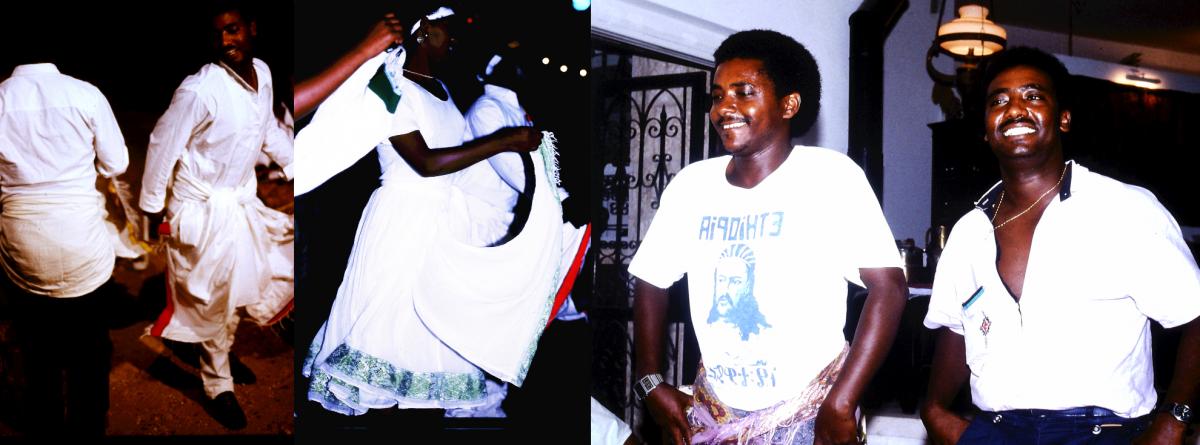

I spent the summer of 1989 living in a Nazareth Illit (today Nof HaGalil) neighborhood largely populated by new immigrants from Ethiopia, and working as a volunteer in Meseret, a center that supported traditional Jewish-Ethiopian crafts (weaving, pottery, basketry) and music. The neighborhood had grown around an absorption center (merkaz klita), where new Jewish immigrants are housed, taught Hebrew, supported in their first steps in the host society and also, inculcated with hegemonic values of Israeli citizenship. Meseret (“Tradition”), the brainchild of Gadi Negusse—who arrived with his family during Operation Moses of 1984-5, when over 6,000 Ethiopian Jews (Beta Israel) were airlifted from refugee camps in Sudan—was housed in a nearby abandoned kindergarten. The center became home to older men who spun cloth on traditional weaving looms; women who spun thread unto bobbins or brought homemade baskets and pottery to be fired at the kiln and put up for sale, and a traditional music and dance troupe. Also named Meseret, the troupe played in local community events in a variety of lineups, and with a full lineup and traditionally-clad dancers in high-exposure general-public events, such as the Safed Music Festival and the Red Sea Jazz festival. The kindergarten’s yard sported a traditional oven for baking injera (Ethiopian flatbread); later a tukul, a traditional Ethiopian hut, was built on the premises, to be used for community events and as a means of introducing tourists to Ethiopian culture. Traditional Ethiopian musical instruments including the krar (harp), masinqo (one stringed fiddle), washint (flute) and kebero (barrel drums) were prominently displayed at the center.

Ethiopian Jews in Israel - a Musical Ethnography

I was then an undergraduate student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, double majoring in anthropology and music. Ethnomusicology was not yet available as a field of specialization for an undergraduate, but the university was supportive of my wish to conduct independent research among the Beta Israel community in Israel. In 1989, when I arrived in “the field,” over 20,000 Beta Israel had immigrated to Israel, which was becoming a new center of life for the Ethiopian Jewish community. The oftentimes harrowing stories of their journeys, the dramatic airlifts from Sudan, and the romantic allure of narratives of origin and return that framed them as “lost brothers” (or tribes) now reuniting with the Jewish collectivity in its contemporary national reincarnation, sparked both media interest and the popular imagination.

But the community underwent (and still does) a hard landing in Israel. In 1989 most of the immigrants had remaining family and friends in Ethiopia unable to make the journey. Many had also lost family members en-route in the desert between their points of origin in Northern Ethiopia and Sudan, or in the overcrowded, underserviced Sudanese refugee camps (approximately 4000, see Kaplan and Rosen 1994). Detachment and loss were cause for much anxiety, longing, and trauma for the immigrants. Many found it difficult to integrate into the Israeli economy and society, due to language barriers, skills that were more fitted to rural Ethiopia than to the urban Israeli economy, the paternalistic attitude of the absorption bureaucracy, and the racism they encountered among the host society. Finally, while in Ethiopia Beta Israel were marginalized and oftentimes persecuted as Jews, in Israel their Jewishness came under the scrutiny of the Orthodox Chief Rabbinate. Initially the Rabbinate required rituals of pro forma “conversions” from the immigrants and, importantly, it disempowered the spiritual leadership of the community (the priests—qessotch in Amharic, qessim in the Hebrew adaptation), in effect dismantling the qessim’s authority.

