Seroussi, Edwin. "Hatikvah: Conceptions, Receptions and Reflections." Yuval - Studies of the Jewish Music Research Center, vol. IX (2015).

Hatikvah: Conceptions, Receptions and Reflections

Abstract

If you have ever searched for Hatikvah online, you were surely exposed to a barrage of factual and fictional information that, in the Internet Age, circulates virally in diverse variants, dosages and combinations ad nauseam.[c1] These writings and their indiscriminating viral spread tell us more about the speculators and reproducers of these stories than they do about the song’s actual historical past. Untangling these stories behind the story of Hatikvah is the core of this essay. For Hatikvah both is and is not what you think. It does not derive from Smetana nor from a Sephardic prayer. And an early Zionist pioneer did not compose it spontaneously. Nor did it become the national anthem of the State of Israel until very recently.

If you have ever searched for Hatikvah online, you were surely exposed to a barrage of factual and fictional information that, in the Internet Age, circulates virally in diverse variants, dosages and combinations ad nauseam.[1] These writings and their indiscriminating viral spread tell us more about the speculators and reproducers of these stories than they do about the song’s actual historical past. Untangling these stories behind the story of Hatikvah is the core of this essay. For Hatikvah both is and is not what you think. It does not derive from Smetana nor from a Sephardic prayer. And an early Zionist pioneer did not compose it spontaneously. Nor did it become the national anthem of the State of Israel until very recently.

The truth is that Hatikvah (“The Hope”) is a perfect example of the early Zionist movement’s creative drive and haphazard, experimental character. It also exemplifies the elusiveness of the symbols of modern nation-states. From the outset, we note that this is a rare case of bottom-up creativity. A song made its way to consecration by a state that adopted it as its national anthem on a journey involving grass roots energy rather than legislative design. Because of the “folk” origins of its music and the re-writing of Naftali Herz Imber’s poem ‘Tikvatenu’ by its users, attempts at reconstructing the “true origins” of the melody and text of Hatikvah as known in the present have generated a rather dense, one-hundred year old literature on the subject. This quest produced speculative theories that are today obsolete since we know the precise circumstances in which Imber’s poem was shaped and the musical contrafactum (adaption of a preexisting melody to a new text) behind which Hatikvah was conceived.

An immediate trigger for the present essay was the release of a booklet titled Hatikvah: Past, Present, Future: An Interdisciplinary Journey into the National Anthem by the Israeli pianist and music appreciation expert Astrith Baltsan published (with two CDs) by the Ministry of Education of Israel in 2009. This production became part of a wide public campaign by its author, presented as “up-to-date, revolutionary research” on the subject and delivered in live performances to the (un)critical acclaim of the press. This show, which is neither “up-to-date” nor “revolutionary,” runs nowadays as a world tour. Baltsan’s text not only fails to acknowledge many earlier substantial studies on the subject but, in spite of a short discussion of the split reception of Hatikvah in one of its chapters, it offers an overall ideological stance serving a clear nationalist agenda.[2]

However, the present essay’s goal is not necessarily to contest or criticize Baltsan’s narrative but rather to contextualize it within the larger frame of the literary and scholarly narratives about Hatikvah. Therefore, we rely solely on common knowledge previously published and reproduced by a long chain of authors but address this body of data with the tools of critical theory.

Studying Hatikvah shows how a distinct Zionist music culture emerged in Palestine and spread throughout the Jewish world with remarkable speed.It also shows how its practice at ceremonies of Jewish institutions, synagogues, schools and youth movements, as well as its commercial distribution in sheet-music and commercial recordings throughout the European, Middle Eastern and American Jewish diasporas, was a crucial component in the nourishing of the modern Jewish national sentiment in the first two decades of the 20th century.

At the same time, the opposition to Hatikvah on account of the un-Jewishness of its tune or the ethnic exclusiveness of its text is a proof of how racial discourses had permeated modern perceptions of “being Jewish.” Finally, studying Hatikvah informs us about the modern crisis of the diasporic Jewish community and its splintering into discrete and often irreconcilable groups whose last moment of global solidarity was marked by the attempt to annihilate that very same community during World War II. And, understandably, it offers, by means of a symbol, a lesson about the daily and unsettled contradictions of contemporary Israeli existence.

Text

Naphtali Herz Imber (1856-1909) wrote the poem Hatikvah (Heb. הַתִּקְוָה), with first drafts probably made in Iaşi (Rumania) in 1877 or in Zloczow (Galicia in Poland, today Zolochev in Ukraine) in 1878 (scholars are divided over this issue, and their various views were summarized by Bloom, see note 2 above). Apparently, the poet constantly revised his poem, alone or in the company of Jewish settlers from Rishon Le-tziyyon, adding additional stanzas after he moved to Palestine in 1882. Published for the first time as Tikvatenu (“Our Hope”) in Imber’s inaugural collection of poems Barkai (‘Morning Star,’ Jerusalem, 1886), its superscription reads “Jerusalem 1884”, probably referring to the last revision prior to publication but certainly not to the date of its inception. Here is a translation of the two stanzas of the poem that eventually became, after several alterations (discussed below), the Israeli anthem.

Title page of Naftali Herz Imber's Barkai (Jerusalem 1886)

Its inspiration seems to have been the news about the founding of Petah Tikvah (“Gate of hope”), one of the first modern Jewish settlements in Palestine established with an overt Zionist orientation that reached Imber while still in Rumania in 1878. The themes and phrasings of this poem have polyphonic resonances in Romantic European poetry. Different scholars cited two nineteenth-century patriotic German songs, certainly known to German-speaking Jews, as a possible source of inspiration: Die Wacht am Rhein (text: Max Schneckenburger; music: Karl Wilhelm; Imber’s song, Mishmar ha-yarden is in fact a paraphrase of this German song; see more below) and Der Deutsche Rhein or Rheinlied (by Nikolaus Becker, especially the “As long as” motive). Eliyahu Hacohen, the ultimate connoisseur of the Israeli Hebrew song, who wrote one of the most authoritative studies on Hatikvah ever, notes that a Hebrew translation by Mendel Stern of Die Wacht am Rhein was printed in the journal Bikkurei ha-‘etim ha-hadashim in 1845 and that this translation was widely known.[3]

Another likely source of inspiration of Hatikvah, looking a bit more eastwards, could have been Mazurek Dąbrowskiego, the famous Polish patriotic song written in 1797 by Józef Wybicki that soon acquired the status of a national song. The incipit of the original poem was modified to become Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła, “Poland is not yet lost, while we still live” (compare to “Our hope is not yet lost”) and in this version, it eventually became the national anthem of the Republic of Poland in 1926. The process of gestation and reception of this Polish anthem show similarities to that of Hatikvah.

Alternatively, scholars have invocated the Biblical ‘Vision of the Dried Bones’ (Ezekiel 37, 11-12) as the inspiration for the poet of Hatikvah.

“They say, ‘Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are cut off completely’ Therefore prophesy, and say to them, Thus says the Lord God: I am going to open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people; and I will bring you back to the land of Israel.”

One can see in this diverse set of literary sources of inspiration for Hatikvah how present-day agendas suggest options according to their divergent perceptions of the wellspring of the modern Zionist movement in all its variants. Given Imber’s Galician background, the Polish inspiration of a debased nation struggling to restore its past glory, is of course a probable one. Yet, the German option is not without justification, considering the heavily German cultural and linguistic leaning of the early Zionist intellectuals Central and Eastern Europe. On the other hand, the “Biblical” thesis speaks more about a desire to ground the narrative of Hatikvah on canonic Hebrew texts. Imber, a Jew raised in a traditional family, certainly had access to the Hebrew Biblical text, and indeed maskilic poetry did rely on the Bible. However, the likeness is that a secularized Hebrew poet writing a nationalistic poem in the 1870s would be exposed to the resonances of modern national themes and motives emanating from the poetic milieus of the struggling surrounding non-Jewish nations, Poland, Germany as well as the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires.

The text of Imber’s Tikvatenu was not bound to remain a stable written one once it started to circulate orally. It underwent, in the process of its reception and musical performances, changes and adaptations. The printed version of 1886 is apparently not the original one and resulted from the contacts between the poet and teachers of the Rishon le-Tziyyon school who hosted Imber, such as Israel Belkind, Mordecai Lubman and David Yudlovitch. Some of these changes, included the new title of Imber’s song, Hatikvah, appeared already in the songster ‘Shirei ‘am-tziyyon’.[4] According to Hacohen (see above note 3) and Shahar (see below note 20), further changes in the text were introduced by Dr. Yehuda Leib Matmon-Cohen (1869-1939), who immigrated to Palestine in 1905, served as a school teacher in Rishon le-Tziyyon in that year and later founded the famous Gymnasia Herzliyah in Tel Aviv-Jaffa. The changes from Imber’s ‘Hatikvah ha-noshanah’ to ‘Hatikvah shnot alpayim’ and from Imber’s ‘lashuv le’eretz avoteynu, le-yir bah David hannah’ to ‘Liyot ‘am hofshi be-artzenu, Eretz Tziyyon Yerushalayim’ are attributed to Matmon-Cohen.

Hatikvah in Shirei ‘am-tziyyon - Courtesy of Eliyahu Hacohen

Hacohen also maintains that composer Hanina Karaczewski (1877-1926; sometimes spelled as Chanina Krachevsky; immigrated to Palestine in 1906), who set a choral arrangement of Hatikvah for the Gymnasia Herzliyah was responsible for adding the word “bat” to ‘Hatikvah bat shnot alpayim’ in order to better adjust the text to the rhythmic pattern of the melody. Another source credits educator and Zionist activist David Yellin (1864-1941) with the change from ‘lashuv le’eretz avoteynu, le-yir bah David hannah’ to ‘Liyot ‘am hofshi be-artzenu, Eretz Tziyon Yerushalayim’ and more importantly with the shift in the order of the first and second stanzas that turned ‘od lo avdah tiqvatenu’ into a sort of refrain.[5]

Karachewsky's arrangement of Hatikvah

These textual variants, however, stripped the original poem of its Biblical allusions of messianic hope in favor of references to the territorial Zionist agenda lingering among Hebrew educators in late Ottoman Palestine. These changes circulated therefore mostly in the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine while in the Jewish Diaspora Imber’s original version continued to be more customary at least until 1948. The present-day text then was forged in an elaborate communal process with the participation of various educators from the Yishuv in Palestine over a period of almost two decades. This collaborative ethos is certainly a major feature in the gestation of the Zionist anthem and its popular reception.

