Isaac Eliyahu Navon was born in Adrianpole (today Edirne) on May 17, 1859. His father, Rabbi Eliyahu Navon, was one of the Jewish intellectuals and public figures in Adrianpole, a city which had, from the seventeenth century until WWI, one of the most prosperous communities of Sephardic Jews in the Ottoman Empire. The scholars of Adrianpole excelled especially in Hebrew poetry and in music, two fields in which Isaac Eliyahu Navon excelled as well.

From an early stage in life, Navon was influenced by the new currents which spread through the big urban centers of the Ottoman Empire in the 1860s: Haskalah (Jewish enlightenment) and Jewish nationalism. Educated Jews from eastern and central Europe who settled in Adrianpole had strong influence upon the local, young, Sephardic scholars. These Ashkenazi intellectuals spread the literature of the Haskalah among the circles of local youth. The Hungarian researcher, Yosef Halevi, one of the pioneers in the research of the Jews of Ethiopia and Yemen and a journalist and a poet, was one of the prominent figures in the circles in which Navon grew up.

These external influences attracted changes in the attitude of Sephardic Jews in Adrianpole toward traditional Jewish costumes and way of thinking. Navon's father, who later was one of the founders of 'Dorshei Lashon Tsion' in Istanbul, took concern that his son will grow up with the Hebrew language. He studied at the school, 'Kol Yisrael Haverim' in Adrianpole, which was one of the first schools established by ‘Dorshei Lashon Tsion.’ Among Navon's educators and friends were the foremost Sephardic intellectuals of the time, people such as Rabbi Baruch Ben Yitzchak Metani (BNYM), and the historian and literature researcher Avraham Danun, who, in 1880, established the company, 'Dorshei Haskallah,' as well as the Bet Midrash for 'advanced' rabbis. These figures acted as role models for Navon.

At the age of 18, Navon moved with his parents to Istanbul. He started working as a secretary and personal assistant of Moshe Bar Natan, a highly respected wealthy man (('גביר'in the Jewish community in Istanbul.

While working with Bar-Natan, Navon began publishing articles and notes in the Jewish newspapers of Istanbul- Il Tiempo and Il Telegrafo. His articles dealt with urgent issues of the day. At the same time, he began publishing his poems in these newspapers. His writing skills and his broad education, manifest in his articles and poems, drew the attention of Nahum Sokolov, who appointed him to be the Turkish reporter of the important Jewish newspapers of Eastern Europe- Hatsfira and Ha'asif. In these newspapers, Navon published reviews of the Jewish community in Istanbul, addressing various aspects of the community. He reviewed the many disputes which occurred in this community during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries between the conservative and liberal branches, regarding the distribution of authority and resources within the community.

The Navon family household in Istanbul gradually became a point of pilgrimage for important Jewish figures that came from Europe and were on their way to Palestine, or vice versa. As a result of this, Navon became personally acquainted with some of the prominent leaders of the Zionist movement: Herzl, Wolfson, Oshiskin and Zabotinsky. An interesting anecdote recounts the wedding ceremony of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, which was held in the Navon household. The connection between Navon and Ben-Yehuda increased when Navon worked towards acquiring a permit from the Ottoman authorities to publish Ben-Yehuda's newpaper, Hatsvi, in which Navon published a few notes of his own.

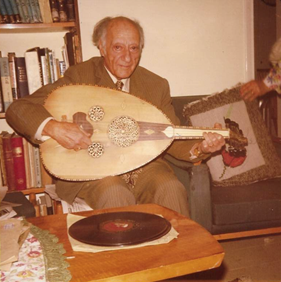

Navon was an active poet and singer all of his life, and dedicated much of his time to these activities. Navon’s poetic endeavors involved both writing his own poems with or without a melody and editing and translating poems of others.

Navon wrote poetry in two genres: 1. poems of reprove and criticism which were related to his public work and community affairs; 2. lyrical, secular poems (about love and nature) or with religious content (for example, dreams of redemption). His style combined elements of different and sometimes contradictory resources. At the heart of his style are the patterns of religious piyyutim of the Jews of Turkey, created in the seventeenth century onwards: quadrangular strophic forms (with rhyme schemes of AABB, AAAB or AABA), syllabic-phonetic meters and quotations of the Jewish holy and literary resources combined with phrases inspired by Turkish poetry. In these archaic forms, Navon combined contemporary themes and language idioms taken from modern Hebrew poetry. He also wrote religious poems which imitate Turkish secular poems, a practice of his predecessors. Navon elaborated this practice, however he wasn't satisfied with merely copying the introduction of the foreign poem, as was common, but insisted on finding a Hebrew parallel for every Turkish word.

