This piece is based on Arno Nadel’s arrangement of a Hasidic tune published as Chassidisches Lied (ohne Worte). (Nadel 1905)

Arno Nadel’s Chassidisches Lied

In Stutschewsky’s album the order of the title was turned upside down, Lied ohne Worte (Chassidisch). Stutschewsky’s title stresses the characteristic wordlessness of the Hasidic nigunim. His own words regarding this concept are pertinent here.

While among other nations the song usually appears with words – exceptions are rare – among the Jews we find numerous “songs without words” as a typical genre. Out of the singing without words (both among the Hassidim and among the people’s masses) sprouts the main Jewish characteristic, that of total dedication to the singing itself filled with dwejkuth and conviction. In this field the Jews thrived and turned the Song without Words into pure music (is that a coincidence that a converted, assimilated Jew – Felix Mendelssohn wrote “Songs without Words” for piano?). (Stutschewsky 1958: 59)

In Hasidic thought, expressing the yearning for a total spiritual experience is beyond words, even those of prayer. Experiencing dvekut, i.e. the cleaving with God, gives birth of the nigun and its performance is the vessel through which the hasid may achieve this desired mystical state (Ben Moshe 2015). The characteristic use of meaningless syllables (bai-bai, boi-boi, ya-di-dai, tari-tai etc.) in Hasidic singing connects this song to the previous one, the Die alte kasche’s refrain.

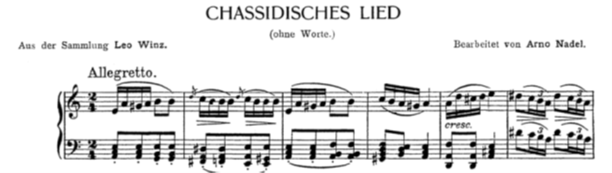

Nadel’s arrangement for piano solo shows the same succinct approach as Stutschewsky’s album as well as Kisselgoff’s version of the same nigun in the Lider-zamelbukh – the twelve-bar tune is neither developed nor repeated with variations. Nadel’s compositional style is post-Romantic, supportive in harmony, rhythm and even in occasional in unison between the bass and the right hand’s melodic line. The A minor tonality is reinforced in the harmonization with very minor deviations, such as the ornamental chromatic descending movement of the left hand in the second bar.

Stutschewsky’s tune is identical to Nadel’s, even in the farshlag decorations (dreidlakh in Yiddish). Played on the violin or cello, the dreidlakh adds a klezmer touch to the interpretation. However, Stutschewsky’s harmonization in the piano part is extremely different from Nadel’s banal one. The tonic A chord is avoided throughout the tune’s arrangement in favor of a fixed syncopated accompaniment of dissonant chords on the off-beats that challenge the sense of the minor tonality. Even the final A minor chord in the last beat of the piece appears in an inversion.

In this piece, Stutschewsky did accept Engel’s suggestion to add a reprise. Engel praised this tune as “very good.”[1] In our recording the first exposition of the tune is slightly slower than the second one in order to allow the listener to appreciate the unusual harmonization.

___________________________

[1] Engel to Stutschewsky, ibid.