The traditional version sung in the Baghdad community, recorded 1961 in Israel.

The medieval Hebrew song Kikhlot yeini and its Purim connections: New sources on its music

Not all traditional Jewish holiday songs have survived in their original performance context or with their melodies of old. The Hebrew song Kikhlot yeini, which used to be performed in Jewish communities on Purim, especially in Germany, is one of those songs. Attributed to Salomon Ibn Gabirol (1012-1058) due to the acrostic “Shlomo,” scholars have concluded that this song is in fact a later creation by a still-unidentified poet also named Shlomo. This peculiar satirical poem straddles the borderline between medieval secular and sacred poetry characteristic of the Andalusian Sephardic milieu. The lyrics cover an apparently earthly topic, but do so with concealed and semi-overt Biblical references.

The earliest appearance of Kikhlot yeini occurs in Ms. Parma, Biblioteca Palatina, Cod. Parm. 1912 (De Rossi 697), which is dated to the 15th century in Germany or France. The song is in fol. 21a-b and follows the daily Birkat Hamazon (grace after meals) without any introduction. It includes only the four stanzas which contain the acrostic and does not start with the refrain. In an important study of this song, Ayelet Ettinger has shown that as early as 1450/1 an imitation of Kikhlot yeini, in fact a mirror poem, was composed in Provence, attesting to the popularity of our song already by the mid-15th century.[1]

In his catalog of the piyyut, Israel Davidson (khaf 242) included no less than nineteen printed sources from a wide geographical and chronological distribution. Moreover, the catalogue of the Institute of Microfilmed Hebrew Manuscripts at the National Library of Israel lists thirty-three manuscripts, from Germany to Baghdad, which include Kikhlot yeni. Also, the David Sasson collection of Hebrew manuscripts includes various Iraqi, Cochini (from Kerala in India), Algerian and Italian manuscripts which include our song. The spread of the Kikhlot yeni text and its documentation are therefore formidable. However, musical renditions of the piyyut are rather rare and will be treated in detail below. For the moment, we will just mention that Kikhlot yeini has survived in two apparently unrelated musical strands which we have labeled “Zionist” and “Jewish” for convenience.

I first addressed Kikhlot yeni in the liner notes to the CD, The Sword of the Dove: Purim Songs in the Sephardi Tradition (2000) by the Boston-based ensemble Voice of the Turtle. The reason for its inclusion in that CD was simple: the song appears in volume IV (no, 181) of Isaac Levy’s massive Antología de la liturgia judeo-espanola (10 vols. 1964-1980), which served as the repository for the repertoire in this album. Since then the Israeli websites Invitation to Piyut and Zemereshet have addressed this song, providing new information, but still leaving much to be said. That the major Hebrew websites respectively dedicated to religious and secular songs included Kikhlot yeini in their databases speaks to the ambiguity with which this unique song has been endowed in the course of the generations. The time has come to set the record straight, and Purim is the most appropriate time for carrying out this task.

The Text

The song as known today consists of an opening refrain and five stanzas of four verses, with the rhyme scheme AAAX, BBBX, CCCX, etc. The fifth stanza (opening with the word nazir [eremite], leading some sources to name the author as Shlomo nazir) may be a later acquisition for, as we have noticed, it does not appear in the earliest manuscript version. The lyrics of Kikhlot yeini tell a story, as follows: a friend of the poet called Moshe (Moses) has invited him to a banquet. The poet was expecting to be served wine as is customary, but water (or watered down wine) is served in its stead. His eyes burst into watery tears. After comparing his host to the Biblical Moses (who had, according to the poet, issues with water), the poet scolds Moshe. In the last verse, the poet expresses the malicious hope that the host should be sworn to abstain from wine, like the Rechabites (compare with Jeremiah 35:4).

The sonic interplay between the words yeini (my wine) / ‘eyni (my eyes) is the basis of the opening refrain. The word water (mayim) becomes the ending of all the stanzas except one. The aesthetics of this song, its form (a simplified muwashshah), meter and rhyme pattern, betray its Sephardic origins, although other options (such as Italian) cannot be discarded. The unproven attribution to the medieval Andalusian Hebrew poet Salomon ibn Gabirol, which we see as early as 1513 when the text of the song was printed for the first time (see below), is therefore not farfetched. This attribution may however have been a stratagem to endow the song with the prestige of that medieval Sephardic poet. The medieval Andalusian pedigree of the song is also echoed in the narratives associated with the song in Zionist circles, where it is variously attributed to Sephardic or even Yemenite origins, as we shall see.

