Hayrana Laih is an Egyptian song that was and still is popular in the Arab world, but also has connections to Jewish musical contexts and musicians. The lyrics of Hayrana Laih were written by Ahmed Rami (1892-1981), the popular Egyptian poet who was the main songwriter for Umm Kalthoum. Daoud Hosni (1870-1937), an Egyptian composer of Karaite Jewish origins composed it in 1932 for the Egyptian singer of Jewish extraction, Leila (or Layla) Mourad (1918-1995).

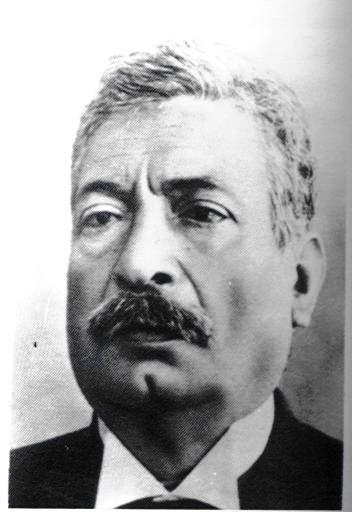

Daoud Hosni (whose Hebrew name was David Khadr Hayyim Halevy or David Hayyim Eliyahu Levy) was a Karaite Jew born in Cairo near the Karaite quarter. He was initially recognized as a singer and ‘ud player, but his wide popularity stem from the popular songs he composed (more than five hundred), which he wrote for Egypt’s most popular singers of the time, such as Umm Kalthoum and Amal El-Atrash (Asmahan). Besides popular songs, Hosni composed operettas, and is recognized as the first Arab composer to write an opera in Arabic (Samson and Delilah). He enriched Arab music by introducing new modes (maqamat) and rhythms of Persian and Turkish origin.[1] Daoud Hosni played a fundamental role in the creation of the Egypt’s modern music, and was a colleague of major composers such as Sayyed Darwish and Zakariyya Ahmad. In the 1932 Cairo Music Conference he was recognized as a leading figure of modern Egyptian music.[2] His songs and compositions were played across the Arab world, and are still performed and remembered today.

The memorialization of Daoud Hosni is a matter of contention. His Karaite Jewish origin was generally forgotten and only the popularity of his music has remained in the memory of Arab song lovers. Yet, a memorial page for Daoud Hosni in the website of the Historical Association of Egyptian Jews that is based on information provided by the composer’s two children maintains that his Karaite Jewish origin played against him throughout his career, for example in being denied the position of director of the “Egyptian Theater.”[3] This website stresses the “Jewishness” of Hosni that was expressed, according to the testimonies included in the commemorative text, by the composer himself. To what extent such perceptions are accurate is still to be clarified. The son of Hosni, the journalist Yitzhak Levy, still lives in Israel as does a substantial contingent of the Egyptian Karaite Jewish diaspora. In Levy’s perception, his father was forgotten in Israel, where his music is unknown, while in Egypt his work is still cherished.[4] To substantiate the “Jewishness” of Hosni, Joseph Algazi maintains that the composer set music to Hebrew songs but he does not provide evidence, except for the Karaite anthem in Hebrew “Ba-esh navo uba-mayyim” (By fire we shall come and by water). This poem was written by the spiritual leader of the Egyptian Karaites at the time of Hosni, Hakham Tuviyah Sikmha Levy Babovitch.[5]

The memorialization of Daoud Hosni is a matter of contention. His Karaite Jewish origin was generally forgotten and only the popularity of his music has remained in the memory of Arab song lovers. Yet, a memorial page for Daoud Hosni in the website of the Historical Association of Egyptian Jews that is based on information provided by the composer’s two children maintains that his Karaite Jewish origin played against him throughout his career, for example in being denied the position of director of the “Egyptian Theater.”[3] This website stresses the “Jewishness” of Hosni that was expressed, according to the testimonies included in the commemorative text, by the composer himself. To what extent such perceptions are accurate is still to be clarified. The son of Hosni, the journalist Yitzhak Levy, still lives in Israel as does a substantial contingent of the Egyptian Karaite Jewish diaspora. In Levy’s perception, his father was forgotten in Israel, where his music is unknown, while in Egypt his work is still cherished.[4] To substantiate the “Jewishness” of Hosni, Joseph Algazi maintains that the composer set music to Hebrew songs but he does not provide evidence, except for the Karaite anthem in Hebrew “Ba-esh navo uba-mayyim” (By fire we shall come and by water). This poem was written by the spiritual leader of the Egyptian Karaites at the time of Hosni, Hakham Tuviyah Sikmha Levy Babovitch.[5]