Questions about the origins, history and (pre-halakhic) Judaism of Beta Israel had also captured the imagination of scholars (see for example Kaplan, 1993; Parfitt and Trevisan 2013; Salamon 1999). As an academic discipline, ethnomusicology was at the forefront of this interest. Kay Kaufman Shelemay’s groundbreaking Music, Ritual and Falasha History (1986) situated Falasha liturgy and religious practices in a broader Ethiopian and Christian context rather than strictly a Jewish one. In Israel, a French-Israeli collaboration headed by ethnomusicologist Simha Arom located several qessim and began to record Beta-Israel liturgical music. By 1989 this effort had become a collaboration of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and the Langues et Civilisations à Tradition Orale (LACITO), with the ambitious aim of recording the entire Beta-Israel liturgical calendar and analyzing it. This was perceived as a salvage project that would preserve a tradition headed to extinction, as liturgy and ritual were being replaced with what was understood in Israel to be “normative” Jewish practices (Tourny 2002; see also Atar 2005; Tourny 2009; Tourny and Arom 1999; Arom, Alvarez-Pereyre, Ben Dor and Tourny 2019).

My interests lay elsewhere; my focus was on secular music traditions, as I believed these would reflect the joys, hardships, and daily life of a community in transition/crisis—which I framed in the (quite anachronistic and in hindsight, somewhat crude) disciplinary lexicon of the times as a study of “the dynamics of assimilation and cultural continuity” (p.1). Yet this angle brought a fresh perspective to contemporaneous scholarship, much of which was focused on the Jewish aspects of the community’s culture, or alternatively, had sought to achieve public policy goals by finding ways to facilitate the assimilation of Ethiopian Jews into hegemonic Jewish Israeliness. Studying secular musical traditions that Beta Israel had shared with their neighbors in Ethiopia meant not discounting the relevance of their “Ethiopianness” to the Israeli environment and acknowledging the complexities of meaning-making and cultural identity among immigrants labeled “falashas” (foreigners) in Ethiopia, now encountering new frames and processes of exclusion and inclusion.

Chapter 1 provides a brief history of Ethiopian Jewry, including scholarly theorizations about the origins of the community; Beta Israel’s own narratives of origin; their evolving relationships with Christian kings and emperors—which over many centuries had brought increasing marginalization, forced conversions, dwindling numbers and cultural prejudices against Ethiopian Jews; the even more precarious situation they encountered following the 1974 Marxist revolution in Ethiopia, and life in Israel. Chapter 2 outlines and critiques the then-available (rather scant) literature in English on traditional Ethiopian music of the Amhara culture area, from which the music and dance of immigrants in Israel was derived. The chapter focuses most especially on the four Ethiopian modes (qignit) covered in this literature, in relation to performance practices I encountered in Israel among musicians who had not enjoyed formal training. Chapter 3 covers the functions of music in daily life in Ethiopia and in Israel, focusing on “change and continuity” largely through performance practice, the relationship between music and dance, and the (traditionally Christian) azmaris—the professional musicians of Ethiopia—whose role and functions in community celebrations were being subsumed by Jewish Ethiopian lay musicians in Israel, for whom playing had previously been more a means of self-expression, rather than of entertaining others. The chapter also explores the reasons for the lack of professional azmaris among the immigrants. Chapter 4 focuses on the musical instruments played by Ethiopian Jews in Israel, to include variations due to available materials, organology, tunings, playing positions, performance practices and (at times divergently interpreted) symbolic value. Chapter 5 discusses song texts, highlighting the centrality of “wax and gold”—a metaphor that stands for the multiple semantic layers that characterize Amhara poeticism—for understanding song texts. The idiom draws on the goldsmith’s method of constructing a clay mold around a form made of wax, after which the wax is removed, and molten gold is poured unto the clay mold. Coded speech and poetry, presented in minimalistic texts (the wax), is both a key to the semantic “gold” and to negotiating life and power structures in society. In the Israeli context, wax and gold also provided a stock of lexical metaphors immigrants applied to post-immigration communal situations and personal mindsets, including sentiments of loss and separation, nostalgia, and hopes for the future (full song texts in Appendix 4). Chapter 6 provides detailed musical analysis of several songs: a solo voice and masinqo performance, a solo voice and krar performance, a solo washint performance—which became an occasion for other attendants to whimsically recreate the sonic environment of a shepherd guarding his flock in Ethiopia—and an ensemble performance of a dance tune (zefen) (full transcriptions available in Appendix 5).

