This document, in the form of a synoptic table, incorporates three versions of Idelsohn’s autobiography. The original table is available in table format as a PDF download here, and at the bottom of the page. In the present HTML version the table has been formatted as a linear text for easy online search and mobile viewing.

Idelsohn's Hebrew and English biographies, written in the early 1930s, appeared in 1935. The English one was published in Jewish Music Journal 2, no. 2 (1935): 8-11. The Hebrew one appeared in Die Chasanim Welt 3, no. 15, (Sh’vat, 5695, January 1935): 22-23 and is translated here to English. Both were reprinted in their original language in Idelsohn’s memorial volume, Yuval 5 (1986). These two accounts differ in their length and in some details. A third, partial autobiography in German was located in 2017 in a batch of uncatalogued Idelsohniana located at the library of the Hebrew Union College (HUC) in New York City. This German text provides insights into Idelsohn’s ancestors lacking from the English and Hebrew autobiographies. As far as we know, the German biography that stops at Idelsohn’s adolescence remained unfinished and unpublished. We are deeply thankful for the HUC Library’s director, Yoram Bitton, for his assistance in locating and digitizing this and other Idelsohn documents. We are also thankful to Shoshana Liessman for the translation of the German text into English.

In this table, we have attempted to align synoptically the different events in Idelsohn’s life as he related them in the different versions of his autobiography. Such an alignment provides insights into Idelsohn’s displaying of the events of his life to diverse audiences. To complete this synoptic autobiography we added selections of the recorded memoire of Idelsohn’s younger daughter, Yiska. This document remained in possession of the family’s heirs in South Africa. It was digitized on our behalf by Idelsohn’s great-grandson, Jonathan Misha Morgan. Jonathan has become the curator of his great-grandfather’s legacy in South Africa and we are extremely grateful to him for his dedication and assistance to our work.

We have included in the table selections of Yiska’s memoire whenever they are relevant to Idelsohn’s own account. They do not appear in the order of their recording. Therefore, we have marked their position in the original sequence with bracketed numbers. Jonathan’s voice relating to Yiska’s utterances is also included in this document. We have differentiated his voice from Yiska’s direct testimony by writing the later in italics. In addition, we have added a few footnotes clarifying details of places, institutions and people mentioned by Idelsohn. Notice that the members of the family refer to Idelsohn throughout their correspondence with the term of endearment 'AZ' (Abraham Zevi).

This table must be read in conjunction with another document that we are publishing in the Idelsohn Project page in this website, the memoire of Idelsohn's daughter Shoshana. These combined documents provide the most accurate timeline of Idelsohn’s family life that we possess at this point. Further readings of primary documents will certainly allow for a more refined future version of this document.

Notice: this is a work in progress and is being updated from time to time. Please do not copy or reproduce without previous consent of the authors. Photographs from the Idelsohn Archive (numbered MUS 0004) are reproduced here courtesy of the Israel National Library. They are property of the Israel National Library and cannot be reproduced without the proper consent of this institution.

Family Background

German version:

My grandfather was a coppersmith in Wekschny [Viekšniai or Vėikšnē, city in the Mažeikiai district municipality located 17 km south-east of Mažeikiai], Semogalen [i.e in the district of Samogitian in northwestern Lithuania] who had to give up his trade and hide because he was wrongfully convicted by the Czarist government. He lived as a hermit in an abandoned water mill separated from his family, where he dedicated himself to Kabbala and died at the age of 34 after several years of self-mortification and midnight prayers.

My father, orphaned at the age of twelve, had to wander from one yeshiva to the next through Lithuania and Poland, educating and feeding himself. Finally, he ended up becoming a shohet, teacher and prayer leader in Kurland, the El Dorado of Lithuania. There he married the daughter of a distiller at a German Estate. My mother knew German which she acquired by the special favor of the Duke who allowed her, as the only Jewish pupil, to visit his German primary school. All her siblings remained illiterate; with great effort, the brothers learnt to draw their names in Latin letters and with even greater effort they learnt to spell out some prayers in Hebrew. Nevertheless, they became proficient traders.

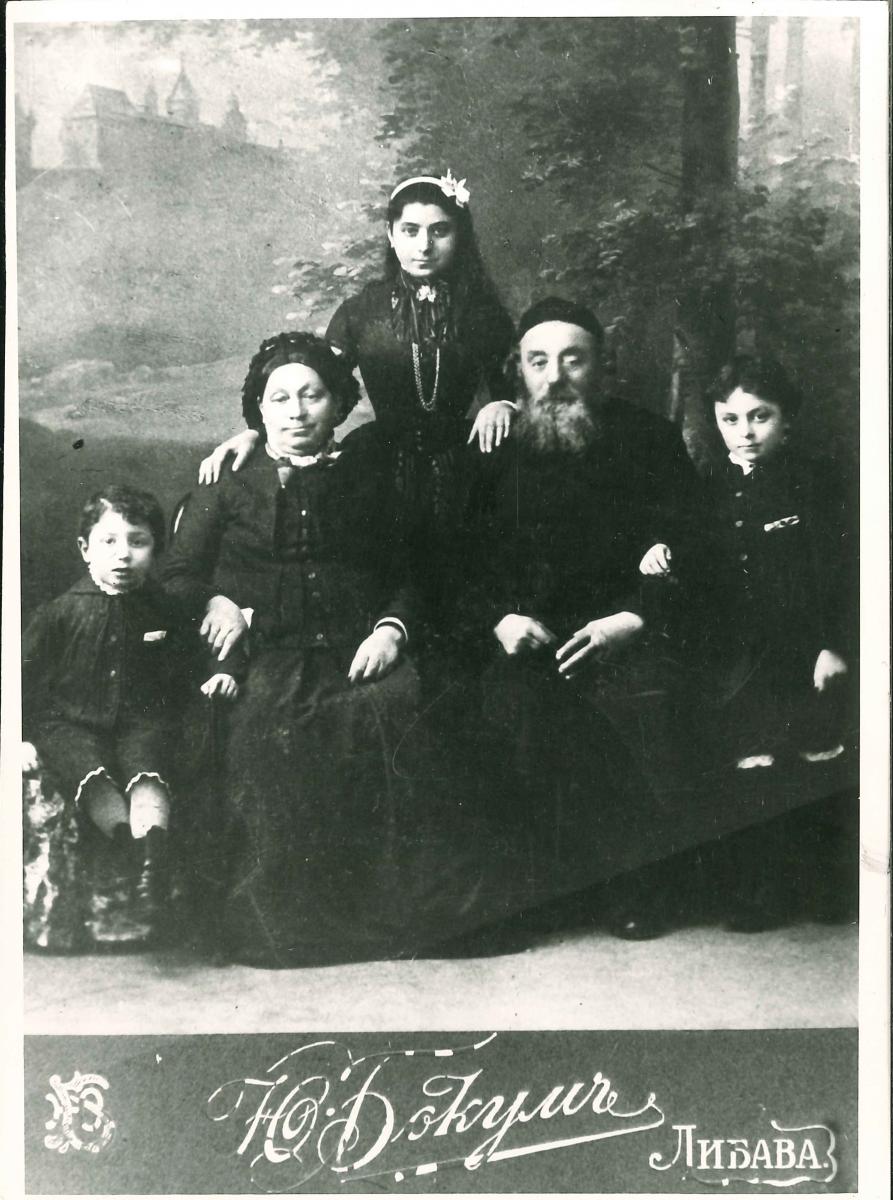

From right to left: A.Z. Idelsohn at age 6-7; his grandfather Yosef Hirshfeld; his aunt Feile; his grandmother Batsheva Hirshfeld; his cousin Yitchak Hirshfeld. (MUS 0004 K 01_1).