Kikhlot yeini text, Hebrew then English translation

כִּכְלוֹת יֵינִי תֵּרַד עֵינִי

פַּלְגֵי מַיִם פַּלְגֵי מַיִם

שִׁבְעִים (= יַיִן) הֵמָּה הַגִּבּוֹרִים

וְיַכְחִידוּם תִּשְׁעִים (= מַיִם) שָׂרִים

שָׁבְתוּ שִׁירִים. כִּי פֶה שָׁרִים

מָלֵא מַיִם מָלֵא מַיִם

לֶחֶם לָאֹכֵל אֵיךְ יִטְעַם.

אוֹ אֵיךְ לַחֵךְ מַאֲכָל יִנְעַם.

עֵת בַּגְּבִיעִים לִפְנֵי הָעָם.

יֻתַּן מַיִם יֻתַּן מַיִם.

מֵי יַם סוּף בֶּן עַמְרָם הוֹבִישׁ.

וִיאוֹרֵי מִצְרַיִם הִבְאִישׁ.

אָכֵן כִּי זֶה משֶׁה הָאִישׁ.

יִזַּל מַיִם יִזַּל מַיִם.

הִנְנִי רֵע לִצְפַרְדֵּעַ.

עִמּוֹ אֶזְעַק וַאֲשַׁוֵּעַ.

כִּי כָמוֹהוּ פִּי יוֹדֵעַ.

שִׁיר הַמַּיִם שִׁיר הַמָּיִם:

נָזִיר יִהְיֶה לִפְנֵי מוֹתוֹ.

כִּבְנֵי רֵכָב יִהְיֶה דָּתוֹ.

יִהְיוּ בָנָיו וּבְנֵי בֵּיתוֹ.

שׁוֹאֲבֵי מַיִם שׁוֹאֲבֵי מַיִם:

When my wine was consumed, my eyes drip

pools of water, pools of water

Seventy (= 70 is the gematria of yain, wine) heroes they were

Wiped out by ninety (= 90 is the gematria of mayim, water) officers

I have left off singing, for the mouths of singers

are filled with water, filled with water.

Bread to eat — how pleasant it is!

But how can a meal taste good to the palate

When the wineglass in front of the people

Provide water, provide water.

The Sea of Reeds the son of Amram [Moses] dried

And made the Egyptian Nile stink.

Who was this man Moses who

Drew water [from the rock], drew water.

I am a friend to the frogs

He likes water,

No-one knows the song of water

Better than he.

He'll be a holy hermit before his death

Like Yitro’s descendants

He and his household will become

Drawers of water

The Zionist version

We shall start from the end of the story with the “Zionist” chapter of the song, the most recent one. Kikhlot yeini has been documented since the beginning of the twentieth century in Palestine or in connection to Zionist circles abroad. It was already included in the early American Hebrew songster, Qovetz Shirei Tziyyon ve-Shirei 'Am, edited by Yossef ben Yehuda Magilnitzky (Joseph Magil, Collection of Zionist and National Songs, The Best and Most Popular Songs of Famous Poets in Hebrew, English and Yiddish,8th enlarged edition, Philadelphia,1909, pp. 38-39, titled “Shir ha-mayim”) without the melody. It is attributed to Ibn Gabirol and prefaced with the following note: “sing it with the known melody.” What could that melody be?

A viable answer can be found in the most important source for the study of the state of Kikhlot yeini at the beginning of the 20th century, Abraham Zvi Idelsohn’s pioneer songster for schools, Sefer hashirim (Jerusalem, 1912). Idelsohn included two melodies of the song, attributing the text, as customary, to Ibn Gabirol. The first melody, no. 38, p. 31, titled “Shir ha-mayim,” has in its title the indication “ne’imah mekubelet” i.e. “known (or common) melody.” The second one, no. 38a, p. 32, also titled “Shir ha-mayim,” has the indication “ne’imah ‘amamit,” i.e. “folk melody.” While only Idelsohn has documented the “common” melody (as far as we currently know; this may be the melody that Magilnitzky refers to as “the known melody”), the “folk” one became widespread, indeed as a Hebrew folksong, in the Yishuv. Later on, in the young State of Israel, the song continued to be performed in youth movements as well as by professional singers.

