Although the song Hatikvah became the emblematic lyrical signifier of Zionism, other contemporary songs of Hatikvah contented for that spot in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Today these songs are only remembered by a small hardcore of old Hebrew songs’ enthusiasts.

Dort wo die Zeder was one of those celebrated and widespread early Zionist anthems, as it emerges from the historical evidence about its contexts of performance immediately after it was conceived in the early 1880s.[1] The hymn-like quality of this song and the status it acquired exemplify the mechanisms through which Jewish modernity articulated itself on the basis of German aesthetics, in this case poetic and musical. Dort wo die Zeder also shows how the Zionist movement engaged song and communal singing practices as a primary means for disseminating its ethos, echoing patterns of German cultural activism, particularly at the level of youth movements. Dort wo die Zeder has been profusely printed with and without musical notation and distributed orally since its original publication. Indeed the amazing speed with which Dort wo die Zeder spread throughout Jewish (and as we shall see also non-Jewish) spaces as an icon of the Zionist spirit also deserves special attention. This song profoundly permeated German-Jewish memory and survived (mostly in Germany), on a subterranean level, until the present.

Text

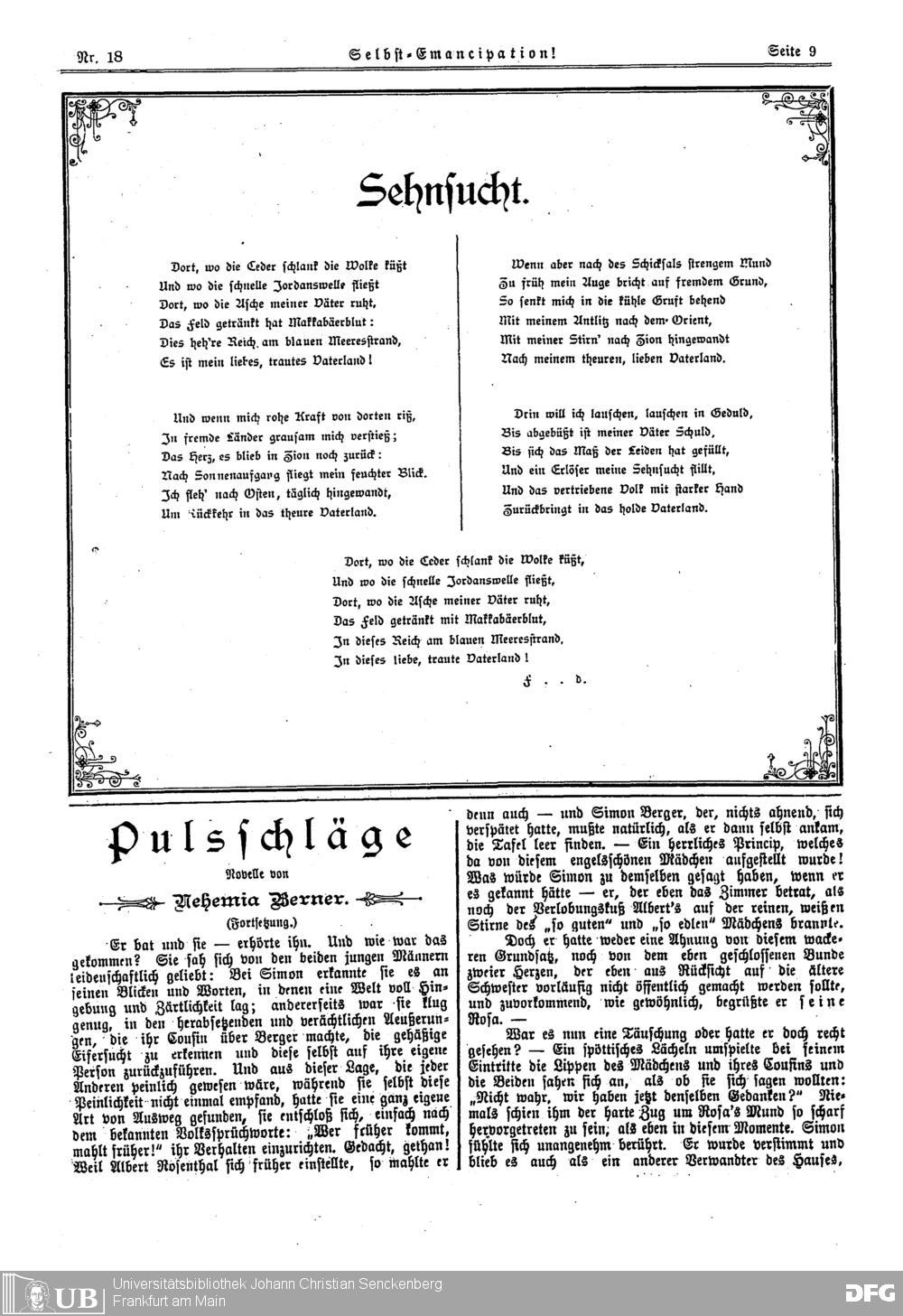

The author of the poem, Dr. Itzhak Feld (1862-1922), was a German-speaking Jewish poet and lawyer born in Lvov (Lemberg) and a member of the Hovevei Zion movement in Galicia. His song was first printed in 1885 in Selbst-Emancipation (no. 19, 16/8/1885, p. 9), a pioneer Zionist journal edited by the Zionist leader and Yiddishist Nathan Birnbaum. Titled ‘Sehnsucht,’ the poem is cryptically signed by “F..d” (i.e. Feld). There is copious evidence about its performance in Zionist assemblies throughout Europe since at least 1894 as well as among the Jewish settlers in Palestine around the same time. It was also recorded commercially early in the twentieth-century. Various attributions of poetic and musical authorship, sometimes contradictory, rendered the song a mythic aura that is commonly associated with folksongs.

Dort wo die Zeder consists of four stanzas of six lines each in the rhyme pattern AABBCC -- and the last word of each stanza is “Vaterland.” The first stanza is repeated at the end with minor variations in the last two lines. The word “Zeder” in the opening line is printed in the original version as “Ceder,” a peculiar spelling that will pervade in several later editions of the song. One cannot also fail to notice that the same title, ‘Sehnsucht,’ was given to the earliest published musical version of Hatikvah (published by Cantor S. T. Friedland from Breslau/Wroclaw in 1895). The close link between these two seminal national Jewish songs remained a strong onw throughout the first three decades of the twentieth century. This is the version of Dort wo die Zeder as published in 1885:

