Origins and Canonization of “Fog al-Nakhal” (فوق إلنا خل / فوق النخل)

“Fog al-Nakhal,” is nowadays one of the most popular songs in the Middle East. It is a muwwashshah, “girdle” song, a traditional strophic Arabic form characterized by its refrain between the stanzas. Usually recognized as Iraqi, “Fog al-Nakhal” also appears in the repertoire of several Middle Eastern communities and nations. In the context of the Iraqi Maqam (al-maqam al-Iraqi), this catchy song in maqam hijaz functions as a pasté, a pre-composed light song set to a fixed meter, normally appearing as the culmination of a long improvisatory piece consisting of several sections without clear beat. The easily recognizable pasté often invites group participation in live performances.

Unlike its relatively simple form, “Fog al-Nakhal’s” history is complex, revealing a number of interrelated musical and textual settings. Looking into the information available in order to reconstruct its history, one can see how “Fog al-Nakhal” was canonized as a popular Arab song through the disbursement of commercial recordings. In addition, it is possible to trace how different communities adapted the song to facilitate its use within their communities. Moreover, each community constructed its own narrative about the song in order to foster a sense of belonging.

The conversation regarding the meaning of the title, “Fog al-Nakhal,” is ongoing. Some understand the title to mean “above the palm tree,' while others insist upon, “I have a friend up there,” two expressions in Arabic that sound highly similar, pronounced differently according to grammatical rules of dropping consonant sounds. The phrase, “above the palm tree” is a common Iraqi expression evoking a positive state of being, used frequently as an optimistic reply to the question, “How are you?” The prevalence of the expression and the equal prevalence of the popular song are often linked. On the other hand, “I have a friend up there” fits more appropriately with the theme of the text. The lyrics are sung from the perspective of a lover who looks above to the moon and the evening sky, singing of the pains of unrequited love.

From online blogs to scholarly sources, the song’s authorship is attributed to a number of different composers, such as the prominent Iraqi-Jewish musician Salah al-Kuwaity (1908-1986), and in some cases it is cited as anonymous (Shohat 2015: 32; Murad 2003: 15-17). According to Iraqi music scholar Scheherezade Qassim Hassan, the melody is attributed to Sufi poet and composer Mullah Uthman al-Musili (1854-1923) a blind prodigy and orphan from age seven onward, who traveled as a child from Mosul to Baghdad to study Iraqi maqam from the greatest singers of his time. [1] In this context, the melody currently associated with “Fog al-Nakhal” was sung to the text of al-Musili’s sacred hymn, 'Fog al 'arsh fog, mi'raj abu Ibrahim” (Upon the throne), performed during mawlid sessions - birth celebration rituals of the Prophet [See Appendix: Texts, “Fog al ‘arsh”]. See below a contemporary performance of al-Musili's 'Fog al 'arsh' (فوق العرش):

'Fog al 'arsh,' Mustafa al-Zubaidy

The song as it is more-or-less known today was popularized by the famous Iraqi singer Nazem al-Ghazali (1921-1963), released between 1947-1954. Ghazali’s version included the above-mentioned secularized text concerning unrequited love, attributed to Juburi al-Najjar [See Appendix: Texts, “Fog al-Nakhal,” N. Ghazali]. The musical arrangement is attributed to Nazem Naim and Jamil Bashir, producers known for re-arranging pre-existing Iraqi folk songs for radio and television broadcast.[2] Ghazali’s vocal style and ornamentations set a precedent upon which future versions of the song were based. The canonization effect of this popular recording supports Charles Seeger’s theory regarding the impact of technology on oral tradition (Seeger 1966: 159-161). Furthermore, this canonization is apparent when comparing post-Ghazali recordings that are highly similar to one another to “Balini-b balwa,” the variant of the song that may have been the one less affected by Ghazali’s performance.

'Fog al-Nakhal,' Nazem al-Ghazali

Sabah Fakhri: “Fog al-Nakhal” in Syria

“Fog al Nakhal” became just as prominent in Syria as it did in Iraq, if not more. The fame of Ghazali’s version in Syria was fostered by television broadcasts and recordings, especially those by the charismatic Syrian singer Sabah Fakhri. [3] Born in Aleppo in 1933, Fakhri has contributed to the revival of Syrian folk music in a career spanning over fifty years. He is recognized for his mastery of maqam and as a tarab performer — tarab meaning “a musically induced state of ecstasy” that relies on a performer’s state of musical inspiration and immersion within a given maqam, or saltanah, and also upon meaningful performer-listener interactions, among other components (Racy 2003: 6, 41, 120).

