1995

Qad Zawajunī - Here I Was Wed

Background

Qad Zawajunī is a form of 'play song” or singing game commonly performed among the Jewish communities of central and southern Yemen. It is sung at the end of the bridal henna ceremony as part of the repertoire of Yemenite Jewish women singers. In Yemen, the separation of men and women was customary at day-to-day events as well as during events and ceremonies associated with the life cycle. However, the strictness of this gender-based segregation was variable depending on the level of religious observance in each specific community. For example, in central Yemen cities such as the capital Sana'a the separation of the sexes was more stringent, while in the villages there was more flexibility.

The richness of this female Jewish repertoire is manifested in the songs' themes, such as the internal spiritual world of the individual and one's relationship with God, themes that are attributed mainly to Jewish men's songs (including liturgical and para-liturgical music). The repertoire also deals with themes that reflect daily life, as well as material and corporeal subjects. [1]The music in these songs reflects the feelings and state of the women within intimate settings; when they are alone, such as when they grind flour before dawn, or in private settings while completing daily chores, such as taking water from the well and collecting firewood. Additionally, the songs are connected to life-cycle ceremonies such as weddings, births, and deaths.[2] Jewish women in Yemen were not allowed to learn reading and writing, therefore their songs were transmitted orally.

The henna ceremony takes place before the wedding ceremony. It is part of the extensive series of Yemenite Jewish wedding rituals, whose number and length varies according to community.[3] For example in the south-eastern city of Rada'a, which once housed a considerable Jewish community, the wedding celebrations last a month, beginning with the Sabbath before the wedding. [4]

The henna ceremony is practiced by Jewish communities throughout the Middle East and North Africa and, as in the case of the Yemenite community, a particular song repertoire associated with this ceremony developed in each place. The Yemenite henna ceremony is still common today among the Yemenite communities of Israel, even though its cultural context and the functions that it upheld have changed because of the extreme transformation that the Yemenite Jews have undergone since their emigration to Israel. One example of the henna repertoire is the song ‘Abiadi Ana,’ which is still performed in Israel as part of the Moroccan Jewish henna ceremonies.

The timing of the ceremony itself, in which the bride is decorated in henna, a plant-derived dye used to temporary decorate her skin and especially the hands and feet, varies among the different Yemenite communities. [5]In general, the henna ceremony comes after the festive dressing of the bride in her traditional regalia. In some places such as Rada'a, in between these two ceremonies the bride is led to the mikve (ritual bath) or a local stream by her mother, sisters and the woman in charge of decorating her in henna (alshare'a in Arabic). At the bride's house, after the evening feast or light refreshments, the women and the share'a sing and dance while they decorate the bride's hands and feet with the henna paste. [6]

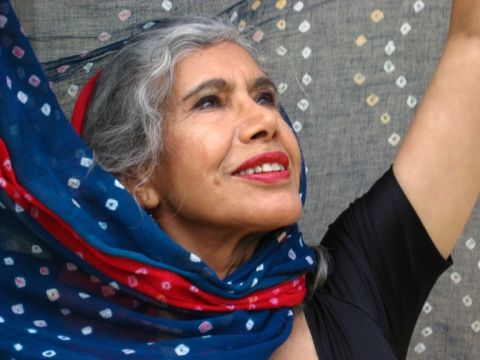

Leah Avraham

The performance of 'Qad Zawajunī' is by singer, dancer, artist and educator Leah Avraham in a style typical of central and southern Yemen. Avraham was born in 1943 in Gabzia, Yemen, a small village in the Al Hugariya district in south-west Yemen. Her mother Sham'a was a poet and professional mourner, who, as was customary at the time, took her daughter with her to events that she attended. The family arrived in Israel in 1949 as part of Operation Magic Carpet. During her professional career, Avraham was a member of the Inbal Dance Theatre, which among other projects created artistic pieces inspired by traditional Yemenite Jewish dances. She later went on to join the Batsheva Dance Company, which focuses on contemporary dance. At the same time, she also enjoyed a singing and acting career in Israel and abroad and she combined these different fields in her educational activities as well.

According to Avraham, the song repertoire of Yemenite Jewish women, which she collected over the years from her mother and other women, was the inspiration behind her work. Today she continues to perform across Israel works from the Yemenite Jewish male and female song and dance repertoires.

Qad Zawajunī in English translation, Arabic transliteration and Hebrew translation

|

הִנֵּה הִשִּׂיאוּני

הִנֵּה הִשִּׂיאוּני עלמה עלמה קשת לב, על גבי עצים היא העמיסה על ראשי חֵמֶת מים העיקה.

מי יִתֵּן והִשִּׂיאוּני עלמה בתה של אופה, פניה כסהר האירו ועיניה קרצו הבטיחו.

