NSA, K 2048/1. A typical if “domesticated” performance by an anonymous group from Moshav Zavdiel (an agricultural settlement of Yemenite Jews in southern Israel founded in 1950), recorded on June 5, 1956. The plurivocal texture (i.e. the improvised doubling of voices in the organum style) and the responsorial singing between the adults’ choir (delet, first hemistich) and the children (soger, second hemistich) reflects the common practice in the traditional performance of this song. On the other hand, the shortness of the recording and its relative “order” betrays the controlled arrangement by the staff of the Kol Israel radio station as much as the budgetary constraints that dictated the restrained use of magnetic tapes.

Elohim Eshala

One Yemenite Jewish Song and its Modern Reverberations

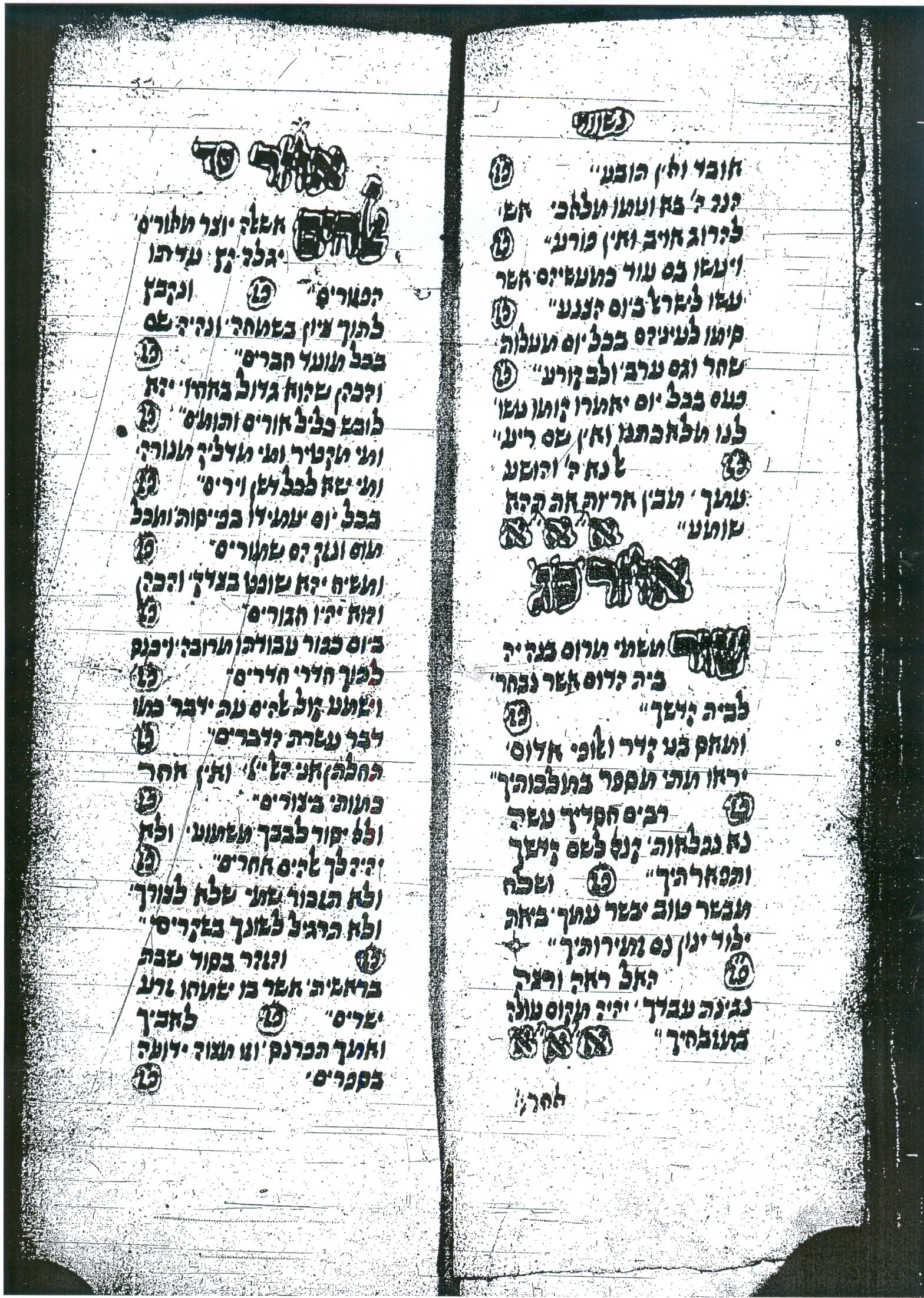

Elohim Eshala is a Yemenite Jewish piyyut included in the Diwan, a compendium of paraliturgical poems whose performance by men and children accompanies the Yemenite Jews in Sabbaths and holidays, as well as their family celebrations, most especially circumcisions and weddings. The Diwan also includes poems for use at any other social occasion when singing and dancing occur. These poems are divided according to their form in three types: Nashid, Shira, and Hallel. A performance usually includes a string of poems from the three types appearing in that order. The Nashid is an introductory poem to the performance. It is sung in flexible rhythm and has an improvisational character even though the basic pattern of the musical phrases is fixed. The Nashid is usually performed responsorially by a soloist and a choir, allowing the soloist to display his vocal abilities through highly melismatic phrases. The Shira comprises the main part of the performance. Unlike the Nashid, the Shirah songs have a fixed beat and meter and it is sung and danced to by a group. The form of most of these songs is that of the Arabic muwashshah[1] or tawashih. A major characteristic of the musical performance of the Shirah is the gradual acceleration of tempo, leading to an ecstatic fast ending. The Hallel (Heb. “praise”) is the poem ending the performance, and is an anti-climax to the Shirah. The Hallel is performed in a plurivocal[2] style that characterizes the performance of Psalms and other prayers in Yemenite synagogues. A blessing to God or to the individual celebrated in the event ends the performance.