Music

In 1884, Imber read his poem Tikvatenu to the farmers of Rishon le-Tziyyon, one of the earliest Zionist settlements in Ottoman Palestine, who received it with enthusiasm. Soon afterward, Samuel Cohen (1879-1940), who immigrated to Palestine from Rumania in 1888 and settled in Rishon le-Tziyyon, set the poem to a melody which he borrowed from the Moldavian-Rumanian song, Carul cu Boi (‘Cart with oxen’). He did so probably between 1887, after the poem appeared in print in Jerusalem and a copy of the book reached him in Moldavia through his brother, and 1888.

Cohen’s own recollection of the events were published in 1937 slightly before his death and many years after they took place. Abraham Yaari later reproduced this crucial testimony and from him this passage is often quoted.[6] It is worthwhile to quote this testimony (with our editorial additions in square brackets) in its entirety (for the first time in English) to understand the context in which Hatikvah emerged into the public sphere as a performed song:

I would like to tell how the song ‘Hatikvah’ and its melody became the anthem of the Zionists.

In the early days [of Zionism] there were no musicians among us in the Land of Israel. Except for [Leon] Igli, one of the six youngsters who were sent to Palestine in order to strengthen the connection between the Russian Hovevei Zion and the employees of the Baron [Rothschild]. And for the earliest songs of Zion we were forced to use imitations of the songs of foreigners. For example, the song ‘Hushu ahim Hushu, narima pe’ameinu’ that R. Yehiel Mikhal Pines wrote was sung to the melody of a well-known Russian song. And in secret I will reveal to you that the earliest pioneers ---and first among them the enthusiast Mikhael Halperin--- used to wander around the streets of Rishon le-Tziyyon loudly singing the Russian revolutionary song ‘Mi za svobodu stradaem / Mi za narod svoi stoim.’ (‘We suffer for freedom, we stand up for our people’). And the beautiful, noble and gentle Halperin, with his blond curls, beats his fist on his heart during the singing --- to express his fervor, bravery and courage…

To the ‘Shirei Yisrael’ of [Lord] Byron [sic, should be ‘Zemirot Israel,’ the name of the Hebrew version of Byron’s Hebrew Melodies] ---translated by Yehudah Leib Gordon [published in 1884]--- Yehudah Grazowsky [aka Yehudah Gur, 1862-1950, immigrated in 1887] applied a melody. Only God knows from which source he adopted it; and we all sang with a weeping voice “Nudu lameyalelet [‘al neharot bavel ‘al shirah ki shavat mi-pi ha-nevel; ‘Oh! Weep for those that wept by Babylon’s stream; Whose shrines are desolate, whose land a dream’]” and he ended with the same sad melody and with tears in his eyes. ‘The wild-dove hath her nest, the fox his cave, Mankind their country -- Israel but the grave!’[7] Also the song ‘Al tal ve-al matar’ by Sara Shapira we used to sing according to a foreign melody.[8] And ‘On the rivers of Babylon’ according to the mourning melody [probably ‘You fell victims in a fatal battle of selfless love for the people’] for the funeral of [Russian revolutionary Andrey Ivanovich] Zhelyabov [1851-1881]. They said that this funeral melody was chosen for ‘By the rivers of Babylon’ by Itzhak Epstein. To the truth of this claim, I cannot be held responsible.

In that same year Baron Rothschild toured the Land for the first time [1887], and my older brother, Zvi, tried to plant wheat on the soil of the moshava [agricultural settlement] Yesud Ha-ma’alah. In those days, the poet Naftali Herz Imber was in Rosh Pina. He gave my brother the collection of his songs Barka’i, with a warm dedication as a souvenir. And my brother sent this book to me in the diaspora. From all the songs the one I liked was ‘Shir Hatikvah’. In particular I was impressed by the last verses: ‘for the Jewish people our hope is finally come’. A short time later, I emigrated to Palestine.

In my home country [Maramureş county, today in northwest Rumania], we used to sing in the choir the Rumanian song ‘Hâis, cea!’ (‘Right! Left!’; with this cry one induces the bulls while ploughing) [This is the refrain of the song Carul cu Boi]. When I arrived at Rishon le-Tziyyon fifty years ago [1888] I saw that ‘Hatikvah’ was not sung, nor were the rest of the songs in [Imber’s collection] Barka’i. I was the first one to start singing ‘Hatikvah’ with this foreign melody that I knew, the same one that is sung today in all the Jewish communities. At the beginning, neither the song nor the melody [of Hatikvah] received attention. We used to sing other more important songs according to the melodies by… [Leon] Igly, who was a student at the Conservatory of Saint Petersburg [and later on an opera singer in that city]. He composed melodies for two songs about Rishon Le-Tziyyon. One by Imber and the second one ‘Ah, Rishon Le-Tziyyon’, and another melody for the song by Imber ‘Mishmar ha-yarden’.[9]

The precise source of the melody of Hatikvah, i.e. the attribution of the melodic adaptation to Samuel Cohen following his testimony, was then public at least from 1938. However, it remained curiously concealed from public attention until it surfaced independently in two separate publications appearing barely a year apart. The first publication is the aforementioned one by Eliyahu Hacohen (note 3 above). The other one is a self-published monograph by the music critic Menashe Ravina (1899-1969).[10] Since then, a barrage of additional information or reworking of the story were published, mostly without adding spectacular novelties (e.g. later publications by Hacohen himself and by Nathan Shahar, below note 20). As mentioned at the opening of this essay, Internet websites have recycled this information in countless variations without further examination.[11]

Although Carul cu Boi is usually described as “folk song,” at least its text is relatively “modern” for it bemoans the progress introduced by electricity, the vapor and the railways while nostalgically celebrating the old ways of plowing the fields. Put differently, when Samuel Cohen learned the song in Rumania, it must have been a relatively new creation. The melody of Carul cu Boi is therefore not original to this song but a variant of a melodic pattern circulating in Rumania/Moldavia.[12] According to Levin (note 1 above) the song about a farmer carting his oxen to the market “was known by then [1888?] as Carul cu Boi (Wagon and Oxen)” and “the lyrics [of Carul cu Boi] had been applied at some point [to the melody] prior to 1888 by G. Popovitz” (should probably be Popovici). However, this piece of information that has been quoted widely on the web since its publication online is not supported by any concrete reference. Most probably there is a confusion here with the name of the Rumanian musicologist and composer Timotei Popovici (1870-1950) who published the same melody set to the song ‘Cântecul de Mai’ (incipit: ‘Luncile s-au deştepta’) that continues to be quite popular in Rumanian and Moldavian schools to this day.[13] In short, it appears that the melody that Samuel Cohen adapted to Hatikvah, a melody that is not distinctively Rumanian, circulated in Moldavia among Jews and non-Jews and was adapted to several texts in Rumanian, one of which was Carol cu Boi. Therefore, the ascription of the authorship of the melody of Hatikvah to Samuel Cohen, as it appears in countless sources in the web, does not reflect the widespread folk practice of contrafactum that lies behind the turning of Hatikvah into a song set to music.[14]

Moreover, the immediate reception and musical arrangement of Hatikvah was not as swift as it appears in many sources. Crucial (and overseen) information regarding the early competitors of Hatikvah for the “title” of the national Jewish song appear further on in the second part of Cohen’s testimony that we translate in its entirety:

We could not imagine turning ‘Hatikvah’ into our national anthem. The song ‘Mishmar ha-Yarden’ was sung then as a national anthem; according to our Zionist feelings, this [latter] song deserved that honor.

It is worthwhile noticing that the young intelligentsia of Rishon Le-Tziyyon (and all the young intelligentsia of Yehudah [central Israel in the terminology of the early Yishuv]) established the custom for the first time to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. The first pilgrimage was under the guidance of [the teacher] David Yudelevich [1863-1943] because he was familiar with the roads of Jerusalem and knew its intellectuals [maskileyah]. [Eliezer] Ben Yehudah, David Yellin, and Efraim Cohen arranged a performance in honor of these ‘pilgrims.’ It consisted of the first play in Hebrew, ‘Zeruvabel’ by [Moshe Leib] Lilienblum, written in Yiddish and translated into Hebrew. Within the play songs were inserted, and among them ‘Mishmar ha-Yarden’. And the song was not performed according to the melody by [Leon] Igly but to the melody of the German song ‘Die Wacht im Rhein’. And indeed, our youth wished to make ‘Mishmar ha-Yarden’ our national anthem. And when the leader [Vladimir] Zeev Tiomkin [1861-1927] came to visit us we received him with the song ‘Mishmar ha-Yarden’.

Our wish was not fulfilled. Not only ‘Mishmar ha-Yarden’ but also all the rest of the melodies by Igly to the songs of Zion were rejected by the public and were forgotten. It is a pity that those early sounds of the passion of our souls were silenced. Our children who come after us will not feel those inner feelings and those sounds that tie them to their parents and to the pioneers of the passing generation.

Among the songs of Zion that were sung at the time in Rishon le-Tziyyon was also ‘Hatikvah’--- especially in the hall of Rabbi Zvi Levontin. The hall of Rabbi Zvi Levontin was called the Rishon le-Tziyyon Hostel. There the youngsters of the settlement ate [at the Hostel] and there our guests and passers-by visited it. Rishon was considered then the center of the Yishuv. Those who came to Palestine tried first of all to visit Rishon. The tendency here was to sing ‘Hatikvah’ often due to its catchy and pleasant melody; but it was still not considered a national anthem.

