Italy, Roman Tradition. Recorder: Leo Levy, performer: Guido Heller. Rome, Italy, 1953. From the JMRC CD, Italian Jewish Musical Traditions from the Leo Levi Collection (1954-1961).

Shofet Kol Ha'aretz

The piyyut Shofet kol ha’aretz (‘Judge of all earth’) is a center piece of the morning service for Rosh Hashanah in the Sephardic liturgy and appears also in the Yemenite rite where it has been found since at least the early eighteenth century (see, manuscript Berlin - Staatsbibliothek [Preussischer Kulturbesitz] Oct. 3321). While its prominence in the Sephardic and Yemenite rites is maintained to this day through performance, its presence in the Ashkenazi rite is obscured due to the general abandonment of its practice in the liturgy. For this reason, twentieth century scholars, as the present writer, tended to assume that Shofet kol ha’aretz is a Sephardic poem that found its way into the Ashkenazi rite. As the High Holy Days season arrives, we dedicate the Song of the Month to some rare recordings of the Ashkenazi melodies for this piyyut that were published by our website many years ago. It is worth returning to them now in a revised and updated version that incorporates unanticipated new findings. These findings show to what extent the availability of digital resources have enhanced the study of the Jewish liturgy helping us to make more accurate assessments and amend previous assumptions.

Shofet kol ha’aretz belongs to the medieval poetic Hebrew genre called pizmon that is characterized by a returning refrain at the end of each of the stanza of the poem. The poem consists of five stanzas. A sixth stanza was added later, apparently in Yemen, and is not included in many printed versions; even the fifth stanza is not included in Ashkenazi versions. Each stanza consists of four lines in the rhyme pattern AAAX, BBBxX, CCCxX, etc., whereas X, the last line of the opening stanza, is the refrain (same words and music are repeated) and x, the last line of the rest of the stanzas, is the “harbinger” of the refrain, always ending with the word “tamid” (a reference to the perpetual sacrifice in the Temple in Jerusalem) that corresponds to the last word of the refrain. The refrain (from Numbers 28, 23), recalls the close association between Temple sacrifices and synagogue prayers. Since the loss of the Temple, prayer has fulfilled the function of sacrifice.

The name of the author of Shofet kol ha’aretz, Salomon, surfaces from the acrostic – Shlomo hazaq ve’ematz – and for this reason the authorship of the poem is usually attributed to Salomon Ibn Gabirol (c. 1021-1058, Andalusia). However, scholars such as Leopold Zunz, have also suggested another possible author: Salomon bar Abun the young, (late twelfth century, of French origin but active in the Iberian Peninsula; see Abrahams 1920). Even the name of Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Itzhak) appears as possible author. All these attributions are still contingent although new manuscript evidence shows that the attribution to Bar Abun is not at all farfetched.

Indeed the present-day availability of medieval manuscripts of Hebrew liturgical orders allows for a fundamental revision of the origins and practice of the pizmon Shofet kol ha’aretz. Thanks to the superb catalogue of the Institute of Microfilmed Hebrew Manuscripts (hereby: IMHM) at the National Library of Israel, we can reconstruct with a certain degree of accuracy how Jewish liturgical practices evolved prior to the invention of the printing press.

Among the novelties that emerged in the past decade or two are the discoveries of the “Italian Genizah,” confiscated folios of Hebrew manuscripts that were used by Christians for the binding of other books. These fragments cast new light on the presence of Shofet kol ha’aretz in Ashkenaz in the medieval period, apparently predating its use among Sephardic Jews. Manuscript 85 of the Archivio Storico Comunale of Modena contains fragments from an order of Selihot of the Ashkenazi Jews in Italy, dated to the 13th or 14th century (IMHM, PH 6651). Fragment 1 of this manuscript includes the beginning stanzas of Shofet kol ha’aretz. Another much more complete manuscript from the 13th century containing our poem (twice) is the French (Western Ashkenazi) order of prayers for the High Holy Days, at the Biblioteca Palatina in Parma, Cod. Parm. 2889 (De Rossi Catalogue 855; IMHM, F 13782).

Even more interesting is the mention of the melody of Shofet kol ha’aretz in the manuscript of the National Library in Prague, Narodni Knihovna v Praze VI Ea 2 (IMHM, F 47395) that is also dated to the thirteen century. This is an order of prayers for the entire year according to the tradition of Worms. Before the poem “Melitz yosher ya’amod, tehillato yesaper” (fol. 15 in the manuscript) appears the superscription “Be-niggun [according to the melody of] Shofet kol ha’aretz.” This is the earliest mention of the music of our poem, and obviously it indicates that in the circle of the (Western Ashkenazi) users of this manuscript there was an awareness that a traditional melody for Shofet kol ha’aretz was already in place and could be transferred to the singing of other texts.

