Jewish Music Collections of the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine in Kyiv, aka the “Beregovski Collection,” [henceforth: the Kyiv collection] has attracted the attention of musicians and scholars of Jewish music ever since they resurfaced in the aftermath of the downfall of the Soviet Union. Different and at times contradictory narratives surround the attempts by individuals and institutions to secure public access to this unique historical repository of sound and ethnographic documentation of Eastern European Jewish music and folklore. The complicated paths of encounter between scholars from around the globe and the Kyiv collection continue to this day, three decades after it started.

The Jewish Music Research Centre (JMRC) is one of the institutions that has invested efforts to access the Kyiv collection for the benefit of the wider scholarly and artistic communities and the broader public. The present report, prepared on the launching of the webpage dedicated to JMRC projects related to the Kyiv collection, provides an accurate record of the institution’s past involvement with this resource. At the same time, this document traces plans for the JMRC’s engagement with materials of the Kyiv collection in the future.

In the summer of 1994, the then-director of the institution called at that time the Vernadsky Central Library of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences in Kyiv, Prof. Alexii Semenovich Onishchenko, visited the Jewish National and University Library (JNUL [today the National Library of Israel]) in Jerusalem. As the JMRC was embedded within the JNUL, its director, the late Prof. Israel Adler, hosted Prof. Onishchenko at the National Sound Archives (aka “Phonoteque”).

Onishchenko mentioned to Adler on that occasion that the Vernadsky Library held a substantial collection of wax cylinders of Jewish materials. Soon after, in 1995, Adler traveled to Kyiv in pursuit of the collection. Realizing while in Kyiv that the cylinders were indeed the famously “lost” Beregovski collection, Adler engaged in a public relations and fundraising campaign to mobilize institutions and individuals in order to make the Kyiv collection available to the public. Soon after a formal agreement was signed between the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences and the JNUL for the exchange of materials and information and collaboration in the processing of the collection.

In retrospective, Adler’s overenthusiastic reaction shows that he was unaware of parallel efforts made to disseminate the existence of the Kyiv Jewish collections (although not necessarily the music ones). His enthusiasm could be explained by the excitement generated by the opening of the Russian and Ukrainian archives of Judaica to Israelis in the post-Soviet period. Had Adler read Zachary Baker’s 1992 article on the Jewish collections in Kyiv, he would have realized that “To anyone familiar with the background of the Kiev Institute’s library [i.e. Institute for Jewish Proletarian Culture], the offhand assertion that it had ‘never been described in print’ is inaccurate. Indeed, there is a considerable body of literature regarding these collections, much of it published well before 1989. Perhaps the claim was made in ignorance of the connection between the newly discovered [Vernadsky] library materials and those that were assembled in Kiev during the firsthand inspections of the collections.” (Zachary M. Baker, History of the Jewish Collections at the Vernadsky Library in Kiev,” Shofar 10, no. 4 [1992; Special Issue: Yiddish and Ashkenazic Studies], pp. 31-48, quote in p. 34 and also references to music collections in p. 45 and note 27)

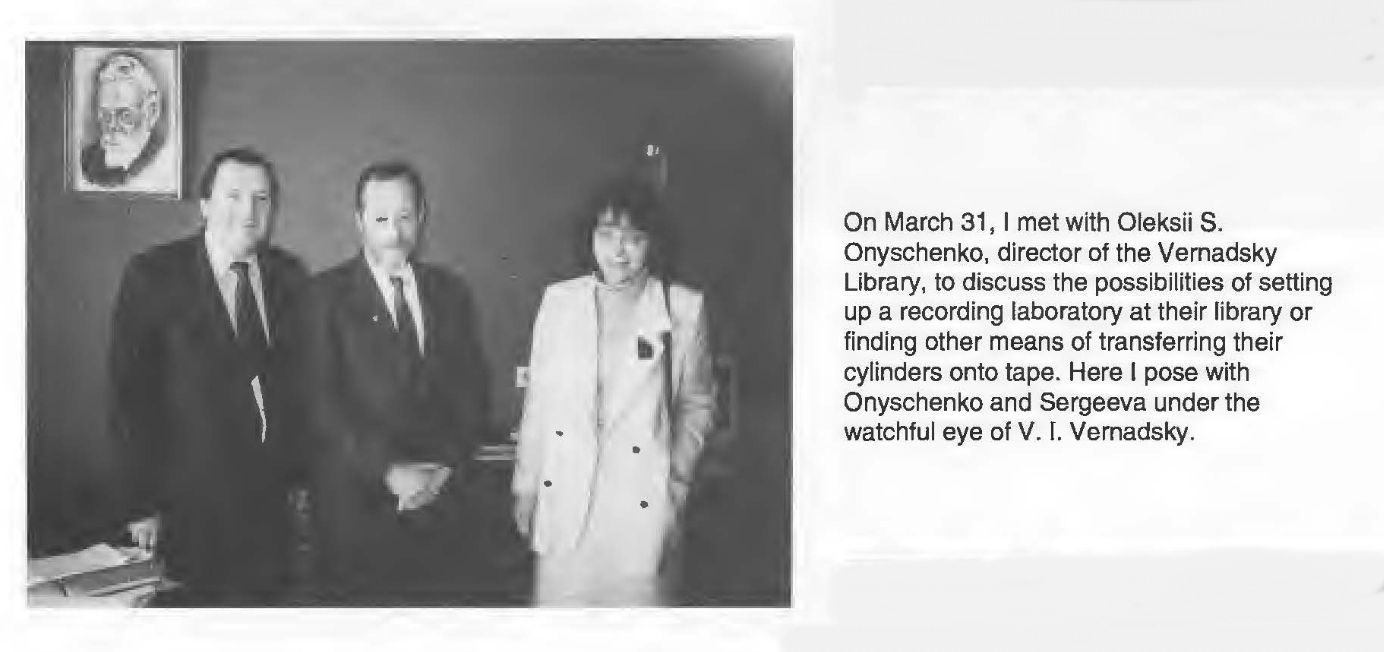

Adler could have also read the 1994 report by Joseph C. Hickerson, at the time the Librarian and Director of the Archive of Folk Song at the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress, about his visit to the Vernadsky Library in Kyiv in late March 1994 published in the Folklife Center News (16, no. 3 [Summer 1994], pp. 5-7). This report is not only illuminating for the early pictures of Dr. Irina Sergeyeva and Dr. Lyudmila Sholokhova (see below) illustrating it, but most importantly for one picture that speaks millions. It shows that a major institution in “the West,” the Library of Congress, also knew about the recorded Jewish music collection in Kyiv. The LoC was negotiating the possibility of assisting the Ukrainian institution to transferring the cylinders (still not digitizing!) to tapes just a few months before Prof. Onyschenko’s visit to Jerusalem. Thus, we know now that many different negotiations and international connections were forged at the same time around this recorded music collection, evidently without the parties’ knowledge of one another’s dealings with Kyiv. When Adler suggested, just a few months later, the good services of the Vienna Phonogrammarchiv, mobilizing even the International Music Council of UNESCO as mediator, the Vernadsky Library had already made its decision, we now know, to engage in the digitization of the collection with its own technological personnel and means.