נָכוֹן לִבּוֹ אִישׁ הוּא יָרֵא כָּל נְתִיבוֹ מִצְוַת בּוֹרֵא

נֶאֱמַר בּוֹ כָּתוּב אַשְׁרֵי כָּל חוֹסֵי בוֹ אַשְׁרֵי שׁוֹמְרֵי

הַרְאֵה נִסָּן, בְּיֶרַח נִיסָן, הָרֵם נִסָּן, דָּר מְעוֹנִי

עַם קְדוֹשִׁים נֶאֱמָן אוֹרָן הַזְרַח קוֹנִי

The piyyut Nahôn libbo by Rabbi Nissim Mazliah of Baghdad (end of the eighteen century to beginning of the nineteenth century) celebrates the Hebrew month of Nissan, the month associated with the holiday of Passover (see Shiloah 1983). Its traditional religious imagery could be read through the lenses of the modern national awakening of the Jews through the piyyut’s meta-subjects: the believer’s merits, individual and communal redemption and the notion of kibbutz galuyot, i.e. the ingathering of the exiled in the Promised Land.

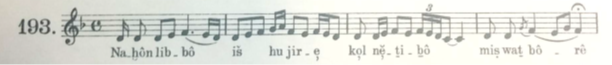

The inclusion of this Iraqi Jewish tune adapted from Idelsohn’s Thesaurus of Hebrew Oriental Music (1923b: 140, no. 193) is an unexpected turn after four consecutive Eastern-European folk tunes. Including such a piece within a European work for the concert stage is an avant-garde idea in itself, and a remarkable one for that time.

The groundbreaking ethnographic research of Idelsohn became an inspirational repository of “authentic” Jewish tunes for modern Jewish composers following their publication and Stutchewsky was no exception to this practice. Moreover, some of Idelsohn’s ideas related to the antiquity of the music of the Yemenite and Babylonian Jews were echoed in Stutschewsky’s writings (1935 and 1946) that also endorse the Zionist leanings of the famed musicologist.

Nahôn libbo opens the album’s middle sub-section, which seems to address the subject of belief through various religious and philosophical themed folksongs.[1] Nahôn libbo reflects a fundamental aspect of Jewish religious belief, the deep trust in God’s guidance. Not by chance, it is followed by the famous philosophical Yiddish folksong Die alte Kasche (no. 6) that appears to subvert this deep faith by raising an existential question that has no answer. This eternal enigma is then countered by two reassuring Hassidic nigunim:

number 7, Lied ohne Worte and number 8, A nigun on a soff that complete the middle sub-section of the work.

Idelsohn 1923b, no. 193

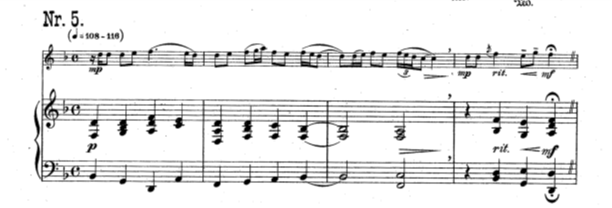

Nahôn libbo is hujire arranged by Stutschewsky:

Stutschewsky emphasizes the contrast between the Eastern European and the Iraqi musical worlds by means of two widely separated keys, F sharp minor and D Dorian F, slow versus fast tempo and symmetric versus asymmetric rhythms. Stutschewsky kept the mode, melodic contour, rhythm and fermatas as in Idelsohn’s source, apart from small additions: sixteen note rest (bar 1), tied notes (bars 3-4, 7-8), dynamics, ritenutos, and caesura indications. The accompaniment is an attempt to find a harmonic progression that will abide by the non-total modality of the melody. The somewhat naïve attempt to avoid clear tonal connotations in order to express “otherness” is found in the use of subdominant and the median chords. This strategy is clear in the different harmonization of the identical endings of the first two phrases.

Engel commented somewhat critically on this number that “places like bar 1 and especially 5 would sound well with cello, but with violin – thin. Here, I would suggest rather another line in the piano, even just doubling the violin, but an octave lower. In general, I see that in this regard you are very sparse. I don’t understand, why?”[2] Again we see in this piece Stutchewsky’s basic principle of designing accompaniments that will not interfere with the melody, but just punctuate it. The rather static, choral-like piano part indeed leaves the space open to the ornamented Iraqi Jewish melody.

_____________________________________

[1] Perhaps inspired by the song category titled Religiös-mystisches Lied in Kisselhoff 1913, a publication found in Stutschewsky’s library.

[2] Engel to Stutschewsky, July 20, 1924. Stutschewksy archive 3/2/1: 174/4.