Nuestro Señor as sung by Gimol Bentolila, 1981.

Nuestro Señor Eloheinu/Las tablas de la Ley: A Song for Shavuot

Our song of the month concerns a Sephardic song commonly sung on the Passover and Shavuot holidays, which is derived from a group of songs often referred to as the ‘cycle of Moses’ due to their focus on the biblical and post-biblical legends pertaining to his life, including the Exodus from Egypt, the receiving of the Ten Commandments, and the arrival of the Israelites to the land of Canaan. Geographically, our song is found throughout the Mediterranean, from the Straits of Gibraltar to Istanbul and is known by various names, usually “Las tablas de la Ley” (The tablets of the Law) or, after its opening words, “Nuestro Señor Eloheinu” (Our Lord, our God).

However, as we shall see below, “Nuestro Señor Eloheinu” is not always sung in Judeo-Spanish, nor is it always sung with the same stanzas or melody. In some contexts it may be referred to as a piyyut, whereas in other cases it might be categorized as a copla within the Judeo-Spanish repertoire. The complex chain of transmission connecting this song to various corners of the Mediterranean leads to a diverse collection of variants. Despite this, a number of common textual and contextual traits, and in some cases melodic commonalities, unite the sources examined in this article. We will evaluate these common traits and distinctive qualities among a wide range of sources, both written and recorded, in order to gain a broader picture of our song’s use throughout the Mediterranean and the former Ottoman Empire.

The findings here are drawn from Edwin Seroussi’s extensive published article in Spanish, Nuestro Señor Elohenu/Adonay hu Elohenu: Memoria viva y muerta en una canción sefardí del ciclo de Moisés, appear in a volume dedicated to the writer and scholar of Spanish and Sephardic literature, Paloma Díaz Mas.

Maftirim, “Adonay hu elohenu”

Our first example is a source from Istanbul. Here we encounter our song as a piyyut, with a Hebrew text, titled “Adonay hu elohenu” (The Lord is our God). It is fair to note that this Hebrew title is identical in meaning to the Judeo-Spanish title, “Nuestro Señor Eloheinu” mentioned above. “Adonay hu elohenu” was sung in Istanbul among the Maftirim, a choral brotherhood consisting of locals as well as refugees and immigrants of Ottoman cities (especially Edirne and Izmir) displaced to the Turkish capital by wars of the 1910’s. They would gather in synagogues during evening rituals on winter Saturdays to sing from a collection of piyyutim divided in sections according to the different Turkish makams (musical modes), titled Shirei Israel be-eretz ha-qedem (Songs of Israel in the Land of the Orient; SHIBA), published in 1921 by bookseller Benjamin Yosef. Our song “Adonai hu elohenu” appears in this collection under makam Shehnaz. Singing in an Ottoman Turkish style, the Maftirim have maintained their oral tradition of choral singing until the present day. As a result, we have an example that has survived in a contemporary performative context. Here is a recording of “Adonay hu eloheinu” as sung by the Maftirim:

Maftirim: Türk-Sefarad Sinagog Ilahileri/Turkish Sephardic Synagogue Hymns. Istanbul: Gözlem Gazetcilik Basin ve Yayin, Ottoman-Turkish Sephardic Culture Research Center, 2009. (Book, 5 CDs and DVD)

The piyyut recounts the biblical event of Moses receiving the Ten Commandments from God on Mount Sinai. The textual form consists of eight stanzas structured in estrofas zejelescas, a strophic form with a rhyme scheme of aaab. Verses are octosyllabic and heptasyllabic, and the final verse of each stanza ends with the same word, “Anoji,” a biblical form of “I” which is highly significant, as it is the first word of the Ten Commandments.

Stanza 1, “Adonay hu elohenu,” SHIBA

ה׳ הוא אלהינו

נתן לנו את תורתנו

על ידי משה רבנו

שמתחיל באנכי

English Translation

The Lord is our God

gave us our Torah

through Moshe Rabeinu [Moses]

that begins with ‘Anoji’

Below we will examine how, and to what extent, this piyyut sung in Turkey is connected to the Judeo-Spanish repertoire and other sources throughout the Mediterranean.

