The Sephardic copla, El incendio de Saloniki (The Fire of Saloniki), also known as La cantiga del fuego (The Song of the Fire) and, after its opening line, Día de Shabbat la tadre (On the Shabbat day, in the afternoon), was written in the aftermath of the Great Fire of Saloniki, which occurred on August 18, 1917. Especially destructive in scale, the fire came as a great blow to the Jewish community living in Saloniki at the time. The fire left tens of thousands of Jews homeless and consumed most of the Jewish neighborhood in the old city, including areas of commerce, libraries, schools, as well as over thirty synagogues, including the Chief Rabbinate.1

Map displaying the extent of the fire, with affected areas shown in black.

Though the destruction of the fire and its impact on the Jewish community would eventually be eclipsed by that of the Holocaust, the fire played a catalytic role in ending an era of Jewish life in Saloniki. Greek authorities viewed the fire’s devastation as an opportunity to rebuild the city according to Greek interests. Rather than returning the damaged property to its former owners, properties were auctioned off to those who could afford to pay. As a result, “The National Bank of Greece outbid the Jewish community for the plot on which the Talmud Torah, the main Jewish communal school, had stood before the fire. Today, the upscale Electra Palace hotel sits in the heart of the city where another Jewish school, the Alliance Israélite Universelle, once stood.”2

Despite a strong resurgence of activity among the Jewish community to re-establish itself after the fire, these efforts were ultimately negated by the Nazi occupation of Greece in WWII and the subsequent deportation of the Saloniki Jewish community to the death camps.

Jewish Saloniki: A Brief Survey

The Jewish history in Saloniki is essentially comprised of a few hundred vital years of cultural life, tragically bookended by the expulsion from Spain (1492) and the death-camps of the Nazis (1943). For over four-hundred years leading up to the Great Fire, Saloniki stood as a major hub of Jewish cultural activity. Though some Jews had lived in Thessaloniki (the current Greek name of the city) since Antiquity (see the New Testament letters of Paul to the Thessalonians), the great majority of Jews arrived to the city between 1492-97 after their expulsion from the Iberian peninsula. The Ottoman Empire largely absorbed these Jewish populations and Saloniki, under Ottoman rule since 1430, became one of their primary destinations.

With this large population influx, Saloniki was transformed into a multicultural city and commercial hub with a Jewish majority, often referred to as the “Balkan Jerusalem,” as even the main port and commercial centers closed on the Sabbath.3 In addition to the large Jewish population, the city was home to a great number of Turks and Greeks. According to the newspaper Yeni Asir, the Jewish population of Saloniki in 1906 was 47,312. Additionally, there were 31,000 Turks, 15,012 Greeks, 3,697 Bulgarians and 1,839 inhabitants of different origins.4 Therefore Saloniki, around the time of the Great Fire, was a “multicultural city, full of Jews, Greeks, and Muslims, each developing their own cultural traditions and speaking in their own languages.”5

The Jews that were expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492 carried their Judeo-Spanish culture with them as they migrated, including literary traditions, musical forms and the Judeo-Spanish language, Ladino. The Jewish musical life that developed in Saloniki consisted of these forms and, similar to many other Sephardic traditions in the greater Mediterranean and Middle-Eastern world, became blended to a degree with local cultural influences.

The Copla

Il Incendio de Saloniki is considered to be one of a number of twentieth-century coplas, a form that offers poetic commentary on historical events and Jewish festivities of the yearly cycle. Susana Weich-Shahak defines the copla as a poem that is generally strophic in form, with a varying but definite textual structure. According to Weich-Shahak, the majority of coplas were composed in the 17th and 18th centuries, and many were published in cities such as Saloniki, Istanbul, and Livorno.6 Through the copla, poetic commentary arises in the Judeo-Spanish language regarding life events experienced as a community, such as the festival of Purim, or in this instance, the Great Fire of 1917 in Saloniki. It is fair to note that the song “El Incendio de Saloniki” also serves a similar functional role to the medieval romances noticieros (informative, narrative songs), due to its recounting of historical events.7