הִנֵּה הִשִּׂיאוּני עלמה מבנות שבטי, לב פלדה לבה וְנַפְשָׁהּ לא תֵּדַע שְָׂבְעָה.

מי יִתֵּן והִשִּׂיאוּני עלמה נערה מבנות חידאן, אתי תִּרְקֹד וְתִרְגַּש יפה היא ומתוקה מִדְּבַשׁ.

צָרֵי העין לעגו לי 'בשחורה חשקת'– כך אמרו, אכן עורה כִּשְׁחוֹר הָעֵנָב, כַּמוּשְׁק ביום שרב. |

Qad Zawajunī

Qad zawajunī bnaye qalbha qasī, Qad ḥammalatnī al-ḥaṭab walma – cala rasī

Law zawajunī bnaye bint al-khabbaza, Al-wajh zay al-qamar wal-cayn ghammaza,

Qad zawajunī bnaye min banat ahlī, Al-qalb zay al-ḥadīd wamaṭlūbha ghalī,

Law zawajunī bnaye min banat Ḥaydan, Turquṣ watifraḥ macak wakulha ḥalī

Qad cayrunī al-ḥusūd qalū cshiqt al-ssūd, Wal- ssūd – sūd al-cnab wal-misq fī al-ṣṣundūq. |

Here I Was Wed

Here I was wed to a young woman A hard-hearted young woman Who burdened my back with firewood And my head with a gourd of water

If only I was wed To a baker's daughter Whose face would shine like a crescent moon And her eyes winked and promised.

Here I was wed to a young woman a daughter of my tribe her heart was of steel and her soul could not be pleased.

If only I was wed to a young woman of Ḥaydan Who would dance with me and excite me She would be beautiful and as sweet as honey

The jealous mocked me 'you desire a black one' that's what they said It's true, her skin is as a black grape, like a musk on the hottest of days. |

The recorded performance of the song featured in this article (from Avraham's 1995 album Neve Midbar) freezes the song into a closed text that remains unchanged every time someone listens to it. However, I analyze the song as it would have been performed during a henna ceremony, i.e. as a live performance that cannot be precisely replicated because it varies from one performance to another.

“Qad Zawajunī” was traditionally performed at the conclusion of dances associated with the henna ceremony, when the young women would stay and celebrate until the small hours of the night. As is characteristic of women's singing at Jewish Yemenite wedding celebrations, this song is sung in a responsorial style. However, rather than having one soloist who is answered by the remaining singers, here the women take turns entering into the center of the dancers’ circle, singing one line while dancing and having the rest of the women respond to her by repeating the line that she sang. According to Avraham’s testimony, the number of women participating in the event dictates the length of the performance.

Folklore scholar Vered Madar mentions in her doctoral thesis that many scholars of folklore deal with the question of how carriers of folk culture remember texts that are transmitted orally. According to Madar, one of the creative mechanisms that allows for the remembrance of such texts is the use of fixed textual formulas of variable lengths. These formulas are used by the poet, or in this case, the women who participate in the celebrations, as a basis for actions that Madar calls 'creativity during performance.' [7] Examples of these textual formulas can be found in “Qad Zawajunī.” For example, in the opening hemistich of each stanza we have the same wording: 'Qad zawajunī bnaye' (Here I was wed) and 'Law zawajunī bnaye,' (If only I was wed). Each of these two formulas allow each woman, in turn, to create a text to follow these opening lines as she sees fit.

The present version of the song is divided into five stanzas of two rhyming lines (except for the last two stanzas) with each line consisting of two hemistiches. Musically, each textual line is accompanied by a melodic phrase. This pattern creates a binary musical structure of two phrases which alternate in an ABAB form. Rhythmically, the song is in duple meter and it mostly has simple and symmetrical rhythmic structures, which include quarter notes, pairs of eighth notes and pairs or groups of four sixteenth notes. The text-music relation in this song is primarily syllabic with a few ornamentations.[8]

According to Avraham, the separation between men and women during events such as the henna ceremony created a space where women could freely express themselves on a number of subjects. These themes include the difficulties of day-to-day life and even criticism of their social status in their communities: 'At their parties they [the Yemenite women] are on their own. They can speak candidly about men, complain about them, but in this way it kind of makes it a bit of a joke. What are they doing? In the text they are turning the man into a kind of woman. There is no such thing as zawajunī, that the man would say 'I was wed to…' On the contrary, the woman is wed to the man. […] She complains about her difficult life in the opposite manner. That is to say, she says 'let's see you [the man] deal with way we have to put up with.’'

Avraham suggests that the song's narrator is presented as someone who wants to 'enjoy the best of all worlds' without putting in any effort. He complains that his hard-hearted wife makes him do all of the difficult day-to-day tasks such as collecting firewood and drawing water from the well, while he dreams of being married to a baker's daughter, who is as beautiful as a crescent moon and is sexually alluring – 'her eyes winked and promised.'