Dort, wo die Ceder schlank die Wolke küßt,

und wo die schnelle Jordanswelle fließt,

dort, wo die Asche meiner Väter ruht,

das Feld getränkt hat Makkabäerblut —

dies heh’re Reich am blauen Meeresstrand,

es ist mein liebes, trautes Vaterland!

Und wenn mich rohe Kraft von dorten riß,

in fremde Länder grausam mich verstieß:

Das Herz, es blieb in Zion doch zurück,

nach Sonnenaufgang fliegt mein feuchter Blick,

ich fleh’, nach Osten täglich hingewandt,

um Rückkehr in das theure Vaterland.

Wenn aber nach des Schicksals strengem Mund

Zu früh mein Auge bricht auf fremdem Grund,

So senkt mich in die kühle Grust behend.

Mit meinen Antlitz nach dem Orient

Mit meiner Stirn’ nach Zion hingewandt

Nach meinem theuren, lieben Vaterland.

Dort will ich lauschen, lauschen in Geduld,

Bis abgebüβt ist meiner Väter Schuld,

Bis sich das Maβ der Leiden hat gefüllt,

Und die Erlöser meine Sehnsucht stillt,

Und das vertriebene Volk mit starker Hand.

Züruckbring in das Vaterland.

Dort, wo die Ceder schlank die Wolke küßt,

und wo die schnelle Jordanswelle fließt,

dort, wo die Asche meiner Väter ruht,

das Feld getränkt hat Makkabäerblut —

In dieses heh’re Reich am blauen Meeresstrand,

In dieses liebes, trautes Vaterland!

Hebrew and Yiddish translations

Dort wo die Zeder was soon translated into Yiddish as well as into Hebrew in several versions, most of them on shortened versions, omitting a few stanzas. The following translations were taken from ‘Zemereshet’ (Heb. זֶמֶרֶשֶׁת), a website dedicated to the collection and preservation of songs that were written and performed in the Hebrew language from the beginning of the Zionist movement up to establishment of the state of Israel.

|

שָׁם בִּמְקוֹם אֲרָזִים שָׁם בִּמְקוֹם אֲרָזִים מְנַשְּׁקִים עָבֵי רוֹם,

|

דאָרט וווּ די צעדער דאָרט וווּ די צעדער הויך די וואָלקן קיסט,

|

it was printed in his Shir va-zemer (Warsaw: Tushya, 1903, p. 21). This Hebrew version is still performed in sing-alongs in Israel. A sheet music arrangement of Dort wo die Zeder by the famous cantor and composer Asher Perlzweig (1870-1942) of the Vine Court Synagogue in the East End of London includes under the music both the original German text (without crediting its author) as well as Libushitzky’s Hebrew translation in Ashkenazi pronunciation.[2]