A performance from oral tradition of Idelsohn’s second (“folk”) melody, sung by Ezra Kadduri (b. 1913) with the veterans of the Ha-Maḥanot ha-Olim youth movement accompanied by Rami Bar-Giora on accordion, was recorded by Yaakov Mazor (NSA, Y 6317/1, Jerusalem, August 17, 1996). This recording appears in the JMRC CD Nights of Canaan: Early Songs of the Land of Israel (Anthology of Music Traditions in Israel 12). In his liner notes Mazor writes: “One of the oldest songs in the [modern] Hebrew repertoire. The author's name, Shlomo, is spelled out in an acrostic; the poem was formerly attributed to the great Spanish-Jewish poet Solomon ibn Gabirol (1020-1057). The song, with the melody, was published at the time of the Second Aliyah (1905-1914), but was probably already being sung on the eve of the immigration of the ‘Biluyim’ [an early movement of immigration to the Land of Israel, beginning in 1882]. During the 1920s and 1930s the song was sung in the Lower Galilee and in several youth movements - the Jerusalem Ligyon ha-Ẕofim [a youth group that split off the Scout Movement], Ha-Hugim and Ha-Maḥanot ha-Olim. Often sung antiphonally, it remained popular in the youth movements during the 1950s.” This melody is also the one transcribed and published by Isaac Levy as a Sephardic religious song and recorded by Voice of the Turtle in 2000.

In the 1950s and 1960s Israeli folk singers, some of whom were active at that time in the USA rather than in Israel, embraced the 'folk' melody version of Kikhlot yeini and recorded it as an “Israeli folk song,” in the style that would accompany a folk dance. Geula Gill recorded one of the earliest commercial versions (1958), arranged and accompanied by Dov Seltzer, for the legendary label Folkways (Track 12 on the long-play Yemenite and Other Folk Songs, Folkways Records, FW 8735). Aharon Tzadok was another agent in the dissemination of the song. It appears in his 1960 album Various - Songs Of Israel (Oriole MG 10027) and in the 1963 Israel in Song and Dance (Makolit). Also Ran Eliran included the song in his 1962 New Sounds of Israel (where his name appears as “Ron”). The legendary Shoshana Damari also recorded the song for broadcast purposes in Israel. Her version, arranged by Moshe Vilensky, was recorded in 1957 (NSA, K-05855-01-A). Most of these performers (except for Eliran) were of Yemenite or Central Asian background and their energetic performances, with strong emphasis on the pronunciation of the guttural letters of the Hebrew alphabet, endowed the song with an “Oriental” flavor.

So far we have covered the modern Zionist story of Kikhlot yeini. However, what about its previous “Jewish” life?