The thirteen to fourteen century Ashkenazi Mahzor at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy in St. Petersburg D 101 (F 69720) includes Shofet kol ha’aretz for the second day of Rosh Hashanah, after Avinu malkenu (fol. 340b), unlike other Ashkenazi sources that place the poem on the first day of Selihot or on Yom Kippur. What is even more important from an historical perspective is that this Western Ashkenazi source apparently moved eastwards, as it contains many Eastern Ashkenazi texts added later in its margins. Through manuscripts such as this we can see the move of Western Ashkenazi liturgical poems such as Shofet kol ha’aretz to Eastern Europe.

When Shofet kol ha’aretz appeared in printed prayers books of the sixteenth century, its pedigree in the liturgical practice of Western Ashkenaz was therefore ancient. Among the earliest printed versions of our poem are Selihot mi-kol Hashanah (Venice, 1548), the Mahzor for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur with a commentary by Rabbi Moshe Cordovero printed in Constantinople in 1576 and Tahanunim ve-Selihot ke-minhag italiyani, Venice, 1587. This last appearance in the non-Ashkenazi Italian rite is also attested in several medieval manuscripts of the Roman Jewish rite available at the IMHM catalogue.

The persistence of our poem in the heart of the German soil and its presence further East, in Poland, is understandable in light of its medieval pedigree. It appears for example in the Selihot according to the order and tradition of the Holy Congregation of Fiorda (Furth) that our forefathers told us that they received as an order according to the order and tradition of the community of Niren Burg that they had from times immemorial, Sulzbach, 1757. This edition is interesting because Shofet kol ha’aretz appears on p. 85, as part of the Selihot for Yotzer of Yom Kippur with interpolations of verses in between each of the stanzas of our poem.

More information regarding the performance of our piyyut appears in the Mahzor mi-kol Hashanah Minhag Polin, Altona, 1826, p. 326. This prayer book includes an appendix titled ‘Minhagim (“Customs”) written by the Gaon Our Master Rabbi Isaac Tyrna with additions… written by the Gaon Our Master Rabbi Abraham Kloyzner”. This is a reference to Rabbi Isaac Tyrnau, an Austrian rabbi active in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century in Vienna and its vicinities who is most famous for his Sefer ha-minhagim (Book of Customs) that was printed for the first time in Venice in 1566 and then reprinted in more than one hundred editions. Rabbi Kloyzner was one of his mentors. We mention this quotation from this secondary source because its printing as an appendix to a prayer book shows how much these early medieval customs were still reproduced among the Jewish intelligentsia in Eastern Europe in the early nineteenth century.

The relevant passage from Rabbi Tyrnau’s medieval compendium reads: “On the eve of Rosh Hashanah, 29th of Elul, we rise early before daybreak [go to synagogue], recite the petihah (“opening”) ‘Nora ba-eliyonim,’ the thirteen selihot (against the Thirteen Attributes of God), then open the Ark and say the pizmon ‘Shofet kol ha’aretz’ and one should not close the Ark after ending Shofet…” In the same prayer book of 1826, on p. 287 in the morning prayers of Yom Kippur appears a note saying “Shofet kol ha’aretz, you will find it with commentaries in the selihot of Rosh Hashanah.” This means that the poem was recited on both Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