Birth, the parents, early childhood in Libau (1883-1895) and yeshiva studies in Zamut (1895-1900)

English version:

I was born in the fisher-hamlet Phoelixburg, on the Baltic Sea, between Windau and Sackenhausen, Latvia. My father was Schochet and Baal-t’filloh in the district. When I was less than six months old, my parents moved to Libau,[1] where, due to the efforts of Dr. Philip Klein, then Rabbi in Libau (later in New York), my father was appointed overseer of kosher meat in a non-Jewish butchery.

In my early childhood my parents lived next to the “Chor-shul” and my father used to take me over to that cold, unheated house of worship. The chazan was Abraham Mordecai Rabinovitz. His strong tenor-voice used to chill me; he had no sweetness in his voice. I remember the Congregation preferred to hear Zalman Shochet, though very old, or Orkin of the Zamet Synagogue.[2] Little did I realize that Rabinovitz will later become my teacher. The above mentioned cantors had less voice than he, but much sweeter, and their singing was with more Jewish feeling.

From my father I learned to love the synagogal modes and “Zemiroth” as well as Jewish Folk-Songs. At home I received an orthodox education and appreciation for everything Jewish. I visited old-fashioned “Chadorim,” although there were many modern ones in Libau; my father wanted to implant within me the genuine Jewish piety. At the age of 12 years, I was sent to Lithuanian jeshivas, where I remained five years. During that period I acquired a knowledge of Jewish life. Upon my return home, I decided to take an examination in the Gymnasium and prepare for an intelligent profession.[3] I secured a tutor and started studying.

Hebrew version:

I was born in the fisher-hamlet Felixberg,[4] on the Baltic Sea, between Windau and Sackenhausen, in the province of Courland in Latvia. My father was a schochet and baal-t’filloh in the district. I was born on 24th of Sivan 5642 [11 June 1882], but my birthdate was listed in the registry as July 2, 1882. When I was six months old, my parents moved their residence to the city of Libau where I received my education in the chadorim[5] until my twelfth year. Then my father sent me to various yeshivoth in Zamut[6] where I remained five years.

Upon my return to Libau, I began preparing subjects studied in the Gymnasium, and so without my father's knowledge, I joined the choir of the magnificent Chazzan Mordecai Rabinovitz and he took upon himself to teach me the music theory and voice training.

Yiska’s memoire:

[3a] He was born in Latvia, near Libau, in a town called Felixburg which was renamed Kurland by the Russians.

[2] Yiska's dad's dad was Azriel Idelsohn. He was born in Felixburg, Libau on the Latvia-Prussian border. He was a Chasid and a Ba'al Tefilah, one who chants when the Torah is read from and a shochet, a ritual slaughterer of animals. He was a very quiet man, very strict with his sons except for Avram Zvi, the second born and the first son, who was protected from Azriel by his mother Devora Leah. Azriel hardly made a living, when they came to South Africa, Devora Leah opened a boarding house in Doornfontein which she kept for years till she fell ill. […] They came to SA in 1912 when they were both in their 50s […] In Latvia she [Devora Leah, Azriel's wife] supplemented her husband's meager shochet income by helping people emigrate to the USA and the UK for a fee. She learned to write German.

[3b] As a child his father Azriel took him to synagogue to sing every day and not only on Sabbath and high holidays.

German version:

I was born in Filsburg (Kurland), a fishing village on the Baltic Sea, on the 26th of Sivan, 1882 [13 June 1882].

My parents were smoked fish mongers, but were soon to move to Libau (Kurland) where my father found employment as a supervisor for kosher meat with a Christian butcher, and functioned as a ba’al kore and shachris [morning] prayer leader. He had a voice that back then [it] sounded beautiful to me, loved singing and had a very good musical memory, excellent for remembering melodies that he used to fit to the texts of the zemiros [Sabbath table songs] and to recycle them over the course of many hours on the Sabbath. I had to repeat those melodies even before I had learnt how to read. Later I found out, that they were [tunes of] Polish folksongs or Hussar [cavalry] marches. The local as well as the visiting prayer leaders found a faithful listener in my father and [I] was always dragged into the crowds. I have to admit that I liked least the singing of the choral-cantor and his choir, to me it sounded too cold and the strict rhythm of the Sulzerian songs [Salomon Sulzer] had an effect similar to that of the music from the neighboring barrack of the Hussar regiment.

At first, I spoke Latvian that was later on replaced by the Jewish-German dialect [Yiddish] in its Kurlandian variant. Although, Libau was a modern city with German culture, my father picked for me a Lithuanian teacher in a Lithuanian-type cheder despite my mother’s protesting who wanted to send me to a German school so that I should become a “Doctor.” I never stayed more than a semester in any [of these] cheders, and sometimes, I already deserted from the melamed [instructor] and his lash after a few weeks to find refuge with my mother.

Until I was 11, I wasted time in such institutions where I studied a bit of Bible and Talmud. Then I was brought to a hermit (porush [Heb. parush]) in a Beshamidrash [Heb. Beit Midrash, rabbinical academy], who introduced me to the pilpul technique of [learning] the Talmud.

Since my father never earned enough money to feed his family, my mother started a dairy shop and I was hired by the age of 8 to carry the milk bottles and was paid about a penny per bottle by my mother. Later on, my mother exchanged this business for a private eatery and I became a waiter and a cashier, with two percent of the gross profit share and had the right to sell beer to the customers. I bought a savings box but my income, no matter how high, turned into loans to my mother…Since my premature business life displeased [my father], he sent me off to his hometown to attend the local Yeshiva; I was 12 years old.

Libau early 1900

English version:

Suddenly I felt an inner call for music and went to the above mentioned Rabinovitz, who accepted me in his choir. There I remained for a half year, despite my father’s protest that I shall become a “Chor-chazan.' His uncle never entered the Chor-shul because of the ban the ultra-orthodox Rabbis laid upon it when it was built.

Yiska’s memoir:

[3c] His great devotion was to Chasidic music. He sang in choirs and travelled as a young man and one day he met a great rabbi who told him that he was in the wrong place and that he should go to Berlin.

[3d] He sang in a choir tunes that were not to his liking of and finally found Hillel [Schneider in Leipzig] who became his master. From there AZ gave 30 years of his best life to his research.

Konigsberg summer 1900

English version:

Due to my brother-in-law, who came to visit us, but had to stop in Prussia, because he had no legal right to enter Russia, we journeyed there to see him. While in Memel (then Prussia), the idea came to me to go to Konigsberg, to Eduard Birnbaum. He accepted me and recommended me to the director of the Conservatory.

