[1]The triple blessing, or the Priestly Blessing, is arguably the most impressive text within the Synagogue tradition.

Sources of the Priestly Blessing- the Holy Temple and the Early Synagogue

The Priestly Blessing, recited by the priests (Kohanim), the descendants of Aaron the high priest, was created when the Children of Israel were in the desert, and was developed in the Holy Temple of Jerusalem, where, during the ceremonies over the sacrifices, the priests gave daily blessings to the people. The commandment for the priests to bless the people and the formula of the blessing can be found in the book of Numbers 6:22-27:

The LORD said to Moses, 23 “Tell Aaron and his sons, ‘This is how you are to bless the Israelites. Say to them:

24 “‘“The LORD bless you

and keep you;

25 the LORD make his face shine on you

and be gracious to you;

26 the LORD turn his face toward you

and give you peace.”’

27 “So they will put my name on the Israelites, and I will bless them.”[2]

The priestly blessing is an ancient prayer that is both beautiful and classically simple. The blessing both requests and promises God's blessing, light and happiness, graciousness, and peace. The rhetorical strength to this prayer is found in its succinct form.

The prayer is no more than 15 words long and is organized through three sophisticated units.

- In each line God's name appears as the second word.

- In the second and third lines there are three common words (Adonay, Panav, Elekha [my lord, his face, towards you]).

- The length of the lines grows from three words to five and seven.

The structure of the lines and their rhythmic meter certainly played an important role in the fact that the Priestly Blessing has acquired much respect from ancient times up until the present day. Many have attributed the prayer with spiritual interpretations and have used it as a talisman to help guard against spirits and harmful things.

The biblical commandment of the Priestly Blessing does not provide the priests with any specifications as to when and how they are supposed to bless the Children of Israel. It is usually assumed that in biblical times, the blessings were performed during the daily sacrificial ceremonies. However, it was also recited by the priests during other occasions, especially during festive ceremonies that were of national importance.

The blessing was recited during a short prayer that the priests recited during the sacrificial ceremonies. This prayer included three blessings, Avoda, Hodaa, Shalom (the right to work the lord, a general thanksgiving, and a prayer for peace). The Priestly Blessing was recited in between the second and third blessing of this prayer. Thus, the prayer for peace could follow the promise for peace that is announced in the Priestly Blessing.

The priests performed the blessing while standing on the Dukhan, a raised stage, or on a step that leads from the main courtyard of the Temple to the wall that encircles the hall. The priests would stand face to face with the people and would lift their hands over their heads. They would then recite out loud the three lines of the blessing, without interruption, and then recite the Lord's name.

The Priestly Blessing went through a few changes in the transition from the Holy Temple to the early synagogue. In the synagogue, the priests raise their hands only to the height of their shoulders, and absolutely not over their heads; additionally, they pause after each of the three lines in order for the congregation to answer Amen; they also recite the Lord's name only as lordship and not his full name (Adonay rather than Yahweh).

The Development of the Practice within the Orthodox Movement

In the Orthodox movement, the ritual developed based on that of the early synagogue, which was, in turn, based on that of the Holy Temple. Throughout the centuries, many rules and interpretations were added to the blessing. In Rabbi Moses Isserles's (also known as the Rema 1525-1572) essay on the Shulhan Arukh, he summarized the Halakhot that were customary for the Ashkenazi Jews in that period. His version would become the template of practice for all of the Jews of Ashkenaz.

There are different traditions regarding when the blessing is to be recited: in Israel, and especially in Jerusalem, the ceremony is held on every day of the week during the morning prayers (Shaharit). It is held twice on the Sabbath, on the first day of every month (Rosh Hodesh), on the Three Pilgrimage Festivities (Pesah, Shavuot, and Sukkot), on Rosh Hashana, and on the four days of fast, and thrice on Yom Kippur. All of the Jewish communities in Israel, both Sephardic and Ashkenazi, follow this tradition.

In the Diaspora, it is a bit more complicated and the days in which the Priestly Blessing is recited changes from place to place.