Then came a big immigration to Palestine. In the days of [Hovevei Tziyyon leader Vladimir Zeev] Tiomkin the settlements Rehovot and Gedera were founded. We thought that at the foundation of each settlement there was a melody that fitted it – according to the character of its population and perhaps also according to its geographical characteristics: Rishon le-Tziyyon and its song ‘Ah, Rishon le-Tziyyon,’ Gedera and the song of the Biluim, ‘Hushu ahim hushu’ --- Hedera and the song ‘Mas’at nafshi’ by Mane. I still remember how the young Moshe Smilansky deafened my ears by singing the song ‘Mas’at nafshi’ out of tune, especially when he was excited by the verse ‘Ma na’amat tor ha-aviv’… This happened on the year of the founding of the moshava Hedera. The song of Rehovot was ‘Hatikvah’... Four hundred Hebrew laborers worked there then; and when they returned from their working places they sang ‘Hatikvah’.

In spite of our insistence, the public did not respond positively to the original melody of ‘Mishmar ha-Yarden’. They liked the melody of ‘Hatikvah’ better. And the song became famous among the whole people and developed anyway into the Zionist anthem. In my opinion there is no need to investigate the composer who composed the melody of this song. After all, it is not a genial work; and it is even not important. Only this is important: our masses chose ‘Hatikvah’ and its melody. And may I add that time after time I participate in gatherings, conferences, and parties, and the song ‘Hatikvah’ is sung in a ‘formal manner,’ I am reminded of the first time that we sang this song and I consider myself the luckiest person because I had the privilege of being the first one to sing the song ‘Hatikvah’.[15]

Despite this clear account of the genesis of Hatikvah’s melody in websites and articles about our song, the melody is credited not to Samuel Cohen’s adaptation but as a composition by Leon Igly. Consistently we find it stated that Samuel Cohen, was then the first one to set Hatikvah to music at the request of Israel Belkind from Rishon le-Tziyyon. Thus for instance on the website of the Milken Archive of American Jewish Music we read that:

“Leon Igly, a musician and settler in Zikhron Ya’akov who had studied at the conservatory in St. Petersburg, has been identified as the first composer to set Tikvatenu to music—devising a musical version in 1882 that apparently ignored the strophic structure of the poem and provided instead a through-composed version without musical repetition from one stanza to the next. In that form it proved difficult to sing communally, and it did not take off—despite token prizes offered to children who could learn it.”[16]

For the sake of accuracy, it is worthwhile to provide, as we did with the memoires of Samuel Cohen, the entire original text as Israel Belkind (1861-1929) included it in his memoirs. These memoirs, which provide another angle to the same historical context described by Samuel Cohen, appeared many years after the author’s death but on the other hand are closer than Cohen’s in time and place to the events leading to Hatikvah.[17]

In that year [1884] our poet Naftali Herz Imber was in Rishon le-Tziyyon. He spent two years in our country, but most of the time he lived at the home of the Lord Oliphant on Mount Carmel, and eventually came to Jaffa and lived in that city and in Rishon le-Tziyyon. And in this settlement he split his time between the home of Joseph Feinberg and our home, namely in the house of my brother. And thus, we had the privilege that in our house he wrote some of his best poems that eventually published in his collection of poems titled ‘Barka’i.’

The song ‘Hatikvah’ was the most privileged among his poems, and has become our national song. However, the song did not receive this honor in our country but rather abroad, and from there it returned to us, to the Land of Israel. In Rishon le-Tziyyon they used to sing then with great enthusiasm the songs ‘Mishmar ha-yarden’, ‘Hashofar’, and especially the song of the pioneers which was dedicated to Rishon le-Tziyyon and its institutions. The sons of Rishon le-Tziyyon perceived in this song their own history, and sang it with great pride [here the song is quoted]

As one can see, this song suffers from problems of grammar, as also does ‘Hatikvah’ and the rest of the songs by Imber. But who cared about grammar? With a beautiful melody they used to sing the songs with great enthusiasm, the adults sang, the children sang.

And if there are poems, then they need melodies. As usual they used to solve this question as follows: you take a Russian, Ukrainian, Rumanian or also Arabic or Turkish melody, adapt it to the new Hebrew song, and everything is ready for singing. And so our national song ‘Hatikvah’ is also sung with a foreign melody. Some say it is a Russian melody. Other claim that it is Rumanian, and there are those who say that it is Turkish… But at that time [early 1880s] lived in Rishon Le-Tziyyon a composer of ours, who crafted melodies for most of Imber’s songs, and this composer was Mr. Igly, and it is interesting how he came to Rishon Le-Tziyyon. [Here follows the detailed story of the six Russian youngsters that came to strengthen Baron Rothschild’s settlements]. The sixth one was Igly. He lived previously in Saint Petersburg and it seems to me that he used to sing at the choir of the opera there. And in that city lived my sister [Olga] who played a prominent role in the Hovevei Tziyyon [movement] there [in Saint Petersburg]. Of course when he came to our country, my sister gave him letters and greetings for me, my brother and my [other] sister [living in Palestine]. The labor in Rishon Le-Tziyyon was very hard for him, and he used to ask me to release him from his situation. I used my influence on [Yehoshua] Ossovetzki [1858-1929], the administrator [of the Baron], and [Igly] was not required to work intensive labor. The administrator loved music, and Igly was one of the regulars at his home.[18] That was at the same time that the poet Imber was in Rishon Le-Tziyyon and wrote there his poems and in fact, Igly took upon himself to set up melodies to those poems.

The whole moshavah then started to deal with poetry and singing. Imber used to write a new poem, Igly would set up a melody and perform it for the first time at our home. They say about me, and justly so, that I do not know how to sing, but I used to get the melody I heard and transmit it to others… Therefore, I used to leave the house, gather all the children of the moshavah and give them a singing lesson. I used to promise candies and chocolate to the children who learned the [new] song and its melody by heart. Frequently, I used to pull into this work one of the farmers, Mr. Reuven Yudelevitch [1862-1933], who used to play the violin in order to promote the new songs. The children of this Yudelevitch [he had eight] where the best “buyers” of chocolate.[19]

And because I already revealed the secret, that I am no expert on musical matters, I can say that I cannot estimate to what extent Igly’s melodies were fit [to the poems], to what extent, they were Hebrew [in their melodic character]. I can only point out a disadvantage in his works, a practical disadvantage that may have been a great artistic merit. He did not compose one melody for each poem, but rather a unique melody for almost each stanza of the poem. And for this reason it was difficult to learn them… Also for the song ‘Hatikvah’ he composed different melodies for each stanza, and for this reason the public accepted the simple and monotonous tune that came from abroad and Igly’s melodies were totally forgotten.

Although Igly’s settings did not survive, one can just imagine what kind of music such a person would design for Imber’s poems. As an immigrant from Saint Petersburg, student at that city’s most prestigious Conservatory and member of the opera’s choir, Igly must have experienced in the Russian capital first-hand music of the highest artistic quality. Composing a different melody (or perhaps variants of one melody, since one cannot know what “difference” means in this context) for each stanza of a strophic song was a standard practice of Russian romans and opera composers. In short, one can surmise that there were certain disparities in the musical taste and sensibilities among the Jewish immigrants who gathered in Rishon Le-Tziyyon, from the ones from the sophisticated imperial capital of Russia to those who arrived from the Eastern confines of Europe, such as Moldavia (i.e. from the former Ottoman Empire). It is in this social context of difference that we need to read the Igly affair in connection with Hatikvah.

Reception and Theories of Origins

Hacohen found that the text of Hatikvah reappeared in the earliest documented songster printed in the Jewish settlement in Ottoman Palestine, the aforementioned ‘Shirei ‘am-tziyyon’ and also it is the opening song of another important and more widely distributed Hebrew songster ‘Kinnor tziyyon’ also published by Abraham Moshe Lunz (Jerusalem, 1903), with the title Hatikvah instead of Tikvatenu. These publications and the prominent positioning of our song in them reflected the central status that it had already acquired in the proto-Zionist song repertoire of Ottoman Palestine.

Title page of Kinnor Tziyyon (Jerusalem 1903)

Abraham Moshe Lunz, editor of Kinnor Tziyyon

Yet, in spite of its rootedness in the Hebrew Yishuv, Hatikvah attained its status as a national sonic icon on European lands. Indeed, the earliest known printed version of Hatikvah with its melody in music notation appeared far away from Palestine, almost at the same time when the text was being printed as a “folksong” in Meirovitz’s ‘Shirei ‘am-tziyyon’ (to be sung to “the well-known tune” as written in the title there).

The first musical notation of Hatikvah is included in a collection of lieder for voice and piano titled Vier Lieder mit Benutzung syrischer Melodien… (Leipzig, 1895), arranged by Cantor S.T. Friedland from Breslau. The song found its way to Breslau via an envoy from the Land of Israel, Moshe David Shuv. A firsthand testimony from a witness close to the individuals involved in this encounter provides us with another decisive moment in the saga of Hatikvah and demonstrates how crucial the agency of individuals is in the making of culture.[20] A Rumanian-born envoy from Rosh Pinah (one of the earliest Zionist settlements in Palestine), Shuv was in Europe on a fund-raising mission on behalf of the Sha’are Tzedeq hospital in Jerusalem. In the year 1894, while visiting Breslau, Shuv sang songs from the Land of Israel to the students of the famous rabbinical seminary of that city. One of these students, Rabbi Efraim Finkel, introduced Shuv to Cantor Friedland who wrote down the words and music of Hatikvah. Hatikvah was thereafter included in Friedland’s collection of lieder, next to other of the songs from the Land of Israel that Shuv transmitted, under the romantically-loaded German title ‘Sehnsucht’ (‘Longing’).