At that time I knew nothing of Birnbaum’s work, all I knew was that he was the successor to the famous Weintraub. I found him steeped in German music, his voice insignificant, his chazanuth unappealing and not Jewish. I visited him only a few times; he never instructed me and never showed me his collection.[7]

Hebrew version:

After spending more than half a year with him, I listened to advice from friends and went to Konigsberg to the Chazzan Eduard Birnbaum and began to sing in his choir and also enrolled in the conservatory there.

London autumn 1900

English version:

After a few months I decided to proceed to London, according to my brother-in-law’s advice. Reaching London, I was advised to see several choir-leaders, but did not accept any position. In one case I simply abandoned the place and gave opportunity to another poor singer. I wanted to enter the Jewish College, but I had nobody to guarantee my upkeep during my stay there, so my meeting with Dr. M. Friedlaender was of no consequence. My parents wrote me, that Rabinovitz was willing to take me back, but I had no means to return.

In my distress I turned to Israel Zangwill for help. He recommended me to the Board of Guardians and secured my passage home. Upon Zangwill’s question, how can I return to Russia, where Jews are so maltreated, I answered that I prefer to be with my brothers even in a place like Russia than to live in a free country like England and assimilate.

Hebrew version:

After four months, I left Konigsberg and went, on advice of relatives, to London intending to enroll at the Jews’ College where I would begin to study English. However, I was unable to study at the College because I had nobody to guarantee my upkeep.

In my distress, I turned to Israel Zangwill for help. He indeed promised to help me, but my parents insisted that I return to Libau. Upon Zangwill’s wonder that a Jew would want to return to Russia, a wretched place for Jews, I replied to him that I prefer to be with my brothers anywhere, even in a place like Russia, and so I returned to Libau and again joined Rabinovitz's choir and sang with him more than a year.

Return to Libau, autumn 1900-spring 1901

English version:

Rabinovitz promised to instruct me in Chazanuth and in European music, and he kept his promise. During that year I again sang in his choir. He taught me a lot of things, such as sight singing, theory, voice-training and the beginning of harmony. He acquainted me with the Chazanic literature of Weintraub, Sulzer, Lewandowski and others. He implanted within me an appreciation for good Jewish melodic taste and he gave me also an idea of classic music from the works of Bach, Haendel, Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, etc. At the same time I was an ardent reader of modern Hebrew literature, from M. Ch. Luzzatto’s poetry to the “Hashiloach” and the “Hador.” I became an admirer of the style and articles of Achad Haam, who became my guide and pathfinder in my confusion – the perplexity of a modern Jew.

My father, regarding me as a hopeless case, stopped interfering with my vocation. Considering that I learned everything possible from Rabinovitz, I left Libau in the spring of 1901 for Berlin to continue my musical education.

Hebrew version:

He kept his promise and during this time taught me music theory and also the beginning of harmony. He also influenced me to become acquainted with the classical music of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart and Mendelssohn, Schubert and others. He acquainted me with Sulzer, Lewandowski and especially Weintraub who had been his teacher, and the rest of the chazzanim who composed music for the synagogue. He taught me how to appreciate good music and the value of Hebrew music.

Berlin spring, 1901

English version:

The day I arrived in Berlin I was accepted in the Stern’sches Conservatorium in the opera-class of Seidemann.[8] The Director of the institution was Gustav Hollaender [1855-1915], a converted Jew who developed in me Germanistic, chauvinistic ideas. His brother, Victor H.[ollander], who was also present, engaged me in the choir of the Charlottenburg Synagogue, of which he was the leader.

My first participation in the opera, however, ended badly; disgusted with the immoral conduct of the players. I gave up my studies and, influenced by Tolstoy’s ideas, I became a follower of them. I abandoned music, the Conservatorium and modern luxury and decided to become a farmer in Palestine. For this purpose I visited S.[imon] Bernfeld [1860-1940], who laughed at my fantasies and told me of the struggle of the poor colonists in Palestine.[9] On the other hand, R.[euben] Brainin [1862-1939] treated me differently;[10] he wrote to a Baron Manteufel in Greece, who maintained a farm school, to accept me. Unfortunately, his reply came too late. The whole summer I lived as a Tolstoian, until my meagre resources were at an end.

At that time there came to Berlin Cantor Boruch Schor [Barukh Schorr, 1823-1904], who looked for singers. My colleagues who accepted Schor’s invitation, induced me to do likewise in order to earn something. Schor was already old and had no voice at all; nevertheless his Jewish admirers clung to him enthusiastically. The compositions he gave us to sing were of very mediocre musical value, although some expressed the Jewish sentiment.[11]

Hebrew version:

In the spring of 5661 (1901), I departed Libau and went to Berlin where I entered the Stern Conservatory and was enrolled as a student in the Opera Department.

However, the life of the theatrical stage quickly disgusted me, which is the reason that after participating in the drama, Don Giovanni, […]

Ausburg, High Holidays 1901

English version:

Soon the High-Holiday season arrived and I was confronted with the question of my existence. My friends recommended me to Frommermann, who maintained a school for cantors. He gave me a place in a Bavarian community. Brainin approved my action in becoming untrue to Tolstoianism.

My preparation in a Weintraub-Sulzer-Lewandowski repertoire was of no avail; there, in Augsburg, I had to learn the South-German chazanuth, which is German, consisting of German melodies of the 17th and 18th centuries. On my way to Berlin I learned from Emanuel Kirschner, hazzan in Munich, that in Leipzig a hazzan was sought. I stopped there and was accepted; one of the Board was a disciple of Weintraub in Koenigsberg. There I could sing real Chazonus.

Leipzig 1901-2

English version:

An old dream of mine was to study in the Leipzig Conservatorium, which I could now realize. I went to Prof. [Salomon] Jadassohn [1831-1902], a sincere Jew, born in Breslau from pious parentage. He was very friendly to me until his death in 1902.

While in Leipzig I studied harmony with Jadassohn, counterpoint with S.[tephan] Krehl [1864-1924], composition with H.[einrich] Zӧllner [1854-1941] and history of music with [August Ferdinand Hermann] Kretzschmar [1848-1924], besides voice-training and piano. There I was able to attend the Gewandhaus concerts under A. Nikisch.

I met and married there a daughter of Cantor H.[illel] Schneider. From Schneider I learned the real Jewish sentiment in Chazanuth and melodic line.[12] As a disciple of Achad Haam I detested the constant chase after Germanism, which I continuously heard in the synagogue song; even Lewandowski seemed Germanized. The life of the Jews in Germany, too, was Germanized. This was not only true of the Liberals, but also of the Orthodox.

Hebrew version:

I decided to leave the school and went to Leipzig where I enrolled in the Royal Conservatory founded by Mendelssohn and studied harmony under Prof. Shlomo Jadassohn who was close to me until his death; studying counterpoint under Stephan Krehl, and composition under Heinrich Zöllner and the history of music under Hermann Kretzschmar. In Leipzig, I acquired a decent knowledge and education in classical music. Prof. Zöllner instilled in me the interest in the study of Hebrew music.