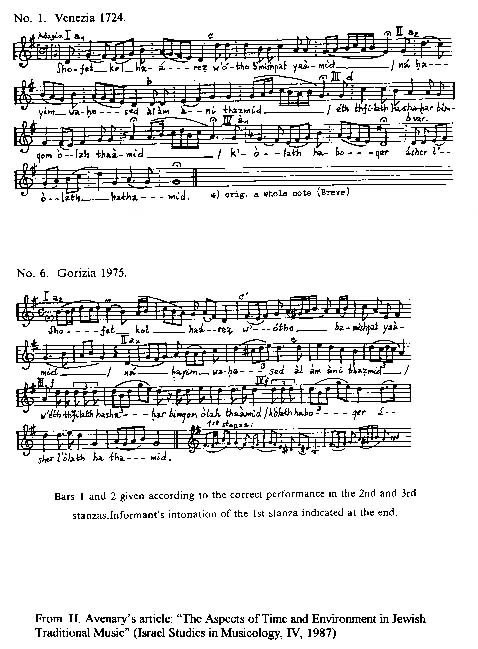

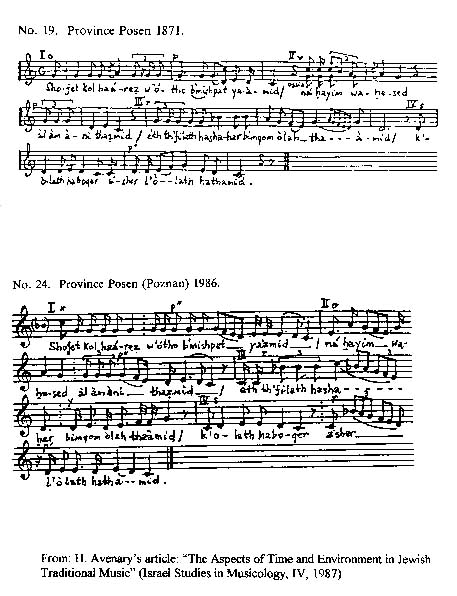

In short, in the Ashkenazi order of prayers, first in the West and then in the East, Shofet kol ha’aretz appears as an epilogue (or, in certain rites, a prologue) to the penitential hymns (selihot) sung preceding and during the High Holidays. In a thought-provoking article on the music of Shofet kol ha’aretz in Ashkenaz, our teacher of blessed memory Prof. Hanoch Avenary (1908-1994) discussed twenty-four variants of the melody for this piyyut. Avenary classifies these variants into two main branches and traces their development against the background of the various Ashkenazi musical cultures.