Northern Italy and “Las tablas de la Ley”

Two cities in Northern Italy functioned as a hub for the wide distribution of our song as early as the first half of the 18th century: Venice, with its history of Hebrew printing presses and trade; and the Western port city of Livorno, which by the late 17th century was another important trade center in the Mediterranean with a large Sephardic population. There are a great number of important sources emanating out of Northern Italy and the surrounding region. Below we will highlight only a few.

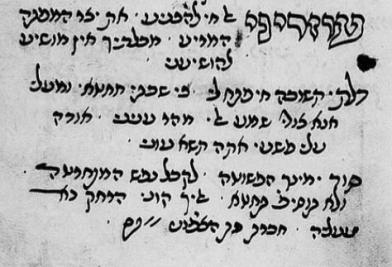

One significant early publication is derived from a collection of Hebrew and Judeo-Spanish songs found in a manuscript dated 1702 by Moshe Bekhar Hacohen, the hazzan of the Levantine community of Venice in the 18th century, originating from Sarajevo (British Library, Ms. Add. 27206). This version was published by Moshe Attias in 1961. Within the manuscript, our song is given the title “Rast Sabuot,” an interesting title for two reasons. First of all, the reference to makam Rast places this version in the realm of Turkish music. Secondly, the title clearly delineates its performative purpose, connecting it to the celebration of receiving the Torah on Shavuot.

Furthermore, there is significant evidence to affirm that in the first half of the 18th century, Las tablas de la Ley circulated in Venice as a uniform version of five stanzas due to the fact that Moshe Bekhar Hacohen’s version from 1702 (or later) is nearly identical, with the exception of minor spelling differences, to another manuscript from Venice titled Et hazamir, dated 1744, published by Moritz Steinschneider in 1858 (Berlin - Staatsbibliothek [Preussicher Kulturbesitz] Or. Oct. 353, fols. 15b-16a).

Shir Emunim

Another important Judeo-Spanish source for our song is Shir Emunim, published in Amsterdam in 1793. A study conducted by Herman Salomon (1970) concluded that although published in Amsterdam, the piece was not necessarily connected to the performance practices of the local Jewish-Portuguese community. To the contrary, Salomon’s study of our song within Shir Emunim lead him to conclude that “it is a song originating in Venice, that by way of Livorno arrived to Gibraltar and to Tetuán where it became one of the most famous Judeo-Spanish songs of the cycle of Moses.”

This version of “Nuestro señor eloheinu” consists of five stanzas. Four of these stanzas are almost a literal translation of strophes 2-5 of the piyyut “Adonay hu elohenu” from Istanbul. Below we will compare a common stanza of these two texts:

“Adonay hu elohenu,” SHIBA, Stanza 2

משה עלה לשמים

בלי אכילה ומים

הביא הלוחות שנים

ובהם כתוב אנכי

Nuestro Señor Eloheinu,” Shir emunim, Stanza 1'

משה עלה לשמיים

סין אכילה אי סין מים

טרוחו לאס לוחות שניים

קי אמפייסאן קון אנוכי

(Judeo-Spanish words in Shir Emunim, above, are highlighted in bold)

English translation of above stanzas

Moses ascended to the skies

Without food or water

He brought back the Tablets of the Law

And on them is written Anoji [SHIBA] / That begin with Anoji [Shir emunim]

In this comparison, we see that both texts are similar thematically, structurally and linguistically. They both recount the ascent of Moses on Mount Sinai, “without food or water,” (v. 2) to receive the Ten Commandments. Both consist of estrofas zejelescas (aaab form), with octosyllabic or heptasyllabic verses, and the final verse in both versions concludes with the word, “Anoji.” Moreover, the opening line, “Moshe ‘alah la’shamayyim,” is exactly the same, in Hebrew in both versions.

In fact, what is interesting about the Judeo-Spanish text is how Hebraized it is. In the above example, the relatively few Judeo-Spanish words used in the version from Shir Emunim are highlighted in bold, including, among others, the use of the Spanish preposition sin (without; סין) instead of the Hebrew bli (without; בלי) in verse two, and in the final line the Judeo-Spanish que empiezan con (that begins with; קי אמפייסאן קון) is used rather than the Hebrew “ubahem katuv” (and on them was written; ובהם כתוב) as a segway to the final returning word in both versions, “Anoji.” The unusual amount of Hebrew used in this Judeo-Spanish version could be attributed to the fact that it recounts a biblical story, or due to its performative function of being sung on holidays such as Passover and Shavuot. It can be noted that this version strongly resembles a piyyut, both according to its conventional performative context and due to the copious use of Hebrew, blurring the boundaries between the Hebrew piyyut and the Judeo-Spanish copla.