Elohim Eshala is a nashid in the classical pre-Islamic Arabic genre, the qaṣīdah,[3] consisting of verses (bayt in Hebrew and in Arabic; Heb. pl. batim) of equal length and meter, each one consisting in their turn of two equal sections (called delet [door] and soger [closing] in Hebrew), with a single ending rhyme running throughout the poem as well as in the ending of the first hemistich of the first verse. The song is performed responsorially. The soloist opens with the first two verses and the congregation/choir answers him (with a second melody) with the third verse that becomes thereafter a refrain repeated after every two verses. Sometime the verses too are performed responsorially, the soloist sings the first hemistiche and the congregation answers with the second hemistich. The author of Elohim Eshala is Yosef Ben Yisrael, a relative of Shalom (or Shalem) Shabazi the greatest seventeenth-century Yemenite Jewish poet.

Performances of Elohim Eshala

In 1936, upon the establishment of the first radio station of Mandatory British Palestine, called in Hebrew Kol Yerushalayim, the then young Israeli singer of Yemenite origin Bracha Zefira, sang Elohim Eshala in a broadcast dedicated to Jewish-Yemenite tunes (see the program of the first week of Hebrew broadcasting below). Two aspects of this (as of now lost) historical broadcast are notable: first that an exclusively men’s song was performed by a woman and for a wide open audience (one has to be reminded that in the traditional Yemenite Jewish community the voice of a woman was technically forbidden for a man to listen to); secondly that the earliest modern Hebrew broadcasts were marked by songs from a distant diaspora, the same diaspora that political Zionism strived to escape. The question is: why?

In 1936, upon the establishment of the first radio station of Mandatory British Palestine, called in Hebrew Kol Yerushalayim, the then young Israeli singer of Yemenite origin Bracha Zefira, sang Elohim Eshala in a broadcast dedicated to Jewish-Yemenite tunes (see the program of the first week of Hebrew broadcasting below). Two aspects of this (as of now lost) historical broadcast are notable: first that an exclusively men’s song was performed by a woman and for a wide open audience (one has to be reminded that in the traditional Yemenite Jewish community the voice of a woman was technically forbidden for a man to listen to); secondly that the earliest modern Hebrew broadcasts were marked by songs from a distant diaspora, the same diaspora that political Zionism strived to escape. The question is: why?