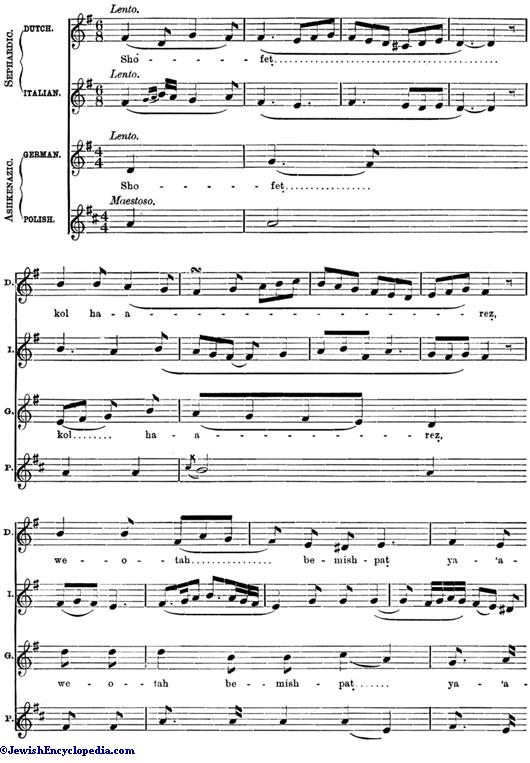

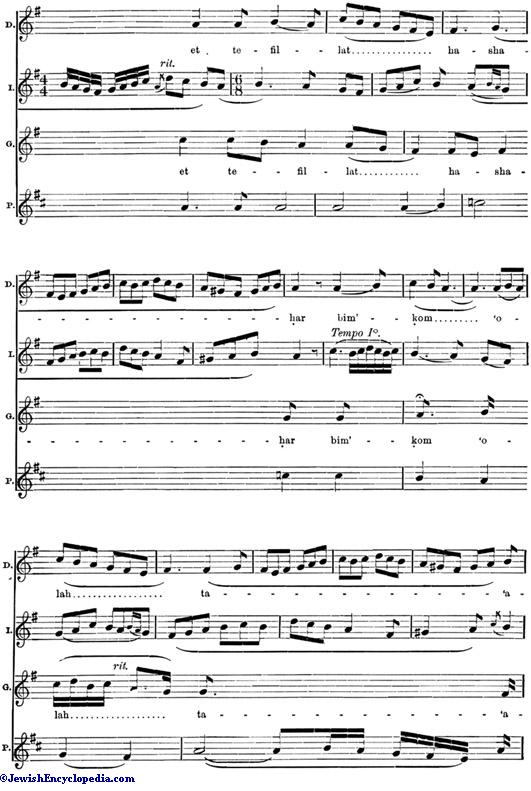

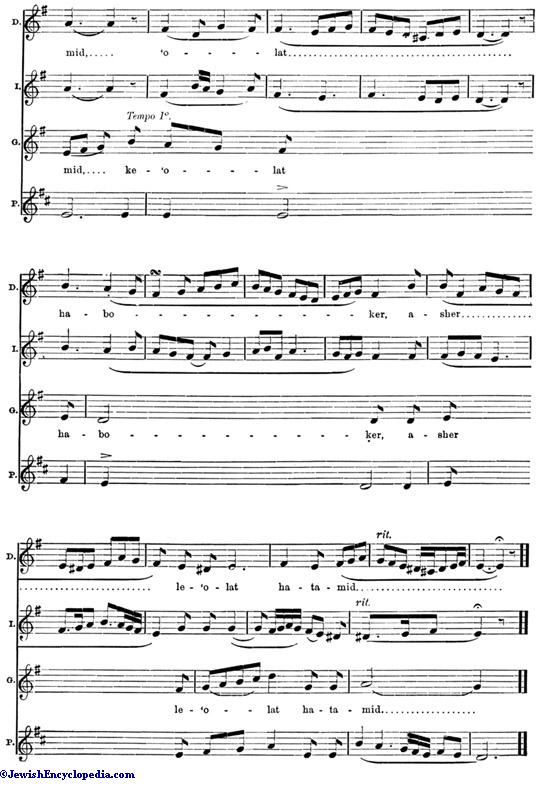

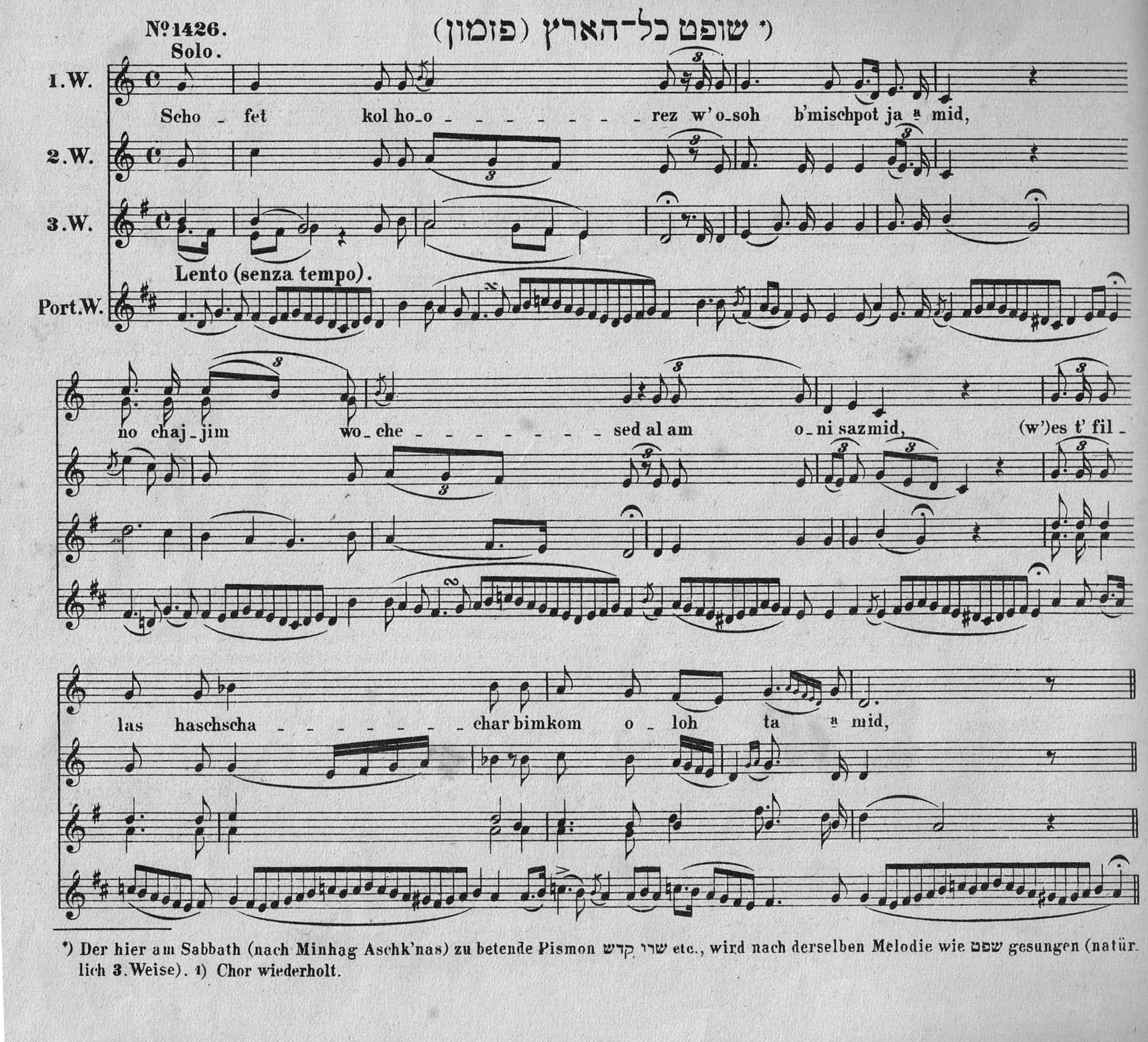

The Ashkenazi tradition of this pizmon comprises what Avenary calls the “common” Ashkenazi melody (seventeen versions, the earliest one already documented in 1724 and 1733) found in South and West Germany, West of the Rhine river (See Image no. 1) and in North Italy (see image no. 2), and an “alternative” tune (seven variants) preferred by the communities of the “Polish rite” (East of the Elbe and Moldau river) (see image no.3). A melodic structure of four phrases, corresponding to the four lines of the poem’s stanzas is shared by all the variants. Each phrase is composed of two motifs which subdivide the long poetic verse of thirteen or more syllables.

Avenary is able to establish the characteristics that unite all the variants of the three sub-types of the “common” melody into one type. He also points out the features that separate these three sub-types. Avenary shows the pentatonic foundations of the melody and its relationship to some features of the Ashkenazi Torah chant. Placing the three sub-types of the “common” Ashkenazi melody against their historical background, Avenary concludes that each of the three regions of Western Ashkenaz consolidated their own variants of the Shofet melody in a more or less individual manner. While variants of the Center and the West are rather close to each other, the Southern branch in Italy had disengaged itself even before 1724 (the year the publication of the melody by Benedetto Marcello in his Psalms; see Seroussi 2002) from the transalpine tradition and had embraced the music aesthetics of the surrounding culture. The lyric quality of the tune (Avenary’s term here is “balanced course of Southern melody” by with he probably meant Italian melody), with its melodious and embellished ductus, became completely dissociated from the old-fashioned pentatonics with their reminiscences of Biblical chant.