On the other side, my father-in-law, Hillel Schneider, the hazzan in Leipzig influenced me with the understanding and feeling of the Hebrew music to the point that I decided to dedicate myself to its study. Then, I had been a long-time student of Achad Haʿam and I would devour his articles. Thus immersed in his ideas, I would become sad about the Exile of the Hebrew Soul, the synagogal music which had been so permeated by foreign melody; by the fact that all of the works of the great composers of synagogal music were none other than German ones or imitations of them.

Yiska’s memoire:

[1] Grandpa Hillel was the cantor of the Great Synagogue in Leipzig [sic!]. He held this position for 60 years. When he retired they gave him a great send off party. He had a magnificent voice and he was very very observant, as well as liberal meaning generous.

One Pesach in his apartment in Leipzig he was all dressed in white, like they dressed you when you died with your head on a white cushion. He stood there hiding half a matzoh behind his back. Dena, who was good at snatching things, snatched it without him noticing. She was given a little prize. He gave us a guitar when we left for Palestine.

My father Avram Zvi Idelsohn went to him for cantorial lessons when he was 17 and Hillel chose him as a husband for his daughter Zilla, my mother. My grandfather's love for my father was unbelievable. He loved him like a father loves his son.

Regensburg, 1903-4

English version:

At that time, the South-German Chamnuth was considered genuine Jewish. I, therefore, took a position in a Bavarian community, Regensburg, as Chazan and Schochet […]

Hebrew version:

At that time, thirty years ago and more, it was said that the basis of traditional music of the synagogue was located in Southern Germany, so I decided to go to the south of Germany and accepted a position as a chazan in Regensberg where I stayed for two years. There I was compelled to study thoroughly the Ashkenazic chazzanut, and I transcribed it in musical notation. However, very quickly I became aware that it also was very heavily influenced by the German music of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

South Africa 1905-6

English version:

[…] but after two years I received a call from my relatives to come to Johannesburg, Africa, to become a chazan there, which I accepted. I hoped to be able to live there a genuine Jewish life and to sing the Jewish song, but I soon realized my disappointment. About that time the idea dawned upon me to devote my strength to the research of the Jewish song. This idea ruled my life to such extent, that I could find no rest.

Hebrew version:

At this time, family members requested that I come to South Africa for a year and accept a position as chazan. I acquiesced to their pleadings and went to South Africa for a year. However, my intentions to study Hebrew music did not leave me in peace. I was still of the opinion that I must go to Jerusalem and there, only there was the cradle of the original Hebrew music.

Yiska’s memoire:

[4a] His sister Rala was the first to come to South Africa and she wrote to say that there was a position as cantor at Fordsburg synagogue. He had a job which he hated as Chazan and shochet in Germany so he came over with Shoshana, and Zilla who was already pregnant with Eliyahu. They only stayed in SA one year. This was the time everyone thought he would become a Christian because the only piano was in a priest's house in Fordsburg. It was the last thing on his mind. He was not a pianist but it helped him compose. He was a great Zionist and eventually boarded a ship to Palestine. On deck he met Theodor Herzl's secretary who told him he was doing the right thing.

Hebrew Teachers Seminar circa 1906. A.Z. Idelsohn is sitting on the far left, third row from the bottom (MUS 0004 K 04_1).

Jerusalem 1907

English version:

I therefore gave up my position and traveled to Jerusalem, without knowing what was in store for me. In Jerusalem, I found about 300 synagogues and some young men eager to study Chazanuth. The various synagogues were conducted according to the customs of the respective countries, and their traditional song varied greatly from one another. I started collecting their traditional songs. In the course of time the Phonogramm-Archives of Vienna and of Berlin came to my help. After a considerable time the Institution in Vienna invited me to come and present the results of my studies.

As results of my collection and studies the following convictions became crystallized:

1) The Jewish song is an amalgamation of non-Jewish and Jewish elements, and despite the former, the Jewish elements are found in all traditions, and only these are of interest to the scholars.

2) Jewish song is a folk-art, created by the people. It has no art-song, and no individual composers.

3) Composers of Jewish origin have in their creations nothing of the Jewish spirit; they are renegades or assimilants, and detest all Jewish cultural values.

4) The few composers who remained within the fold have mostly corrupted the Jewish tradition with their attempts to modernize it, and have added very little toward genuine Jewish song.

Hebrew version:

In the year 5667 (1907), I left Africa and travelled to Jerusalem. There I found three-hundred synagogues that belonged to all of the tribes of Israel, a microcosm of the ingathering of the exiles. Each community would guard its traditions especially jealously! To earn a living, I accepted a position as a music teacher and a chazan in synagogues of “HaʿEzra” founded by German Jews. I also had private students and among them were Shlomo Zalman Rivlin and Israel Bardaky and Moshe Nathanson, who is now a chazan in New York. I worked in Jerusalem for fifteen years. First, I collected all of the synagogue music from each of the exisitng ethnic groups, for instance, the Yemenites, Babylonians, Persians, Aleppoites, Daghestanis, Bukharans, Sefardim, Moroccans, and the various Ashkenazim, and also the Hasidim. To get a full concept of the Oriental music, I collected the music of the Arabs, the Turks and the Persians.

Yiska’s memoire:

[3e] He could write musical notes like the letters of the alphabet. From little synagogue to little synagogue he passed across Israel, most often on foot on the Sabbath. Once the sun had set and he was permitted to write, he took out his pencil and recorded close to 5000 folk songs and cantorial melodies. These were published in 10 volumes known as the Thesaurus, of which only a few imprints were made. One is now in Hebrew University of Jerusalem and rabbis need to study it to pass their examinations.

[4b] In Jerusalem he taught theory and composition in a seminary which was just a room.

His father Azriel who was a Chasid and who could chant beautifully had instilled a great love of Jewish music in him and in the old city of Jerusalem there were 300 different 'rooms' where people worshipped. He went from one to the next rescuing the old melodies. Almost 5000.

Damascus 1909?

English version:

See his report in Idelsohn, The Jewish Community of Damascus, 1910

Photograph from 1911. Sitting, from left: Idelsohn's sister Feige; mother Devorah; younger brother Yosef Shmuel; father Azriel Fischel. Standing, from left: Idelsohn's sister Esther; brother Yirmiyahu; brother-in-law Itzhak; sister Rivka; A.Z. Idelsohn; and sister Rachel (MUS 0004 K 04_1).