Another telling testimony corroborating the astoundingly rapid reception of Hatikvah in Europe is the prophesy by the Galician Zionist writer and journalist Isaac Fernhof (1866-1919). In his utopic text ‘Shene dimiyonot’ (‘Two visions’, included in the second issue of his short-lived journal Sifre sha’ashu’im, Krakau: J. Fischer, 1896), Fernhof predicts, under the impression of Herzl’s Der Judenstaat published just a few months earlier in February 1896, the establishment of ‘Medinat Israel’ (‘State of Israel’) whose anthem (in his words ‘manginah le’umit’, ‘national melody’) will be Hatikvah.

The entry on Naftali Herz Imber in the Jewish Encylopedia (London, 1901-1906) is a further testimony of how fast the song had caught in Europe, especially through its performances in the Zionist Congresses on 1900 and 1903: “Imber has, however, obtained his reputation by the mastery of Hebrew verse displayed in his two books of collected poems, ‘Barḳai’ (1877-99). These show great command of the language. His most famous poem is, ‘Ha-Tiḳwah,’ in which the Zionistic hope is expressed with great force, and which has been practically adopted as the national anthem of the Zionists.” For the first time the expression “national anthem” is used here in relation to Hatikvah. This occurred at a time when back in Palestine its status as “national anthem” was still contested by other songs as the witnesses of Samuel Cohen and Israel Belkind show while abroad the Zionist leadership continued to try and find a new song as the movement’s anthem by calling for submissions to a contest.

At a time when new songs and adaptations of existing songs to new Hebrew texts in the incipient Jewish settlement in Ottoman Palestine became “folksongs” almost overnight, as we have seen in the testimony of Samuel Cohen, the adaptation of the Moldavian/Rumanian melody to Hatikvah had become anonymous in an astonishingly swift process. Even the distinguished musicologist Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, who settled in Jerusalem in 1907 and was close in time and space to the place of creation of the song, approached it, from the musical point of view, as an anonymous folksong. He also published Hatikvah as early as 1912 in his pioneer songster for Hebrew teachers in Palestine.[21] Many years later, Idelsohn would testify that when he first arrived to Palestine, the Jewish children knew only two Hebrew songs, Hatikvah and “a song by Bialik” (most likely ‘Tehezakna’ that competed with Hatikvah for the title of anthem of the Zionist movement).[22]

Added to the rapid circulation of Hatikvah were its early translations to other languages, especially those by Israel Zangwill to English and Heinrich Loewe to German. From the moment Hatikvah started to circulate as a “folksong,” spectacular theories about its musical origins started to thrive. Eliyahu Hacohen set the record straight in two trailblazing radio programs on Hatikvah (1965) aired by the Israeli Radio followed by Menashe Ravina’s monograph (1968) by making public Samuel Cohen’s testimony that was available since 1937 but buried in the pages of an obscure Hebrew agricultural journal. These hypotheses reveal, as we have seen in the case of the text of the song, more about their proponents than about historical realities.

Comparative Musicology Hypotheses

In the fourth volume (1923) of his Hebräisch-orientalischer Melodienschatz (HOM, Berlin, Jerusalem, Leipzig, Vienna, 10 vols., 1914-1932) dedicated to the music of the “Oriental Sephardic” Jews, the distinguished musicologist Abraham Zvi Idelsohn carried the first thorough analysis of the cross-cultural melody-type to which Hatikvah belongs. In the spirit of Vergleichende Musikwissenchaft (comparative musicology), Idelsohn compared a set of melodies a propos a discussion about a certain “south-Slavic melos” that is cross-culturally widespread and of which the Western Sephardic piyyut Lekh le-shalom geshem (see detailed discussion below) is one specimen. Idelsohn then offers a table that includes Spanish, Polish and Czech (one of Smetana’s Moldau themes; see below) versions of this “melos”. This comparative table includes the melody of Hatikvah as one specimen of this “melos” (Idelsohn 1923, p. 115-117, table in p. 116). It was indeed an awkward move by Idelsohn to interpolate this table in a volume not precisely dedicated to the “Slavic melos.” One can surmise that he was perhaps eager to make public his findings about the melody of the emerging national Jewish song and its Sephardic relative.

Idelsohn reproduced this table with few amendments in his seminal book Jewish Music in its Historical Development (New York, 1929, pp. 222-223) and later on it was reprinted by the musicologist Peter Gradenwitz and by Menashe Ravina in his above-mentioned monograph on Hatikvah.[23] This table remained a source for references about this set of melodies ever since. For example, Paul Nettl, in his often-quoted study National Anthems, tried to tailor to Hatikvah, inspired by Idelsohn’s table, a medieval Hispano-Arabic ancient pedigree by linking it to the Spanish folksong ‘Virgen de la Cueva’ that was published by the folklorist Felipe Pedrell and was already included in Idelsohn’s table of 1923.[24]

Idelsohn returned to the melody of Hatikvah in volume 9 of HOM (1932, p. xix) that is dedicated to the folksong of the Eastern European Jews (not exclusively as it turns out for it includes copious “Palestinian” materials, i.e. Hebrew songs from the Jewish Yishuv in Mandatory Palestine). He includes Hatikvah among the “modern Hebrew songs” (no. 147 in the original version by Imber, not the “Palestinian” one and with a transliteration in Yiddish pronunciation) as well as a Yiddish parody (no. 200 only the first part of the melody, text by “S. Lejman”). He expands the geography of his comparative study to include Rumanian (‘Cucuruz’ rather than ‘Carul cu boi’ of which Idelsohn apparently was unaware), Ukrainian and even Armenian (a song about the hope of the Armenian victims of Ottoman persecutions!) songs belonging to the same melody-type (mostly of the first part only).

The tunes of the Moldavian/Rumanian songs that we already mentioned such as ‘Carul cu boi,’ ‘Cucuruz cu frunza-n sus,’ and ‘Cântecul de Mai’ that lay in fact behind the melody of Hatikvah are all variants of a well-known melody-type found throughout Europe in both major and minor scale versions. This melody-type has been the object of a study in the spirit of comparative musicology that was not mentioned in any of the Israeli studies of Hatikvah. The distinguished ethnomusicologist George List dedicated part of his important essay “The Distribution of a Melodic Formula: Diffusion or Polygenesis?” to this pervasive melody-type that been circulating throughout Europe for centuries and has generated innumerable incarnations of which the Rumanian-Moldavian melody of Hatikvah (also mentioned by List) is just one of them.[25] This pervasive and ubiquitous European melody-type was the engine that activated during the first half of the twentieth century the need for speculations in order to find a more genuinely “Jewish” or “ancient” origin for the tune. We shall examine below the pedigree of these “Jewish” hypotheses.

But before we move into these hypothesis one should point out that the comparative musicological approach was never abandoned and in fact reached another peak with the remarks by Philip Bohlman in an essay claiming, strangely enough for a discussion of Hatikvah, that Zionist song existed “before Hebrew song.” Bohlman introduces into the discussion other melodic “relatives” of Hatikvah such as the Swedish folksong, ‘Ack Värmeland, du Skön’ and the anonymous French pastoral song (in major) ‘Ah, vous dirais-je maman.’ This is the name that this French song acquired when it was first published as an instrumental piece in 1761 (in François Bouin, La Vielleuse Habile Ou Nouvelle Méthode Courte, Très Facile Et Très Sûre Pour Apprendre À Jouer De La Vielle...). The name derives from the children rhyme added to it apparently some years earlier. This melody is known today on a global level as ‘Twinkle, twinkle, little star.’ Mozart’s variations (K. 300a) immortalized it and since then it was endlessly reproduced.

Bohlman is the only scholar I know who refers to George List’s article in the context of Hatikvah and stresses, on the basis of its structural affinity with an endless number of European tunes, the lack of individuality of the melody:

“What do such peregrinations of ‘Hatikvah’ throughout European song history reveal? First, they make it clear that there is nothing special or even distinctive about ‘Hatikvah’ as a song. Second, the histories of melodic distribution and the skeletons produced by computer analysis notwithstanding, ‘Hatikvah’’s impact on the earlier Zionist movement was indeed very special and distinctive. Third, it is because the melody is so quintessentially quotidian and unexceptional that it could become such a powerful emblem of nationalism.”[26]

Bohlman suggests then that precisely the unremarkable musical quality of the melody of Hatikvah (remember Samuel Cohen’s caustic remark about it, “it is not a genial work”) fitted the assortment of pasts that strove for representation within Zionist aesthetics. And yet, from the story unfolding in this essay one cannot but observe that as much as Hatikvah may be “the most iconic of all Zionist songs,” (per Bohlman) its immediate reception had more to do with the in-house set of codes embedded in its Hebrew text rather than with the universal music archetype that set those words in motion. This is one of the main reasons why locating an identifiable melodic Jewish pedigree for this melody became a matter of public concern.

Sephardic Hypothesis

The melody deriving from a Jewish context that is frequently mentioned as the possible forerunner of the melody of Hatikvah (including by Idelsohn), is found in the liturgical repertory of the Western Sephardic communities. It is the melody of the piyyut Lekh le-shalom geshem (‘Go in peace, Rain, and come in peace, Dew’) included in “The Prayer for the Dew” ceremony on the seventh day of Passover. From this context, the Western Sephardic Jews also adopted it to the Hallel Psalms for the same festival. The piyyut with its melody appears in the early collection The Ancient Melodies of the Liturgy of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews by Emanuel Aguilar and David Aharon de Sola (London, 1857).