The “alternative” Eastern European melody of Shofet kol ha’arez bears the unmistakable stamp of the Eastern Ashkenazi style of hazzanut. It is not only the expressivity and the strong accent placed on words of emotional and imaginative capacity that are characteristic of this style. The melody itself is not based on a “universal musical language” (Avenary’s term) like pentatonics, but uses a strongly profiled Jewish prayer mode whose foremost characteristic is a stock of idiomatic motifs whose appearance indicates to the initiated listener the liturgical context of its performance.

In spite of their different modality, the two melodies, the “common” or Western and the “alternative” or Eastern, have some common features: interesting motivic relationships can be observed of which the most obvious one is the final cadence which is shared by most of the “alternative” variants and by all of the “common” versions, except the Southern (Italian) one. This cadence is a quotation of the motifs used for the closing masoretic accents of the Pentateuch verses as chanted on the High Holidays. The use of a prominent motif of Biblical chant as the final cadence of most Shofet versions can be interpreted in two ways. First, the last verse of each stanza is always a quotation from the Bible, and there are precedents for the connection of Bible texts with Biblical chant. Furthermore, this topical motif of the High Holidays forms a musical link between the festival season and Shofet kol ha’aretz. This kind of relation between a song and its liturgical context is frequent and is almost a precondition for the acceptance of a melody into the traditional Ashkenazi repertoire.

Up to here are the observations by Hanoch Avenary. Of course his terminology is a bit uncomfortable to post-modern ears. Categories of authentic and ethnic musical purity (such as “universality” of pentatonicism versus “a strongly profiled Jewish prayer mode”) are freely deployed in his analysis.