The tarab style can be understood through Fakhri’s live performance of “Fog al Nakhal,” which reflects Fakhri’s immersion within the maqam (saltanah), of “feeling haunted by the tonic pitch,” immersing himself and the audience with the richness of maqam (Ibid. 120). Unlike many versions of “Fog al Nakhal” that include alternating solo-chorus passages, Fakhri and his chorus sing simultaneously throughout the song, embellished by his elaborate ornamentations that stress qarar-ghammaz relations, like a drone [See Appendix: Melodic Variants (S. Fakhri) mm. 1-2.]. His version is also distinct due to its elaborated instrumental introduction performed by a large firqah (almost two minutes in length, the same amount of time as the song itself), in which Fakhri faces his ensemble and acts as conductor. The lights of the venue illuminate the audience, allowing for direct interaction between him and his listeners. Through the tarab style, Fakhri connects deeply with the maqam, the ensemble, and the audience simultaneously.

'Fog al-Nakhal,' Sabah Fakhri

Fog al-Nakhal (فوق النخل) in Jewish Communities

“Balini-b Balwa,”(بالين بلوة) a Melodic Variant of “Fog al-Nakhal” from Bombay

Among the Jewish community of Baghdad, the melody of “Fog al-Nakhal” was also known as “Balini-b balwa,” a version featured prominently in the work of Sara Manasseh, who conducted research on the expatriate Iraqi Jewish community of Bombay, India. “Balini-b balwa” shares common textual relationships with Juburi al-Najjar’s “Fog al-Nakhal,' and shares structural relationships with the melody of “Fog al-Nakhal,” explored below.

Manasseh conducted field recordings of Jewish immigrants from Baghdad to Bombay, including Jacob Baher in 1984, who moved to Bombay from Baghdad as a young man in 1932. She also received a field recording of the mother of classical composer Brian Elias, who moved to Bombay in 1926 as a teenager. [4] Elias claims that as a child his mother would sing him this song “as a lullaby,” and features the melody in his composition, L’Eylah (premiered in BBC Proms in 1984) in a solo viola. [5] The text used for Manasseh’s album, performed by the group Rivers of Babylon, is based off of the recording of Elias’s mother.[6] Manasseh also claims to have discovered another Jewish family from Bombay who sang this melody to the religious Hebrew text, “Ki eshmerah Shabbat,” a song intended for the afternoon of the Sabbath. The last example provides a snapshot into a single family that integrated the melody of “Fog al-Nakhal”/ “Balini-b balwa” into its private religious repertoire (Manasseh 2012: 132-133).

'Balini b-balwa', Jacob Baher

Melodic relations between “Fog al-Nakhal” (فوق النخل) / “Balini-b balwa” (بالين بلوة)

Due to the fact that Manasseh’s interlocutors left Baghdad before the release of Ghazali’s recording, and due to their familiarity with a version of “Balini-b balwa” from as early as the 1920’s in Baghdad, it could be that this strand in the evolution of “Fog al-Nakhal” melody was less impacted by Ghazali’s popular version. “Balini-b balwa” is structurally similar enough to other post-Ghazali melodies to be defined as a variant of “Fog al-Nakhal.” Despite its simpler, more skeletal melodic and rhythmic structure, it still contains sufficient similarities in melodic contour to be grouped together with the remainder of the variants of “Fog al-Nakhal' (see Example 1 below). Textually, multiple stanzas are shared between “Fog al-Nakhal” and “Balini-b balwa,” with the common phrase, “walla marida ya’eni, balini-b balwa” overall correlating melodically and textually with Ghazali's version (compare mm. 5-8 in Example 1).

Example 1: Melodic Variants Analysis of “Fog al-Nakhal;” “Fog al’Arsh;” “Balini-b Balwa”

Nonetheless, there are some notable differences between “Balini-b Balwa” and the other variants. The Bombay variant does not include some melismatic motives that are nearly identical in the other versions, causing the resolution note at the ends of cadences to differ from post-Ghazali versions (Example 1: compare mm. 4 and 8 in each transcription). This marked difference provides the listener with a contrasting impression of tonal center and cadence structure. In addition, the form differs between “Balini-b Balwa” and the other Ghazali-influenced melodies. While all recordings of “Fog al-Nakhal” repeat section A at least once before transitioning to section B, “Balini-b Balwa” does not repeat the A section, leading to a strophic AB form rather than AAB.

Though it is unclear to what extent Ghazali may or may not have impacted the variant from Bombay, it is apparent that “Balini-b Balwa” evolved on a different trajectory than the other variants analyzed here. As mentioned previously, due to its derivation in 1920s Baghdad and due to processes of migration, this variant could have bypassed the canonization process underwent by the other versions.