The Jewish versions

Ashkenazi lineage

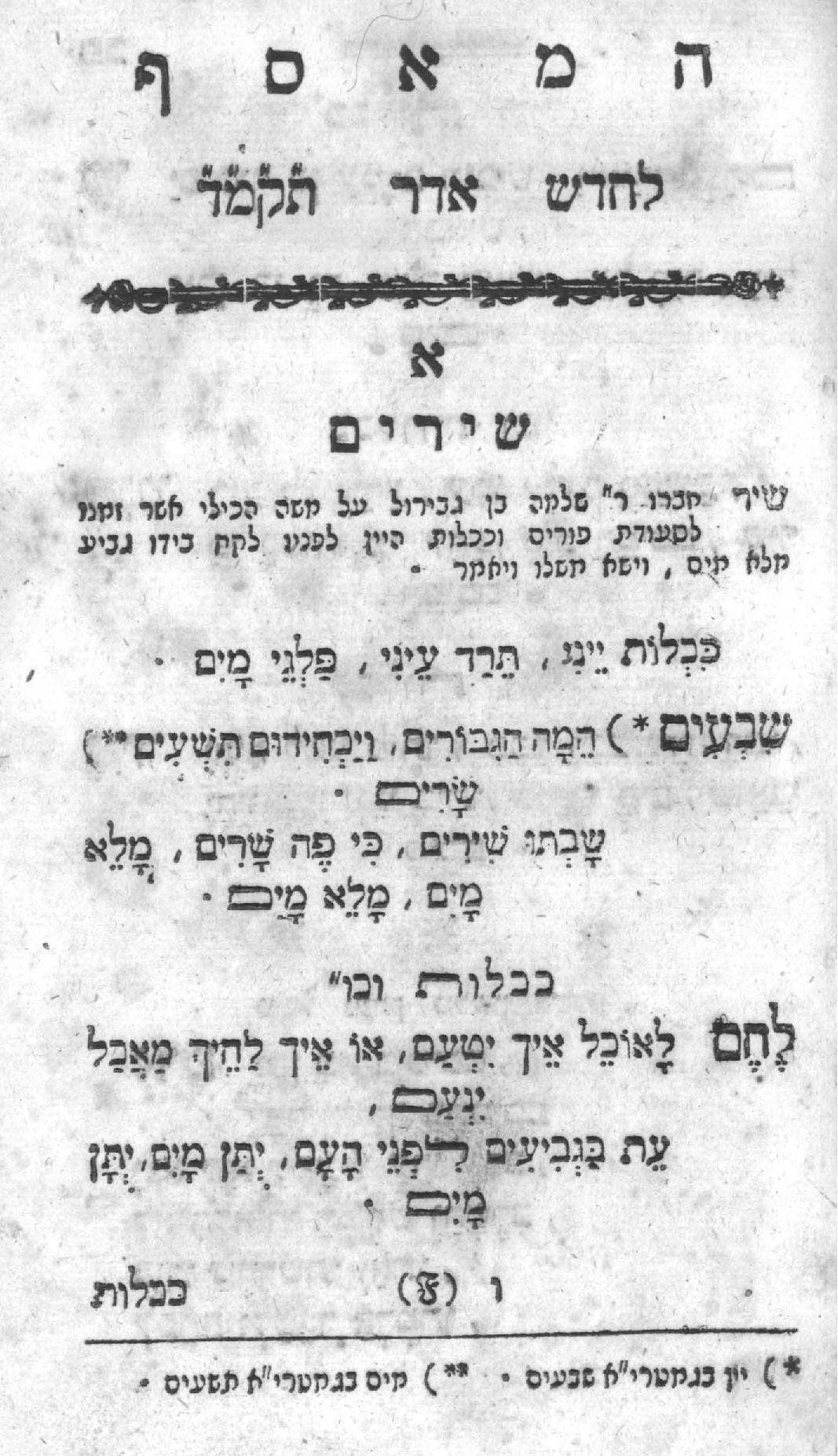

Ayelet Ettinger (note 1 above) remarks that in spite of its lay subject, which includes a critique (and curse) of the miser host Moshe, the jolly atmosphere that the performance of Kikhlot yeini must have generated made it appropriate for singing during the holyday of Purim. The earliest printed version of the song appears preceding Masekhet Purim, a satire of a Talmudic tractate to be “studied” on Purim, by the Italian-Provençal Rabbi Kalonymus ben Kalonymus ben Meir Hanasi, who lived in Provence, Rome and Catalonia (1286/7-after 1328). Written between 1319 and 1322 while its author was living in Catalonia, Masekhet Purim was printed for the first time in Pesaro (1513) and Venice (1553) with our song appearing as an opening. The introduction to the poem in the Venice edition (we had no access to the earlier version) reads as follows:

“song composed by R. Shlomo Ibn Gabirol about Moses the miser who invited him to a Purim festive meal and when the wine was consumed he served him a cup full of water and he raised [words] of his own and he said…”

We can see that the alleged attribution of the song to Ibn Gabirol was already widespread as early as the 16th century.

The persistent circulation of Kikhlot yeini in Germany and Italy through the centuries is well documented. Some sources are manuscript copies of prints, such as Ms. New York, Jewish Theological Seminary 1513, a copy of the Venice edition of Masekhet Purim of 1553, showing perhaps that the printed edition was hard to acquire, or Ms. Moscow, Russian State Library, Ms. Guenzburg 280/5, Italy, 18th century, titled Masekhet Purim u-ma’ariv le-leil Purim keminhag ha-ashkenazim.

