Biography by Pasquale Troia

Choirmaster of the Tempio Maggiore (Great Synagogue) in Rome from 1948 to 1984, Elio Piatelli enhanced the liturgical life of the synagogue (and beyond) with a choir that sang melodies from the oral traditions of the various rites of the Roman Jewish community as well as original compositions for holidays and festivals. Graduated cum laude in Literature from the University of Rome in 1931, he pursued his innate musicality studying in Rome with Maestro Cesare Dobici (1873-1944) and graduating with a diploma in composition from the Conservatory Santa Cecilia of Rome in 1941. On that same year, he participated in the competition of the Royal Philharmonic Academy of Rome with two works for choir. In the post-war period he was director of the choir of the Politeama Theater of Palermo, Sicily. He taught courses in Hebrew liturgical chant in Italy (Rome, Palestrina, Turin, Milan, Florence, Naples ...) and France (Sénanque abbey near Avignon, Saint-Louis in Paris, Strasbourg). The following is a first attempt to locate, catalog and analyze his musical compositions and other of his scholarly interests (as documented in his personal library. One can distinguish at least four specific areas of activity by Piatelli during his long career: (1) transcriptions of oral traditions; (2) composition; (3) public and literary activities; (4) musicological activities.

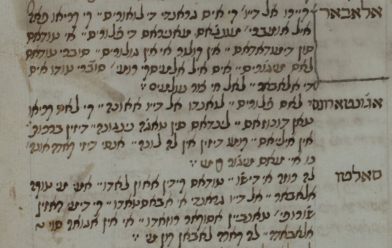

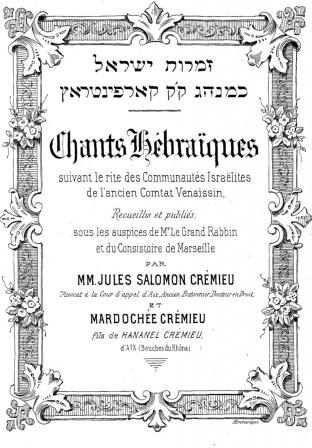

(1) Until the last years of his life, Piatelli was engaged in the transcription of the oral traditions of cantors from the various Italian Jewish rites and traditions. Piattelli transcribed not only out of the concern that these traditions may disappear with the death of their live witnesses, but above all to allow young cantors to learn those traditional songs and thus enhance the cultural, liturgical and musical heritage of the Italian Jewish communities. He transliterated the Hebrew texts of the songs in Latin characters with a very simple method that takes into account the modern Sephardi pronunciation of Hebrew practiced in Israel. He also translated the texts into Italian and commented them in Italian and English. He dedicated his works “to the unknown authors of the melodies.” The chants in his transcriptions are arranged following the Jewish liturgical calendar. Their melodic structure indexes the diverse Jewish liturgical festivals and on events of the Jewish calendar. He began his collection of chants in 1967, notating the living oral voices of various Italian locations and rites: Rome (Italian, Sephardi), Piedmont (Apam, Italian, Ashkenazi), Florence (Sephardic), and northeastern Italy (Italian, Sephardi, Ashkenazi). This ethnographic activity produced four publications:

• Canti liturgici ebraici di rito italiano (Liturgical Jewish Chants of the Italian Rite), transcribed and commented by E. Piattelli Edizioni De Santis, Rome 1967;

• Canti liturgici ebraici del Piemonte (Jewish Liturgical Chants from Piedmont), transcribed and commented by E. Piattelli, Edizioni De Santis, Rome 1986;

• Canti liturgici di rito spagnolo del Tempio Israelitico di Firenze (Liturgical Chants of the Sephardic Rite of the Israelite Temple in Florence), transcribed and commented by E. Piattelli, Editrice La Giuntina, Florence 1992;

• Canti liturgici ebraici di rito spagnolo di Roma (Jewish Liturgical Chants of the Sephardi Rite of Rome) transcribed by Elio Piattelli (edited by P. Troìa), Fondazione Istituto Italiano per la Storia della Musica, Rome 2003-5763.