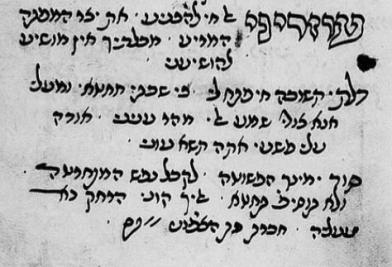

The Piyyut “Kum Am Nachal” (קום עם נחל)

In 1998, Israel-born Syrian cantor-composer Menachem Mustacchi of the Syrian Jewish community of Brooklyn published a pizmonim book titled Shirah Hadasha (1998) in collaboration with Uri Amram. This book includes Hebrew poems created through the process of contrafactum: converting mundane songs in various languages to religious songs in the long tradition of paytanim starting with R. Israel Najara (c. 1550-1625). Mustacchi included in Shirah Hadasha Hebrew piyyutim set to contemporary popular Arab melodies, including “Fog al-Nakhal,” reworked as “Kum Am Nachal” (Rise, People of the Inheritance), which he recorded along with David Shiro, another famous cantor of the Syrian community in Brooklyn.[7]. Following his predecessors, Mustacchi created a phonetic resonance between his Hebrew poem “Kum Am Nachal” and “Fog al-Nakhal.” In the printed piyut, the song is indicated to be sung in 'maqam hijaz [...] To the melody of: Fog al-Nakhal,' once again reinforcing the popularity of this Arabic folksong within the community.'[8]

Mustacchi wrote “Kum Am Nachal” between 1991-1994 in Brooklyn, during the First Intifada in Israel and the Gulf War. He claims to have written the piyyut “to strengthen the people” in light of the conflict in the Middle East. [9] Mustacchi’s Biblically-inspired text is a rallying cry to the people of Israel to look eastward to “strengthen the desired land of [their] fathers” in supplication to God for redemption (ge’ula). The text focuses on a return from exile to the Promised Land, with the final stanza claiming, “The sons of the people [of Israel] will return. / Together, [to] His temple, His temple” [See Appendix: Texts, “Kum Am Nachal”].

Mustacchi’s Hebrew lyrics offer the opportunity to sing a very familiar and beloved Arabic melody set to a text oriented specifically to the interests of the Jewish community. This type of new Hebrew songs are intended for haflot (parties) and weddings, among other social events in which “Fog al-Nakhal” could likely have been sung in the past.

'Kum Am Nachal,' David Shiro and Menachem Mustacchi

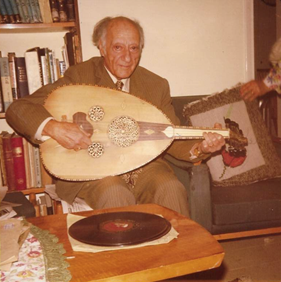

Dudu Tassa and the Kuwaity’s: A Search for Belonging

Popular Israeli musician Dudu Tassa is the grandson of Daoud Al-Kuwaity, who was a prominent oud musician in Baghdad alongside his brother Salah Al-Kuwaity. As mentioned previously, the Kuwaity brothers have often been attributed with composing “Fog al-Nakhal” during the period that they were performing as popular musicians in Baghdad (1930s-1940s). In a 2020 interview, Dudu Tassa attributes authorship of the song to Nazem al-Ghazali, though he acknowledges that his grandfather and brother played this song. [10]

Tassa currently performs “Fog al-Nakhal” within a retrospective repertoire honoring his grandfather’s musical tradition. This includes a number of compositions attributed to the Kuwaity brothers, whose legacy has been erased from the Iraqi soundscape after the Jews of Baghdad were disenfranchised and forced to move from Baghdad to Israel in the early 1950’s. The Kuwaity brothers arrived in Israel in 1951, where their music was largely disregarded, with limited opportunities to perform and record (Warkov 1987: 9, 109; Dori 2021).

Tassa’s performance blends the traditional Iraqi rendition of the song by the Kuwaitys with his own contemporary pop-rock style. In contrast to Mustacchi’s Hebrew piyyut, Tassa sings “Fog al-Nakhal” in its original Arabic version, retaining the basic melodic structure and text of Ghazali’s version. Tassa’s ensemble integrates a qanun within a rock ensemble consisting of electronic instruments and a drum set. The song is performed with added funky rhythms and electronic effects. Through this process of elaboration of a traditional song, Tassa reclaims a heritage that is highly personal and familial as well as communal, preserving the sounds of the Iraqi Jewish diaspora.

'Fog al-Nachal' Dudu Tassa and the Kuwaitys

Conclusion

In the course of its dispersion, “Fog al-Nakhal” has maintained its recognizable musical structure while simultaneously undergoing musical and textual adaptations catering to different ethnic groups, religions, families, and individuals sharing a common heritage and in search for a sense of belonging. The song marks a shared space that cut across national frontiers and political tensions.