The western Sephardic communities limited the blessing to the Sabbath, holidays, and the High Holy Days. The central European Ashkenazim limited it to the Three Pilgrimage Festivities and the High Holy Days. The Eastern European communities took the limitations the furthest and gave the Priestly Blessing a place only in the Mussaf of the Three Pilgrimage Festivities, and Rosh Hashana, and the Mussaf and Ne'ila of Yom Kippur.

There are a wide variety of reasons that caused these limitations. Possibly, the main reason was (although it cannot be proven) the fear that the constant repetition of this ceremony will permanently replace the Holy Temple with the Synagogue.

The Priestly Blessing in the Ashkenazi Tradition

While all of the Jewish communities, from Yemen to Lithuania, developed unique melodies for the blessing, the Ashkenazi community had the richest assortment of melodies, compositions, and pieces written for the Priestly Blessing. Paradoxically, it was, at least in part, because the Ashkenazi Diaspora communities performed the ceremony less than all of the other Jewish communities. In the Ashkenazi communities of the Diaspora, the ceremony could only be held during prayers that clearly express a pining to return to work in the Holy Temple in Zion. The fact that the Priestly Blessing was only performed on holidays and High Holy Days made it unique and granted it with a holy and mysterious aura, inspiring the Ashkenazi communities to glorify it with unique melodies and singing.

The Position of the Priestly Blessing in the Ashkenazi Synagogues

The common procedure of the Priestly Blessing in the Ashkenazi Synagogues is as follows:

During the leader of the service's repetition (Hazarat Hashatz) of the Amida prayer, when the cantor finishes the prayer of sanctifying the Lord, the priests leave their usual spot in the synagogue, remove their shoes, and go to the sink that is usually situated in the hallway; there, the Levites pour water over the priests' hands. After their hands are washed and dried, the priests return to the synagogue and when the cantor recites the blessing of work (Birkat Ha'Avoda), the priests approach the ark. If the synagogue has a Dukhan (raised stage before the ark), they go onto that, if not, they stand on the floor before the ark.

They face the ark as the cantor recites the prayer for work and thanks. When the cantor reaches the end of the prayer of thanks, to the words 'Vekol hahaim yodukha sela', the priests raise their Talits over their heads and pull them forwards so that their hands are covered. While they are doing this they recite the prayer, 'Yehi ratzon milfanekha, Adonay eloheinu ve'elohei avoteinu, shetehieh habrakha hazot shetzivitanu levarekh et a'mkha yisrael brakha shlema, velo yehieh bah shum mikhshol veaven me'ata ve'ad 'olam.'