Despite the commitment and passionate research on the part of Maestro Piattelli and the appearance of these four collections in print, still many of his musical transcriptions remained unpublished. However, he was never discouraged. Until the last days of his life, he used every possible opportunity to document more melodies and make everyone aware of the value of the immense musical and liturgical heritage of the Italian Jewish communities. Hopefully, the Maestro's wish of 'saving these songs from the silence and destruction that follows any loss of memory of the oral tradition to which these melodies have been entrusted for so many centuries' will still be realized. In 1969, in collaboration with the Italian ethnomusicologist Giorgio Nataletti (1907-1972),

Piatelli recorded one hundred and fifty Roman Jewish liturgical songs. He wrote that these melodies are 'of particular scientific interest, not only for the completeness of the investigation, for the excellence of the performances and for the goodness of the recording but also because it is a disappearing tradition...' (Yearbook of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia, 1970, pp. 106-107). This collection is kept at the Bibliomediateca of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia (http://www.icbsa.it/Etnomusica/mobile/index.html#p=14). Prof. Walter Brunetto prepared a preliminary cataloging of this collection, but it is still necessary to identify the liturgical songs and contextualize them within the order of prayers for festivals and holidays according to the Roman rite. This is a work in progress, and will published by Walter Brunetto and Pasquale Troìa at the Squilibri Editore in Rome (https://www.squilibri.it/ ) in the framework of the AEM series (Archives of Ethnomusicology, National Academy of Santa Cecilia).

(2) Composing new liturgical melodies was a means to renew the meaning and value of the Jewish liturgical traditions. There are hundreds of compositions by Piatelli mainly for four voices with transliterated Hebrew texts (sometimes bringing the vernacular version of the text, but not setting it to the music). The melodies are mostly set to the Book of Psalms, whether to entire texts or to selected verses. Through these compositions, the choirmaster could continue the tradition of other masters and cantors of the past and at the same time to renew the repertoire with contemporary sounds. Their style, their melodic 'flavor', in their simplicity and linearity (which facilitates and favors everyone’s singing) highlight a profound liturgical inspiration. They are not foreign to the spirit of the synagogue. This remarkable heritage of original compositions by Maestro Piattelli still lies in manuscripts and is rather unknown. Other songs by him live in the memory of those who sang them at the Tempio Maggiore in Rome.

Some of his compositions appeared in five CDs. Three are by the Ha-Kol Choir: (1) Canti liturgici ebraici [2000]: Mizmôr shirû la'Adōnāy shîr chādāsh (Ps. 98); Sionide on a famous poetic text by Jehudah Halevi (Songs of Zion, in I. Zemora, R. Jehudah Halevi, Tel Aviv 1964, volume III, p. 57). (2) Canti di Scola Tempio [2006]: Hashkîvēnû, Îmlōk ... bachûrîm, Bārûk habba (Ps. 118: 26-29). (3) Chatan ve Kallah. Il matrimonio ebraico a Roma [2010]: Bārûk habba (Ps. 118: 26-29), Maskîl shîr iedîdōth (Ps. 45:1-3, 9-10). Two CDs are by the Shiré Miqdash Ensemble conducted by R. Adolfo Locci: (1) I canti del Tempio da Roma a Padova [2016]: Mizmôr leDāwid. ’Adōnāy mî-yāgûr be’āholekā (Ps.15); (2) I canti del Tempio ... e diverranno un unico essere [2019]: Bārûk habba (Ps. 118: 26-29); Maskîl shîr iedîdōth (Ps. 45: 1-3, 9-10). In 1979, EDIPAN Music Editions of Rome released the LP Canti liturgici ebraici di rito italiano featuring the voice of Rav Alberto Funro. This production included thirty rarely heard arrangements of liturgical songs by Piatelli.