One reason for this phenomenon is the then entrenched perception of the Yemenite Jewish melodies as surviving specimens of great antiquity, going  back (in the minds of romantic Orientalist European Jews) as far as the tunes of the ancient Levites of the Temple in Jerusalem. This hypothesis was grounded on the assumed social isolation of the Jewish communities in Yemen from the surrounding Muslim majority, as well as on the early arrival of exiled Israelites from Judea to the Arabian Peninsula after the destruction of the first Temple in Jerusalem (586 CE). The Zionist nostalgia for idealized Biblical times when the ancient Hebrews worked their land and defended themselves fueled such perceptions. Hence, the broadcasting of Yemenite Hebrew songs such as Elohim Eshala, a text that specifically addresses the returning of the Jews to Zion in messianic times and is set to a melody far removed from contemporary European music aesthetics, was fit to the new circumstances.

back (in the minds of romantic Orientalist European Jews) as far as the tunes of the ancient Levites of the Temple in Jerusalem. This hypothesis was grounded on the assumed social isolation of the Jewish communities in Yemen from the surrounding Muslim majority, as well as on the early arrival of exiled Israelites from Judea to the Arabian Peninsula after the destruction of the first Temple in Jerusalem (586 CE). The Zionist nostalgia for idealized Biblical times when the ancient Hebrews worked their land and defended themselves fueled such perceptions. Hence, the broadcasting of Yemenite Hebrew songs such as Elohim Eshala, a text that specifically addresses the returning of the Jews to Zion in messianic times and is set to a melody far removed from contemporary European music aesthetics, was fit to the new circumstances.

An ambivalent attitude towards Yemenite Jewish song that is still pervasive in contemporary Israeli culture characterized the treatment of songs like Elohim Eshala. Yemenite songs were considered then as too “Oriental” or “strange” by non-Yemenite Israeli listeners and were looked down upon (see the memoires of the Yemenite Jewish musician Yehiel Adaqi). At the same time these songs were embraced and admired by some members of the cultural elite as a desirable component of the new Zionist culture.

A proof of this embracing is the various quotations and arrangements of the melody of Elohim Eshala by Israeli composers of Western art and popular music during the 1950’s. Such arrangements had sometimes an ideological goal: to create a new Israeli sound that will combine modern Western compositional techniques with the “authentic” melodies of the “Oriental” Jews. In the rich selection of recordings that follows this introduction diverse and contrasting readings of Elohim Eshala can be heard. This selection is only a fraction of the eighteen different recordings of this song found in the National Sound Archives of the National Library in Jerusalem. They are a cross-section of this rich and yet problematic musical encounter between the Yemenite Jewish tradition and Western musical techniques.

[1] muwashshah in britannica.com.

[2] About plurivocality: Simha Arom and Uri Sharvit, 'Plurivocality in the Liturgical Music of the Jews of San‘a (Yemen)' in Yuval 6, Jerusalem: The Magness Press, 1994, pp. 34-67.