This assumed Sephardic link of Hatikvah was pursued in an early stage by Rabbi David de Sola Pool of the Shearith Israel congregation of New York City. In 1917 De Sola stated:

“Another famous Sephardic melody is one of those to which the Hallel is sung… When in the New York Tribune of September 26, 1915, I traced back its age as demonstrably earlier that 1750, [American music critic] Mr. H.E. Krehbiel [1854-1923] rebuked me for my needless caution… But although not much is known of its ancestry, I can give authentic information about its descendant, for its child is no less famous a melody than the one to which Hatikva is sung. To my certain knowledge, the Rev. Mr. [Asher] Perlzweig [Kremenetz-Podolsk, Ukraine, c.1870 - Oxford 1942], hazzan of the Finsbury Park Synagogue, in London, adapted the traditional Sephardic melody to Hatikva. The relation of the two melodies is so close as to be obvious to even the least musical of us.”[27]

Since the De Sola left London for New York in 1909, we can assume that the story was handled to him (“to my certain knowledge”) on this date or earlier. This extraordinary account linking the famous cantor from London to the Zionist anthem has been perpetuated in the scholarly literature as well as in narratives that are more popular. It reappeared as recently as 2007 in an Israeli documentary film directed by Reuven Hecker and titled precisely Lekh leshalom geshem. The film cleverly focuses on the Sephardic tune as the most “ancient” specimen of the melody-type, dramatically leading towards the end to its most celebrated reincarnation, Hatikvah.

However, it should also be noted that De Sola Pool’s testimony was contested months after its first publication. Dr. Joseph Reider (1886-1960), Bible scholar and polymath, criticized De Sola Pool with the following remarks:

“It is interesting to note that also the melody of Hatikvah, the cheval de bataille of the Zionists, which of late is being used for Shir ha-ma’alot [on this matter, see below] and other liturgical purposes, appears to be foreign and secular, as it main theme occurs in Smetana’s symphonic poem entitled On the Moldau. I am aware of Dr. Pool’s contention that this tune is rather an adaptation from the old Sephardic tune to Hallel. However, aside from the authentic information and certain knowledge of the fact which Dr. Pool claims to have and which I dare not to impugn, the assertion is based on the similarity of the first or ascending figure or phrase in both melodies. But this is not sufficient as a criterion for authenticity, for the same inceptive figure or musical germ [sic!] may be found also in other compositions of various lands and ages. In fact, the progression la, ti, do, re, mi, is characteristic of the minor mode and is quite common in folksongs of all climates. I found it even in English folksongs of the Elizabethan period. One thing is certain, that Smetana did not derive his melody from the Sephardic Hallel. As is well known, this Bohemian composer utilized popular tunes of Bohemia as themes to his larger compositions. The most striking thing is that there is more similarity between Hatikvah and Smetana’s melody than between the former and the Sephardic Hallel, especially with references to the second or descending figure. However that may be, in its present elaborate shape it appears more like a folksong than an ecclesiastical [read: synagogue] chant, and hence it is inappropriate for liturgical use.”[28]

Reider’s remarkable intuitive, if polite, response is one of the earliest (and pre-Idelsohnian) comparative musicological critiques of the theories of “origin” of the tune of Hatikvah. By stressing the wide spread usage of the melodic patterns, Reider disarms the Sephardic hypothesis even if De Sola Pool’s testimony is not per se contested. In short, despite this prestigious “Jewish pedigree” (and the Portuguese Jews who sing Lekh le-shalom geshem held an even stronger grip on Judaism having to overcome the forced conversions of the late medieval period), it is extremely improbable, as Reider already stated, that this melody could have ever been the source for the tune of Hatikvah.

On the other hand, a possible relation between Lekh le-shalom geshem/Hallel (and another Jewish melody, the Leoni Yigdal, see below under Ashkenazi hypothesis) with the Italian predecessors (see below Italian Renaissance hypothesis) could be explored. Many Portuguese Jewish liturgical melodies originated in the Spanish-Portuguese communities of Venice and Livorno and migrated from there with itinerant cantors to other communities such as Amsterdam and London. The Sephardic Hallel is well known as a prayer that absorbed new melodies, some of them borrowed from the surrounding non-Jewish society.[29]

Ashkenazi Hypothesis

Also Ashkenazi melodies competed in the race for the origins of the tune of Hatikvah. The famous tune for the piyyut Yigdal elohim hay, known as the Leoni Yigdal after its alleged composer, Meyer Lyon, has been another source for the “Jewish” hypothesis of the origins of Hatikvah. Meyer Lyon, a legendary Jewish cantor/opera singer, was in the 1760s-1780s a meshorer (assistant cantor) at the Great Synagogue at Duke’s Place in London and later on served the Jewish congregation of Kingston, Jamaica until his death in 1796.

Several authors have already argued that melodic similarities between Hatikvah with Jewish melodies do not hold for more than the first two or four opening bars of the tune and thus any direct connection, such as the one between the Leoni Yigdal and Hatikvah, should be discarded. Yet, in spite of all the accumulated knowledge on the subject, a full rerun of the whole argument about the relation between Leoni Yigdal and Hatikvah appeared in July and August of 2007 at the Internet forum Jewish Liturgical Music.

Peter Gradenwitz drew in even more confusion into the archeology of Hatikvah’s melody when he related a direct testimony by the composer Rabbi Israel Goldfarb (1879-1956) in a letter to him from 1948. According to Goldfarb, who met in his youth the poet Imber in New York, the origin of the melody was in an unpublished setting of the prayer ‘Vehavi’enu le-Tziyyon yirkha’ (from the Mussaf prayers for the first day of Rosh Hashanah according to the Ashkenazi rite) by the famous cantor Nissi Belzer (born Nisson Spivak, 1824-1906). It is probable that, if this piece of information is reliable, the opposite may be truth. Belzer probably became aware of Hatikvah when it already circulated widely in Eastern Europe by the mid-1890s (as we have seen above) and found pertinent to quote its melody in a prayer expressing specifically the longing of the Jewish people for Zion.[30]

The “Jewish” hypotheses of the origins of the Hatikvah melody strove to provide an authentic pedigree to the tune of the song that quickly attained the status of “the” national Jewish song. Other hypotheses attempted to provide the tune with another, characteristically modern stamp of authenticity, namely “antiquity.” This idea is developed in the next paragraph.

Italian Renaissance Hypothesis

Another closer variant of the melody of Hatikvah comes from even more remote and unsuspected sources. In 2004, the Israeli musicologist Don Harrán dedicated a substantial section of his article on the barabano to a widespread folk melody from north-east Italy documented since at least 1608 that shows remarkable structural affinities with melody of Hatikvah.[31] Known as La Mantovana, this melody was set to several texts of which ‘Fuggi, fuggi, fuggi da questo cielo’; attributed to the Italian tenor Giuseppe Cenci, aka Giuseppino del Biado (died in 1616), is the most widespread one in websites, publications and films carrying the history of the tune of Hatikvah. This version of the melody-type spread throughout the Italian Peninsula and beyond (with the spread of Italian musicians of the late Renaissance, several of whom were of Jewish origin, to European courts) with different names such as partita, padovana, villanelle and “Ballo di Mantova”.[32] Its longevity in Bolognese folk music is apparent and its high degree of melodic similarity with the melody of Hatikvah is remarkable indeed. Harrán discussed this striking melodic coincidence crafting it on careful theoretical terms such as the concepts of unconscious paradigms/archetypes versus “natural” evolutionary mutations/species. He does not propose however any specific chain of transmission to explain how or why barbarano and Hatikvah could be linked.

Two years later, Nathan Shahar recapitulated this information in his chapter on Hatikvah without acknowledging the earlier article by Harrán. He provides just one of the countless Italian reincarnations of this tune, the one by Gasparo Zanetti, “from a manuscript [sic] that arrived to my hands”.[33] Unlike Harrán, Shahar had no misgivings in claiming that this Italian song is the “oldest source” of the melody of Hatikvah (even though he mentions the attribution to Samuel Cohen).

The Great Composer Hypothesis

We have seen that the melody-type of Hatikvah has endless variants, and that notable composers used some of these variants. This similarity linked Hatikvah to the great chain of genial Western composers and the case of Mozart is pertinent here. Comparisons between Hatikvah and ‘Ah, vous dirais-je maman’ (included in Baltsan’s publication, see above) underscore the attempt to “elevate” the pedigree of the national anthem by suggesting a possible (even if not direct) link to Mozart.

However, the most famous “relative” of the first melodic phrase of Hatikvah in the canonic repertoire of Western classical music is, as widely disseminated, the first main theme of Vltava (The Moldau), no. 2 in the symphonic poem Má vlast (“My Fatherland”) by the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana which have been already mentioned in this essay. Although no direct relation between these two melodies can be sustained, they obviously drink from the same well as George List has shown and as Reider has suggested.[34] List’s arguments showed that it is impossible to trace clear-cut genealogies of such a widely diffused melodic pattern.

And yet, the idea that Hatikvah stems from Smetana’s Moldau was too attractive to many to be rejected pointblank. Perhaps the practice that strengthened this idea was that Smetana’s piece was played as a subterfuge substitute for Hatikvah by the Hebrew section of the Palestine Broadcasting Service during the British Mandate of Palestine. The issue of playing Hatikvah during PBS broadcasts was amply studied now by Andrea l. Stanton based on first-hand documentation, a file on this issue kept at the Israel State Archive.[35]

When the Mandate’s radio station opened its transmissions, it broadcasted on December 30, 1936 a live concert of the Eretz Israel/Palestine Philharmonic Orchestra (later on Israel Philharmonic Orchestra) under Arturo Toscanini from the Edison Theatre in Jerusalem. The concert ended with the British anthem and Hatikvah. The technicians were supposed to cut the broadcast short before the playing of Hatikvah, following the policy of the Mandate Government that no “national anthem” except the British was to be transmitted, but for some reason they did not. This was the first and last live broadcast performance of Hatikvah on the PBS. From then on, it was banned from the PBS until the end of the British Mandate, although as Stanton stresses the overall Mandate Government’s policy as to when Hatikvah could be played in public events was not always clear. Efforts by the newly-appointed PBS director Edwin Samuel from 1945 on, under the pressure of the Music Department’s director Karl Salomon, to put an end to this ban were unsuccessful.