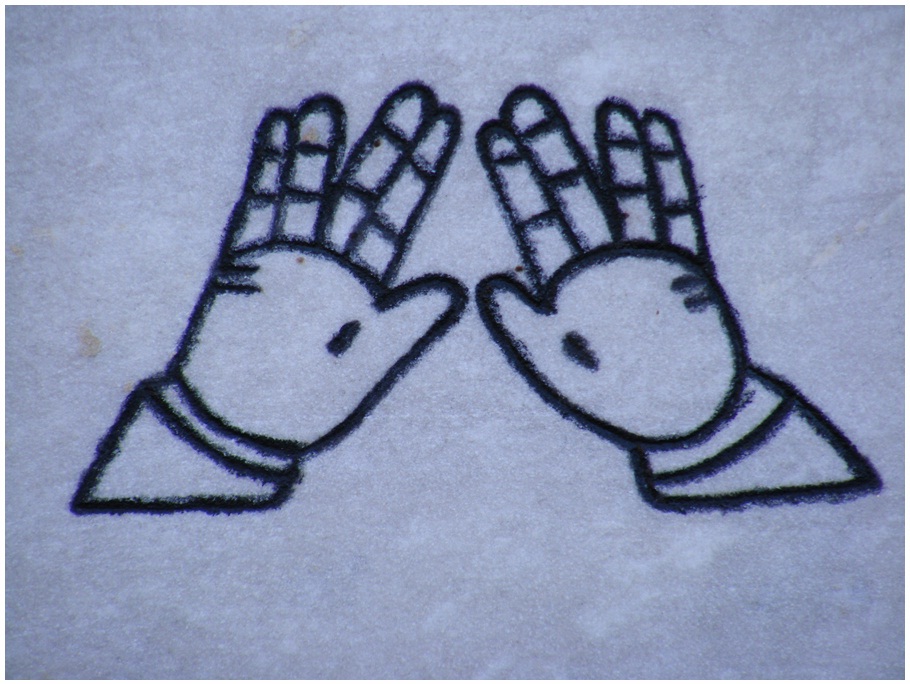

Afterwards, while still covered by the Talit, the priests raise their hands up to their shoulders with their fingers closed. When the cantor finishes the blessing of thanks, he, or another member of the congregation calls, 'Kohanim!' (priests!). This is the sign given to the priests to commence with the blessing, and for the rest of the congregation to come up and gather around them, but without looking at them. The congregation gathers, and all of those present in the synagogue lower their heads. In the meantime, the priests separate their fingers to the traditional figure in which each of their hands makes the shape of the Hebrew letter Shin (ש) , and bring their hands together so that thumb touches thumb. It is at this point that they begin reciting the blessing: 'Barukh ata adonay, eloheinu melekh ha'olam, asher kidashnu bkdushato shel Aharon…' (Our God,King of the Universe, Who sanctified us, with the holiness of Aaron). The priests now turn, clockwise, so that they are facing the congregation (up until now they were facing the ark). They finish the opening blessing with the words 'vetzivanu levarekh et amo Yisrael beahava' (and commanded us to bless His people Israel with love), to which the audience replies 'Amen.'

The cantor, or a member of the congregation, reads the words of the Priestly Blessing and the priests repeat them. While reading each of these seven words: Yevarekhekha, VeYishmarekha, Eleikha, VeYekhunakha, Eleikha, Lekha, and Shalom, the priests turn their hands that are covered by the Talit, to and fro, left and right (from north to south) in order to include the entire congregation in their blessing. The movement is lengthened with the last word, Shalom (peace). The congregation answers Amen after each of the three lines of the blessing.

After finishing the blessing, the priests turn around clockwise so that they again face the ark. They then lower their hands, close their fingers, return their Talit to its regular position, and whisper the following prayer, 'Ribono shel olam, a'sinu me shegazarta a'leinu, af ata aseh I'manu kema shehithtanu. Hashkifa mema'on kodshekha min hashamayim ubarekh et a'mkha Yisrael ve'et ha'adamah asher natata lanu, ka'asher nishba'ta la'avoteinu eretz zavat halav udevash' (Master of the universe, we have done that which you decreed upon us. You too, do unto us: 'Look down from your holy abode, from heaven ,and bless your people Israel and the land you have given unto us, as You had sworn to our forefathers a land flowing with milk and honey.').

Simultaneously, the cantor reads out loud the last blessing of the Amida in accordance to the modal character of that specific day. This is while the congregation reads to itself the Talmudic prayer: 'Adir bamerom shokhen bagevura, ata shalom ushimkha shalom yehi ratzon shetasim a'leinu ve'al 'amkha beit Yisrael haim ubrakha lemishmeret shalom' (Mighty [God] on High, who dwells by power. You are Peace and your name is Peace. May it be your will that you grant unto us and unto your people, the house of Israel, life and blessing to safeguard peace). The priests remain before the ark until the end of the repetition of the leader of the service. Afterwards, they descend from the stage, put their shoes back on, and return to their usual place in the synagogue. When they have returned to their place, the congregation blesses them, shakes their hand, and thanks them with the words 'Yishar koah.'

The Simple Reading

The musical capabilities of the priests are very diverse and change depending on the priest. Some of the priests have received no musical training. In fact, many were not even trained to recite the blessing, but rather, absorbed its melody from childhood, when listening to their father or another adult from their family. Each priest develops his own style, or different styles according to the existing melodies of his tradition. Therefore, when a few priests are reciting the blessing together, the result is heterophonic, that is to say, there is not complete unity between them.

Despite their lack of practice, many priests can chant very complex melodies. Therefore, when looking at the repertoire of the Priestly Blessings of the Ashkenazi synagogue from east to west, one finds that the melodies may range from simple recitation to complex melodies.

As shown above, the reading of the blessing is comprised of two parts:

- The precursory blessing to the Priestly Blessing is recited only by the priests: 'Asher Kidshanu bekdushato shel Aharon…' (who sanctified us with the holiness of Aaron).