Makhon Shirat Israel 1910-11

Hebrew version:

In 5670 (1910/11), I founded the Makhon Shirat Israel (Song of Israel Institute). I intended to create from all of the different traditions of all of the ethnic groups a unified version and to teach music and chazanuth to the Jerusalem yeshiva students. In this undertaking, I was assisted by my student S. Z. Rivlin z'l, of blessed memory. [Rivlin died in 1962!] However, this attempt was unsuccessful. Also the zealots of Jerusalem blocked my way and would persecute the yeshivah students and threatened them with a herem (ban) and managed to deprive some of them of their halukah.[13]

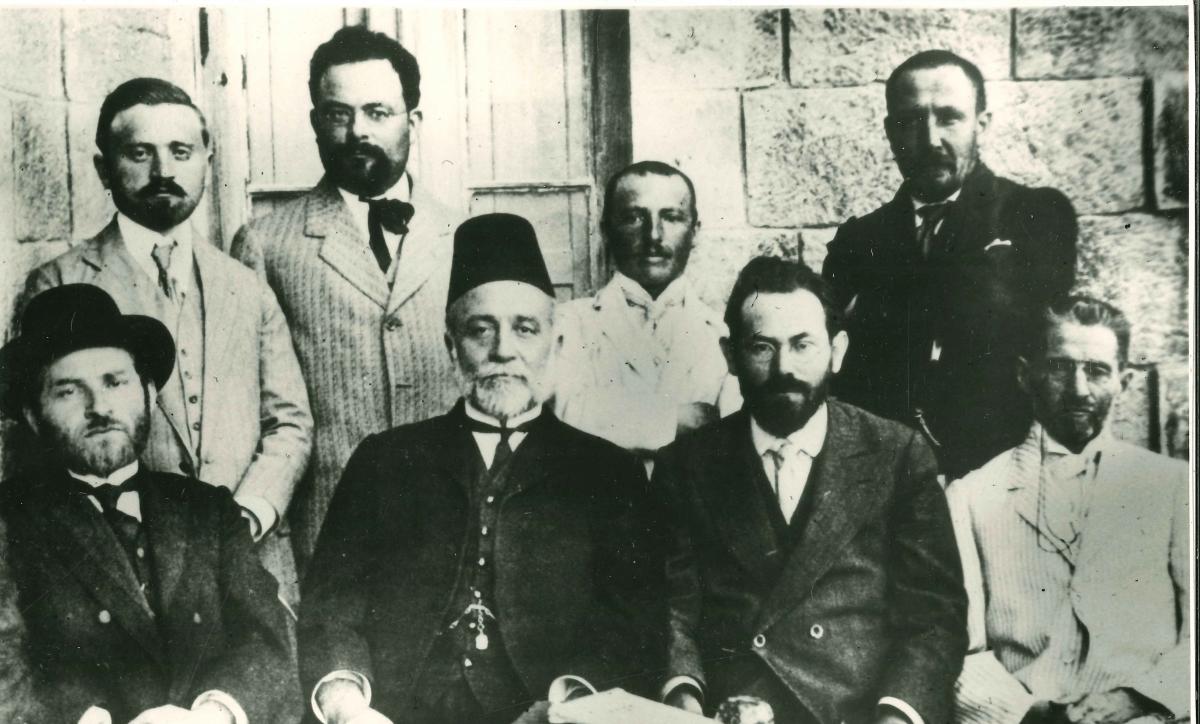

First Hebrew Language Council, Jerusalem 1912. Sitting, from left: Eliezer Meir Lipschütz; David Yellin; Joseph Klausner; Avraham Ben Yehuda. Standing, from left: Yakov Braver; A.Z. Idelsohn; Kadish Yehuda Silman; Chaim Aryeh Zuta (MUS 0004 K 06_1).

Vienna, Berlin fall/winter 1913/4, in Berlin on Dec. 30, 1913 (cf. Loeffler, Hermann Cohen) and publication of vol. 1 of the Thesaurus

English version:

I agreed to go to Vienna, where I was given two rooms by Prof. Exner to work out my records. I applied also for a subsidy from the Academy for the publication of my collection, which I called “Thesaurus of Hebrew Melodies” and prepared six volumes. For this purpose I had to visit the well-known anti-Semite, Prof. Warabazeck, who received me cordially, and due to his influence, the Academy granted me a subsidy for my work. On the other hand the relation of the Vienna Chazanim was very unfriendly, almost hostile.

At the same time there took place the Zionist Congress in Vienna, and I met there Ch. N. Bialik, who induced me to write some Hebrew essays for his magazine “R’shumoth” which he intended to bring out, a request which I fulfilled. The men friendly to me were: Dr. M. Guedemann [Moritz Güdemann, 19 February 1835 – 5 August 1918), Dr. M. Grunewald, Dr. Feuchtwanger [David Feuchtwanger (1864-1936), chief rabbi in the years 1933–1936] – all Rabbis; also Dr. A. Kaminka and A. Stern (President of the Jewish Community). Very friendly was Prof. G. Adler of the University, who invited me to attend his classes in Gregorian chant and to deliver some lectures. My work of the recorded songs and pronunciations I finished and submitted to Prof. Exner. It was published in the Academy Proceedings No. 175.

At that time a fight between the Hebraists and the “Hilfsverein” schools in Palestine was going on. I, though an employee of the “Hilfsverein,” decided for the Hebraists, although double salary was promised my wife by Eph. Cohen. After eight months stay in Vienna I returned to Jerusalem and started my work in the Hebrew schools.[14] From my “Thesaurus” only the first volume could be printed, for soon the world-war broke out and all cultural activities had to stop. I was enlisted in the Turkish army, first as clerk in the hospital, later as band-master in the trenches at Ghaza, from which I emerged after the armistice.

Hebrew version:

So that the transcriptions would be as accurate as possible, the Academy of the Sciences in Vienna came to my aid and sent me a recording machine to record the melodies, and the German Academy also sent me such a machine. Using those tools, I made more than five hundred recordings. Then I was invited by the Academy in Vienna to come and prepare the recordings and set down the results of my research in a book. In the winter of 5673-5674 (1913-1914) I travelled to Vienna and worked at the Physiological Institute under Prof. Exner and wrote up the results of my research in book form. The Academy printed the book with its publisher as Volume 175, part IV in 1917.

The material of the traditional music, I arranged according to the Tribes of Israel and I endeavored to find the common foundations of the Hebrew Music of all of the communities. My opinion was that if there is authenticity in the Music of Israel, then there should be common foundations for all of the communities. And if common foundations like these exist for all of the communities, these are the sparks of the National Soul –– the original Hebrew Music. All of the material that I had assembled, both the musical and the folkloristic material, I set down in one composition that I called the Thesaurus of Hebrew Melodies, in ten volumes. The introductions to volumes I wrote in Hebrew and in German. In Hebrew I wrote a lot more about the folklore, while in German, I provided more research on the melodies. The German introductions, I later translated into English. All of the volumes with the German introductions were printed; the first five volumes with Hebrew introductions were printed; and the first two volumes with the English introductions and the last five were printed. Volumes III to V have not yet been printed in English due to the malevolent government in Germany. This work branched out in other works: Toldot Ha-negginah Ha-‘ivrit (The History of Hebrew Music), in four parts, of which only the first one has been printed by Dvir; a 600 page English summary of this, in one volume, I wrote and it was printed here five years ago; Shire Teman, an anthology of Yemenite poetry that I collected and annotated and the history of their poets, was published by our College four years ago; “Hebrew Pronunciation,” a collection of all of the prevalent pronunciations according to tradition among the Jews, was printed by the German journal Monatschrift in Breslau and also was printed as a special article in Hebrew in the journal, HaShiloah; The History of Prayer that I wrote was printed in English here, three years ago.