Preceding Avenary in the study of Shofet kol ha’aretz was the Reverend Francis L. Cohen (1862-1934) (Cohen, 1906) and a comparison between them is instructing. The scholarship of Cohen (who was also the first Jewish chaplain of the British Army) is sometimes questionable but not at all without value. We quote here some of his observations with editorial notes by us in brackets because they are worthwhile to those interested on the historiography of Jewish music. Cohen’s style is characterized by associations of ideas and by intertwining Sephardic and Ashkenazi liturgical traditions into a single. In this sense, he reflects his upbringing in the Victorian British Jewish community in which the lines separating Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jewish liturgies were blurred in favor of an “Imperial British minhag”. Notice that Cohen already proposed at this early stage that the Spanish-Dutch, i.e. Western Sephardic, melody is probably the “original” one. He also heralds some of Avenary’s points.

The hymn [Shofet kol ha’aretz] and its traditional tune are alike given places of honor in both the northern and southern rituals [i.e. Ashkenazi and Sephardic rituals]. With the Ashkenazim, who utilize only the first five [or four] verses [stanzas], the hymn is the chief poem [!] in the Seliḥot for the day preceding New-Year, and again in those of the morning service for the Day of Atonement. On both occasions it is differentiated from all other seliḥot by the special declamation, to the solemn penitential melody (see Ashre ha-'Am) of the applicable Scriptural texts which immediately precede it. In the German order of seliḥot, when another hymn is substituted on Sabbath morning, such hymn is still sung to the tune of 'Shofeṭ.' With the Sephardim it precedes the 'Nishmat' in the morning service for New-Year.

