׁרִים

לָעוּף בִּגְבָעוֹת וּלְדַלֵּג בֶּהָרִים

לָבוֹא עִם דּוֹדָהּ אֶל תּוֹךְ הַחֲדָרִים

אָז אֶשְׁכַּח עָצְבִּי

יוֹעֲצִים עָלֶיהָ עֵצוֹת הִיא אֲנוּשָׁה

זָרִים אַכְזָרִים שָׂמוּהָ חֲלוּשָׁה

בְּעֹל כָּבֵד בְּחֶרְפָּה וּבוּשָׁה

גָדוֹל מַכְאוֹבִי

נַחֵם עַל לִבָּהּ אֵל שׁוֹכֵן בִּמְרוֹמִים

דַּבֵּר נֶחָמָה עַל לֵב הָעֲגוּמִים

קַבֵּץ נִדָּחִים פְּזוּרִים בָּעַמִּים

וְגוֹאֵל תָּבִיא

Melodies

A particular characteristic of all the sung versions of this qinah is the repetition of words in specific patterns. Moreover, a refrain is generated between the stanzas corresponding to the second hemistich of the penultimate verse and the last verse of the first stanza: 'yoshevet galmudah, tzo'eket avi.' The pattern of word repetition in the refrain varies in different Sephardic traditions. The common patterns are: 'Avi, avi, avi, yoshevet galmudah, tzo'eket avi, tzo'eket avi' (Bucharest, Larissa, Jerusalem); 'Yoshevet galmudah, tzo'eket avi, avi, avi, tzo'eket avi' (Morrocco); or 'Avi, avi, avi, avi, avi, avi, yoshevet galmudah, tzo'eket avi' (Amsterdam, London). The refrain is pervasive to the point that cantors refer to “Bore ‘ad ana” as “Avi, avi.” The refrain variants are related to the diverse patterns of repetitions of motifs in the melodies of the North African, Spanish-Portuguese and Balkan traditions.

Hocha’s performance, on the other hand, does not have a refrain, but does show repetitions in the following pattern (each line is a musical phrase).

| 1a Bore ad anna | |

| 1a Bore ad anna | 3b yoshevet galmudah |

| 2a Tokh pah ham-moqesh | 2a tokh pah ham-moqesh |

| 2a Tokh pah ham-moqesh | 1b yonatekha bimtzudah |

| 4 Tzo'eket avi |

In short, Hocha has transfigured the text, confusing the order of the verses. The continuation gets even more bizarre for it includes words that do not appear at all in the poem, such as the short verses “harav miqdashi” and “ve-go’el tavi” ending two of the stanzas he sings. Hocha was blind from childhood, so he was singing from memory. However, his musical renditions of other, much longer texts is spotless. Why does he “reinvent” “Bore ‘ad ana”? Or is there an imitation or extension of “Bore ‘ad ana” of which we are not aware?