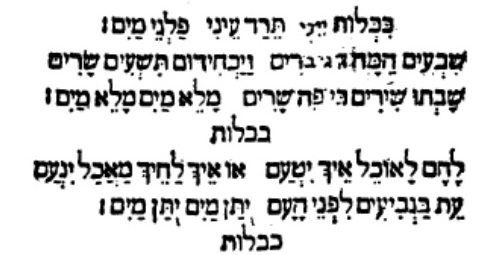

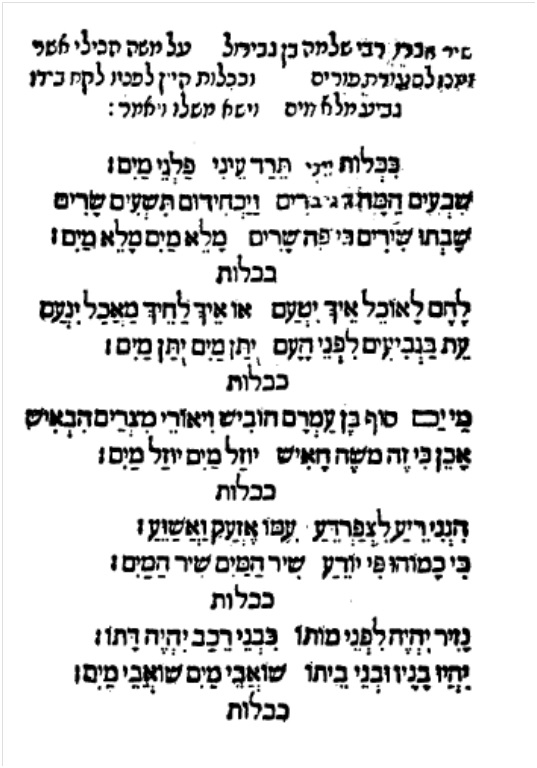

The publication of Kikhlot yeini in the pioneering literary journal of the Haskalah movement, Ha-me’assef (Adar 5544 [March 1784], pp. 81-82) is also worth mentioning and shows the popularity of our song. Here the piyyut is given the same introduction as in the Venice edition, from which it appears to have been copied.

In his Talmudic notes of his studies in Mainz over 1818-1820, a student named Leib Wormser of Fulda (probably R. Isac Löw Matthes Wormser, 1768-1847) copied the text of Kikhlot yeini for his own records in the back of his notebook, perhaps because he learned the song during his sojourn (Ms. Los Angeles - University of California 828, bx. 6.7). Another clear reference to Kikhlot yeini in a German-speaking region is a Hebrew song printed in the anthology of Hebrew texts for the young, edited by Mendel E. Stern, titled Kochbe Jitzhak: Ein Sammlung ebräischer [sic] Auffässe… 6 Heft (Vienna, 1846), pp. 25-6. The title of this poem reads “On Moshe Ha-kilai who ate a great number of bugs and Ibn Gabirol,” an obvious reference to the accepted attribution of Kikhlot yeini to that medieval Sephardic poet.

This thick textual documentation of Kikhlot yeini in early 19th century Germany has a musical counterpart to which not enough scholarly attention has been paid. Two music manuscripts, one dated in 1833 and the other in the first third of the 19th century, include two close variants of a melody that was apparently the one customary in German-speaking lands at that time. The first variant (with text underlay in Hebrew characters) appears in Ms. New York, Hebrew Union College, 2757, a Purimshpil written by the cantor Itzik Offenbach of Köln. The second variant (without text underlay) appears in Ms. Cincinnati, Hebrew Union College, Birnbaum collection, Mus 96b, II, 12. This second source is attributed to cantor Israel Lovy of Paris, but most probably was in the possession of cantor Shalom Friede of Amsterdam. Both cantors had a German background.[2]

Offenbach’s version bears the title “Polacco,” and indeed, the melody in 3/4 has the character of a popular polonaise. The song includes a rather amusing middle section without text, either a vocalese or an instrumental passage. We publish here both melodies (here and here) for the first time, edited in their entirety and with the text underlay. This is a unique Judeo-German musical documentation of Kikhlot yeini, a melody that, to our present knowledge, did not survive in oral tradition.

Sephardic lineage

As we have noted, Kikhlot yeini spread also in non-Ashkenazi areas. The medieval Sephardic (or Sepharadized) pedigree of the song led to print and manuscript distribution among Sephardic communities in the Ottoman Empire, independently of its German lineage.

Significantly, the song is included in one of the earliest and most comprehensive printed anthologies of Hebrew sacred poems from Spain, Italy and the Ottoman territories, Shirim u-zemirot ve-tushbahot, edited by Shlomo Mazal Tov (Constantinople, 1545, no. 49, p. 46). The title of our song in this publication is “Another nice [poem] by the rabbi, Rabbi Shlomo z”l [blessed be his memory].” As we can see, there is no mention of Purim. Moreover, the author is not explicitly singled out as Ibn Gabirol, although “Rabbi Shlomo” by default may have been associated at the time with the prestigious Ibn Gabirol.

