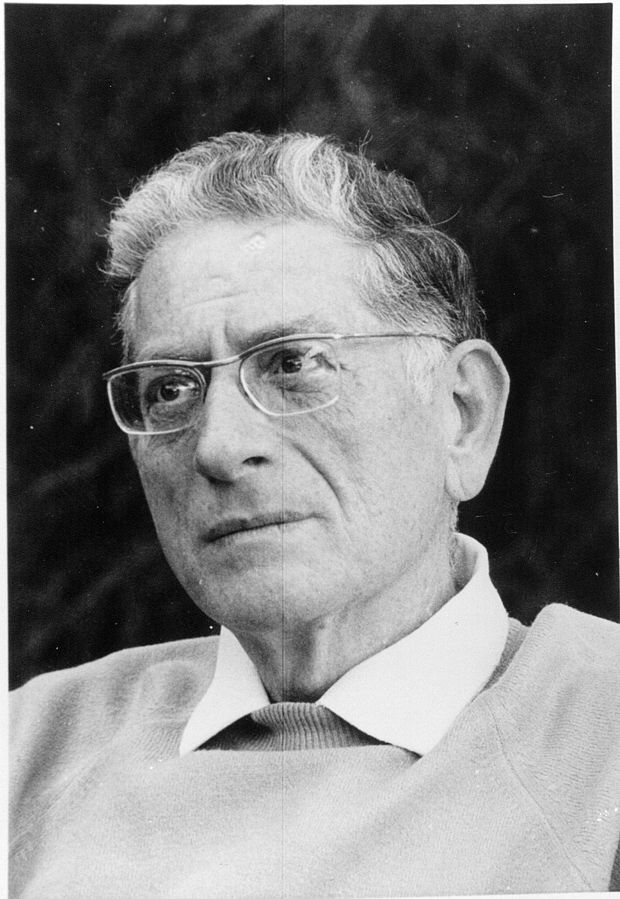

Mordekhai Seter (Novorossyisk, 1916 – Tel-Aviv, 1994, immigrated to Palestine in 1926) received the Israel Prize in 1965 for his Midnight Vigil (Tikkun Hatzot), an oratorio for tenor, three choirs and orchestra depicting the redemption of the Jewish people. This oratorio has been considered since its premiere in 1961 as an Israeli masterpiece. Midnight Vigil, performed in celebratory occasions, was chosen to conclude the first Israeli Music Celebration (September 1998; an annual festival since). It was also selected for the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra’s Millennium Festival program (January 2000, along with Beethoven’s Ninth and Bach’s B minor Mass).

The youngest of the founders’ generation, Seter emigrated from Russia as a 10-year old child, and at 16 he went to further his musical education in Europe (Paris, 1932-1937, studying with Nadia Boulanger and Pnina Salzman). Like his peers of that generation, he acquired his formative musical education in Europe, and had already become influential in Eretz-Israel by the 1940's. Unlike the other Founding Fathers of Israeli art music, he spent six years of his adolescence in Eretz Israel, mastering native Hebrew that was far better than his colleagues—an advantage that was evident in his vocal works. Seter taught at the Tel-Aviv Conservatory and Academy of Music (today, affiliated with Tel-Aviv University) from 1951 until his retirement in 1985. A modest figure, he declined any institutional role, and since the late 1960s he also refused to teach composition and rejected commissions. Focusing on composition alone, he gained uncommon admiration among his fellow composers.

Seter’s works from his early and middle periods, 1940-1968, share characteristics with his friends Oedoen Partos and Alexander Boskovich. Many are based on tunes or motives derived from Mizrahi (Jewish Near-Eastern) traditions. Unlike most composers of that time, however, he preferred the use of liturgical tunes over folk ones (hence he did not work with Brakha Tzefira). Further, his textures were mostly polyphonic and heterophonic rather than homophonic (following his studies with Nadia Boulanger, who stressed Renaissance polyphony). He commenced his career with mostly vocal music, such as Motets (choir, 1939-40/1951), becoming known since his 1940 Sabbath Cantata’s premiere (written at the age of 24), which also became a cornerstone in the Israeli repertoire. In the 1950's he wrote mostly chamber music, notably the often-performed Sonata (two violins, 1951-2) Ricercar (strings, 1953-6), and Elegy (violin and piano, 1954). His orchestral pieces were written between 1957 and 1968, among them Variations (1959-60); five versions of Midnight Vigil (1957-1961); ballets commissioned for the company of the legendary Martha Graham, such as The Legend of Judith (1964) and Jerusalem, a symphony for choir and orchestra (1966).

Seter wrote 46 pieces in his late period, 1970-1987, almost half of his oeuvre. Having reached the peak of his fame following the success of Midnight Vigil, he turned to introverted, enigmatic, and exceptionally coherent chamber music in the 1970's and mostly piano music in the 1980's. In these pieces he further developed the use of the original modes that he had invented for Midnight Vigil and Jerusalem. He created during these decades 33 diatonic modes, which served as his core pitch material for 35 of his 46 late works. Each mode comprises an aggregate ranging between 12-25 notes, thus creating a non-tonal harmony unique to Seter. Among his late works are Janus (piano, 1972), Mirvahim (Intervals, 1973), the tumultuous Concertante (first piano quartet, 1973/81), four string quartets (1975-7), and his final piano works such as the stormy Opposites Unified (1984), the spiritual Nokhehut (Presence, 1986), and Nigudim (Contrasts, 1987), which, like Janus, sum up his oeuvre.

(* The photo is taken from Wikipedia. Credit: Yaakov Holander)