Another of Navon’s important contributions was the editing and publishing of ancient piyyutim of old Turkish poets, especially those of Adrianpole. This activity was initiated by the publisher Binyamin Becher in Istanbul, who recruited Navon to this important project, which culminated with the book, Shirei Yisrael Be'eretz Hakedem, which was published in 1921.

In addition to editing, Navon also published Ladino translations of piyyutim and prayers. The goal of these translations was to bring these texts closer to those parts of the community which could not read Hebrew.

Navon's knowledge in ancient and modern poetry came from his natural talents as a singer and from the knowledge he acquired as an active member in the 'Maftirim' choir in Adrianpole and later in Istanbul. Navon was the driving force behind the reestablishment of the 'Maftirim' fraternity in Adrianpole and Istanbul after WWI.

In the spring of 1929, during his seventieth year, and after losing his eyesight, Navon fulfilled his lifelong dream: to settle in Palestine. He settled in Jerusalem and committed himself to music and poetry. He invested most of his time and fortune in the publishing of his songbook Yinon (Jerusalem, 1932). According to Moshe David Ga'on, Navon was also occupied with research of the music of the Sephardic Jews:

'He committed himself to his expertise, gathering the folk eastern melodies, which included almost forgotten ancient Romances. He handed over to Dr. M. Zandberg, and Mr. M. S. Gashuri a big collection of about 50 of these songs and melodies, transcribed in printed musical notation. After some time, he became acquainted with the people of this profession. It is important to add that Rabbi Yitzchak Navon had a pleasant voice and for many years was one of the leaders of the 'Maftirim' choirs in Istanbul. Through this practice he acquired expertise and is considered today as one of a few talented professionals. Navon owns treasures in his lonely house in Jerusalem, this city of many writers, some of which are his past colleagues. He organized a group of important young artists and teaches at night, without expectation of a reward. Among his prominent students are the cantors Yosef Sikron and Shmuel Alkalai, both Jerusalem natives.'

Many years later, Ga'on published another biographical note about Navon, adding:

'He excelled in his pleasant voice, and for many years presided as one of the leaders of the 'Maftirim' choirs in Istanbul. He was considered as one of the few talented professionals, who gathered relics of treasures of sounds and melodies. Among his students were the young singers Yitzhak Levi, Bracha Tsefira, Nachum Nardi, Yosef Sikron, Shmuel Alkalai and others… He was 'Naim Zemiroth Yisrael', from youth to old age.'

Judging by the long list of musicians who were in contact with Navon in Israel, it can be said that he was a main vessel in bringing Judeo- Turkish musical traditions to Eretz-Yisrael and that he had great influence on the formation of the Hebrew folksong (zemer ivri) during its formation. This contribution did not receive sufficient recognition, as Moshe David Gaon notes:

'Usually his activities weren't well appreciated. Many used his works without giving him the credit, and his melodies could be heard on every corner, but without mention of the place they came from. He was blind for the last thirty years of his life. Who, than, will claim the honor he deserves and do him justice… The general Sephardic public which especially enjoyed his music, didn't remember him while he was still alive, in the corner of his silent desolate room, how will they recall him at his death?'

In the last years of his life, Navon settled in Tel Aviv. The lonely old man continued writing poems and songs and used to send them to his friends and colleagues, asking them to find a place to publish them. Despite his age, he continued to sing in his pleasant voice for his visitors, until his death on the eve of Rosh Hashana in 1952, when he was 93. Prior to his death, Navon received payment from his friend Yitzhak Levi, who published the songbook Yona Homia- songs of Yitzhak Eliyahu Navon in 1950, at the Cultural Center by the Histadrut. The book contains songs that were either written, composed, or sung by Yitzhak Eliyahu Navon.

This biography is an excerpt from Edwin Seroussi's article: Miturgama Liyerushalaym: Y.A. Navon Vetrumato Lazemer Ha'ivri (From Turgama to Jerusalem: Y.A. Navon and his contribution to the Hebrew Folksong).