Sound Examples

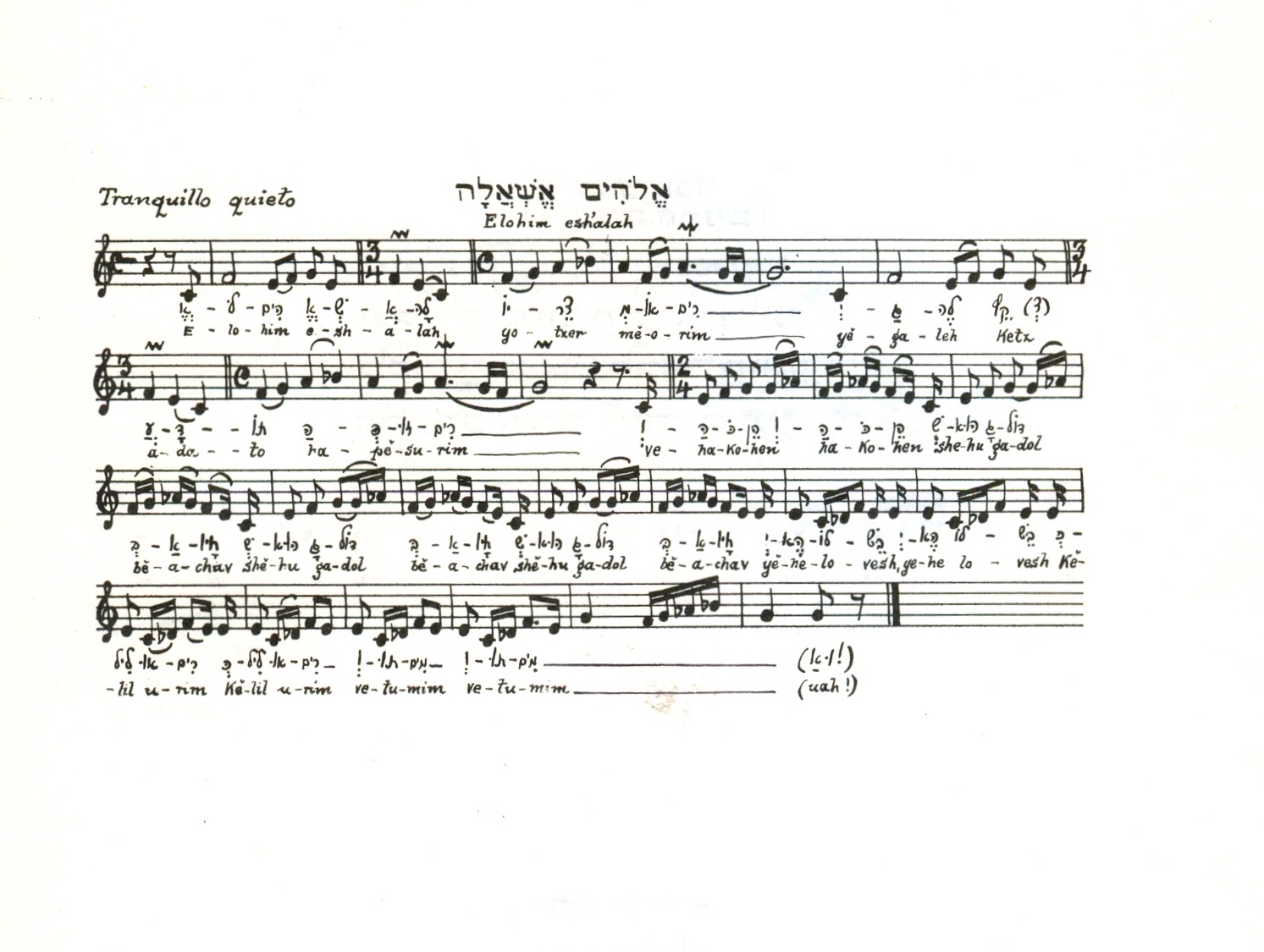

NSA, K-3751/1. Bracha Zefira (1911-1990) with the Kol Israel Orchestra performing the arrangement by Paul Ben Haim (1897-1984) of Elohim Eshala, recorded on December 12, 1956. When Zefira turned in the mid-1940s to Paul Ben Ham to arrange for her the songs of her variegated ethnic repertoire (see her book Kolot rabim), she wanted to upgrade herself after more than a fruitful decade of collaboration with composer and pianist Nahum Nardi. This upgrading meant a more refined orchestral arrangement than the folksy (if sophisticated) improvised piano accompaniments of Nardi. The present recording, which was not released commercially and was used for broadcasting purposes only, shows the singer after the peak of her career. The arrangement by Ben Haim, that includes the first verse, refrain, second verse, refrain, non-sense syllables, is rather uninspired. It is plagued with clichés such as the solo clarinet in the opening that recalls in fact Eastern European Jewish music. The attempt in the first section to create the effect of Yemenite plurivocality (organum) does not achieve the desired goal. The instrumental intermezzi, between the two sections of the arrangement and after the second refrain, are forced on the original Yemenite song, recalling textures from Alexander Uriah Boscovich’s “Semitic Suite” of 1945. A comparison between this recording and the almost contemporary arrangement by Moshe Wilensky (NSA K-334) is instructive. As a composer of popular music, Wilensky had no pretensions in his arrangements. Yet, his take on Elohim Eshala seems much more vibrant and attuned to the original than the one by the canonic art music composer Ben Haim.