- The Priestly Blessing itself is recited and every word is said by the cantor and then repeated by the priests.

The congregation answers Amen to the precursory blessing and after each line of the Priestly Blessing.

The Response Verses

In the Holy Temple, and possibly in the early synagogue, the congregation would remain silent during the recitation of the Priestly Blessing. Only a short response at the end of the blessing or at the end of each line was permitted. However, in the time that passed since this early period, people felt the need to offer prayers during this ritual, supposedly in order to give response to the blessings offered by the priests. A number of rabbis claimed that one must recite fifteen verses from the bible, each one during or immediately after each word of the Priestly Blessing. Others objected to this approach and only permitted the saying of Amen after each line of the Priestly Blessing. This debate originated during the Talmudic era and continues into the present day.

Bearing that in mind, and despite the rabbis' reservations, the response verses remained popular, although the variety of responses is diverse and changes from one community to the next. Throughout the centuries, the responses have become canonized and many Ashkenazi prayer books included the response verses. But even when the response verses were approved and even encouraged, they were not to be sung or said out loud, but rather whispered or recited silently. Nevertheless, there were communities that recited these verses out loud. In the late nineteenth century, in Lithuanian and Latvian synagogues, they were even sung as chorales. At the end of every line of the Priestly Blessing, the choir and congregation sang the response verses out loud and in metered melodies. However, this ritual was probably unique to specific synagogues and was not common among the rest of the communities.

While the common Ashkenazi custom as it was documented in many of the musical sources of the 19th century, was to use a short melody for each word of the blessing, several rabbinical sources mention the fact that the priests would extend the melodies, and even use a different melody for each word, and sometimes more than one melody for a word.

The Musical Tradition of the Priestly Blessing

Early documentation

Uncommonly, an early documentation of the music of the Priestly Blessing exists. A Venetian manuscript dated from 1714/1715, located today at Hebrew union College in Cincinnati, contains four notations of melodies of the blessing. The notating of these melodies was made as part of a debate that occurred in Ferrara in 1706 about the way in which the priests sing the words of the blessing while the congregation recites the response verses.

Central and Western Europe

The Ashkenazis of Central Europe used to adorn every holiday with its own distinct melody, or at least melodic structure. These 'seasonal melodies' were taken from different sources. Some of them were borrowed from liturgical or para-liturgical Piyutim, others were adopted from secular Jewish songs, as well as from non-Jewish sources. Some of these melodies went through some changes and were included in the Priestly Blessing ceremony, and in that case, served as a connection between the Priestly Blessing and the specific date in which the ceremony was conducted.

Abraham Baer, whose transcriptions were described above, supplies, in his textbook for cantors, an array of four such melodies. Itzik Offenbach wrote a similar set of five melodies, in his textbook for cantors.

Eastern Europe

In Abraham Baer's Siddur, there are examples of the Priestly Blessing from both Germany and Poland. The difference between the two traditions is quite obvious. While the Germanic synagogues use extended melodies for twelve of the words (excluding God's name which is sung with a short melodic motif), the melodies in the Polish tradition are mostly found on the seven words in which the priests move from left to right, and on the rest of the words, the melodies are shorter and simpler.

In contrast with their western brethren, the Eastern European Jews did not use seasonal melodies for the Priestly Blessing. A few synagogues in Eastern Europe used the Metim Niggun[3] for all of the holidays and High Holy Days, although, in most communities, other melodies were sung. The priests tended to prefer local melodies that were learned from a family member or someone from their town or village. When compared, textbooks from Germany and Eastern Europe show that in addition to differences in style and modality, there is a difference in the sources of the melodies. With a few exceptions, the German melodies appeared to come from the cantorial world of the traditional recitations, seasonal melodies (in accordance to the time of year), rococo music, and even a cantorial Fantasia. On the other hand, the Eastern European music's source is from folkloric inventions of the priests. In similarity with folk songs in general, while some were uniquely beautiful with interesting structures, others were nothing more than hackneyed songs.