it was printed in his Shir va-zemer (Warsaw: Tushya, 1903, p. 21). This Hebrew version is still performed in sing-alongs in Israel. A sheet music arrangement of Dort wo die Zeder by the famous cantor and composer Asher Perlzweig (1870-1942) of the Vine Court Synagogue in the East End of London includes under the music both the original German text (without crediting its author) as well as Libushitzky’s Hebrew translation in Ashkenazi pronunciation.[2]The earliest Hebrew translation however was apparently the one by A. A. Pompiansky (1835-1893), titled Makom sham Arazim. This translation follows the German original closely and considering the year of the translators’ death, it was done just a few years after the appearance of the original German song. It was sung in an evening party organized by the Jewish student organization of the University of Basel during the Second Zionist Congress of 1898[3] and it was also widespread in the Jewish settlements of Ottoman Palestine in the first decade of the twentieth century. The other translations into Hebrew are by Haim Arieh Hazan (titled Eretz hemdatenu) first published in Mivhar shirei tziyyon (Warsaw: Hazomir, 1917; titled: ‘Eretz hemdati’) without the authorization of the author as stated in the authorized version included in his collection Neginot (Vilnus 1920/1, pp. 47-8); and the one by the writer, journalist and translator Pesah Kaplan (1870-1943), titled Bimkom ha-erez.

It seems that at in the early stages of oral transmission the original German song was “Yiddishized” rather than translated into Yiddish when it was sung by Yiddish speakers (for example changing ‘küßt’ with ‘kißt’ in the first line). A formal Yiddish translation by “Rev. M. I. Broyda” appears a bit later in the important early American collection of Zionist and Jewish songs, Shirei Tziyon ve Shirei-Am of 1909.[4]

It seems that at in the early stages of oral transmission the original German song was “Yiddishized” rather than translated into Yiddish when it was sung by Yiddish speakers (for example changing ‘küßt’ with ‘kißt’ in the first line). A formal Yiddish translation by “Rev. M. I. Broyda” appears a bit later in the important early American collection of Zionist and Jewish songs, Shirei Tziyon ve Shirei-Am of 1909.[4]

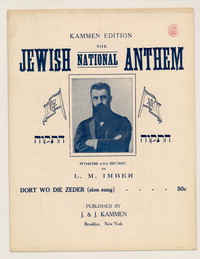

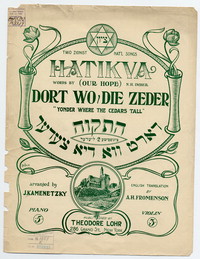

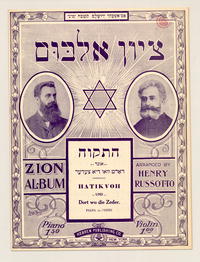

Sometimes, the song is wrongly attributed to other authors or to misprints of the name of Dr. Itzhak Feld. He appears  as “J. Feld” in a later, amended edition of the song included in a collection edited by Alfred Nossig[5] as well as Leo Feld in an often quoted episode from the First Zionism Congress of 1897 (see also below).[6] In other cases the fame of being the writer of such a canonic song is appropriated by or attributed to other writers named “Feld” such as Mordechai Ehrenpreis Feld in an article on the Zionist movement in Stryj/Stryi (in Western Ukraine).[7] More interesting however is the attribution of Dort wo die Zeder to Naftali Herz Imber, the author of Hatikvah.[8] Dort wo die Zeder indeed appears frequently in sheet music editions and other song collections in tandem with Hatikvah and this fact, coupled with the similarity between the songs may be the source of this confusion in the attribution.

as “J. Feld” in a later, amended edition of the song included in a collection edited by Alfred Nossig[5] as well as Leo Feld in an often quoted episode from the First Zionism Congress of 1897 (see also below).[6] In other cases the fame of being the writer of such a canonic song is appropriated by or attributed to other writers named “Feld” such as Mordechai Ehrenpreis Feld in an article on the Zionist movement in Stryj/Stryi (in Western Ukraine).[7] More interesting however is the attribution of Dort wo die Zeder to Naftali Herz Imber, the author of Hatikvah.[8] Dort wo die Zeder indeed appears frequently in sheet music editions and other song collections in tandem with Hatikvah and this fact, coupled with the similarity between the songs may be the source of this confusion in the attribution.

The intertwined fate of Dort wo die Zeder and Hatikva finds echoes in yet another interesting source. Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, the “father” of Jewish music research, noted a certain family resemblance between the tunes of both songs in a comparative table that he included in volume 4 of his Thesaurus[9]. Idelsohn remarks there that Dort wo die Zeder is a “25-year old Zionist song” and stresses the coincidental similitude in the melodic contour of the songs that at the time he wrote his work (before 1923) still shared the title of anthem of the Zionist movement.

The tune of Dort wo die Zeder

The song appears for the first time with musical information in the earliest Zionist songster, the Liederbuch für jüdische Vereine edited by Heinrich Loewe in 1894/510]. The melody is defined as ‘Jüdische Volksmelodie’ but is also attributed to ‘Oestermann.’ In a footnote there is an additional reference to another melody by “Berth. W. Conti.” We can suggest that Berthold W. Conti is the pseudonym of Dr. Berthold Kohn, born in 1868 in Horazdovice (today Czech Republic). His version, dedicated to the “Kadimah” student organization in Vienna, was published in a rare, undated sheet music.[11] Conti’s melody, in the style of a march with a wide range of dramatic falling and rising broken chords, incidentally recalls Pierre De Geyter’s tune for the left-wing anthem, “L'Internationale”.