During my stay in Vienna, I was invited by Prof. Guido Adler to lecture at the University where I also attended his lessons on the theory of Catholic Music, and it was his suggestion, that I write a book on the relationship between Hebrew and Catholic music which I fulfilled only partially in a few articles.

Yiska’s memoire:

He once travelled to Vienna made discs out of wax with choir and just men singing.[15]

In Jerusalem he used to tell Yemenites and Sephardim and Samaritans to come off the street into our home to record their songs. He had been given an instrument with which to record. They often said no, it was the devil, we are not permitted to do so, but then he'd offer them money, our family's money for meals, we would often forego a meal for these.

Military service in World War I

English version:

I was enlisted in the Turkish army, first as clerk in the hospital, later as band-master in the trenches at Ghaza, from which I emerged after the armistice.

In 1919 I returned to my teaching and research work. The Zionist Commission freed me partly from my work as teacher and I devoted this time for work on the “Thesaurus,” to write the Hebrew introductions, the first of which became very bulky, and I had to separate from it the Yemenite Poetry, which was later published separately under the title “Shire Teman.”

Hebrew version:

During the War, I was drafted into the Turkish Army, and was for a while the conductor of the military orchestra at the front.

British Palestine, 1918-1920

Hebrew version:

In 5679 (1918/1919) with the assistance of the British Governor, General Storrs,[16] I founded an international music school.

I also founded a large Hebrew choir in Jerusalem and organized concerts for a number of years. My work as a music teacher resulted in my writing a pedagogical book for teaching music, in Hebrew; a songbook for schools, kindergartens and home in two parts called Sefer shirim and also for choirs.

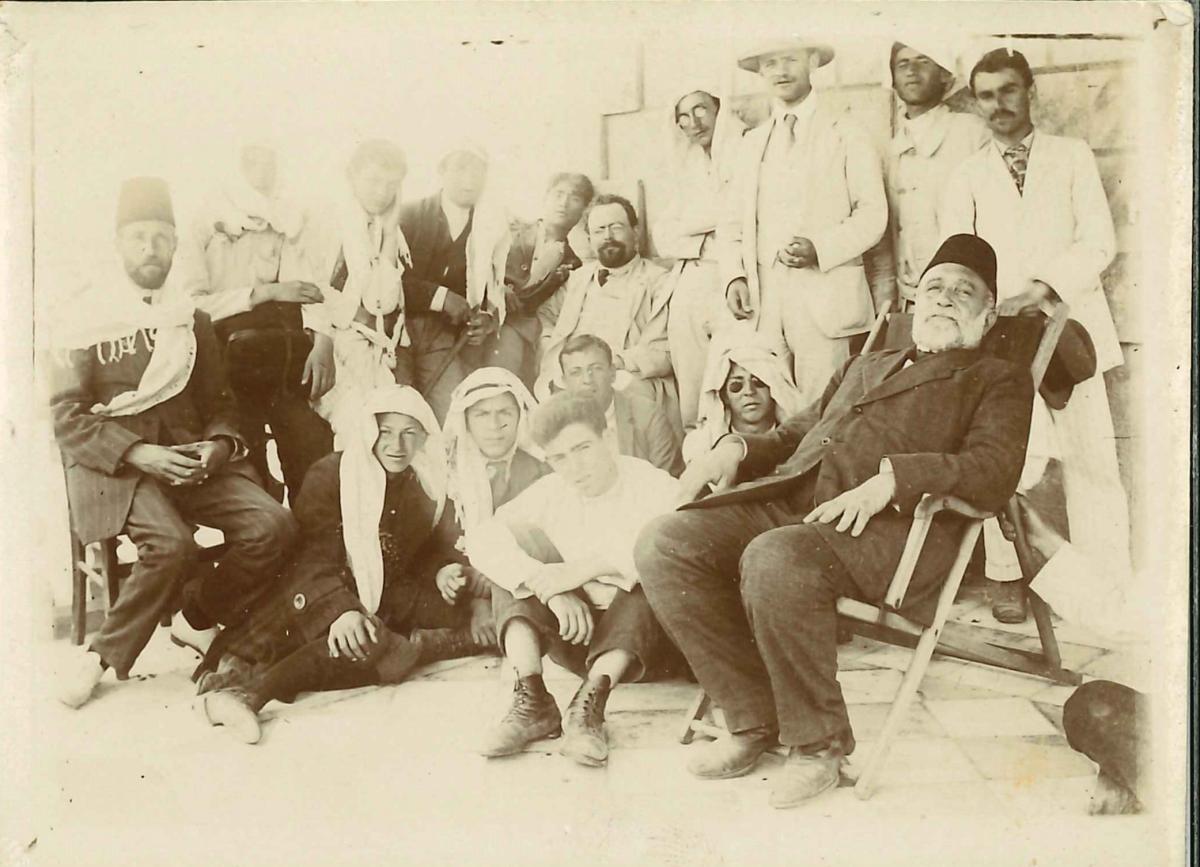

Idelsohn is sitting in the center of the photograph, back row, with David Yellin seated in a chair in the right foreground. It is likely that some of the others in this photograph were among Idelsohn's musical informants in Jerusalem. (MUS 0004 K 07_1).

Germany, England 1920-22

English version:

In 1921 I decided to go to Europe to publish my works. I took my family with me. I arrived for the Zionist Congress in Carlsbad, where Dr. V. Jacobsohn, then head of the “Juedischer Verlag,” bought my manuscripts of “Sepher Hashirim,” and Bialik encouraged me to write a history of Jewish music, the first volume of which he published in the “D’vir,” the other four volumes remained in Ms. up to date. Upon sending the second volume, Bialik wrote me... “your first volume is still lying in our store, only a few copies are sold...we have no courage to print the second one.”

In Carlsbad I met also the head of the K’lal-Verlag in Berlin, who published my “Z’lile Haaretz” and “Z’lile Aviv”; there I met also B. Cahan (the owner of “Yalkut”) who brought out my “Sepher Hashirim” 1 and “Shire T’filloh”, 2nd edition. In Berlin I met Benjamin Harz with whom I arranged to publish my “Thesaurus” in Hebrew, German and English, and by the end of 1922 four volumes came out. During the year that I was in Berlin, I materialized an old dream, I found a publisher to put out my JEFTAH, of which I wrote both the words and music and which was the first Hebrew opera ever written. Negotiations with the Oxford Press and other publishing companies were unsuccessful. After more than a year’s stay in Berlin my friends advised me to go to America on a lecture tour, which I did. Before that I had lectured already in Vienna, Berlin, Breslau, Posen, Leipzig, London, Oxford, Amsterdam and in other places.

Hebrew version:

At the end of 5681 (late summer of 1920) I travelled to Germany to publish my books. There, two different publishers were found for me, especially, the late Bialik who published the first volume of my History of Hebrew Music; and Binyamin Hartz, who was then in Berlin a publisher and book seller of means, and took upon himself to publish my Thesaurus and indeed published the first five volumes in Hebrew and in German.

