Asher Shimon Mizrahi was born in the old city of Jerusalem in 1890 to father Yitzhak Mizrahi, who was a well-known torah scholar and teacher. After the first few years of Asher’s life, his family moved outside the old city walls and built a new home across from the Sephardic Synagogue in the newly established neighborhood of Montefiore, known today as Yemin Moshe. The Mizrahi family made their living by renting out the use of their wooden oven to community members for cooking and baking. Residents of the neighborhood would bring biskochos (cookies), borrekas (stuffed phyllo dough pastries), and Hamin (a slow-cooked stew that is the staple meal for Shabbat) to be cooked in the Mizrahi oven.

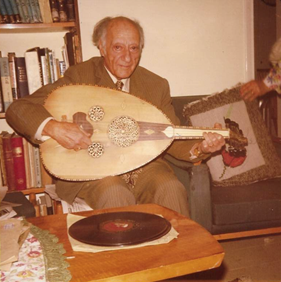

From an early age, people in the community took notice of Asher Mizrahi’s pleasant voice and musical talents, and he began to earn money working as a local hazzan and as an ud musician. He also supported himself by selling embroidered “taligas,” or prayer shawl pouches, and ornamented curtains for the ark in the Synagogue. Asher was married at a young age to Rachel, a member of of the house of Elishaich, with whom he had two daughters, Rebecca and Sara.

During the Balkan War (1912-1913), many young Jewish residents of Jerusalem fled the city or hid in order to escape the Turkish draft. Rabbi Eliyahu Panigel, a wealthy merchant and admirer of Asher Mizrahi, helped him to escape from Eretz Israel on a cargo boat exporting oranges to Malta. The small Jewish community of Malta wasn’t able to utilize the services of a hazzan of Mizrahi’s level, and therefore he ultimately chose to settle in Tunisia. Asher Mizrahi assimilated very quickly into Tunisian life and culture, and within a year, he was able to bring his wife and children. In Tunisia he taught piyyutim and Jerusalemite songs to the locals. He also composed and exported to Jerusalem many songs about his yearning for Zion, which were enthusiastically received and performed at community baqqashot gatherings. Mizrahi was also heavily entrenched in the cultural life of the Muslim community in Tunisia and composed many songs in Arabic.

In 1919, with the conclusion of WWI and the release of the Balfour Declaration, Asher Mizrahi decided to return to Jerusalem with his family, which now included two more children—Yehudit and Yitzhak. Upon his return to Yemin Moshe, Mizrahi became a highly respected figure in Jerusalem's musical life, writing songs in Ladino, composing new piyyutim, and performing and teaching. Yaakov Yehoshua writes in his book Yaldut b’Yerushalayim ha’Yeshana, “Asher Mizrahi was the most famous of the instrumentalists and paytanim that performed in Jerusalem. He was known and admired even by Arabs in their cities and small towns, and for the women of Jerusalem, who in the meantime had become old and gray; Ashriko Mizrahi was one of the musicians who especially stood out. All of us, men and women, were infatuated with him because of his handsome looks. He was dark, with green eyes, and a pleasing voice that captured one's heart. Unlike other musicians whose dress was sloppy, Ashriko was strict with his dress; his neck was always covered with a white or colorful silk kerchief, which was also a way of protecting his throat from the night’s chill. When he would enter a room with his musician friends, all present would rise in his honor. His ud was a gift from the house of Shachiv, and was wrapped in a white silk pouch. He had a slow and measured walk that communicated recognition of his self-worth.” In addition to his many other business endeavors, Asher Mizrahi was certified as a butcher, but never pursued the career.

In 1926, he was invited to perform at the great Synagogue Eliyahu Ha’Navi in Alexandria, Egypt. In awe of Mizrahi's talent, the Jewish community of Alexandria asked him to stay and serve as their cantor and butcher, but he declined their generous offer. The 1929 Palestine Riots broke down the delicate relationship that had been built between Jews and Arabs living in Eretz Israel. Security officials suggested that Mizrahi stop using the tarboosh (a Turkish instrument) in his performances, which was one of the central instruments in his ensemble. The Arab public took this move as an expression of Mizrahi’s support for Zionism, and as a result he received many threats which caused him to leave Eretz Israel and return to Tunisia. Mizrahi had a seamless return to Tunisia. He gained fame through his diverse body of songs in Arabic, and became one of the leading composers of Tunisian song. The great Tunisian singers of the time, both Muslim and Jewish, performed his songs, most notably the Jewish singer-actress Habiba Masika, also known as “Havivat el kol” (a double-meaning, implying 'friendly to all' and 'friendly voice'). Jesse Riachi, in a story about the first meeting between Habiba Masika and Asher Mizrahi recalls, “She stopped him, stood by him and with smiling eyes and said, ‘Mr. Asher, would you be so kind as to teach me how to play the ud?’ ‘Who are you?’ he asked. ‘I am the niece of Laila Sefeg (herself a famous singer), how can you refuse?’ Asher taught her to play the ud, and other basic instruments of song and dance.” Upon Masika’s tragic death at the young age of 35, Mizrahi composed a tribute in her honor.