Its melody is chanted in the Spanish rituals, to different passages of solemn importance in the penitential services—chiefly such as are recited by the ḥazzan alone—almost as often as the frequently-repeated melody of 'Lema'ankha' (for which see [Cohen’s article on] Adonai Beḳol Shofar [in the Jewish Encyclopedia]) is sung to the congregational hymns. It [the melody of Shofet] is thus used for the special reshut 'Oḥilah [la-el],' which ushers in the [Day of] Atonement additional service [Mussaf], and in some lines of tradition [i.e. Sephardic traditions] for the [Seder] 'Abodah as well. On New-Year it is similarly used to precede the additional service; and, in Italy, for 'Alenu' as well as universally for the first utterance of the thrice-repeated prayer ['Ha-Yom Harat 'Olam'; on the use of the melody of Shofet kol ha’aretz for this prayer, see Seroussi 1999] which follows the sounding of the Shofar.

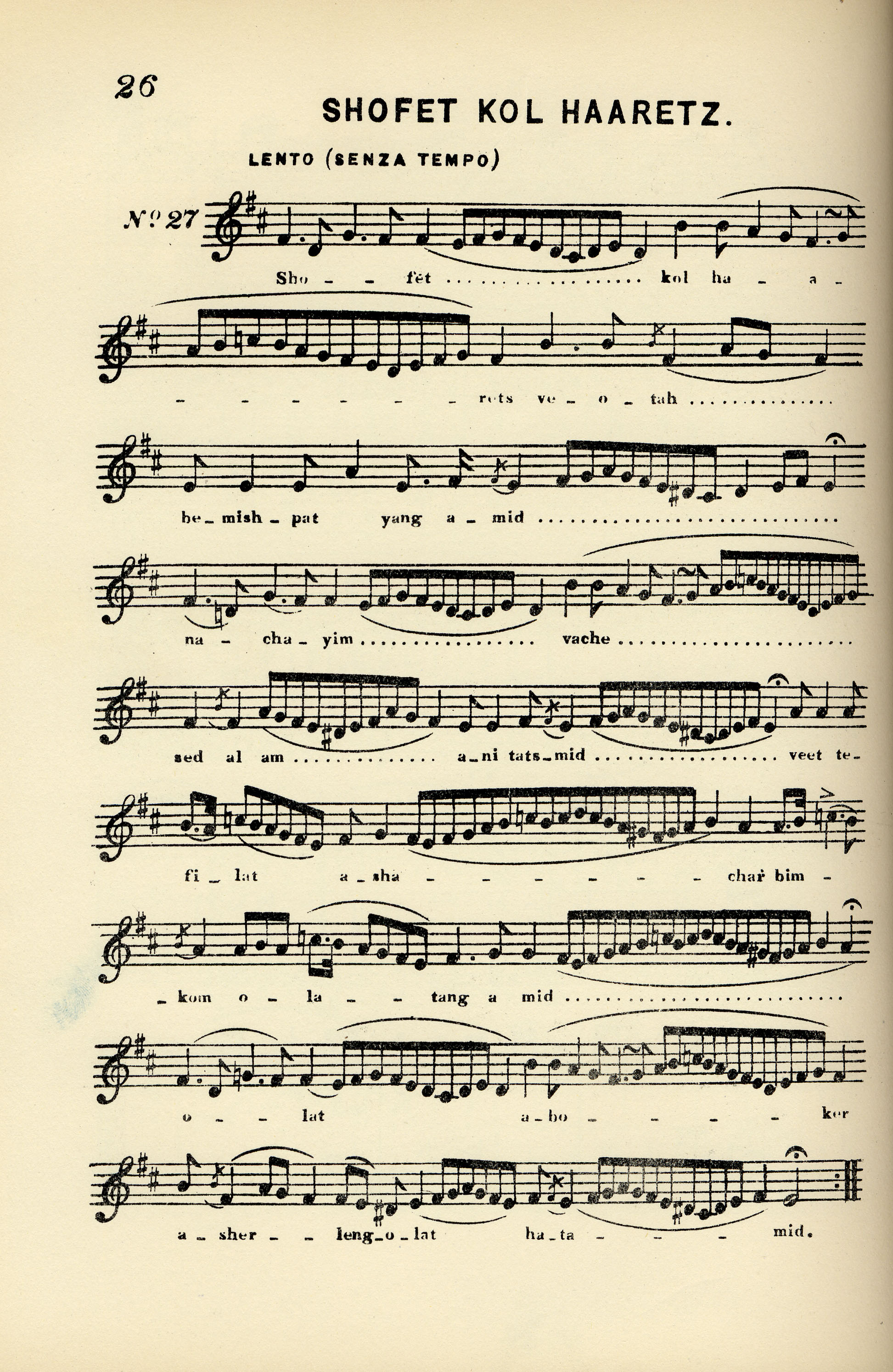

Thus, alike by Ashkenazim and by Sephardim, the ancient melody for this hymn is regarded as one of the most important associated with the Ten Days of Repentance. It exists in several variants—an evidence merely of its age. The Ashkenazic and Sephardic forms differ very considerably in detail, betraying respectively a distinct German or Arab influence, with a corresponding modification of structure. Each usage, again, differs within itself according to local tradition. The variants of Amsterdam ([David Aharon] De Sola [and Emmanuel Aguilar], “Sacred Melodies” [Ancient Melodies of the Spanish and Portuguese Liturgy] No. 27, London, 1857) and of Leghorn [Livorno] ([Federico] Consolo, “Libro dei Canti d'Israele,” No. 308, Florence, 1892) are by no means in agreement in detail. Four forms [of the melody], two Polish and two German, are presented by [Abraham] Baer ('Ba'al Tefillah,' [Oder, Der practische Vorbeter: Vollständige Sammlung der gottesdienstlichen Gesänge und Recitative der Israeliten nach polnischen, deutschen (aschk'nasischen) und portugiesischen (sephardischen): Weisen nebst allen den Gottesdienst betreffenden rituellen Vorschriften und Gebräuchen], No. 1426, [2nd. Ed.], Frankfort-on-the-Main, 1883). The link [between the Sephardic and Ashkenazi traditions] is supplied by the Italian tradition, which utilizes the characteristic Sephardic form for the initial verse, and approximates closely to the Ashkenazic in those that follow. Benedetto Marcello in his 'Parafrasi Sopra li Salmi,' published between 1724 and 1727, uses as a theme for Ps. xxi. (Vulgate numbering = Ps. xx. in the Hebrew) another variant, which, however, is close to one of the German forms of the melody [see Seroussi 2002]. Four of the most characteristic variants—Spanish-Dutch (probably the original [sic]), Italian, German (that used by Marcello), and Polish—are given in the accompanying transcription [see images 4, 5, 6, 7; notice that in the first example copied from De Sola-Aguilar, Cohen has “metrified” the melody into 6/8; in the original transcription there are no bar lines, attesting for the flexible rhythm and lack of fixed beat of this melody, a feature kept in all oral variants].

The research infrastructure laid by Avenary and Francis L. Cohen is a solid beginning towards deeper inquiries into the music of this ancient poem. Considering the recorded resources now available to researchers, such an inquiry can render further insights that could not be envisioned by these two pioneers of Jewish musicology.