In 1982 he composed Eikh nafal, halal lo betokh hammilhama [How the victim fell, not in the midst of the war] in memory of Stefano Taché [Gay], the two-year-old boy “killed by murderous hands motivated by anti-Semitic hatred after praying in front of the Temple on 9 October 1982, Sheminì Atzeret 5743' (terrorist attack which also injured another forty people). In the large square in front of the main entrance of the Tempio Maggiore there is a memorial plaque dedicated to Stefano Taché.

Other compositions by Piatelli include settings from the Bible: Exodus III, 8; four-part songs on the first Hebrew verses of the Song of Songs (113 pages of music, unfinished); Song of Songs IV, 11-13; five compositions on Lamentations for four voices (145 pages of music); Job 3, Job 4: 13-21; Isaiah 12 and 11 (for 4 voices), Isaiah 35 and 42, and then Isaiah 1,2-9, 2,2-7, 25,1-8, 32, 40,9-11, 42 part II from v. 8, 55, 60, 61, 66: 10-14; Jeremiah 30, 31; 21 pages of music on Micah 4, 1-13 for four voices; a first act (incomplete?) with four scenes on a libretto inspired by the biblical story of Judith; Ecclesiastes 4; and many other compositions to be cataloged. He also wrote compositions for various liturgical texts and modern Hebrew poetry. Already in 1937 he published, 'Enèyha (Your eyes) for voice and piano set to a poem by Haim Nachman Bialik [1873-1934] (De Santis edition, Rome).

In 1941 he composed the opera in four acts, Inés de Suaréz (by Alonso de Morroy, with libretto by G. Guerra): it was performed in Santiago de Chile on the occasion of the fourth centenary of the founding of the city. So he writes to his mother: 'M[aestro] Gai very kindly examined the main scenes of 'Inés', praising me very much and affirming that I am a “good melodist, good harmonist, and good counterpoint [writer], [however] he added that the orchestration was, in some places, a little loaded. But to remove something can always be done in due time, in the case of a performance.” His other compositions based on texts by European authors: Quattro liriche sul testo di Schiller, Quattro momenti poetici per Soli e Orchestra (Gauthier, Ex-voto, (soprano), Baudelaire: De Profundis (basso), Baudelaire: L’Horloge (soprano), Arnaud “Sur deux noirs chevaux” (basso)). Inni e poesie liturgiche for choir and organ; Poesia biblica, polifonie for four-vice choir; Liriche per voce e pianoforte su testi italiani, francesi, inglesi ed ebraici; Liriche per voce e orchestra su testi italiani, francesi, inglesi ed ebraici. A lullaby (Ranen yeled ra’anan) for Ranen Minsky. It should also be noted that even his more secular compositions also draw inspiration from Jewish and Jewish themes. For example his String Quartet (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P7-bSF39qiE ) is subtitled “based on motifs of liturgical melodies from the Italian Jewish rite.”

(3) To understand Piatteli’s overall contributions, it is essential to mention also his activities as a scholar, in particular as a translator. His knowledge of Hebrew and European languages (many still remember him as a teacher of English) were crucial in this context. He combined inspiring didactic experiences with creativity as when on an old sheet of music he composed for voice alone without words (and for piano indicated but not written) 'My heart in the Highlands' and writes “composed after explaining the English song at the post-war Jewish high school (5 students)!” Some of his compositions for four voices, for choir, and for voice and piano are inspired by authors of English literature (such as, Eight Hebrew Melodies by Byron; Death by John Donne), Italian (Cavalcanti, Petrarca, Machiavelli [from Mandragola], Sacchetti, Carducci), French (Ballade des dames du temps jadis by F. Villon), medieval Hebrew (Yehudah Halevi and “A poem by Shemuél Ha-naggid,” in La Rassegna Mensile di Israel, XXXIII-5 [1967], 179-181) and modern Hebrew(Esther Ben-Ezer [Raab], Bialik), and other authors such as AM Carèdio, N. Nardi, Drazin. He translated from Latin (Vita Adae et Evae, in the Annuario di studi ebraici, Italian Rabbinical College, Rome 1968-69); from the French (La farsa della tinozza, Fussi-Sansoni editions, Florence 1953; A. De La Halle, La commedia di Robin e Maria (edited by E. Piatelli), Fussi-Sansoni editions, Florence 1959; A. De Lamartine, “Cristoforo Colombo”. He also wrote The legend of the seven sleepers of Ephesus, in whose initial page he stresses that “it is not a translation but an original work of mine” (source: Germanic History [in Latin, Monumenta Germaniae Historica]), written as a radio drama, recorded and broadcast on Vatican Radio. Numerous manuscripts of his lectures are waiting to be published.