Thanks to the creativity of the Hassidim, the collection of eastern European melodies for the Priestly Blessing grew through the wide variety of Niggunim. Some were created by the Hassidic leaders themselves, known as Rebbes (LINK: ADMOR). An exceptional example is the melody for the blessing of the Habad Hassidim, which was composed by the Kfa'lieh of the middle Rebbe (Rebbe Dov Ba'ar of Lubavic- 1774-1828), and was later printed in the first printed book of Habbad Niggunim, Niheh, printed by Zalmanov.

The Priestly Blessing and Dreams

The Priestly Blessing has been known to protect one from unclear dreams. In the Talmud, in Masekhet Brakhot, page 55:b, a passage appears that offers every person who had a dream at night, but does not know what it meant, to stand up when the priests extend their hands for the blessing, and to say certain phrases (which are cited in the Talmud passage) during the blessing. The person is supposed to say this prayer so that he will finish together with the priests; that way, when the congregation will say Amen at the blessing's conclusion, they will in fact be saying Amen for the prayer of the dreamer as well.

19th Century Changes

Along with the emancipation of the Jews of France and Germany, and the Jews' attempts to integrate with European culture during that period, awareness arose pertaining to certain flaws that appeared during the ceremonies in the synagogues with respect to etiquette. One of the most pronounced areas was the Priestly Blessing.

The aspects of the blessing's ceremony that were most bothersome were: the taking off the shoes in the synagogue; the excess emotions of the holiness while the priests went to the hallway and approached the ark; the congregants who would get up from their seats to congratulate the priests when they returned from the ceremony; the recitation read aloud by the cantor, or the congregants, in regard to dreams; the kabbalistc prayer recited at the end of the blessing; the unmusical chanting of the priests who were not necessarily musically inclined, and the hetero-phonic dissonances that appeared, even with those who could sing correctly.

A few of these concerns appeared in the new regulations that appeared in the new German synagogues (starting from the 1830s) and they were similar to those that were common in the communal ceremonies of the synagogues in the United States.

The reform movement eventually cancelled the Priestly Blessing. This was derived from both their aforementioned will to integrate with German society, and the fact that the blessing portrays a hierarchic outlook which prefers a certain group within the congregation, the priests. This outlook was in contrast to the egalitarian ideals that the Reform movement is based on.

Despite this, there remained a few Reform synagogues that mentioned the ritual regardless of the emotional and ideological reservations of the movement. The blessing was even performed at the Reform movement's flagship, the Hamburg Temple, but it gradually disappeared. In addition to the reasons mentioned above, another reason for the disappearance of the Priestly Blessing from the Reform movement was the movement's cancellation of the Mussaf for the Sabbath and High Holy Days. Since, in the Diaspora, the blessing was most commonly performed during these services, when they disappeared, so did the Priestly Blessing along with them.

The Priestly Blessing in the Reform Movement Today

The Reform movement in the United States' current trend is what can be termed 'spirituality.' In their search for spirituality, young Reform rabbis and communities search for means to research the world of emotions and beyond it.

Some of them were influenced by various eastern, non-Jewish sources, some researched ideas and rituals from the Kabbalah and neo-Hassidism, and some have tried to find spiritual ideas from the standard prayers. Under these circumstances, the Priestly Blessing was discovered as a source of inspiration. Ideas of tradition, law, liturgy, and without a doubt, a naïve outlook on Judaism, all melded together to create a new style of the Priestly Blessing. In Conservative synagogues, earlier attempts to revive the ceremony appeared, and in a few of them, the revival came alongside different innovations.

The association of the blessing with spirituality connects it with care and healing. Up until the year 2002,[4] there were a few different kinds and techniques for caring and healing. The Reform rabbis, influenced by American healers, attempted to use the Priestly Blessing for medical purposes, but there has yet to be any music composed for this.

[1] This entry is based on the article: Schleifer, Eliyahu. 'The priestly blessing in the Ashkenazi synagogue : ritual and chant.' Yuval 7. ed. Seroussi, Edwin and Schleifer, Eliyahu. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2002.

[3] A title to a melody that was used to memorial services, and in northern Germany was used to the Matnat Yad ceremony.

[4] The year the article The priestly blessing in the Ashkenazi synagogue : ritual and chant by Eliahy Schleifer was published, on which the term is based on.