Eliyahu Hacohen still had to disclaim this link between Hatikvah and Smetana’s symphonic poem as late as the early 1970s in the legendary Israeli TV program ‘Sharti lakh artzi,’ (‘I sang to you, my land’), an invaluable documented history of the early Hebrew song. The second program of the series’ first season (1974) was dedicated to the songs of Rishon le-Tziyyon and the first ‘Aliyah. In this program, Hacohen and his partner in the production, the play writer, poet, scholar, and journalist Dr. Dan Almagor, organized a performance of the Rumanian/Moldavia ‘Carol cu boi’ by a Rumanian Jewish immigrant to show where the musical origins of Hatikvah laid. Hacohen remarked to those “who still think that the national anthem is based on Smetana,” that this (Rumanian song) is the “true” original melody.

A Secular Anthem, Religious Song, Concert Lied or Popular Hit?

The reception of Hatikvah was multifaceted and multi-dimensional. That the narrative of the secular national anthem prevailed obscures the other uses of the song that spread parallel to its increased canonization as the hymn of the territorial Zionists.

Competing for Zionist Recognition

The road of Hatikvah to recognition as the anthem of the Zionist movement was not a straight one. In spite of its broad early acceptance as one of the main songs of Zion, Zionist institutions and leaders did not rush to adopt it as their anthem. In fact they resisted it. Well-known was the dislike of Theodor Herzl towards the song (in fact towards its poet-author who was an embarrassment to some Zionist leaders), and in fact he openly supported the German song ‘Dort wo die Ceder’ (promptly translated into Yiddish and Hebrew) as the anthem of the movement he founded, as we have extensively discussed.[36] In spite of Herzl’s dislike for Imber, the poet, who never attended a Zionist Congress, continued to play his cards based on his increasingly successful song. He wrote to Herzl during the 1901 Basel Congress that: ‘I am a delegate at large and my credential is Hatikvah . . . and, although the Zionists treated me ill, I am still a Zionist and am happy to see my dreams realized.’[37]

Two competitions for a Zionist anthem, the first one proclaimed in the newspaper Die Welt in 1898 and the second by the Fourth Zionist Congress in 1900 came to nothing because of the unsatisfactory quality of the songs submitted.[38] At the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel in 1901, one of the sessions concluded with the singing of what was still called Tikvatenu. During the Sixth Zionist Congress (Basel, 1903), it was sung by those in favor of the Palestinian (expressed in “An eye still gazes toward Zion”), rather than the Ugandan territorial option.

The Seventh Zionist Congress (Basel, 1905) ended with an “enormously moving singing of Hatikvah by all present,” a key moment in the affirmation of its status as a patriotic song with a national anthem profile. Although already proposed by David Wolffsohn, the formal declaration of Hatikvah as the Zionist anthem was only made at the Eighteenth Zionist Congress in Prague in 1933 through a motion by Y.L Motzkin that addressed both the flag and the anthem of the movement.

Under the British Mandate of Palestine, Hatikvah was the unofficial anthem of the Jewish settlement in Palestine. It was sung at the opening of the ceremony of the Declaration of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948, and then played by members of the Palestine Philharmonic Orchestra at its conclusion. The standard orchestration is the one apparently by the Italian conductor Bernardino Molinari (1880-1952), who conducted the Palestine (and later on Israel) Philharmonic Orchestra on several occasions between 1945 and 1948. Another orchestration by the German-Israeli composer Paul Ben-Haim (1897-1984) is also current.

However, the song did not become officially the national anthem of the State of Israel until November 10, 2004, when it was sanctioned by the Knesset in an amendment to the “Flag and Coat-of-Arms Law” (now called “The Flag, Coat-of-Arms, and National Anthem Law”). The official text of the anthem consists of the first stanza (out of nine) and the (amended) refrain of the original poem by Naftali Herz Imber. We shall discuss this official sanctification below in more detail.

A religious song from West to East

The reception of Hatikvah as a religious song is perhaps one of the most ignored aspects in the dense net of Internet resources about the song. In this context we have to differentiate between two practices: the adaptation of its melody to other religious texts, and the performance of text and music in religious assemblies. Hatikvah appears as a piyyut in countless manuscript collections of sacred songs, sometimes as “piyyut na’eh”, and well as in printed books, especially (and not surprisingly) in Passover haggadot.

We have already seen that apparently the melody of Hatikvah made its inroads into the synagogue by the time of the great cantor Nissi Belzer in the late nineteenth century. But one of the best documented and still used practices is found in religious Zionist families, mostly German, in which there is a tradition of singing Psalm 126 (Shir ha-ma’a lot be-shuv Adonai et shivat-Ziyyon), the opening of the Blessing of the Meal (birkat ha-mazon), on Sabbaths and holidays to the melody of Hatikvah. We have this practice documented as an established one already by 1918.[39] In fact, there was in religious Zionist circles a suggestion to substitute Imber’s text with this “national” Psalm as the Zionist anthem.

A touching anecdote about the persistence of this practice is provided by Ariel Hirshfeld, an Israeli mosaic artist (not to be confused with the writer and professor of literature of the same name also quoted in this essay). Hirshfeld is deaf from birth and expresses his inner world of sound through his artistic creations, testifies the following:

“But it is difficult not to be connected on Friday evening to the Sabbath prayers, and the most difficult part is not being able to take part in Sabbath songs when you sit at the dinner table in your own family's home… As a child, I didn’t sing because I could not. I could not sing with everybody. Now, as a father of five wonderful children, it is not easy for me to sing, because I am out of tune, sing in an unclear melody, and mix together several melodies… Once, my parents were invited as my guests for the Sabbath. At the dinner table, my parents sang and I mumbled something… at least my children will think I sing… At the end of the dinner, before saying the ‘Grace After Meals’, it is accustomed to sing Shir HaMaalot ('Song of Ascents'), and I, as the host, started to sing. Suddenly my father looks at me surprised and asks – “Why?” – “What do you mean by ‘why’?” I replied with a question. “Why do you sing with the melody of HaTikva (the Israeli national anthem)?? It is not appropriate now, and there is no reason to sing it now…” Wow. Without knowing, I sing Hatikva? What an honor, how nice!! So, until this day, I sing Shir Hama’alot with the melody of HaTikva, because this is the only thing I know, and also because it is special to me…[40]

More remarkable, Hatikvah was printed in several collections of Hebrew religious poetry published in the Near East in the first three decades of the 20th century.[41] For this reason it entered Israel Davidson’s canonical catalogue of Hebrew sacred poetry, Otzar ha-shirah ve-ha-piyyut (New York 1929, vol. 2, p. 481, khaf 386).[42] Davidson explains his decision as follows:

“On the other hand, a word of explanation is in place, why the Ha-Tikwah is included. It gained the right for a place among the piyyutim by the simple fact that it has already found its way in some Oriental book of prayers. So let no one deem it an idiosyncrasy on my part, that Naphtali Herz Imber is represented in the Thesaurus, while all the great modern poets are ignored. The plan of the work demanded the inclusion of the one and the exclusion of the others.” (New York 1933, vol. 4, p. xv, English introduction).

Hatikvah was sung in paraliturgical assemblies in Jewish communities of the Eastern Mediterranean. For example, for the meeting of the ‘Hallel ve-zimra’ association of paytanim in Salonika that took place on April 15, 1926, a brochure titled ‘Fasil Nahawand’ with the songs to be performed on that occasion was published. It opens with the lyrics to the Greek anthem and ends with Hatikvah, a reflection of the complicated double allegiance of the Jews of Salonika in the years following its annexation to the modern Greek nation-state.[43] This conjunction between religious and national spheres was characteristic of the former Jewish communities of the Ottoman Empire who found themselves caught in the new national configurations of the post-imperial era. Singing Hatikvah in such religious settings was not necessarily an exclusive act of identification with territorial Zionism but rather an affirmation of transnational Jewish solidarity as an antidote to frequent political upheavals.

In some cases, only the melody was used, set to religious texts, as we have seen in the Ashkenazi practices. The following case shows to what extent the song was part of the musical baggage of Oriental Jews. In 1931, the German composer and photographer Hans Helfritz (1902-1995), a disciple of the great comparative musicologist Erich von Hornbostel arrived to a remote area of Southern Yemen where he recorded Yemenite Jews. Among the songs he recorded was the piyyut ‘Sapperi tama temmima’ sung to the melody of Hatikvah with the refrain ‘Eretz Tziyyon Yerushalayma / Eretz Tziyyon Palestina’. This utmost case shows how widespread our song was through the Middle East.[44]

Even in the present, the singing of Hatikvah in synagogue contexts can be found in every corner of the Jewish world. Hereby follows a testimony from Belgrade: “In synagogue activities that I have attended, a relationship with the State of Israel is rarely expressed, aside from the weekly references to Israel that are a part of prayers, but the rare occasions communicate strong bonds. Sometimes the bonds are expressed musically, for example in the singing of the Israeli national anthem Hatikvah at the conclusion of the Rosh Hashanah community Seder [sic] in 2010.”[45]

However, besides this favorable reception in synagogues throughout the Jewish world there was also staunch resistance to Hatikvah in other religious circles, and not only in anti-Zionist ones. The renowned Torah scholar and thinker Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hacohen Kook (1865–1935), the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of the British Mandatory Palestine and spiritual leader of what became the National Religious Movement, was not sympathetic to the Zionist anthem. As an antidote to Hatikvah Rabbi Kook wrote “Shir ha-emunah” (“The Song of Faith”) following the Balfour Declaration in 1918. She song exists in several versions and with more than one melody. In the notes to the CD ‘Nafshi takshiv shiro: Shirei Harav Kook’ (‘My soul will seek his song: The Songs of Rabbi Kook’, Jeursalem, Gal Paz 2011) Rabbi Eliashiv Berlin recounts:

[‘Shir ha-emunah’] was written in 1929 and published in a chapbook with other songs by Rabbi Kook. In this chapbook published when the Rabbi was still alive, it is written that one has to sing this song to the melody of Hatikvah. This information adds to the assumption that the Rabbi was not at ease with the text of Hatikvah and that he sought to substitute it with ‘Shir ha-emunah’. The motivation of the Rabbi was to add holiness and Jewish content to the national anthem. On 1962 Rabbi Shalom Nathan Raanan asked his students [of the Merkav Harav Yeshivah] to find a tune for the song. Rabbi Israel Ariel who studied at the time at the yeshivah proposed to sing it to the tune of ‘Harninu goyim ‘amo’ [Deuteronomy 32, 43] and since then this tune became the widespread melody for ‘Shir ha-emunah’. One has to point out that there are several versions of the text, but this version [in the CD] was sanctioned by [the Rabbi’s son] Harav Tzvi Yehudah Kook as the correct version and was printed in the Siddur [prayer book] ‘Olat re’ayiah’… The song appears there after the order of Hakafot to Simhat Torah [Rejoicing of the Torah].