Daoud Hosni composed Hayrana Laih in 1932, five years before his death for a then young Egyptian Jewish singer, Leila Mourad. It was to be her first recorded song and her first step in her way to stardom, like Hosni, in the Arab world. For the next two decades she competed with the great Umm Kalthoum for the primacy of the female Egyptian singing stage.

Layla Mourad, was born in Cairo as Lilyan Mordecai to a Jewish family of Iraqi decent. Her father, Zaki Mourad was a famous musician in Egypt. He was also a synagogue cantor and composer.[6] After recording her first song at the age of 14, Layla appeared in concerts across the country. She was “discovered” in 1938 by Mohammad Abd al-Wahhab who invited her to co-star in his film “Yahya al Hub” (Long Live Love). From this point on she gained enormous popularity, mainly as a movie star, and the attention of leading Egyptian composers of the time who wrote songs for her, like Mohammad al-Qasabgi and Riyad al-Sunbati, who also wrote for Umm Kalthoum. In 1945 she married the actor Anwar Wagdi, who co-starred with her in several movies. Under his influence she converted to Islam in 1947; they were divorced in 1951.

Mourad was highly appreciated by Gamal Abdel Nasser, who led the Egyptian revolution in 1952, and was named by the mass media as the “queen” of the revolution. Yet, shortly after, rumors spread -probably by her ex-husband Wagdi- about Mourad donating money to the State of Israel. Consequently, her music was boycotted in many Arab countries. Ultimately she was able to deny these rumors. Yet, these events had an emotional effect on her and in 1955, though still enjoying a wide popularity, she retired from acting and several years later also from singing.[7]

Mourad was highly appreciated by Gamal Abdel Nasser, who led the Egyptian revolution in 1952, and was named by the mass media as the “queen” of the revolution. Yet, shortly after, rumors spread -probably by her ex-husband Wagdi- about Mourad donating money to the State of Israel. Consequently, her music was boycotted in many Arab countries. Ultimately she was able to deny these rumors. Yet, these events had an emotional effect on her and in 1955, though still enjoying a wide popularity, she retired from acting and several years later also from singing.[7]

Until her death in 1995, Mourad made rare public appearances. She sang more than 1,000 songs and appeared in twenty-seven films. Her songs are performed until the present and she is remembered as the first Arab lady of the Egyptian cinema. In 2009, a joint Egyptian-Syrian TV series about Mourad's life, “Ana Albi Dalili,” was broadcast in the Arab world.[8]

Hosni and Mourad are members of two consecutive generations of modern Egyptians covering a crucial and turbulent period in the history of Egypt and its Jews. Their story shows the extent of integration of many Jews and Karaites into the Egyptian social fabric, most especially in the entertainment industry, a phenomenon found in other Arab countries.[9] However, the difference of one generation between these two artists of Jewish origin sealed their different fates. Hosni died in Egypt at the peak of his fame and of Egypt’s late colonial blooming, prior to the establishment of Israel and the 1952 revolution and was buried in his homeland as a Karaite Jew. Laila Mourad on the other hand lived in Egypt until the end of the twentieth century. We assume that her decision to abandon Judaism was due not only to the influence of her Muslim husband, but also out of necessity. In post 1948 and 1952 Egypt, she could only succeed and live peacefully as a Muslim. Despite her Egyptian patriotism and Islamic religion, her Jewish origin lingered on her, eventually bringing her career to an end. On the other hand, one can also imagine what her future would have been had she decided to remain Jewish and immigrate with her family to Israel. Perhaps she would have been forgotten in a ma’abara (immigrants’ transitional camp) like other prominent musicians from Arab countries who immigrated to Israel. A twenty-first century awakening in the interest on the cultural heritage of Jews from the Arab world in Israel and elsewhere has created a flurry of Internet discussions about Layla Mourad written by Jews in Hebrew and other languages.