The song appears for the first time with musical information in the earliest Zionist songster, the Liederbuch für jüdische Vereine edited by Heinrich Loewe in 1894/510]. The melody is defined as ‘Jüdische Volksmelodie’ but is also attributed to ‘Oestermann.’ In a footnote there is an additional reference to another melody by “Berth. W. Conti.” We can suggest that Berthold W. Conti is the pseudonym of Dr. Berthold Kohn, born in 1868 in Horazdovice (today Czech Republic). His version, dedicated to the “Kadimah” student organization in Vienna, was published in a rare, undated sheet music.[11] Conti’s melody, in the style of a march with a wide range of dramatic falling and rising broken chords, incidentally recalls Pierre De Geyter’s tune for the left-wing anthem, “L'Internationale”.

The simple melody in 4/4 meter consists of four isorythmic phrases of four bars each in the form ABCC1. Each phrase is divided into two motifs of two bars each. A clear and simple harmonic progression is embedded in the melody. The most dramatic melodic move occurs in the second phrase that opens with an arpeggio in the range of an octave of the second inversion of the chord on the third degree of the minor scale (parallel major). The last phrase repeats in the ouvert-clos pattern (V-I). In short, this is a quintessential European folk melody of the type that can be found in many Jewish repertoires, liturgical and domestic, and that could as well be borrowed from the surrounding non-Jewish cultures.

The song is reprinted with music in the important collection of songs for German-Jewish youth and gymnastic Jewish organizations edited in 1911 by the cantor and composer Jacob Beimel.[12]

This version is noticeable as a transcription from oral tradition, underscored by its melodic and textual divergences from most of the other published versions. For example Beimel’s version differs from the most common version in measures 3-4 in that they are a third higher, probably a remnant of the common oral practice of doubling the melody by a third. A few years later it was also published with music in the songster of the German Zionist youth movement Blau-Weiss. These publications attest to the popularity of the song among members of a younger generation of Zionist who were otherwise far removed from the earlier ideals and pathos of the Hovevei Zion movement out of which Dort wo die Zeder originated.

In most editions of Dort wo die Zeder the melody is defined as “traditional” or “folk”. Yet, in his recent master thesis, Messner brings new evidence from the unpublished memoire by Heinrich Loewe titled Auf dem Weg nach Zion – Sichronoth[13] that includes the following remark: “Gesungen wurde es [Dort wo die Zeder] laut zur Melodie einer Variation des traditionellen Lecha Dodi”.[14] Although we could not locate for the moment a version of this “original” liturgical melody, we can discern a certain structural affinity between ‘Lecha dodi and Dort wo die Zeder if one takes into consideration the repetition of the refrain after each stanza in the Hebrew song.

Early Commercial Recordings

As many other favorite Jewish songs Dort wo die Zeder was recorded commercially at an early stage. The earliest recording of Dort wo die Zeder located so far is the one by Leon Kalisch (born in 1882), a member of the “Jüdischen Theaters in Lemberg” that was active in Vienna.[15] It was produced in Germany, circa 1910, by the Beka Company, no. 16258 (on the other side is, no surprise, “HaTikwa”). In this recording the song is performed in Yiddish.

A second recording, this time in Hebrew translation, was issued by Cantor Abraham Jassen (1882-1963) accompanied by violin, cello and piano. It was recorded in 1917 for the Columbia Phonogram Co. label in New York City, plate no. E3617.

Reception

Soon after it was published, Dort wo die Zeder became a favorite item in Zionist gatherings. Its inclusion in Heinrich Loewe’s anthology further hammered down its communal status as an anthem. However, the showing of favor that Theodor Herzl expressed in public towards this “Nationallied” during the first Zionist Congress in Basel was the gesture that sealed its undisputed reputation in the Zionist lyrical canon. As attested by a “live” report from the grounds of the congress in the Allgemeine Schwezerische Zeitung as quoted a few days later in the Berliner Vereinsbote of September 10, 1897, Herzl favored this Zionist song over others. According to this account, a moving performance of the song by the cantor of the Jewish community in Basel, Sigmund Drujan-Bollag, took place during a party held after the formal deliberations (there is no mention in which language the song was sung). Following the performance Herzl suggested considering Dort wo die Zeder as the Zionist anthem and his proposal was met with a thunderous applause.[16]