In the collection ‘Mivhar shirei ‘amenu’ (‘Selection of Our People’s Songs’, Berlin-Vienna: Menorah, 193?) ‘Shir ha-emunah’ appears printed, apparently for the first time, immediately after Hatikvah and under its title is written ‘[sing] to the melody of Hatikvah’ In spite of this clue, it appears that Rabbi Kook’s song was generally not sung to the tune of Hatikvah and for this reason new melodies where sought by the Rabbi’s disciples. According to Rabbi Eliashiv Berlin, among the concepts that Rabbi Kook disagreed with in Hatikvah was the word “hofshi” (“free” or “independent”) in the verse ‘to be a free people in our Land’. The Rabbi feared an interpretation of this verse as “to be secular in our Land” in the sense of “free form the yoke of the Torah”. Rabbi Kook’s poem indeed paraphrases Hatikvah but with a deep theological twist: “steadfast faith in the return to our holy land…where we shall serve our God.”[46]

This challenge to Hatikvah by the undisputed spiritual leader of the National Religious Movement shows how volatile and complex the reception and reading of this song was in diverse religious circles. In fact, one may argue Rabbi Kook’s contestation against the national anthem already in 1929 was a harbinger of the future challenges to the Israeli state, its institutions and symbols by extremist circles that follow Rabbi Kook’s activist messianic theology.

But resistance to Hatikvah was not only coming from religious circles. In the 1930s there was a propensity by socialist Zionists to replace it with Haim N. Bialik’s ‘Birkat ‘am’ (aka. ‘Tehezakena’), precisely because of Hatikvah’s suspicious messianic overtones and Biblical rhetoric. As we have seen above, ‘Tehezakena’ was a serious competitor of Hatikvah for the position of national anthem from the moment both songs spread in the last decade of the nineteenth century in Palestine and throughout the Jewish world. The powerful Histadrut (Worker’s Union in Palestine) utilized Bialik’s song (and the red rather than blue and white flag) in its celebratory rituals during the peak of its power in the 1930s. The characteristically assertive, chordal, marching, major (one is tempted to say ‘masculine’) Russian tune of ‘Tekezakena’ had a contrasting sonic signification in comparison to the minor, stepwise, ‘femenine’ melody of Hatikvah.[47] Therefore, not only textual but also musical considerations played into this competition between the advocates of each of these two songs.

Hatikvah among Jewish art music composers

We have already shown that the earliest version of Hatikvah with musical notation appeared in an arrangement for voice and piano by cantor Friedland from Breslau in 1895 in the form of a lied. As is gained popularity outside of Palestine, European composers continued to arrange Hatikvah as a lied, attempting to color it with alternative harmonic interpretations as a way of adding personal interpretative dimensions to the song.

A fascinating case of such an arrangement is Efraim Shkliar’s. Shkliar (or Schkljar, 1871-1943) was one of the composers associated with the national school of Jewish music in Russia at the beginning of the twentieth century. His arrangement dates back to 1910 and was analyzed by James Loeffler as an example of what he calls the “modern political song.” Shkliar’s attempt, as Loeffler has shown, tries to avoid “an Eastern European folk song, Jewish or otherwise,” and resembles “a nineteenth-century central European synagogue chorale in the German Protestant tradition.” What is more interesting and relevant to us here is that Shkliar’s arrangement was severely criticized by no less than Joel Engel and Mikhail Gnesin, two towering figures of the Russian Jewish school.

Engel’s dictum was that the melody is “entirely unsuitable for a national anthem.” It lacks any typical “Jewishness,” and furthermore, Engel claims, it resembles a Ukrainian folk song (this observation came many years before Idelsohn noticed it), and it is in a minor, pessimistic character. Engel’s critique is remarkable, for it identically matches the negative views held by many members of the Zionist movement, Herzl included, towards Hatikvah. Gnesin, on the other hand, opposed the haphazard arrangement of monophonic Eastern European Jewish “folksongs” (his own categorization of the Zionist anthem).[48]

At this point, one must notice that the “foreignness” for which Hatikvah was criticized by Engel and others is precisely the source of its resilience. This is Ariel Hirschfeld’s main argument: “It was its resistance to Zionism’s optimism that made it attractive. The song is deeply subversive: we have not arrived at Zion and have never been a free nation in its own land.” He stresses reception over conception as the social mechanism of canonization: “Its selection as the national anthem was not an ideological gesture so much as a response to the hosts of singers that identified so deeply with it and valued it so dearly.” Finally, Hirschfeld repeats an argument that he has proposed for the modern Hebrew song in general: “This ambiguity [between the messages conveyed by text and music] is rarely as plainly visible as in the case of ‘Hatikvah,’ the lyrics of which…speak of a movement forward and Eastward (kadimah) while the melody expresses a nostalgic gaze backward (kedem).”[49]

Interestingly, the argument regarding the “un-Jewishness” of the melody of Hatikvah reappears in the opinion of one of Russia’s most eminent artists of the early twentieth century, the renowned opera singer and actor Feodor Chaliapin. During his American tour of 1924-5, the following report appeared in a Jewish newspaper:

Chaliapin is susceptible not only to Jewish cooking, but also to the charms of Jewish music. During the Revolution, in 1919 [sic], [journalist and writer] Herman Bernstein [1876-1935] happened to be in Petrograd. He was invited by the great basso [Chaliapin] to stay in his beautiful home on the Kammenoi-Ostrovsky Prospekt. In those days it was not safe for anyone –not even for such a popular favorite as Chaliapin - to travel unguarded through the streets, so a car, armored and provided with a number of soldiers and sailors as escort, carried the singer and guests to and from the opera house. After the concert for the Zionists, at which Chaliapin was wildly applauded for his singing of ‘Hatikvah’ he came home and played and sang a number of Jewish folk-songs.

“‘Hatikvah’ is all very well,” [Chaliapin] said [in this American interview] “but in my opinion it is a ‘made’ anthem. It is not a true national song. A song like ‘Af’n Pripetchick,’ [sic] for example, is really characteristic of Jewish life in Europe, and full of Jewish feeling. The melody is like the voice of a whole people. Why should it not be the national song?’ And in this opinion, many will agree with him.[50]

Hatikvah as a popular song: Commercial recordings and sheet music

Hatikvah is perceived today as a national anthem of a movement or a state and therefore its publication as a patriotic folksong in Zionist song collections for youth movements or Hebrewist educational songsters, such as the one by Idelsohn in 1912 (see note 21 above), is generally emphasized by scholars. Yet, its distribution in the early twentieth century was also similar to that of popular songs, namely through sheet music and commercial recordings.

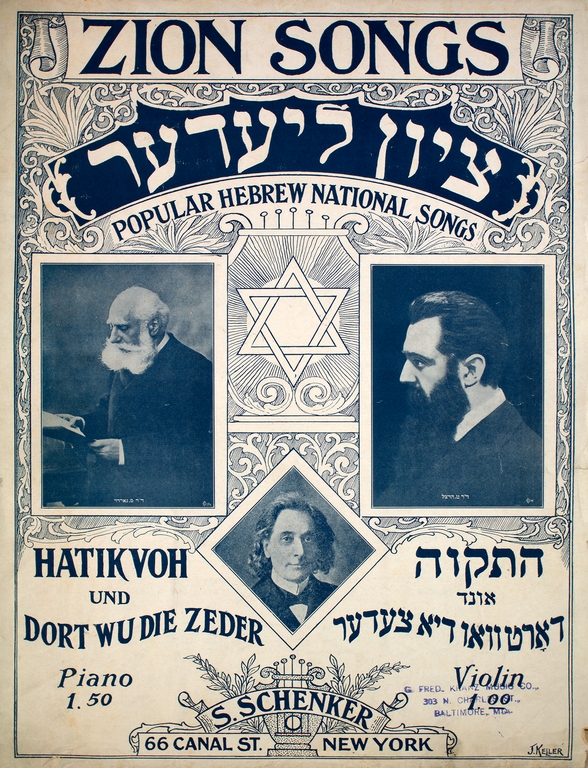

Sheet music was a medium characteristic of the New York Tin-Pan-Alley scene and Hatikvah appeared in several arrangements for the consumption of the massive population of Eastern European Jewish immigrants in the Big Apple. A widespread arrangement for voice and piano was by A. R. Zagler (arranger), in a sheet titled ‘Zion Songs: Popular Hebrew National Songs’ that included another Zionist anthem that seriously contested Hatikvah, ‘Dort wo die Zeder.’ This publication, published in 1912 by Saul Schenker, erroneously credits the text and music of Hatikvah to ‘L.N. Imber’.[51]