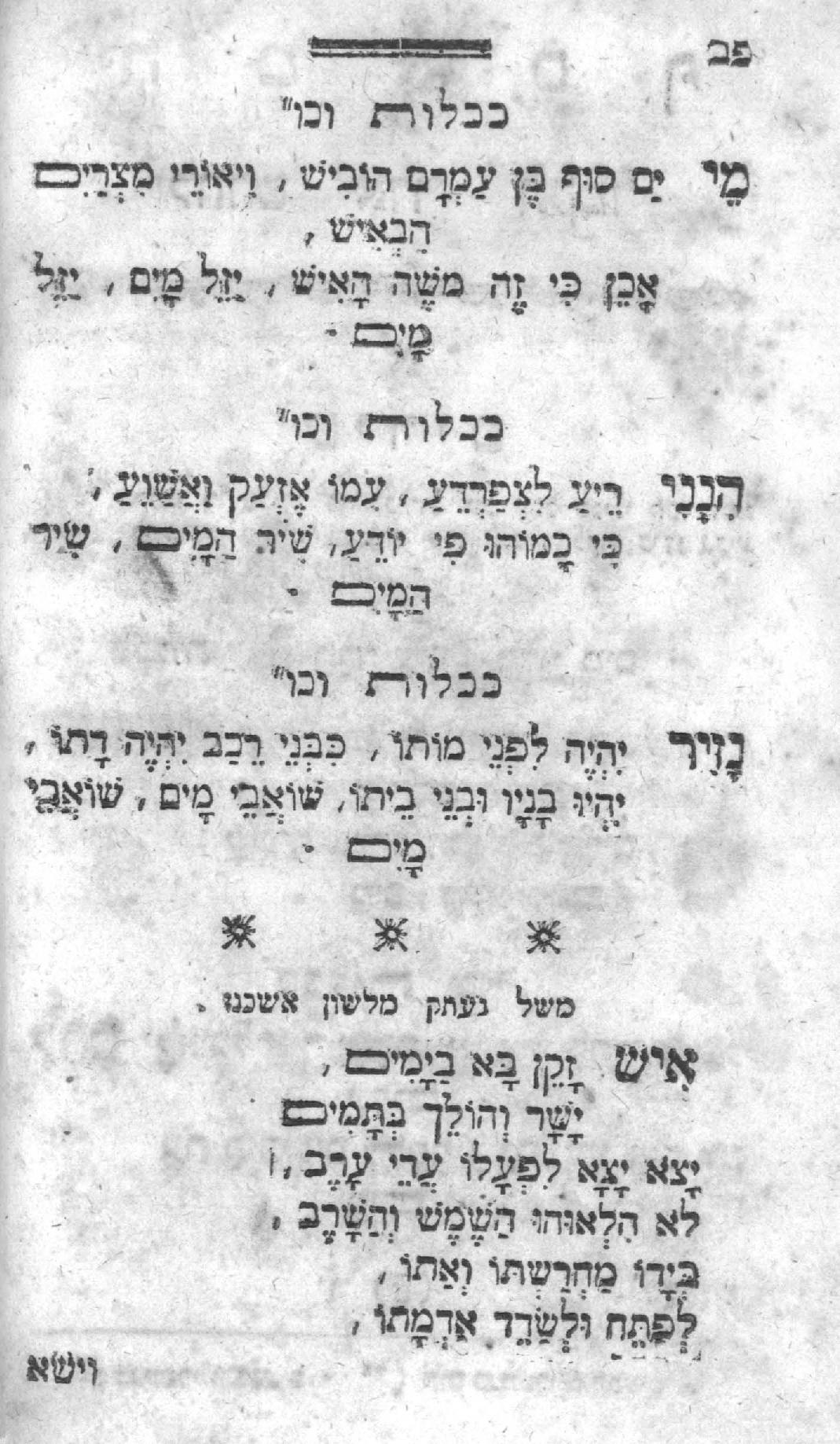

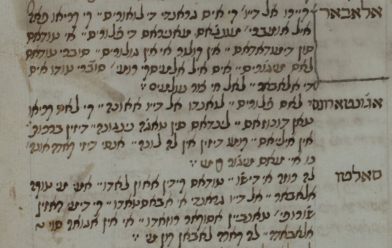

However, in later sources, the relation to Purim reappears in the Sephardic tradition. Ms. Jerusalem, Benayahu NZ 9, titled Bakkashot upizmonim, dated in the 17th century and of probable Baghdadi origins, includes Kikhlot yeini in fol. 76a-b, among the pizmonim for Purim. The song also appears in Ora ve-simha (Livorno, 1786), a collection of Purim songs. Therefore we can deduce that by the 18th century Sephardim sang Kikhlot yeini, at least in Italy and perhaps even in Baghdad, on Purim.

The poem also appears in later Hebrew manuscripts of Persian and Central Asian origin. Ms. Jerusalem, The National Library of Israel, Heb. 4° 8660, a collection of Hebrew poems dated in 1899, mostly by R. Israel Najara, includes Kikhlot yeini with the tafsir (Judeo-Persian translation). Similar occurrences appear in other Mss. of the National Library of Israel, such as Heb. 2 8° 5883 (19th century) and Heb. 2 8° 5813 (dated in 1913).

Fortunately, we possess a precious recording of the oral tradition of Kikhlot yeini from Baghdad, included below, attesting that it was known among the Baghdadi Jews until the last generation of immigrants to Israel in the 1950s. Avigdor Herzog recorded it from Yaacov Huri and friends on November 4, 1961 (National Library of Israel, NSA, CD 4956). This unique melody in (mostly) 10/4 meter shows the musical diversity with which this text has been endowed, in a geographical spread ranging from Provence and Germany through Italy, Turkey and Iraq in its seven centuries-long existence.

A final twist

In 1961 Kikhlot yeini was provided a new melody by no other than Dr. Bathja Bayer, one of Israel’s pioneer professional musicologists, who became head of the Department of Music of the Jewish National and University Library after it was established in 1964.[3] In this capacity, she was also a close associated scholar and editor at the JMRC. Her song titled “Shir ha-mayim” (Water Song) was submitted as an entry to the new, competitive Israel Song Festival of 1961. It was performed by two artists, Illik Raveh and Aliza Kashi, as was customary in that competition.