Soon after it was published, Dort wo die Zeder became a favorite item in Zionist gatherings. Its inclusion in Heinrich Loewe’s anthology further hammered down its communal status as an anthem. However, the showing of favor that Theodor Herzl expressed in public towards this “Nationallied” during the first Zionist Congress in Basel was the gesture that sealed its undisputed reputation in the Zionist lyrical canon. As attested by a “live” report from the grounds of the congress in the Allgemeine Schwezerische Zeitung as quoted a few days later in the Berliner Vereinsbote of September 10, 1897, Herzl favored this Zionist song over others. According to this account, a moving performance of the song by the cantor of the Jewish community in Basel, Sigmund Drujan-Bollag, took place during a party held after the formal deliberations (there is no mention in which language the song was sung). Following the performance Herzl suggested considering Dort wo die Zeder as the Zionist anthem and his proposal was met with a thunderous applause.[16]

A second scene from the closing session of the same congress reinforces its continuous performance during those faithful days of late August 1897 in Basel. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the first congress, an article in the Berliner Zeitung includes the following description of very last moments of the congress:

“Viele Teilnehmer weinten. Andere fielen sich in die Arme. Dritte drückten sich die Hände und riefen sich in Anlehnung an die bekannte Gebetsformel gegenseitig zu: ‚Nächstes Jahr in Jerusalem‘. Ein jüdischer Studentenchor gab Herzl zum Abschied ein Ständchen und sang das Lied von Leo [sic] Feld ‘Dort wo die Zeder schlank die Wolken küßt...’ Herzl, von Basel nach Wien zurückgekehrt, war zutiefst erschöpft, doch glücklich über das Erreichte. ‚Fasse ich‘, notierte er am 3. September 1897 in sein Tagebuch, den Baseler Congress in ein Wort zusammen das ich mich hüten werde, öffentlich auszusprechen so ist es dieses: In Basel habe ich den Judenstaat gegründet. Wenn ich das heute laut sagte, würde mir ein universelles Gelächter antworten. Vielleicht in 5 Jahren, jedenfalls in 50 wird es jeder einsehen.”[17]

Following this canonization by Herzl, notices in the Jewish Zionist press about the performance of Dort wo die Zeder on different occasions proliferate. Just as an example, the song was performed at the closing of a lavish Hannuka event held in Brăila (Muntenia, eastern Romania), at the local ‘Jüdische Volks-Lessehalle’ on December 19, 1900. The performance was by ‘the Zionist choir’, and in the performance participated also the great Bessarabian cantor Barukh Schorr (1823-1904) with harmonium accompaniment (Die Welt 4/1/1901, p. 11).

The presence of the song in Palestine is almost as contemporary as its European launch. In his memoire of his trip to Palestine, the important German Zionist activist Willy Bambus (1862-1904) reports hearing Dort wo die Zeder during a nightly journey to the Jewish settlement of Gedera in Palestine sung by a group of “Kolonisten”. From this testimony it is not clear if the song was performed in German or Yiddish (or even perhaps in Hebrew). At the end of his description he adds: “Der Gesang weckte zunächst alle Hunde des Dorfes und allmählich kamen auch einige Kolonisten.”[18]

The iconicity of Dort wo die Zeder also transpires in texts stemming from the strong anti-Zionist circles within the German Jewry. Quoting a scene that took place in a Jewish elementary school in Berlin that appeared in the Israelitische Rundschau no. 29 (July 18, 1902, p. 5), the author of an anti-Zionist pamphlet, a certain “Méchanik” (probably a pseudonym) from Mainz states:

“Schon suchen die Zionistischen Agitatoren ihre Propaganda auch auf die Schuljugend auszudehnen wie z.B. in Berlin, wo bei einem Kiderausflug zionistische Reden gehalten und nationaljüdische Lieder Dort wo die Zeder u.s.w. gesungen wurden. Auch eine nationaljüdische Kunst wird liebewoll gepflegt.”

In a footnote to this remark Méchanik adds: “Als die Kinder gefragt wurden, wo denn eingentlich ‘das liebe Vaterland teuren sei’ ertönte (aus 65 Kehlen) ein lautes ‘Jerusalem’ als Antwort.”[19]

Not only in Jewish circles Dort wo die Zeder appears as an iconic lyrical expression of modern Zionist fervor even in the eyes of non-sympathizers. In an article titled ‘Die Versammlung Israels schreitet rüstig vorwärts!’ in Die Stern the periodical of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Days Saints we read:

“Daß wir in der letzten Zeit leben, ist uns Heiligen der letzten Tage nichts Neues; denn sonst hießen wir nicht so… Als eine solche Tatsache wird die Welt in Kürze die Versammlung Israels in Palästina anstaunen, und noch größer wird das Staunen sein, wenn aus dem hohen Norden ein ungekanntes Volk hervortreten wird. Es ist bekannt, daß die Versammlung Israels schon begonnen hat. Das Wort des Paulus (Römer, 11: 25) wird Wahrheit: ‘Blindheit ist Israel zum Teil widerfahren, so lange, bis die Fülle der Heiden eingegangen sei’. Ebenso sagt Jesus voraus (Lukas, 21: 24): ‘Jerusalem wird zertreten werden von den Heiden, bis daß der Heiden Zeit erfüllet wird’. Und nun vollzieht sich in unsrer Zeit vor unseren Augen das merkwürdige, in der Weltgeschichte ohne Beispiel dastehende Ereignis, daß nach zweitausendjähriger Zerstreuung in der Hauptmasse des jüdischen Volkes eine Sehnsucht nach der alten Heimat erwacht. Durch alle Weltteile ergeht der Ruf an die Zerstreuten: ‘Zurück nach Palästina!’ Und zwar wollen sie dort nicht Händler, sondern wie ihre Väter Bauern sein. Sehnsüchtig singen sie: ‘Dort, wo die Zeder schlank die Wolke küßt…’ (Zionistisches Nationallied)”[20]

This stereotypical anti-Semitic view of the Jew as merchant transformed into a worker of the Land thus fulfilling Christian prophecies of redemption complicates these otherwise sympathetic non-Jewish German reactions to Zionism. Notice in this quotation the phrase “sehnsüchtig singen” that catches the essential feeling that the original poem (titled ‘Sehnsucht’) was designed to convey to the readers/singers.

After the Holocaust

World War II brings to an end the millenary Judeo-German relation that reached its full strength during the early twentieth century. Yet, the eclipse of German Jewry during and after World War II was not total. From the ashes of the Holocaust Dort wo die Zeder resurfaces again and again, not in massive Zionist rallies of rowdy meetings of Zionist youth movements as before the war but rather in private and isolated lyrical moments. A document found at the Deutsches Historisches Museum (Inventarnr. DG 70/190) and described as “Handzettel mit einem lyrischen Text zum Unabhängigkeitskampf in Palästina” titled “Palästina-Kundgebung der Berliner VVN [Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes]” includes our song, Dort wo die Zeder, authored by “J. Feld” and reproduced by Harry Schwarzer. The pamphlet is dated 1948 by the VVN in the “Sowjetischer Sektor” of Berlin but its origin is earlier and is related to a young man from Berlin called Harry Schwarzer (b.1923) who apparently distributed this pamphlet. Schwarzer was deported in 1942 to Warsaw and later killed in Auschwitz. His stopelsteiner can be found at Kleine Andreasstraße 8/9, Berlin-Friedrichshain.[21]

At the same time that Harry Schwartz was marched to Auschwitz, the notorious Rumanian-born German-Jewish poet Paul Celan writing from his own Rumanian detention camp under Nazi occupation mentions Dort wo die Zeder in his poem that was eventually titled Schwarze Flocken (1943), one of the many he wrote about his complex, tormenting and hurtful relation with his parents.[22] Dort wo die Zeder appears under the code of Lied von die Zeder and is mentioned as a song that was constantly on the lips of his father. Celan fought the Zionist beliefs of his father and it took decades before he visited the “fatherland” mentioned in the song.

More recently, Dort wo die Zeder resurfaced intermittently in public events held in contemporary Germany marking Jewish or Zionist historical landmarks. For example, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Herzl’s death, a concert was announced as follows:

“Todestag von Theodor Herzl: Anlässlich des 100. Todestages von Theodor Herzl am 3. Juli 2004 laden die Jüdische Gemeinde zu Berlin und die Botschaft des Staates Israel in Verbindung mit der Botschaft der Republik Österreich und der Botschaft der Republik Ungarn zu folgenden Veranstaltungen ein: Sonntag, 27. Juni, 18 Uhr: “Dort, wo die Zeder schlank die Wolke küsst...” Lieder und Texte aus der Frühzeit des Zionismus gesungen und vorgetragen von Mark Aizikovitch und Gästen (Jüdisches Gemeindehaus Berlin, Fasanenstraße 79/80, Großer Saal).[23]

Another touching reappearance of Dort wo die Zeder in the contemporary German soundscape took place around the encounter of two brothers Mayer Menachem and Fred Raymes, who were separated as children during the war and found each other only after more than three decades.[24] A documentary film about their story titled ‘Menachem & Fred’ by the Israeli directors Ofra Tevet and Ronit Kerstner earned a prize at the Berlinale 2009. In a blog about this event we read:

„Die Tränen standen Menachem Mayer, Fred Raymes und deren Partnerinnen Nili Ronen und Lydia Raymes in den Augen, als Musikerinnen der Oberstufe Klezmer-Stücke spielten und der junge Lenderschüler Jakob Häuser (Leitung Ulrich Noss) in der Heimkirche ein jüdisches Volkslied sang. Die Umarmungen mit Häuser und die Begegnungen mit jenen Schülern und Lehrern, die bereits Israel besucht hatten, waren überaus herzlich.”