It would be interesting to find and analyze more pre-Ghazali/Sabah Fahri recordings, including those of al-Musili's 'Fog al-Arsh' and the Iraqi Jewish song “Balini-b balwa.' Since Ghazali’s version more-or-less canonized “Fog al-Nakhal”’s melodic contour, there is a high likelihood that a study of earlier variants will further illuminate the pre-history of this much beloved folksong.

Endnotes

[1] Hassan, Scheherazade-Qassim, interviewed by Courtney Blue. May 29, 2017. This is additionally supported by Al-Salchi, “Mulla Uthman al-Musili.” Iraqi Maqam; as well as Bernard Moussali in 'Music from far away and long ago,' AMAR Foundation. Date Accessed: 10 April 2022.

[2] Hassan, Scheherezade Qassim, interviewed by Courtney Blue. Date: May 29, 2017.

[3] Bali, Salim. “Fog Elna Khel [!] (Salamu aleikum).” Account of Syrian-American composer’s exposure to Ghazali on a TV show that aired in Damascus in 1966. Publishing Date Unknown. Date Accessed: 10 April 2022. http://www.dycom-il.com/f/fog-elna-khel-info.html

[4] Manasseh, Sara. Personal Interview June 5, 2017 with Courtney Blue.

[5] Duchen, Jessica. “Composer Brian Elias, Making Music With Meaning.” The JC. 13 April, 2017. Date Accessed: 10 April 2022. https://www.thejc.com/culture/music/composer-brian-elias-music-1.436356

[6] Rivers of Babylon. “Ki Eshmerah Shabbath/ Balini-b-Balwa.” CD: Rivers of Babylon: Live in India. Track 103. Smithsonian Folkways. A.R.C.E., 2005.

[7] See the Hebrew text and recordings in https://www.pizmonim.org/book.php#509v. Accessed 10 April 2022. See also Tiferet Ha-Piyut. “Naim Zemirot Israel ha-Hazan ve-ha-Paytan R. David Shiro Kum Am Nachal.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqAHe5fWFC4. Accessed: 10 April, 2022.

[8] ibid. See Hebrew notes indicating maqam and melody at the top of the page: https://www.pizmonim.org/book.php#509v

[9] Mustacchi, Menachem. Phone interview, June 5, 2017 with Courtney Blue.

[10] Full interview with Dudu Tassa regarding this project, including the recording of Fog Al-Nakhal in particular: Gluckin, Zvi. 'Dudu Tassa Embraces the Al-Kuwaitys,' The Ingathering. 4 August, 2020. Date Accessed: 1 May 2022. https://theingathering.substack.com/p/dudu-tassa-embraces-the-al-kuwaiti...

Bibliography

Bali, Salim. “Fog Elna Khel [!] (Salamu Aleikum).” Publishing Date Unknown. Date Accessed: 17 May 2017. http://www.dycom-il.com/f/fog-elna-khel-info.html

Brough, Michael W. “Translating Trust in Iraq, one Arabic Greeting at a Time.” LA Times. Date Accessed: May 17, 2017. http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-0301-brough-iraqi-interpreter...

Dori, Dafna, 2021. The Brothers Al-Kuwaity and the Iraqi Song 1930-1950. Ph.D. diss. Uppsala Universitet, Institutionen för Musikvetenskap.

Duchen, Jessica. “Composer Brian Elias, Making Music with Meaning.” April 13, 2017. The JC. Date Accessed: 10 June 2017. https://www.thejc.com/culture/music/composer-brian-elias-music-1.436356

Gluckin, Zvi. 'Dudu Tassa Embraces the Al-Kuwaitys,' The Ingathering. 4 August, 2020. Date Accessed: 1 May 2022. https://theingathering.substack.com/p/dudu-tassa-embraces-the-al-kuwaiti...

Holden, Stacy E. A Documentary History of Modern Iraq. University Press of Florida: Gainesville, 2012.

Menasseh, Sara. Shbahoth — Songs of Praise in the Babylonian Jewish Tradition: Routledge, 2012.

Murad, Ezra. Shirei am be-lahag ha-bedui ha-Iraqi meturgamim le-Ivrit. Jerusalem, 2003.

Racy, Ali Jihad. Making Music in the Arab World: The Culture and Artistry of Tarab. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Rivers of Babylon. “Ki Eshmerah Shabbath/ Balini-b-Balwa.” CD: Rivers of Babylon: Live in India. Track 103. Smithsonian Folkways. A.R.C.E., 2005.

Seeger, Charles. “Versions and Variants of the Tunes of “Barbara Allen.” AFS L54, 1966.

Shohat, Ella. “The Question of Judeo-Arabic.” Opening Essay for Arab Studies Journal, Vol. XXIII No. 1 (Fall 2015): 32.

Warkov, Esther. The Urban Arabic Repertoire of Jewish Professional Musicians in Iraq and Israel: Instrumental Improvisation and Culture Change. PhD Dissertation. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1987.