Zion Songs: Popular Hebrew National Songs title page

First page of Hatikvah score from Zion Songs: Popular Hebrew National Songs

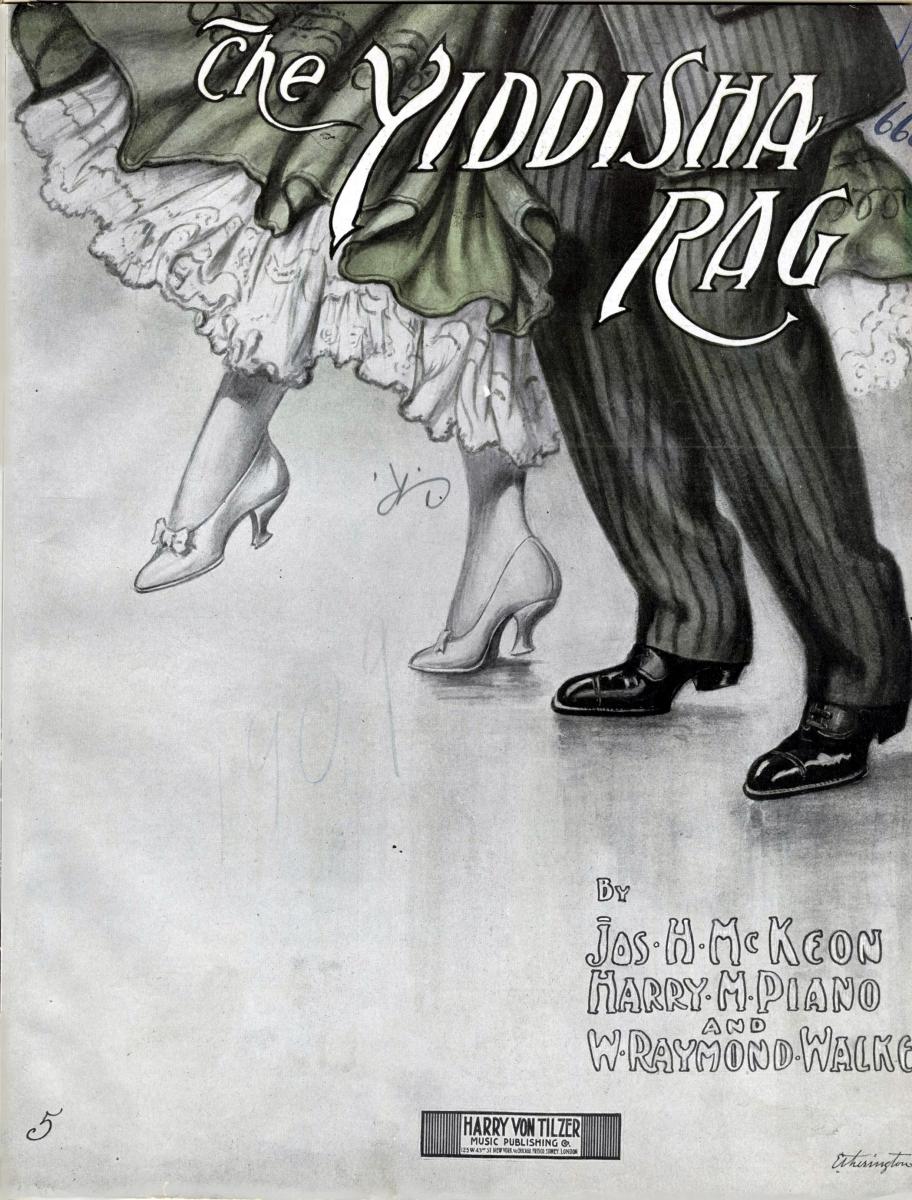

Not only full Tin Pan Alley arrangements of Hatikvah appeared early on, but also fragments of its melody were quoted, as a “lick,” in popular songs of the early twentieth century. One of the earliest of such quotations appears in the ‘Yiddisha Rag’ (Joseph H. McHeon, Harry M. Piano and W. Raymond Walker, 1909). This song employs the first two bars of Hatikvah in the bridge section, but also uses the characteristic jump of an octave at the beginning of the second part (‘od lo avda tikvatenu) followed by a step-wise descending line in the first part of the melody.[52]

The Yiddisha Rag title page

The greatest technological breakthrough in the history of sound, the gramophone, unquestionably facilitated the rapid spread of Hatikvah throughout the Jewish Diaspora. The immediate recruitment of this new technology of sound reproduction by Jews is utterly remarkable. The logic of the early recording industry was based on catching on wax the repertoires that were well established among the masses attending the live stages and making them available for the household.

Most of the early performers of Hatikvah in commercial recordings were by synagogue cantors rather than stage singers, a further testimony of the sacralization of this anthem in its early stages of existence. Hatikvah was recorded for the first time (as far as we know today) in Warsaw in 1902, hardly two decades after its conception by Samuel Cohen in Rishon Le-Tziyyon, by a certain Cantor Kipnis.[53] It is very possible that “Cantor Kipnis” may have been Menachem Kipnis (1878-1942), the celebrated Yiddish folklorist, pioneer photographer, humorist and singer, but perhaps also his older brother and mentor, known as Peysy or Peyse the Cantor. Around the time this recording was made, Menachem was a young tenor chorister at the Great Tłomackie Street Synagogue in Warsaw.[54]

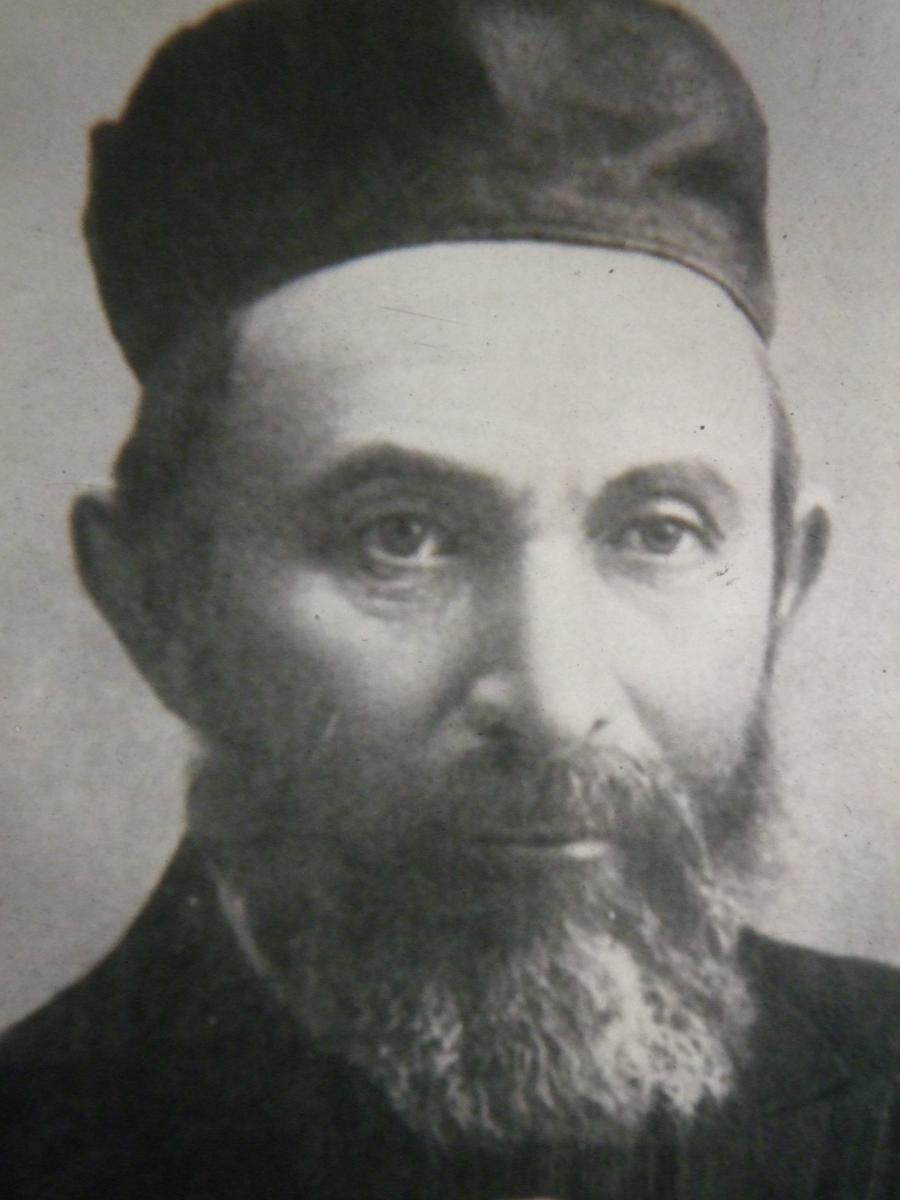

Menachem Kipnis

The first American recording of Hatikvah (again, as far as we know at this moment) was probably the work of Solomon Shmulewitz-Small (1868-1943), a Yiddish poet, playwright, composer, and folk singer born in Pinsk, Byelorussia, who came to the United States in 1891. He recorded the song for the Zonophon Company in New York in 1904 (the recording does not carry Shmulewitz’s name but the other cuts in the series of recordings on the same day contains his name).[55] These early cantorial recordings of Hatikvah launched a trend in which the greatest American hazzanim cum opera singers of the twentieth century could not avoid but record it, as evidenced by the performances of Al Jolson, Jan Pierce and Richard Tucker.

Not only in Western Europe and in the United States was Hatikvah recorded in the earlier days of the recording industry. As early as May 1907 it was pressed (also by the Zonophone Company) by the Sephardic tamburitza (long neck lute) ensemble and choir ‘La Gloria’ in Sarajevo.[56] The recording industry in the Eastern Mediterranean also offers evidence of the status of Hatikvah as a piyyut that we have discussed above. Two of the greatest Ottoman/Turkish singers/cantors, Isaac Algazi and Haim Effendi included it in their recordings’ catalogue of cantorial pieces next to songs in Ladino and Turkish.[57]

One Song, Many Memories