Recording 2. Abraham Altalef, Izmir

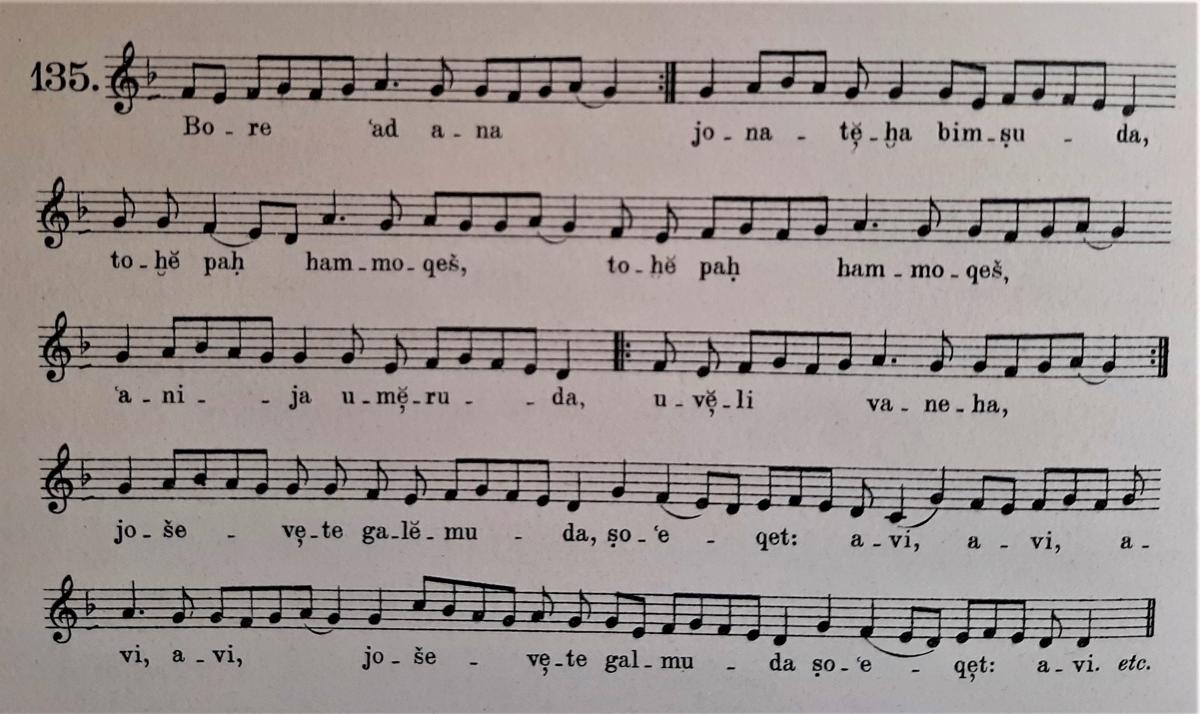

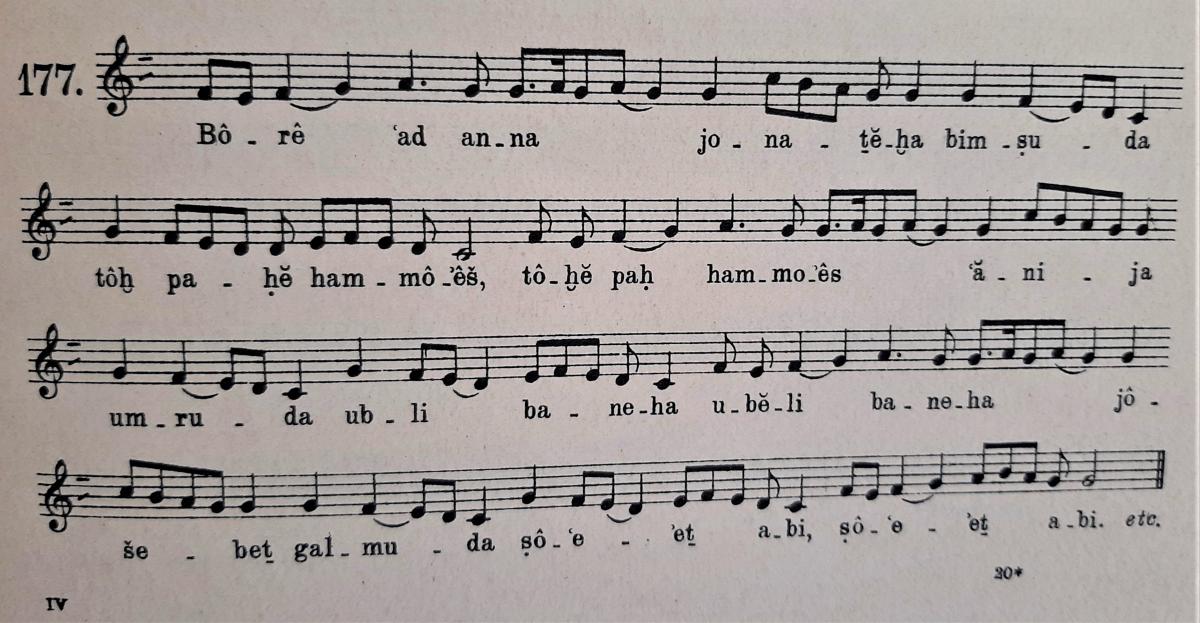

The answer to this query may be found in the old Ottoman space, where the poem was indeed performed with a tune and a pattern of repetitions of the text very similar to Hocha’s rendition. The versions from Salonika and Aleppo recorded by Idelsohn (HOM, vol. 4, no. 135 and 177 respectively) show such repetition of the text as follows: 1a, 1a, 1b, 2a / 2a, 2b, 3a / 3a, 3b 4/ [refrain] 4/3b/4, and so on (Salonika); 1a, 1b, 2a / 2a, 2b, 3a / 3a, 3b, 4 4 (Aleppo, without refrain). Incidentally, “Bore ‘ad ana” does not, unsurprisingly, appear in vol. 2 of HOM that is dedicated to the music of the Babylonian (i.e. Iraqi/Baghdadi) Jews.

Figure 4.'Bore 'ad ana,' Saloniki version, A.Z. Idelsohn

Figure 5. 'Bore 'ad ana,' Aleppo version, A.Z. Idelsohn

While the Salonika version is slightly more akin to the Western Sephardi versions, whose trademark is the refrain “Avi, avi”, the Aleppo version is “circular”, i.e. advancing by repeating the first hemistich of the long verses. The two musical motifs of the tune, one ending on G and one on C, are repeated in the pattern abb1. Hocha’s version is indeed heavily informed by this Aleppo version of “Bore ‘ad ana” (listen to the recording by Victor Antebi and his community, courtesy of www.pizmonim.org) that he most probably learned after settling in Jerusalem in 1951. His close ties to the Ades Synagogue of the Aleppo Jews in the city may account for the adoption that certainly spread to the synagogues of the Kurdish enclaves in the Katamon district of Jerusalem.

Recording 3. Victor Antebi, Aleppo tradition.

Fifteen years later, Cantor Hocha deployed a fragmentary version of “Bore ‘ad ana” by heart (in a faulty, i.e. not deeply rooted memory) to Edith Gerson Kiwi as “Kurdish.” Thus, in this case, the archive memorializes a moment of innovation, the result of recent displacements, liturgical crosspollination and homogenization taking place in Jerusalem in the 1950s, rather than an established tradition.

We are thankful to Mrs. Batya Mazor-Hoffman for her generous sharing of information about Cantor Hocha. She is at the present engaged in a project to preserve the musical heritage of the Kurdish Jews, with emphasis on the recorded lore of Nehemiah Hocha.