Text and translation of Shofet kol ha’aretz

שׁוֹפֵט כָּל הָאָרֶץ וְאוֹתָהּ בְּמִשְׁפָּט יַעֲמִיד

נָא חַיִּים וָחֶסֶד עַל עַם עָנִי תַּצְמִיד

וְאֶת תְּפִלַּת הַשַּׁחַר בִּמְקוֹם עוֹלָה תַּעֲמִיד

עוֹלַת הַבֹּקֶר אֲשֶׁר לְעוֹלַת הַתָּמִיד

לוֹבֵשׁ צְדָקָה וּמַעֲטֶה לְךָ לְבַד הַיִּתְרוֹן

אִם אֵין בָּנוּ מַעֲשִׂים זָכְרָה יְשֵׁנֵי חֶבְרוֹן

וְהֵם יַעֲלוּ לְזִכָּרוֹן לִפְנֵי ה' תָּמִיד

עוֹלַת הַבֹּקֶר אֲשֶׁר לְעוֹלַת הַתָּמִיד

מַטֵּה כְּלַפֵּי חֶסֶד לְהַטּוֹת אִישׁ לִתְחִיָּה

עַמְּךָ הַטֵּה לְחֶסֶד גְּמָל נָא עָלָיו וְחָיָה

כְּתֹב תָּו חַיִּים וְהָיָה עַל מִצְחוֹ תָּמִיד

עוֹלַת הַבֹּקֶר אֲשֶׁר לְעוֹלַת הַתָּמִיד

הֵיטִיבָה בִרְצוֹנְךָ אֶת צִיּוֹן עִיר קֳדָשַׁי

וְנָתַתָּ יָד וָשֵׁם בְּבֵיתְךָ לִמְקֻדָּשַׁי

עֲרִיכַת נֵר לְבֶן יִשַׁי לְהַעֲלוֹת נֵר תָּמִיד

עוֹלַת הַבֹּקֶר אֲשֶׁר לְעוֹלַת הַתָּמִיד

חִזְקוּ וְיַאֲמֵץ לְבַבְכֶם עַמִּי בְּאֵל וּמָעֻזּוֹ

עֵדֹתָיו כִּי תִנְצְרוּ גַּם אֶת זוֹ לְעֻמַּת זוֹ

הוּא יָגֵן עֲלֵיכֶם וְיִזְכֹּר רַחֵם בְּרָגְזוֹ

דִּרְשׁוּ ה' וְעֻזּוֹ בַּקְשׁוּ פָנָיו תָּמִיד

עוֹלַת הַבֹּקֶר אֲשֶׁר לְעוֹלַת הַתָּמִיד

Additional stanza (not in the Ashkenazi versions)

בְּנֵי עֲבָדֶיךָ הַיּוֹם לְמִקְדָּשְׁךָ יֶאֱתָיוּ

וְצוֹעֲקִים בְּפִיהֶם וּלְחַיֵּיהֶם [וּבִלְבָבָם] יִבְעָיוּ

זוֹכְרִים צִדְקוֹת אֲבוֹתָם ה' עֲלֵיהֶם יִחְיוּ

אוֹתָם תִּזְכֹּר וְהָיוּ נֶגֶד ה' תָּמִיד

עוֹלַת הַבֹּקֶר אֲשֶׁר לְעוֹלַת הַתָּמִיד

Translation by Mrs. Alice Lucas (in Abrahams 1920)

Judge of the earth, who wilt arraign

The nations at thy judgment seat,

With life and favor bless again

Thy people prostrate at thy feet.

And mayest Thou our morning prayer

Receive, O Lord, as though it were

The offering that was wont to be

Brought day by day continually.

Thou who art clothed with righteousness,

Supreme, exalted over all

How oft soever we transgress,

Do Thou with pardoning love recall

Those who in Hebron sleep: and let

Their memory live before Thee yet,

Even as the offering unto Thee

Offered of old continually.

O Thou, whose mercy faileth not,

To us Thy heavenly grace accord;

Deal kindly with Thy people's lot,

And grant them life, our King and Lord.

Let Thou the mark of life appear

Upon their brow from year to year,

As when were daily wont to be

The offerings brought continually.

Restore to Zion once again

Thy favor and the ancient might

And glory of her sacred fane,

And let the son of Jesse's light

Be set on high, to shine always,

Far shedding its perpetual rays,

Even as of old were wont to be

The offerings brought continually.

Trust in God's strength, and be ye strong,

My people, and His law obey,

Then will He pardon sin and wrong,

Then mercy will his wrath outweigh;

Seek ye His presence, and implore

His countenance for evermore.

Then shall your prayers accepted be

As offerings brought continually.

References quoted

Israel Abrahams, “A piyyut by Bar Abun,” By Paths in Hebraic Bookland. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1920, pp. 97-101. Includes the translation of the poem by Mrs. Alice Lucas, a distinguished British Hebraist, whose full version was published by Abrahams for the first time and is reproduced below. Another female Hebrew Hebraist, Nina Salaman, included a translation of the poem in the famous Routledge Machzor (1909, Day of Atonement, Morning Service, p. 86).

Hanoch Avenary, “The Aspects of Time and Environment in Jewish Traditional Music,” Israel Studies in Musicology 4 (1987): 93-123.

Francis L. Cohen, “Shofet Kol Ha-aretz” (“Judge of all the University”), Jewish Encyclopedia, 1906, vol. 11, p. 306.

Edwin Seroussi. “Toward a history of Jewish oral traditions: The singing of the prayer ‘Hayom harat olam’ in Sephardi synagogues.” Rivista Internazionale di Musica Sacra 20 (1999): 151-174.

Edwin Seroussi, “In Search of Jewish Musical Antiquity in the 18th-century Venetian Ghetto: Reconsidering the Hebrew Melodies in Benedetto Marcello’s Estro Poetico-Armonico,” The Jewish Quarterly Review 93/1-2 (2002): 149-200.

Sound Examples

Sephardic tradition. Performer: Aaron Najari. NSA CD7182.

Transcription of Shofet kol haaretz from De Sola and Aguilar (1857). Its general contour reminds Najari's recorded rendition. Compare this transcription with its copy by Francis L. Cohen.