Yiska’s memoire:

[5] He then left the family in Jerusalem and travelled to Germany to pursue his work. In 1921 the family received a letter from Avram Zvi that they would be moving to Germany.

[6] At first in Germany Ima found a tiny room in the poorest suburb which was teeming with prostitutes and children. There was an oven to heat the room, a table, two primus stoves and an alcove for coal. There was a bed for Ima, a mattress for Dena, and a narrow sofa for me, which stood under a warped window. On snowy and rainy nights I got drenched and froze and it wasn't long before Ima became ill and Dena developed asthma. I looked after both of them which included doing all the shopping. Then AZ left on a lecturing tour and when our grandpa Hillel visited us there he demanded we move to his apartment which we did.

From there the family moved to Berlin to better rooms. AZ's accompanist, Mr. Dimont found them an apartment but Zilla became very ill and required a serious operation. Yiska was 11 and every day she cooked a stew for her father and for Mr. Dimont. She befriended Mr Dimont's daughters who both were very musical especially the one. They eventually emigrated to Brazil. […] During the time the two families spent in Berlin, father decided to record a number of songs and assembled Mr. Dimont and all their children in the apartment. They recorded 10 records and copies were sent to Shoshanna in Johannesburg. These are now in Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Before long funds ran out and father began a lecture tour in the US, coast to coast. For two years Zilla, Dena and Yiska remained in Germany. At boarding school they had so few garments it was difficult to be untidy and the housemistress was always holding the Idelsohn sisters up as models of neatness.

Ima visited us several times and one time she wrote to inform us that we were to return to Palestine. […] As soon as we arrived in Jerusalem, Ima immediately repaid her debts of three and a half years ago. Everyone said they were always sure Ima would pay them back. She rented a two room apartment and hired a student teacher to help Dena and I meet the required standard for school. This young man paid more attention to me than to Dena who (by Yiska's telling) was the prettier of the two. His attentions were unwelcome. She was only 14. Then to their dismay AZ didn't join them.

Cincinnati 1922-1935

English version:

Upon my arrival in the U.S. [November 15, 1922], I found Dr. and Mrs. De Sola Pool, Prof. M. Kaplan and Dr. Stephen Wise friendly, but my sincerest friends became Prof. and Mrs. Samuel S. Cohen, then in Chicago. It was due to their efforts that I was invited to catalogue the Birnbaum collection in the Hebrew Union College Library in Cincinnati and later was asked to teach at that college. They furthered my cause in various ways.

In 1924 I settled down in Cincinnati as Professor of Hebrew and Liturgy, as well as Jewish Music, but before that I toured the country lecturing, from coast to coast.

During my stay in Cincinnati, I added four more volumes to my “Thesaurus,” making it ten volumes. The President of the College, Dr. Morgenstern, secured funds for the 5th and partly for the 6th volume, but the American Council of Learned Societies decided to grant me a subsidy for all the remaining volumes, and thus I was enabled to publish my “Thesaurus” in ten volumes in German and English, the first five volumes also in Hebrew.

From this work grew out several others: research in the Liturgy, which I published in the “Thesaurus,” Vol. 3 and 4; research into the Poetry, which I published in the “Hator” and “Hashiloach” and separately in book form under the title “Shire Teman”; pronunciation of Hebrew, published in the “Hashiloach” and in the “Monatschrift” 1913, which was put out separately as a reprint; a Manual, published in 1926 by the Hebrew Union College – an Extract of the melodies of my “Thesaurus.” I decided to prepare in English an extract of the four volumes of the History of Jewish music, which I had in Hebrew manuscript and in which Henry Holt, New York, was interested. This appeared in 1929, I wrote also a History of Liturgy which Holt published in 1932. The Brotherhood ordered from me the “Ceremonies of Judaism,” and these were put out in book form in 1929, a second enlarged edition in 1930, and a third edition in 1932.

My activity as teacher of singing and as Chazan gave me ample opportunity to create along these lines. Already in 1908 I published in Jerusalem under my supervision two volumes “Shire Zion” for choir and solo, also a theory of music in Hebrew, “Torath Han’gina” (1910), and “Sepher Hashirim,” vol. 1, likewise several essays in various periodicals, and “Shire T’filla” 1. While in America, considering the situation in which Judaism is placed, I composed and published two Friday-evening services and one Sabbath-morning Service for four part-choir with organ accompaniment, according to the Reform ritual; “Jewish Song-Book,” two editions, the third edition is being delayed due to my illness. I also put out a Friday-evening Service for one voice with accompaniment.

Hebrew version:

After spending more than a year in Germany, my friends advised me to travel to America, a place where I could deliver lectures on the subject of Hebrew Music. I traversed all of America from the east to the west, from north to south delivering lectures [April 7-May 7 lectures in Chicago, June 30, 1923 lectures at CCAR in New Jersey]. Having been in America more than a year [since November 15, 1922], I was invited to Cincinnati to organize the catalogue of a music collection that the [Hebrew Union] College had purchased from the estate of E. Birnbaum of Konigsberg. Afterwards I was invited to be Professor of Hebrew and Hebrew Music and Prayer in this Seminary. I served in this post for ten years. In these years I managed to complete the remaining volumes of my Thesaurus and to print them and also, to collect material for two additional volumes that are still in manuscript form.

During the entire time I worked, I would turn my attention to the synagogue and compose music for some prayers. Among those which were published: Shirei tʼfilla, for hazzan and choir in Berlin, in 5669 (1908-1909) and the second edition in 5682 (1921-1922); two pieces that are called Services in English, for Friday night; ʿAvodah for Shabbat. These pieces are based on versions of the Massorah, for instance, “Magen avot,” “Ahavah rabbah” and similar and they are intended for a choir and magrefa-organ; Sefer shirim – a songbook for the synagogue, school and home, accompanied by the magrefa or piano, the first edition in 1928 and the second edition in 1929 and now the third edition is about to be released; ʿAvodah for Friday night for a single voice and magrefa, according to the Reform and Orthodox versions.

A dream of my youth was to create a Hebrew opera based on the Hebrew music and historical Jewish text. For this I wrote two plays, one, Yeftah and the second one, the Prophet Eliyahu. I also composed the music for Yeftah which was printed in Berlin in 5682 (1921-1922). When I reached my fiftieth birthday [1932], our College celebrated the occasion and granted me the title of Doctor for my work in the field of Jewish Studies and Culture and for my endeavors to endow beauty to Worship of God.

Yiska’s memoire:

He wrote that he had been offered a chair as Professor of Hebrew Liturgy and Jewish music at the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati and for them to join him asap. Once again the two girls and their mother had to leave their beloved homeland. With heavy hearts they sold their few pieces of furniture and set sail in another cargo ship across the ocean. […]

After this difficult journey there was an unexpected surprise waiting for them in Cincinnati. They were welcomed by Mr. and Mrs. Cohen with whom AZ had been staying in a beautiful double storied house. Mrs. Cohen taught Yiska and Dena English and general knowledge for three months. Dena’s general knowledge was good, Yiska's was nil. At the beginning or the year they were enrolled in the same class at school. […]

Then Ima fell ill and needed another serious operation. The surgeon in Chicago warned the family that her chances of surviving it were not good but Zilla came back to the joy of her family. Ima although never formally educated was an avid reader of philosophy and she had a lovely soprano singing voice. Around this time she had some singing lessons and even helped AZ improve his techniques.