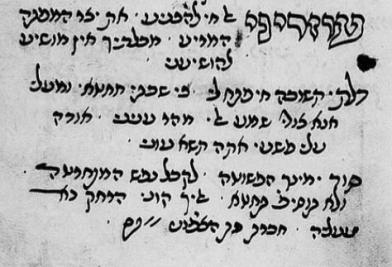

In the early 1930s, Asher Mizrahi traveled to Paris to make a recording with fellow musicians Sheikh El-Afrit, Shafia Rushdie and Dalila Masoud Achabib. The film company Pathè filmed a short movie, more like a clip, with Asher Mizrahi singing one of his songs and accompanying himself on the Ud. This short film was screened at cinemas as a preview to the main attraction. In the late 1930’s he was accepted as a member of the French Union of Artists and Composers. In 1946, Asher Mizrahi released a collection of his piyyutim, “Ma’adenei Melech,” published by Machloof Nijar Masousa.

Hemdi Abasi’s notes in his book, “Tunis Shara v’Rokedet,” that Sheikh El-Afrit owes his most famous song, “Te’Saper o’ Titkarev,” to Asher Mizrahi. In this way, even songs that were written in Arabic, for an Arab audience, expressed Asher Mizrahi’s longing for his homeland. Hemdi Abasi also recounts that Asher Mizrahi’s voice was one of the first to be aired on the new broadcast station established in Tunisia. The first song of his released on air was, “Utini busa min pumek, Ishwa damek ya Mahlook” (“Give me a kiss from your mouth, God how beautiful you are”), which became very popular and remained on the lips of all who heard it. Tunisian Radio allowed Asher Mizrahi to participate in a special program in Hebrew, broadcast every Monday. When one of the Monday programs coincided with Shavuot, he refused to appear, and the radio station terminated his contract.

Jewish-Tunisian singer Raul Jorno was a great admirer of Asher Mizrahi. In an interview on Israeli television for the movie series “Mikratago l’Yerushalayim” (from 1993). Raul Jorno recounted that Asher Mizrahi was “one of the three greatest composers in Tunisia”. He noted that “only Asher Mizrahi, only he was able to sing in the Baghdadi style—one of the most complicated kinds of Arabic song.” Asher Mizrahi won several awards, the most noted of which was the “Nishan Ip-Tiher,” awarded to him by the Tunisian government.

In February 1957, a year after Tunisia gained independence from France, Habib Burgiba, the president of the new Republic visited the school “Or Torah” in the Jewish quarter. Sharel Hadad, the president of the Tunisian Jewish community wrote in his book, “Tzarfat—Israel—Tunisia, Shalosh Ahavot” (“France—Israel—Tunisia, Three Loves”) “Asher Mizrahi accepted his [the President's] request and composed a song in Arabic especially for his visit. The President, Habib Burgiba enjoyed it very much and was particularly surprised by Mizrahi’s delicate and native Arabic.”

In 1967, with help of Sharel Hadad, who was also a lawyer, Asher Mizrahi returned to Israel after almost forty years living abroad. He arrived in August, only a few weeks after the Six-Day War. While in Marseille, Asher Mizrahi managed to make a final recording of several songs and the Avodah service for Yom Kippur, as 'payment' to Sharel Hadad for helping to secure his immigration papers. Asher's health began to deteriorate, and he could no longer tour his childhood neighborhood of the old city, the Kotel and Yemin Moshe. By the fall of 1967, Asher was bedridden and could not participate in the hakafot (practice of carrying the Torah scrolls in circuits) for Simchat Torah, which was held next to the Jaffa Gate. Asher Mizrahi passed away the day after that Simchat Torah celebration.

In the same year, a new edition of his book “Ma’adenei Melech' was printed. His book was distributed on Shabbat Zachor, a day dedicated by many synagogues to the memory of Asher Mizrahi. Eulogies were given in Asher's honor by the great Sephardic Rabbis of Israel, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, Rabbi David Shalosh, Rabbi David Gaz, the Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem and Rabbi Eliyahu Pardes. Today, sixty years after the first release of “Ma’adenei Melech' we still hear Asher Mizrahi's piyyutim in many of the Sephardic and Mizrahi communities in Israel and around the world.