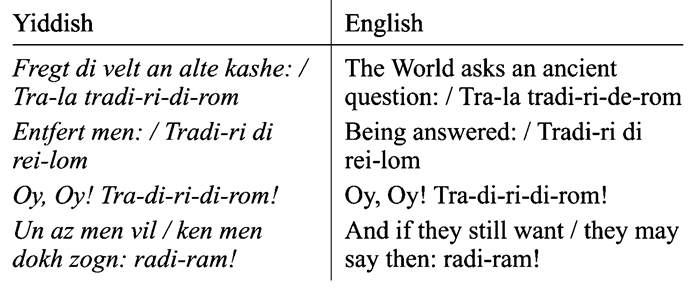

Die alte Kasche stands out in the Yiddish folksong corpus for its simplest and yet philosophical lyrics. The endless cycle of questioning is answered by the same set of non-sense syllables. This persistent questioning portrays a certain Eastern European Jewish stereotype.[1] Perhaps for this reason, Die alte Kasche appears in artistic arrangements by many composers. Among them are Arno Nadel (1906), Efraim Shkliar (191?), Joel Engel (1924), Alexander Schitomirsky (1912, no. 50) and Maurice Ravel (1915). In the case of Stutchewsky, the choice of this austere Yiddish song fits the overall minimalist aesthetics of this work.

Stutschewsky added the indication nicht eilen (don’t rush) to the title, which invites an Andante-like performance, correlating with most other renditions of the song, vocal and instrumental. The Yiddish intonation of the poem is ingrained in its tune. For example, the octave leap in bar 9 depicts the typical Yiddish sigh Oy! Furthermore, the descending melodic line of the folksong, from the words fregt di velt into an alte kasche, emphasizing the word alte is similar to the way the language is pronounced in speech. The rhythm and contour of the line Un az men vil / ken men doch zogn: radi-ram! also correlates with the spoken Yiddish. Stutschewsky underlined this moment of the song with the f dynamic that contrasts with the p of the rest of the song. The unaccompanied melody in bars 12-13 allows the soloist freedom to express in a textless gesture the content of the text. The three fermatas in bars 10, 11, 13, and in the last bar preceded with a ritenuto indication further emphasize the linguistic gesture of asking a question in a textless piece.

The tonality of Di alte Kasche is G freygish in both Stutschewsky and Schitomirsky’s arrangements. However, while Schitomirsky emphasized the conventional harmonization and reinforced the melodic line in the piano part, Stutschewsky moves away from the predictable from the very first chord. He challenges the listener with unexpected, charged chords. At the very beginning of the piece instead of the expected G major tonic chord, an F is played in the bass line creating a sharp dissonance with the G in the melody. Further in the same bar, the G major chord is avoided in favor of C minor. The last chord in bar 4 is half diminished on D – a sharp twitching surprise in a moment of expected release and closure. In bar 13, the poem’s climax, the listener is surprised with a lowered dominant seventh chord on D flat, instead of the expected dominant seventh chord on D. Also the beginning of the last line in bar 14 – the A flat in the bass against a B natural in the melody and a G flat in the piano’s right hand. Parallel to the opening, also the closing phrase does not begin with the anticipated G major, but with another dissonant chord to the melody – an A flat major seventh chord. Throughout this tune’s arrangement the pertinent dissonant chords color the poem with a modern, realistic flavor, adding depth and uneasiness to the alte kasche. On this tune Engel wrote: “Very good. One of the best numbers.”[2]

______________________________________

[1] This brings to mind the famous saying: “ - Farvos entfert a Yid a frage mit a frage? - Farvos nisht?” [ - Why does a Jew answer a question with a question? - Why not?].

[2] Engel to Stutschewsky, ibid.