Not long after Zefira recorded Ben Haim’s arrangement of Elohim Eshala, another important Yemenite Jewish singer, Aharon Amram, a young newcomer from Yemen in the early 1950s who eventually became one of the most important performers and teachers of the Yemenite Jewish song in Israel (among his students is the late international star Ofra Haza), recorded the song accompanied by a sharqi ensemble (lit. “Middle Eastern” Arab ensemble). This recording of the song represents a totally different development in Israeli culture, one taking place from the 1960s onwards in the peripheries of the state-controlled mass media and small recording industry. Amram’s authentic voice blends here with a non-Yemenite Arabic sound, a musical style brought to Israel by professional immigrant musicians from Iraq and Egypt. This is another hybrid musical product of Zionism, for sure a non-programmed one by any institutional ideology. A similar encounter can be heard in Dahyiani's recording (NSA, CD 1836/8).

NSA, Yc 01175. The singer Tzadok Tzuberi was recorded by Dr. Avner Bahat at the National Sound Archives in Jerusalem in 1977 as part of Bahat's comprehensive research project on the music of the Yemenite diwan carried out in cooperation with Naomi Bahat-Ratzon. This version, as those of the group from Moshav Zavdiel (NSA K 2048) and Aharon Amram provide a glimpse into the traditional performances of Elohim Eshala prior to immigration to Israel.

NSA, K 3877. A choral composition by Joseph Tal (1910-2008) inspired by Elohim Eshala, performed by the Choir of Kol Zion Lagola Choir and recorded on January 23, 1957 under the baton of the composer. This is the third movement of Tal's "Three Pieces for Choir" of 1952. Against most of the widespread (and partial) narratives regarding Yosef Tal’s persona in the historiography of Israel art music, i.e. that of a cosmopolitan, radical modernist detached from the local national concerns, this recording shows Tal’s commitment to the effort of translating “authentic” folk traditions into new music. Of course, the mastery of this German Jewish composer of international stature stands out in his passionate and highly original treatment of the raw material that is far removed from the clichés of other arrangements such as Paul Ben Haim’s (NSA K 3751). Tal keeps four very basic elements of the “original”: 1) the sharp contrast between the first section (nashid style with unclear beat) and the refrain (“Ve-ha-Kohen”); 2) the melodic contour of the Yemenite song; 3) the accelerando towards a peak at the end of the song (here the accelerando occurs twice, in the two repetitions of the refrain); the “non-sense” syllables that are added by the Yemenite Jewish singers at the end of each musical unit, usually “ya ha, ya ha, ya leili.” Within this framework Tal rereads the standard version of Elohim Eshala (compare with NSA K 2048/1) using the wide palette of techniques available to a modern European composer addressing folk materials: static harmonies, ostinati, drones and polyphonic imitations based on distinctive melodic cells from the original tune. Dense textures contrast with ethereal passages adding a further layer to the basic contrasts of the original, i.e. slow/fast and unclear/clear beat. The final result is a gem that was doomed to be forgotten after the 1970s (perhaps with the assistance of the composer himself who did not emphasize in later periods this aspect of his work during the peak of ethnic “Israelism” in the 1950s).