The caption of the photo accompanying the notice uncovers the name of the anonymous ‘Volkslied’: “Mit dem Lied ‘Dort, wo die Zeder schlank die Wolke küsst’ brachte Jakob Häuser die Kinderzeit von Menachem Mayer und Fred Raymes zum Klingen.”[25]

The archeology of Dort wo die Zeder, of which only a selection of findings was displayed here, uncovers (as if one needed further proofs) the deeply-rooted German-Jewish entanglement. The language and form of the Romantic German poetry is recruited to convey a dramatic cry for national Jewish redemption expressed in Orientalistic brushstrokes. The ashes and blood of Israelite antiquity that are buried in the land of the cedars (which is in fact Lebanon, an extension of Palestine, as was Syria, in the German-Jewish imagination) where the river Jordan flows call to the (German-speaking) Jews to return to the East, to relocate in the mythical homeland and reignite there a sovereign existence that was cut off two millennia ago. Nothing in the content of this song shows any hope for acceptance in an alternative Zion, Germany or the Austro-Hungarian Empire, that so many Germanized Jews around the 1880s saw as their permanent destination. Yet the Judeo-German entrenchment is deeply embedded in the aesthetics of the poetic language. Form, images and sounds (since the song was conceived to be performed aloud) challenge content in this song. And although the melody in minor with its momentary outburst of triumphal major in the second phrase may have originated in the mystical synagogue song announcing the Sabbath, its aesthetics also declare its allegiance to the European soil that produced it.

Finally, one may speculate as to why Hatikvah, a contemporary song of similar literary content, musical mode and melodic contour, eventually prevailed over Dort wo die Zeder as the anthem of the Zionist movement.[26] For the moment it would just be suggested that the Eastern European pedigree of the former song and its being conceived originally in Hebrew rather than German, were decisive factors in that momentous development. The narrow window of opportunity that opened for German culture and language in the late nineteenth century to become a decisive force in the Zionist movement was short lived. Hebrewism in its Eastern European disguise took over the leading role in the Jewish national movement while its German-speaking component remained latent only in translation. This is also the reason why in Palestine/Israel Sham bimkom Arazim overtook the original Dort wo die Zeder.

Bibliography

Elon, Amos: Theodor Herzl: Eine Biographie, Wien/München, 1979.

Felstiner, John/Fliessbach, Holger: Paul Celan: Eine Biographie, 2nd ed. Beck München, 2010.

Meir, Menahem/Raymes, Frederick: Are the Trees in Bloom Over There?: Thoughts and Memories of Two Brothers, Jerusalem, Yad Vashem, 2002.

Messner, Philip: Leo Winz und die Diskurse jüdisch-nationaler Identität um 1900, Magisterarbeit, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Philosophische Fakultät III, Institut für Kultur- und Kunstwissenschaften, Fachbereich Kulturwissenschaft, 2008.

Nemtsov, Jascha: Der Zionismus in der Musik: Jüdische Musik und nationale Idee, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz, 2008.

Nossig, Alfred (ed.): Die Zukunft der Juden: Sammelschrift, Berlin, Lilienthal, 1906.

Perlzweig, Maurice L.: “Asher Perlzweig – A Cantor in Anglo Jewry”, in: Noy, Dov/ Ben-Ami, Isaachar (ed.), Studies in the Cultural Life of the Jews in England (Studies of the Folklore Research Center), vol. 5, 1975, pp. 227-244.

Shahar, Natan: Shir shir ‘aleh na: Toldot hazemer ha-ivri, Tel Aviv, Modan, 2006.

Slouschz, Nahum (ed.): Knesset gedolah o Ha-kongres ha-sheni

[1]The present Song of the Month is extracted from Edwin Seroussi’s recently published essay: Dort wo die Zeder/Ceder: Jewish-German Lyrical Encounters. In: Die Dynamik kulturellen Wandels. Essays und Analysen [Festschrift Reinhard Flender], ed. Jenny Svensson. LIT Verlag Münster, 2013, pp. 55-71.

[2] Dort Wo Die Ceder = [Schom Bimkaum Arozim ...]: Jüdische [sic] Volkslied, London: R. Mazin & Co, c 1915. On Perlzweig see, Maurice L. Perlzweig, “Asher Perlzweig - A Cantor in Anglo Jewry.” In: Studies in the Cultural Life of the Jews in England (Studies of the Folklore Research Center, vol. 5 (1975), edited by Dov Noy and Issachar Ben-Ami, pp. 227-244.

[3] Nahum Slouschz (ed.), Knesset gedolah o Ha-kongres ha-sheni be-bazel, Warsaw 1898, p. 74. (In Hebrew).