The next “Song of the Month” will be dedicated to the piyyut Hai Ram Galeh, which stems from Hayrana Laih, taking us from Egypt to Israel, from Arabic to Hebrew, from the secular space to the religious one, and from the vast popularity of the song to a more restricted context of performance.

|

Translation

Why are you undecided? You’ve made my heart melt Why are you undecided?

I’ve accepted your indifference obediently And I’ve spent many nights alone, my nights becoming longer. Why won’t you have mercy on him? Why do you torture him? The heart submits to beauty

What does it matter that my heart is unlike yours Enslaved with your love from the day I saw you No matter how indifferent or commiserating you are with him He is in your hands subjugated to your orders

Only once the heart loves and is satisfied And my heart, by God, has gotten used to affection You who dwells in it, why do you cause it pain Submit to your lover, don’t resist Why are you undecided? Why? |

Transliteration

H’ayranah laih bein el-ouloob Khalleite aalbi rah’ yidoob H’ayrana laih bein el-ouloob

Radait gafaki b-emtithal W-s-herti wah’di w-leili tal Mosh tirh’ameeh! Laih Ta’athibeeh Da-l-albi khadee’ l-el-gamal

Esh maa’na aalbi mosh zayyi albek Aasi b-hawaki men yom ma shoftek Mahma tgafeeh walla twaseeh Ma bein yadeki khadee’ le-amrek

El-albi marra yee’shaa we-yirda W-albi wallah akhad a’a-lmawadda Ya sakna feeh laih teelimeeh Waffi l-h’abeebek balash minahda H’ayrana Laih bain el-ouloob H’ayrana laih |

Source

حيرانة ليه بين القلوب خليتِ قلبي رح يدوب حيرانة ليه بين القلوب

رضيت جفاكِ بامتثـال وسهرت وحدي وليلي طال مش ترحميه ! ليه تعذبيه ؟ ده القلب خاضع للجمال

ايشمعنى قلبي مش زي قلبك قاسي بهواكِ من يوم ما شفتك مهما تجافيه والا تواسيه ما بين ايديك خاضع لأمرك

القلب مرة يعشق و يرضى وقلبي والله اخد ع المودة يا ساكنة فيه ليه تؤلميه وفي لحبيبك بلاش مناهدة حيرانة ليه بين القلوب حيرانة ليــه |

[1] David Marzouk, Abe Mourad and Albert Gamil, “The Commemoration of Daoud Hosni.”. In: http://www.hsje.org/comdaoudhosn.htm. Accessed May 5, 2013.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Joseph Algazi, “Kasheh Lihiyot Kara'i Be'Israel.' (It is difficult to be a Karaite in Israel) 5.9.1997. In: http://www.defeatist-diary.com/index.asp?p=memories_new10024&period=10/1.... Accessed May 5, 2013.

[5] “The Commemoration of Daoud Hosni,” note 1 above.

[6] Recordings of some High Holiday selections performed by Zaki Mourad circulate in the Internet from recordings that were kept in the family in Egypt. See for example: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cgfp9Whxp3U&lr=1; http://www.zamanalwasl.net/forums/showthread.php?t=4479.

[7] Joel Beinin, “Layla Murad: Popular Culture and the Politics of Ethnoreligious Identity,” in The Dispersion of Egyptian Jewry: Culture, Politics, and the Formation of a Modern Diaspora. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2290045n/

[8] Sami Asmar, “Decade Later, Layla Murad Still Unforgettable Artist,” Al Jadid: A Review and Record of Arab Culture and the Arts 11 (2005), nos. 50/51: http://www.aljadid.com/content/decade-later-layla-murad-still-unforgettable-artist. Accessed May 5, 2013; Eyal Sagui Bizawe, “The return of Cinderella,” Haaretz Online (October 1, 2009): http://www.haaretz.com/the-return-of-cinderella-1.6862. Accessed May 5, 2013.

[9] For a review of this phenomenon see, Edwin Seroussi, “Music,” Encyclopedia of the Jews in the Land of Islam vol. 3 (2010), pp. 498-519.