Piatelli was particularly commitment to the Jewish-Christian dialogue as shown by his participation in the foundation of the Radici series, and his translations of André Neher, L’essenza del profetismo (Marietti, Casale Monferrato, 1984), Il pozzo dell’esilio (Marietti, Genoa, 1990), Chiavi per l’ebraismo (“Keys to Judaism,” Marietti, Genoa 1998), and of the series Il ponte translated by Leon Klenicki, Geoffrey Wigoder [ed.], Concise Dictionary of Jewish-Christian Dialogue (Marietti, Genoa, 1988), the kabbalistic work Seven sanctuaries (Tea, Milan, 1990) and Armand Abécassis, La lumiére dans la pensée juive (Berg International, Paris 1988, not published in Italian).

(4) Piatelli did not consider himself a musicologist, but as a musician, a composer who “must be a musicologist” to engage with these liturgical melodies. But some of his works are definitely musicological in nature. He edited works by A. Banchieri, Vivezze di Flora e Primavera (Rome, 1967) and La barca di Venezia per Padova (Rome, 1969); Giaches de Ponte, Le 50 stanze del Bembo, in collaboration with L. Bianchi (Rome, 1981-82). On the occasion of the Music and Bible conference organized by Biblia (Siena 24-26 August 1990), he was persuaded to comment on the melodies on the Hebrew texts of some songs still valued today in the liturgical festivals by the Jewish community of Rome, in particular at the Tempio Maggiore (published in P. Troia (ed.), La Musica e la Bible, Proceedings of the International Study Conference promoted by Biblia and the Chigiana Academy of Music, Garamond, Rome 1992, pp. 349-380).

All these musical, literary and musicological works are kept in forty-four binders that make up the Piattelli Fund at the IBIMUS in Rome (https://ibimus.eu/tour). This Fund was established thanks to the initiative of Prof. Giancarlo Rostirolla, the passionate interest of Maestro Lino Bianchi (1920-2013), the donation of Maestro Piattelli’s daughter, Dr. Daniela Piattelli, and the preliminary cataloging work carried out by myself.

I personally enjoyed Maestro Piatelli’s affectionate friendship for over twenty years, I considered him a master of rare exemplarity. Unfortunately, I saw him without disciples who could “take advantage” of his more and his availability. Observing his isolation, especially in his last years, I thought several times that the choristers must have considered him quite (or too?) demanding, while academics did not find him aligned with the criteria ruling their professional work. It is the duty of everyone, and not only of the Italian and Roman Jewish communities, to promote a complete cataloging of the works by Maestro Piattelli and to make the rich and variegated legacy that he left behind known to anyone who wants to “colligere fragmenta, ne pereant” (“collect the fragments, lest they be lost”).

May his memory be a blessing to all of us.

Sources:

Giacomo Baroffio, Pasquale Troia, “Elio Piattelli in memoriam,” Rivista Liturgica LXXXVIII, Terza serie, n° 5 settembre-ottobre 2001, 669-677.

Pasquale Troia, Canti del Tempio Maggiore di Roma, tomo II, Gangemi Editore, Roma (forthcoming)

Elio Piattelli: A memory and testimony of in the twentieth anniversary of his death: https://www.shalom.it/blog/editoriali-bc9/il-ma-elio-piattelli-un-ricord...