Another Hebrew Text, “Yarad el hay al har Sinai”

To further demonstrate this song’s tendency to blur the boundaries between piyyut and traditional categories of the Judeo-Spanish repertoire, we will examine another interesting source compiled by the hazzan David ben Abraham Meldola (c. 1685-1745), who would eventually become a central figure in the Livorno rabbinate. Meldola’s source is titled Seder zemanim, which appears as an appendix to one of the oldest sources available related to our song, a prayer book titled Seder Tefilot Lehodashim ul’mo’adim (Order of prayers for the New Moon and Festivals) published by Joseph Gabbay Villareal in Florence, 1715. This appendix of entries, “composed or arranged for every occasion…” by Meldola, includes piyyutim and other non-canonical religious texts that could be integrated into the liturgy upon the discretion of the cantor.

The liturgical function and melody of the majority of the songs within Seder zemanim are designated in the titles. In folio 344a, a piyyut that opens “Yarad el hay al har Sinai” (The living God descended from Mount Sinai) is designated to be sung “to the melody of Nuestro Señor.” The title also indicates that the piyyut is designated for ‘hotza’at sefer Tora le-sabu’ot’ (‘The removal of the Torah scrolls [from the sacred ark for the festival] of Shavuot’).

Through this source, we learn that a version of “Nuestro Señor Eloheinu” was circulating within the Italian Sephardic communities as early as the beginning of the 18th century, and perhaps earlier. It could be that Meldola was familiar with cantor Moshe Bekhar Hachohen’s version from Venice, one of the first sources we addressed.

“Yarad el hay” as found in Seder zemanim displays the close interaction between Hebrew and Judeo-Spanish texts among the Sephardic communities of Northern Italy. The Hebrew song in Seder zemanim is similar in form to both the Maftirim text (SHIBA) and other Judeo-Spanish texts, primarily due to its use of the estrofas zejelescas (aaab rhyme scheme), octosyllabic or heptasyllabic verses, and the returning word, “Anoji” at the end of each stanza. However the Hebrew in Meldola’s version, despite being connected to the holiday of Shavuot and to the receiving of the Torah on Mount Sinai, is not a Hebrew version closely related to “Nuestro Señor Elohenu” as the Maftirim version is, but rather is a totally separate Hebrew text of didactic nature concerning the Ten Commandments that is sung to the melody of our song.

Here is a transcription and recorded example of “Yarad el hay” recorded by Leo Levy and sung by Italian cantor Simon Sacerdote of Livorno (first 33 seconds of recording only):

“Yarad el hay” sung by Simon Sacerdote of Livorno (first 33 seconds only), recorded by Leo Levy in 1959. YC 00182, National Library of Israel.

The Straits of Gibraltar and Tetuán

The final stop on our journey will be in North Africa, in the Straits of Gibraltar and Tetuán region, where we find a much longer version of our song, a new performative context and a wealth of informants that have been recorded since the 1950’s. In terms of performance, the song is still connected to Shavuot, however it has been removed from the liturgical context common to the Italian versions. Instead, according to the testimony of Rabbi Abraham Benhamu of Tetuán, it is sung in the home during Shavuot dinner festivities, or in the beit midrash study hall at the end of the all-night learning vigil performed on Shavuot eve, known as the tikkun leil Shavu’ot.

The earliest written source of “Las tablas de la Ley” from North Africa is a manuscript from Abraham Israel of Gibraltar (dated between 1761-1770; Díaz Mas and Sánchez Pérez 2013, no. 55). This manuscript, as well as another important manuscript from the Strait of Gibraltar area by Shlomo ben Moshe Tov Elem dated in 1825 (National Library of Israel, Ms no. 3716, fol. 16.a), reveal a version which is much longer than its Italian counterpart, containing fifteen strophes which clearly maintain the same zejelesca rhyme scheme (aaab), versification and the final word “Anoji” with which we are familiar. Both manuscripts mentioned above also share fourteen strophes in common, in the same order. While eight of these stanzas coincide with the versions from Venice, Livorno, and the Ottoman Empire, the rest of the stanzas are concerned with the restoration of the Temple in Jerusalem and of the Messianic era. Two of these North-African Messianic strophes actually correspond to the Maftirim version, further complicating our understanding of our song’s origin.