[4] Shirei Tziyon ve-Shirei-Am edited and printed by Yosef ben Yehudah Mogilnitski [=Joseph Magil], 8th edition, Philadelphia, 1909, p. 6.

[5] Alfred Nossig (ed.), Die Zukunft der Juden: Sammelschrift, Berlin: Lilienthal, 1906, p. 22. See: http://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/freimann/content/pageview/1056342.

[6] http://www.berliner-zeitung.de/archiv/am-29--august-1897-legte-theodor-herzl-auf-dem-ersten--allgemeinen-zionistencongress--in-basel-den-grundstein-fuer-den-kuenftigen-staat-israel-die-geburtsstunde-eines-traumes,10810590,9324014.html

[8] See: Zion Songs. Popular Hebrew National Songs. Dort Wo Die Zeder. Words and Music by L. [sic] N. Imber. Arr. by A. R. Zagler, published by S. Schenker, 66 Canal St., n.d. A copy is found at Johns Hopkins University, Levy Sheet Music Collection, Box 119, Item 004b. Available online: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/15899.

[9] Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, Gesänge der orientalischen Sefardim. Jerusalem- Berlin- Wien, 1923, p. 116. (Hebräisch-orientalischer Melodieschatz IV).

[10] This important collection is discussed in detail in: Jascha Nemtsov, Der Zionismus in der Musik: Jüdische Musik und nationale Idee. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2008, pp. 353-355.

[11] Berthold W. Conti, Zwei Lieder für Eine Singstimme mit Pianoforte Begleitung, [no. 1]: Dort Wo Die Ceder, op. 21. Berlin: Siegel & Schimmel, 189?.

[12] Jüdische Melodieen [sic], Notenheft zur dritten Auflage des 'Vereinsliederbuchs für Jung-Juda', Berlin: Verlag der Jüdischen Turnerschaft, 1911, p. 11.

[13] Jerusalem, Central Zionist Archive, A146/6, chapter on “Kunst und Kunstler,” p. 7.

[14] Philip Messner, Leo Winz und die Diskurse jüdisch-nationaler Identität um 1900. Magisterarbeit, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Philosophische Fakultät III, Institut für Kultur- und Kunstwissenschaften, Fachbereich Kulturwissenschaft, 2008, p. 57-8, note 215.

[15] On this important Yiddish troupe see, Delphine Bechter, Le théâtre yiddish Gimpel de Lemberg : une Odyssée oubliée. Yod 16 (2011), 83-98. Available at: http://yod.revues.org/659.

[16] Berliner Vereinsbote, no. 43 (September 10, 1897), p. 7.

[17] Julius H. Schoeps, “Die Geburtsstunde eines Traumes,” Berliner Zeitung, 23/8/1997 (http://www.berliner-zeitung.de/archiv/am-29--august-1897-legte-theodor-herzl-auf-dem-ersten--allgemeinen-zionistencongress--in-basel-den-grundstein-fuer-den-kuenftigen-staat-israel-die-geburtsstunde-eines-traumes,10810590,9324014.html; accessed August 8, 2013). This scene is mentioned in Amos Elon, Theodor Herzl: Eine Biographie, Wien; München, 1979, p. 241.

[18] Willy Bambus, Palästina: Land und Leute, Reiseschielderungen, Berlin: Siegfried Cronbach, 1898, p. 93.

[19] Das zionistische Trugbild und seine Gefahr. Mainz: E. Herzog, 1903, p. 8. The occasion was a visit of a ‘Jüdischenationale Frauenvereinigung’ delegation to Berlin’s Jewish elementary schools. The question was asked by ‘Frau Ben-Jehuda aus Jerusalem.’

[20] “Die Versammlung Israels schreitet rüstig vorwärts!” by “Ein j.- Frei w. A. Böhme in einem Lazarett in Leipzig,” Die Stern – Zeitschrift der Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der letzten Tage, vol. 49, no. 2 (1917), p. 18.

[21] http://www.stolpersteine-berlin.de/de/biografie/2355 (Accessed August 28, 2013).

[22] Celan’s song is discussed in detail in: John Felstiner und Holger Fliessbach, Paul Celan: Eine Biographie. 2nd ed. München: Beck, 2010, pp. 43-46.

[23] www.hagalil.com/archiv/2004/06/herzl-berlin.htm (Accessed August 8, 2013).

[24] The story is told in Menahem Meir and Frederick Raymes. Are the Trees in Bloom Over There?: Thoughts and Memories of Two Brothers. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2002, p. 230.

[25] http://erlach.over-blog.de/article-kraft-zu-einem-neuen-leben-59271138.html (Accessed August 8, 2013).

[26] Both songs were printed back to back for many years. See for example: Leo Kopf, Hatikwah: Dort, Wo Die Zeder; Zwei Jüdisch-Nationale Lieder Für eine Singstimme, Klavier und Gitarre. Berlin: Jüdischer Verlag, 1917.