As can be seen in the above outline, my thesis was written in the vein of ethnomusicological projects of the period, privileging certain foci over others. It is more empirically descriptive than interpretive. Musical analysis provides a prominent textual focus (chapter 6 is the longest in the thesis) despite the details admittedly lost in adapting the richness of the improvisational performances I recorded to Western staff notation. The daily interactions I witnessed between the immigrants and veteran Israelis—festival promoters, visitors at the center, etc.—were largely left outside the thesis. A joint performance of Meseret with Israeli rock artist Ehud Banai, the product of a chance encounter at the Safed Music festival that combined his song “Black Brothers” (“Ahim Shchorim”) with a Meseret staple, is glossed over, despite its poignancy in the moment of performance; I believe this is due to the reflexive bent of privileging “the traditional” so common to ethnomusicological work of the period. Gendered issues are not extensively discussed, although they were constantly present in the field, including the ongoing negotiations it took to secure the performances of the young women dancers in the band, vis-à-vis reluctant parents. Finally, there is no engagement with critical theory and the prism it brought to ethnomusicology in the following decade of the 1990s, when such theoretical frameworks led to a heightened awareness of, and commitment to, questions of power, performativity, and the politics of race, class and ethnicity within the discipline.

Later studies of musical life among Ethiopian Jews in Israel highlight the abandonment of the traditional, rural-based musical practices I describe. They also reflect a progressive engagement with social theory and particularly with race and Afro-Diasporic studies for understanding how social processes are intertwined with musical practices. In many ways these go hand in hand; my study was undertaken before Ethiopian superstars Teddy Afro and Aster Aweke were brought to Israel for community celebrations and youth began turning to Bob Marley, Tupac Shakur and Afro-diasporic musics for inspiration and as sites for negotiating their marginalized citizenship in Israel.

Based on fieldwork undertaken circa 1992-1994, Marylin Herman’s Gondar’s Child (2012) follows the ensemble Porachat HaTikva and its negotiations of the concept of honor—developed in Ethiopia as a means of facing discrimination in a Christian environment—and how it is applied in a new environment in which they are marked by skin color and discrepant practices of Judaism; interestingly, the band’s repertoire, based on urban Ethiopian traditions was recast as a tradition-based project. The studies of Malka Shabtay (2001; 2003), David Ratner (2015; 2019) and Gabriella Djerrahian (2018) engage with the listening and consumption practices of Ethiopian-Israeli youth who were either born in Israel or had immigrated when they were young, and who favored reggae and hip-hop over other genres. Shabtay views their identification with these music genres—reggae for its Ethiopian referents and rap because it reflects their own racialized experiences—as a means of identifying with “blackness” as primary identity (alongside a delinquent lifestyle) over marginalized Israeliness. Ratner explains the identification with rap vis-à-vis Paul Gilroy’s (1993) approach to the ‘Black Atlantic’ whereby hip-hop becomes both reflective and constitutive of transnational and politicized black identities, and in the local context, is also favored over other available choices: a folklorized, depoliticized Ethiopianness or alternatively, an inauthentic, unconvincing version of Israeli nativity. For Djerrahian, music for these youth is a means of reinventing their Ethiopianness, and of mobilizing the African and Ethiopian diasporas to stake a claim for respect and empowerment “at the epicenter of a third, Jewish diaspora: Israel” (2018: 162). Finally, Ilana Webster-Kogen’s Citizen Azmari (2018) moves from a focus on the politics of reception among youth to one centered on cultural producers and disseminators. Via several case studies showcasing the different musical styles that Ethiopian-Israelis create and work with—Ethiopianist, Afro-Diasporic, and Zionist-based, separately or in combination—she highlights how musical style is key to understanding practices of citizenship and sociopolitical critique. She interprets style in this context as the “gold” that cannot be fully articulated in speech, among citizens facing racial discrimination and seeking to formulate a variety of (contradictory, overlapping, and divergent) spheres of belonging.