In 1927 AZ sent Ima and Dena back to SA and Yiska who was 16 remained with her father to keep house. The separation was a privation Yiska could hardly bear. Here as an aside Yiska tells me that all the other professors wives were educated and that he was no longer proud of his wife.

Idelsohn at Hebrew Union College, sitting on the bottom row, fifth from the right (MUS 0004 K 08_1).

Disease and decay 1931-1937

English version:

In 1929 I was taken sick with coronary-vessel disease, and was laid up for six months. But in 1931 I had a paralytic stroke on my left side. This repeated several times, so that I could not teach any more, nor write, nor move about, nor read much. The Board of the College granted me a pension, for the rest of my life. I can do nothing, but waste my time in reflection.

Hebrew version:

At the same time, one day while I was sitting in the classroom and teaching lessons, suddenly the left side of my body was paralyzed. After being on my deathbed for a long time, things improved for me a little bit and I returned to work. However, about a year later, suddenly my speech was taken from me, although after a while the power of speech returned, but only off and on. Also my right hand was affected and I could no longer write. The doctors prohibited me from doing any kind of work and the Directors of the College granted me a pension for the rest of my life.

Although I try to keep a little busy, I am unable to create now and so I continue my life of idleness as a punishment from Heaven.

“Here, in short are the events of my life, few and evil.”[17]

Yiska’s memoire:

[…] Then Ima received a letter from father, he was ill and wanted Ima to return to America. Can you believe it? Ima was the most forgiving loyal wife. Before they had met Ima, the Cohens once asked father what is your wife like. He replied that she is a pure soul. Very reluctantly Ima left her daughters and her grandchildren and joined father. […]

My parents moved to Miami Florida […]. On three occasions I went to Florida to visit father who was becoming more and more paralyzed and whose movement had become restricted to one little finger. One time Ima found him with a tie around his neck. In this greatly reduced state he was extremely restless and frustrated and indicated that he wished to return to SA to be with his family.

In New York rabbis, cantors, professors all called on father in the hotel. He couldn't reply but I interpreted what he meant by the movements of his one moveable finger. I remember the stewards were on strike on the ship and the twenty-one-day voyage was a nightmare.

Johannesburg 1938

Yiska’s memoire:

We were met in Johannesburg by notable people and family. The first thing I said to my sisters was take over. I was exhausted both mentally and physically. […]

Ima and I moved into flat in Yeoville and in every flat we lived in from there on I had my beauty salon. On July 1, 1938 it was father's 56th birthday. Ima baked him a great big cake with lots of candles and 57 iced on top. A shiver ran through our bodies as he exerted great effort and with his with only moveable finger removed the top of the iced numeral 7. Six weeks later he died.

Whilst lighting a yortziet candle to commemorate his father’s passing Eliyahu had a heart attack and died.

Endnotes

[1] Liepaja in western Latvia, the third largest city of that country. Until 1914 it was one of the most important Baltic ports of the Russian Empire and a favorite summer resort. It was under heavy German/Prussian cultural and political influence.

[2] Zamet or Samogitia is an area in Lithuania adjacent to Courtland. Courtland Jews defined themselves against the “zameter”, i.e. the “other” Ashkenazi Jews. See Jacobs, Neil G. Yiddish: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010, p. 61.

[3] By “intelligent” Idelsohn may have had in mind “modern” or “useful.”

[4] Jūrkalne in Latvia.

[5] Sing. heder, traditional elementary religious school for boys.

[6] Today Žemaitija, province in north-west Lithuania, not far from Idelsohn’s family home in Libau/Liepaja.

[7] This sour memory of Birnbaum contrasts with the laudatory terms with which Idelsohn praised his predecessor in his essay Song and Singers of the Synagogue.

[8] Julius Stern (from whom the institution eventually took its name), Theodor Kullak and Adolf Bernhard Marx founded the Stern Conservatory in 1850 as the Berliner Musikschule. In spite of its openness, the school was always considered to be a “Jewish” hub. The Conservatory eventually was absorbed into larger institutions of music high learning in Berlin.

[9] Dr. Simon Bernfeld was a distinguished independent scholar born in Galicia and educated in Lemberg, who settled in Berlin from 1898 becoming a major figure in the Jewish Studies’ circles in the city.

[10] Reuben Brainin was a writer, publicist, translator and biographer. He was active in the Zionist movement from its beginnings. Eventually settled in the USA where he died.

[11] Cantor Barukh Schorr was one of the most renowned names of the older 19th century generation of cantors (of Hassidic background) from Galicia. In spite of his harsh criticism, young Idelsohn’s exposure to this experience must have left in him an indelible memory.

[12] Schneider born in the village of Sidra, north-eastern Poland, in 1860 was cantor of the Brodyer Synagoge (Talmud-Thora-Synagoge) in the Keilstraße since 1898. See Kowalzik, Barbara. Jüdisches Erwerbsleben in Der Inneren Nordvorstadt Leipzigs 1900-1933. Leipzig: Leipziger Univ.-Verl, 1999, p. 29. He died exiled in Oslo in 1941. Pianist and pedagogue Sina Berlinsky, whose family was a member of this synagogue remembers: „Unvergessen ist ihr die „schöne, warme Bariton-Stimme“ (STS BerlinskiS) von Hillel Schneider, dem Kantor bzw. Oberkantor dieses Gotteshauses, der 1939 ins Exil nach Oslo ging und 1941 dort starb (HeldS 1995, S. 57)“ On the syangogues of Leipzig, See also: http://www.thomas-chinkoeth.de/SCHUBLADEN/LEIPZIG/MusikAnLeipzigerSynagogen.pdf

[13] Halukah (lit. distribution): funds donated by Jewish communities worldwide in support of the Jews and Jewish learning in Eretz Israel/Palestine.

[14] He was there in August 1913, so returned to Jerusalem in March 1914. Important: He does not mention the trip to Berlin where he met Hermann Cohen and attended the 11th Zionist Congress in Vienna. Check he is mentioned in: Stenographisches Protokoll der Verhandlungen des XI. Zionisten-Kongresses in Wien vom 2. bis 9. September 1913 / herausgegeben vom Zionistischen Aktionskomitee. Berlin, 1914

[15] Is she confusing the trip to Vienna (1913) and Berlin (1922) when he indeed recorded with men’s choir?

[16] Sir Ronald Storrs served in the rank of Colonel as Military Governor of Jerusalem from December 28, 1917 to June 30, 1920 and as Governor of Jerusalem and Judea from July 1, 1920 to November 30, 1926.

[17] A paraphrase of Jacob's summary of his life (Genesis 47:9) “… few and evil have the days of my life been…” in Yuval Studies V, The Abraham Zvi Idelsohn Memorial Volume, Chap. I, Introduction to Idelsohn's Autobiographical Sketches, p. 17.