What is most remarkable about Bayer’s setting is its genetic relationship to the early 19th century German Jewish tune discussed above. The most remarkable resemblance occurs in the setting of the refrain in the 3/4 polonaise style. This meter also stresses the Ashkenazi accentuation of the Hebrew text. Was Bayer aware of this old German tune through the oral tradition of her family? Did she establish a dialogue with the transcription by Offenbach, of which she may have been aware?

We shall never know. What we do know, however, is that the earthly humor of the medieval song Kikhlot yeini continues to appeal to audiences in the modern era, as evidenced by the recent 2012 version by popular Israeli rock musician Berry Sacharov, who has made the song, that is, the 'Zionist' version drawn from Idelsohn's 'folk' melody, part of his concert repertoire. True to the dual secular/religious nature of our song, as noted previously, Sacharov's performance falls within the framework of the piyyut 'renaissance' in Israel, which encompasses both the religious and the non-religious Jewish population, and therefore his rendition cannot be considered as either a 100% religious or secular version.

[1] Ettinger’s detailed commentary of the text of this song and its Biblical and Talmudic sources is highly recommended. See, Ayelet Ettinger, Be-shevah ha-yayin ubi-gnut ha-qamtzanim ba-fiyyut kikhlot yeyni (In praise of the wine and in condemnation of the miser in the piyyut kikhlot yeyni).

[2] For detailed descriptions of these two sources and notes on the cantors related to them see, Israel Adler, (with the assistance of Lea Shalem) Hebrew Notated Manuscript Sources Up to Circa 1840: A Descriptive Catalogue with a Checklist of Printed Sources. 2 vols. Munchen, 1989 (RISM B IX1), nos. 101 and 152.

[3] Bayer was not the only Israel composer who wrote a melody to Kikhlot yeini, Itzhak Edel also conceived a version that, however, had no lasting impact.

Kihklot Yeini - Aharon Tzadok - 1960

Kikhlot Yeini - Bathja Bayer version - 1961

Kihklot Yeini - Ran Eliran 1962

Kikhlot Yeini - Berry Sacharov - 2012