NSA, Jacob Michael Collection, R 0080. This is a copy of the 1958 Folkways release by the Israeli singer Geula Gill “Yemenite songs and other Israeli folk songs.” Gill (b. 1932 in Tel Aviv as Geula Levavi from a family of immigrants from Tashkent in Uzbekistan) is one of the major Israeli artists to have had a long-term and distinguished presence in America. This seminal recording was done when Gill, with her husband then, the notorious composer and arranger Dubi Seltzer, moved to the USA where Seltzer studied composition. They formed an ensemble specializing on Israeli “folk music” called “Oranim Tzabar” playing arrangements by Seltzer and the present recording is one example of their work during this period (1958-1959). Elohim Eshala is the only really traditional Yemenite track in this record, the rest being mostly Hebrew covers from the Judeo-Spanish (Ladino) repertoire and other items then in vogue in the Israeli radio waves. The stress on the “Yemenite” in the title of this long-play appears to be then a strategic decision geared to stress an essentialized “Israeli exoticism” that captivated at the time the American Jewish audience. It is clear that the voices of Shoshana Damari (without the heavy Yemenite accent) and Sara Levy Tanai, voices to which Gill (who is not a Yemenite Jew) was certainly exposed during her youth in Israel, are behind her performance in this track. Moreover, the track includes two songs, the first one being Elohim Eshala with only the opening three batim performed (the nashid part and then the refrain, "Ve-ha-Kohen”). The second song is “Ah! Ofra,” a song popularized by Sara Levy Tanai.

NSA, CD 1836/7. Shlomo Dahiyani accompanied by darbukka sings only the first stanza as a nashid and the rest of the poem as shira with a melody similar to the usual refrain on the third bayit, “Ve-ha-kohen.” Dahiyani does not sing this bayit as a refrain, unlike most other versions of the song. Instead between the stanzas he improvises a refrain on non-sense syllable with ululations of joy (apparently by women) in the background. He sings a selection of stanzas ending with the last one. The three minutes format of this recording and its formal concept is in accordance with the cutting of a commercial 78rpm record. See Dahiyani’s second take on this song in NSA, CD 1836/8.

Second recording by Shlomo Dahiyani

NSA, CD 1836/8. The second recording by Shlomo Dahiyani is similar to the one NSA, CD 1836/7 but is more than double in length. Here Dahiyani is accompanied by a qanun as well as by several percussion instruments included a low drum. These instruments are not characteristic of the Yemenite Jewish tradition and betray the encounter of Dahiyani with Jewish musicians from other Arab-Jewish traditions in Israel, especially Iraqi Jewish musicians. Moreover, unlike the shorter recording the performance develops as a self contained “suite” whose main characteristic is the constant acceleration of tempo ending in an ecstatic peak. This is the most common format of the performance of a shira accompanied by dancing in a joyful celebration. All the stanzas of the poem are sung, and except for the first one that is in the nashid style, the rest are performed responsorially by dividing each baiyt between two soloists and by repeating the first half of each textual unit. The recording is enhanced with the background of a participating audience that adds “ethnographic authenticity.”

NSA, K 334. This release by Hed Arzi (R 304/1) of Shoshana Damari’s version of Elohim Eshala accompanied by the Orchestra of Kol Zion Lagola was recorded in Israel but was intended for the American market (the label is in English only) distributed in Arzi Records in New York. The painstakingly orientalistic orchestration by Moshe Wilensky (1910-1997), a mix of Hollywood’s most common clichés signifying “Orient” and late Romantic techniques employed to represent the “Middle East,” underscores the composer's classical European upbringing in inter-war Warsaw as well as his American experience of 1949-1950 when he toured with Damari and recorded with her in New York City. Notably, Wilensky is credited in the label as the composer of this piece. This thoroughly abridged version, the one to which most of the American Jewish and Israeli audiences were exposed to in the 1950s, abides by the music industry's standard of three minutes length per item. Still, it preserves much of the original elements of the traditional song. It includes only the first four batim (verses) of the poem: the first two ones are in the nashid style and the lively (and rhythmical) melody of the refrain (“Ve-ha-kohen”) is applied to the third and fourth verses. Wilensky masterfully creates a “cloudy” accompaniment to the first two verses (no clear beat or harmony is heard except for the cadences at the end of the phrases), a sort of imitation of an "authentic" heterophonic performance. The second pair of verses on the contrary are a rapturous dance including a steady acceleration that climaxes with the very last sound. This acceleration is, as can be seen in the recording of Shlomo Dahiyani (NSA, CD 1836/8), a basic trait of the Yemenite (Jewish and Muslim) performance practice of this type of poetry. Also worth noticing is that Damari sings with a pronounced Yemenite Hebrew accent, a feature that she will not stress later on in her career.