The responsorial performance of the songs helps create that same freedom that Avraham discusses, or what can be called a space of solidarity in which the female voice is permitted to be heard. In this context, Madar equates the repetitions of the words of the song by the listeners/participants as a type of “echo” which creates 'a communal space in which individuals are in contact and are responded to.' [9] She calls this space 'the female voice community.'[10] This sense of community is reinforced because the song is not the product of one poet but rather is 'quilted' together by the women participating in the event.

As Avraham states, the protesting side of the song is presented indirectly and somewhat humorously, by subverting the gendered roles that are traditionally attributed to women and projecting them onto a man. The narrator's complaints about his bitter fate are used by the women to critique the patriarchal society's expectations from them: that they carry out all of the difficult chores that are mentioned in the text and that they happily accept their place and role in society. This theme is also expressed through the lyrics, which are structured with a recurring contrast between reality and fantasy in the two words that open each stanza in alternation:“Qad” (here) compared to “Law” (If only).

An additional theme, found in the recording’s fourth verse, is the power dynamics between urban and rural Jewish women in Yemen. In accordance to the rigid religious lifestyle of the cities, the urban women were seen as more prudish and conservative in comparison to women in rural areas. According to Avraham, feminine beauty ideals also changed in accordance to this division: in cities like Sana'a the women had lighter skin, which was considered to be more beautiful,[11] while in the villages the women's skin was darker, a feature considered to be sign of beauty in turn. Avraham assumes that this stanza about the women of Haydan (north-west Yemen) was originally sung by a woman from this village, since it is complimentary to that area and to rural women in general. The comparative aspect of the song emphasizes this theme as well; the urban woman symbolizes the stark reality to which the man finds himself, while the rural woman symbolizes his fantasies.

Avraham's analysis contradicts aspects of the female protest embedded in this piece. The song expresses the women's desire to be the object of men's fantasies while praising characteristics such as light-mindedness and beauty as traits that need to be attained. It could be that this contradiction reflects an inner conflict in the women's identity, which is connected to their role and place in society. The mere fact that these issues are a topic of song proves the power of music to create an alternative, feminine discourse that subverts the order of the patriarchal society. At the same time, as Madar suggests, the performances of the song 'do not aspire to change the social order, but rather provide a space to express the stances and viewpoints of the women themselves.' [12]

[1] See Madar, 2011, 7.

[2] Ibid, 34; see also Nahshon 2007, 48.

[3] See Shay,1985.

[4] See Ratzhabi, 1963, 52.

[5] For research on the wedding customs of the Yemenite Jewish women see Ratzhabi 1955 and Spector 1960 for San’a; Ratzhabi 1963 and Klein 1980 for Rada’a and Shay 1985 and 1996 for Habban

[6] See Ratzhabi 1955, 330: Ratzhabi 1963, 52-53

[7] See Madar 2011, 55-57

[8] This analysis is inspired by Rachel Hoffman's doctorate who, along with Professor Edwin Seroussi, was the last person to point to criteria for the analysis of Yemenite Women's song sung at henna ceremonies in Israel. See Hoffman 2011, 109-187.

[9] See Madar 2011, 52

[10] Ibid, 53

[11] This opinion is also supported by Ratzabi (see 1974, etc.) in an article which deals with the love poetry repertoire found among the women of Sana'a. In these songs, he said, the face of the beloved 'shines like the moon, with skin clear and white, and from this comes the saying 'the daughter of porcelain.''

[12] See Madar 2011, 8,244

References quoted

Madar, Vered. 'Women's Songs from Yemen for Maternity and Mourning the Dead: Text, Body and Voice,' Doctoral Thesis, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2011. (In Hebrew)

Klein, Ahuva. 'Women's Wedding Songs from Ra'ada,' Yeda-Am, 1981, pp. 76-83 (In Hebrew)

Ratzabu, Yehuda, 'Wedding Customs among Yeminite Women,' Orologin 11 (1955), pp. 329-341 (In Hebrew)

Ratzaby, Yehuda, 'Wedding Songs from Ra'ada in Yemen,' Mahnaim Pag (1963), pp. 52-59 (In Hebrew)

Shai, Yael, 'Song and Dance among the Women of Haba'an,' Tehudah 15 (1996), pp 54-57 (In Hebrew)

Nahshon, Yehiel. Diokana shel bat teman (me’ot 18-19). Netanya: Association for the Fostering of Society and Culture, Documentation and Research, 2007. (In Hebrew)

Shay, Yael. The Traditional Women Songs in Habban and their role in the Wedding. Ph.D. diss. Bar-Ilan University, 1985. (In Hebrew)

Spector, Johanna. “Bridal Songs and Ceremonies from San’a.” In Studies in Biblical and Jewish Folklore, edited by R. Patai, F.L Utley. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1960, pp. 255-284.