In sum, the studies discussed above provide a window grounded in social theory into the evolving challenges, life circumstances, musics and identities of Ethiopian Jews in Israel across three decades. Compared with these works my thesis remains more descriptive than theoretical in style and substance. Yet it is perhaps the only in-depth study of Ethiopian Jewish music in Israel occurring in the moment of transition, when folkloric styles played by community members were not only a means of commemorating the highlands of Ethiopia, but of negotiating daily life in Israel and the fresh traumas of loss and separation. I am therefore happy it will now be published, along with the newly digitized tracks discussed in the thesis.

Musical Examples

Example#1: "Untitled"—Ya’acov, vocals and masinqo

Example#2: “Kwane kwane”—Daniel, vocals and krar, followed by Meseret ensemble version of Kwane kwane

Example#3: “Come, come”—Daniel, vocals and krar

Example#4: “Shepherd’s tune”—Natan, washint; Meseret, soundscaping

Example#5: “Hailalo”—Meseret: vocals, washint, krar, kebero

Video documentation

Music and dance by Meseret, filmed by Nili Belkind

Meseret at Soweto Club, Tel Aviv; video courtesy of Meseret

References

Arom, Simha, Frank Alvarez-Pereyre, Shoshana Ben-Dor and Olivier Tourny, 2019, The Liturgy of Beta Israel. Music of the Ethiopian Jewish Prayer. 3 CDs Anthology of Music Traditions in Israel 26. Jewish Music Research Centre, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Atar, Ron, 2005, “The Function of Musical Instruments in the Liturgy of the Ethiopian Jews.” The Jews of Ethiopia: the Birth of an Elite. Pafitt, Tudor & Emanuela Trevisan Sami, eds. London: Routledge.

Djerrahian, Gabrielle, 2018, “The ‘End of Diaspora’ is Just the Beginning: Music at the Crossroads of Jewish, African and Ethiopian Diasporas in Israel.” African and Black Diaspora: an International Journal 11(2):161-173.

Gilroy, Paul, 1993, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Herman, Marilyn, 2012, Gondar’s Child: Songs, Honor, and Identity among Ethiopian Jews in Israel. Trenton, NY: Red Sea Press.

Kaplan, Steven, 1993, The Beta Israel (Falasha) in Ethiopia: from Earliest Times to the Twentieth Century. New York and London: New York University Press.

Kaplan, Steve and Chaim Rosen, 1994, “Ethiopian Jews in Israel.” The American Jewish Year Book 94:59-109.

Kaufman Shelemay, Kay, 1986, Music, Ritual and Falasha History. East Lansing, MI: African Studies Center, Michigan State University.

Parfitt, Tudor and Semi E. Trevisan, 2013,The Beta Israel in Ethiopia and Israel: Studies on Ethiopian Jews. London: Routledge.

Ratner, David, 2015, Black Sounds: Black Music and Identity Among Young Israeli Ethiopians. Israel: Resling [Hebrew].

— 2019, “Rap, Racism and Visibility: Black Music as a Mediator of Young Israeli-Ethiopians’ Experience of Being ‘Black’ in a ‘White’ Society.” African and Black Diaspora: an International Journal 12(1):94-108.

Salamon Hagar, 1999, The Hyena People: Ethiopian Jews in Christian Ethiopia. Berkeley and London: University of California Press.

Shabtay, Malka, 2001, Between Reggae and Rap: The Integration Challenge of Ethiopian Youth in Israel. Tel-Aviv: Tcherikover. [Hebrew].

— 2003, “'RaGap': Music and Identity Among Young Ethiopians in Israel.” Critical Arts: South-North Cultural and Media Studies 17(1-2):93-105.

Tourny, Olivier, 2002, “Anthology of the Liturgy of the Ethiopian Jew: A Franco-Israeli Program as Impetus for Research.” C.d.R.F.à. Jérusalem, ed. Pp. 99-104. Jerusalem Centre de Recherche Français à Jérusalem.

— 2009, Le Chant Liturgique Juif Éthiopien: Analyse Musicale d’Une Trdition Orale. Paris: Peeters.

Tourny, Olivier, and Simha Arom, 1999, “The Formal Organisation of the Beta Israel Liturgy—Substance and Performance: Musical Structure.” In The Beta Israel in Ethiopia and Israel: Studies on Ethiopian Jews. T. Parfitt and E. Trevisan Semi, eds. Pp. 252-256. Richmond, Surrey, UK: Curzon.

Webster-Kogen, Ilana, 2018, Citizen Azmari: Making Ethiopian Music in Tel Aviv. Middletown, CT: Wesleyen University Press.