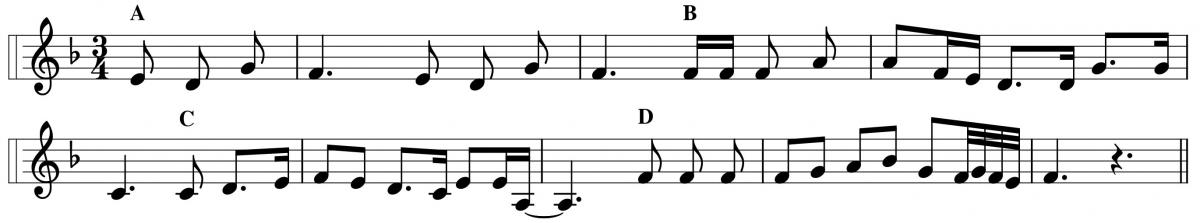

A wealth of field recordings have been conducted from North African informants since the 1950’s. Below we will compare a few variants connected to a melody for our song that is common to all versions from this region.

“Nuestro Señor” Recorded by Henrietta Yurchenko in Tetuán, Morocco, 1956. Sung by Alicia Benassayag de Bendayan. From of the album: “Ballads, wedding songs, and piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Morocco,” Track 09, Folkways Records, 1983.

This relatively early recording from Tetuán (1956), recorded by Henrietta Yurchenko and sung by Alicia Benassayag de Bendayan, displays a version with a high level of embellishment. However, when compared to the two less-ornamented melodies below, we find that all variants share a common structure of four musical phrases of relatively equal length, with similar melodic contour and cadential patterns.

“Mose subió a los shamayim” Recorded by Susana Weich Shahak in 1984, Ashdod. Sung by Sultana Bengio. YC 02287, National Library of Israel.

This variant, recorded by Susana Weich Shahak in 1984 in Ashdod, begins with the lyric “Mose subió a los shamayim,” (Moses ascended into the skies) reminiscent of the opening verse of Shir emunim stanza 1/SHIBA stanza 2 (“Moshe ‘alah la-shamayyim') which we analyzed earlier, as it is a direct translation, containing the substitution of the Judeo-Spanish verb subió (rose) and the preposition + article, a los (to the, pl. because in Hebrew the word denotes “skies”) instead of their Hebrew counterparts. In comparison to the version recorded by Yurchenko, we see a common thread between these two variants of a flatted third scale degree (A-flat), which as a stand-alone case could be excused as an ornament or accident. However both versions employ this same flatted note at around the same location in the melody, between measures 1-3, suggesting that this note may be part of the pattern of transmission.

Nuestro Señor. Gimol Bentolila; גימול בנטולילה. Field recording conducted by Kol Israel in 1981. CD 04733, National Library of Israel

This final variant sung by Gimol Bentolila from 1981 contains a similar melodic contour to the two variants above, but without the use of the flatted third scale degree. This example, due to its simplicity, is interesting when placed side by side with the version of “Yarad el hay,” the piyyut from Northern Italy. Both the North African and the North Italian versions are clearly related on the bases of melodic contour and cadential structure, allowing us to conclude that a common melody was transmitted between North Africa and Northern Italy, and that both differ from the Ottoman version we examined.

Conclusion

We have witnessed how a common text, and in some cases a common melody, has worked its way through a diverse array of Sephardic communities, each singing a version that is slightly different, but all centered around the figure of Moses and in most cases the Shavuot holiday. The boundaries between piyyut and copla genres were tested, as we observed the close interaction between the Hebrew and Judeo-Spanish versions of our song in terms of textual content and performative function. Regarding which version came first: this is difficult to determine. There is a wealth of sources related to this song that are not mentioned here, but are addressed by Seroussi in his forthcoming Spanish-language article which illuminate theories regarding the origin and transmission of the song for Shavuot, “Nuestro Señor Eloheinu.”