Textual Content

Though many stanzas of this song exist, with different versions adding and omitting stanzas, most outline the movement of the fire through the city of Saloniki and the experiences of the displaced residents, concluding with a didactic message that attributes the cause of the fire to the the sins of not observing Shabbat (los pecados de sabat) and to God’s resulting anger and justice (theodicy). A passage by Weich-Shahak contextualizes portions of the lyrics within a summary of the fire:

“The fire started in a quarter named Agua Mueva and expanded through the city until the White Tower (Beyas Kule). Almost four thousand Jews, poor and rich (tanta probes como ricos) whose houses and possessions had been burned had to be evacuated. The Allies’ General Command Headquarters brought them to the barracks of Dudular, nine kilometers from the city. There they were housed in six hundred tents, where the British Allies gave them food (un pan amargo = a bitter bread) and shelter, (chadires ke el are los bolo = tents that flew away with the wind). As is customary in the coplas repertoire, this song has a didactic message stressing that this fire was punishment for the sins of not keeping the religious laws of Shabbat (los pekados del shabbat).”8

El Incendio de Saloniki lyric example with English translation

|

Dia de shabbat, la tadre, la horica dando dos, fuego salió al Agua Mueva, a la Torre Blanca quedó. Tanto probes como ricos, todos semos un igual. Ya quedimos arrastrando por campos y por kishlas. Mos dieron unos tsadires, que del aire se volan. Mos dieron un pan amargo, ni con agua no se va. Las palombas van volando haciendo estrución. Ya quedimos arrastrando sin tener abrigación. Entendiendo, mancevicos: los pecados de shabbat se ensañó el patrón del mundo, mos mando a Dudular. Dio del cielo, dio del cielo, no topates que hacer. Mos dejates arrastrando, ni camisa para meter. Mos estamos sicleando mos vamos onde el inglés por tres grushicos al día y un pan para comer. |

Day of Shabbat, in the afternoon, when the clock struck two, a fire broke out at New Water, and spread to the White Tower. Poor and rich alike, we became all equal. We remained in misery, in fields and barracks. They gave us some tents which blow away in the wind, We were given bitter bread which even with water wouldn't go down. The pigeons were flying spreading destruction. We remained in misery, without any shelter. Understand, young people: the sins on Shabbat incensed the Lord of the world, Who sent us to Dudular. God of the heavens, heavenly God, You could not find nothing else to do to us? You have left us destitute without a shirt to wear. With great grief we go to the English for work for three cents a day and for a loaf of bread to eat. |

Ladino text and English provided by Professor Edwin Seroussi, based on a recording by Greek artist Savina Yannatou.

Form

The textual form is built of a succession of stanzas, each consisting of 4 lines. The stanzas follow a loose rhyme scheme built upon common vowel sounds, creating an ABAB rhyme structure. Lines 1 and 3 share a common vowel sound, and in turn, lines 2 and 4 rhyme according to another common vowel sound, which is often different than that of lines 1 and 3. Additionally, lines 1 and 3 usually consist of 8 syllables total, whereas lines 2 and 4 consist largely of 7 syllables. The outline of the form can be visualized below:

A - 8

B - 7

A - 8

B - 7

The musical form is similarly strophic, with two separate musical phrases: A and B. Lines 1 and 2 of each stanza constitute A, whereas the concluding lines 3 and 4 create B. In many recorded performances of the song, the B portion is repeated, creating a musical form of ABB.

Melodic Outline

The overall melodic structure, primarily in minor mode, consists of an initial upward arc, which then descends, in conclusion, to its lowest point at the tonic note. Part A of each stanza quickly opens to the dominant, ascending upward to the 7th (minor) or octave scale degree (depending on the version) and concluding on the sub-dominant. In contrast, part B meanders its way, sometimes through a series of melismas, down to the tonal center.

Analysis of Performances

There are a number of commercial recordings of El incendio de Saloniki that have been produced in the past twenty to twenty-five years. There are also a number of ethnographic recordings of the song available, including quite a few at the National Library of Israel (NLI).

Below are a several versions of the song. Some are ethnographic recordings found at the NLI, while others are commercial recordings.

To start, here is an ethnographic recording from 1980 titled “Día de Sabbat la tadre,” sung by Rachel Vakil, which follows an AB form, possibly due to the nature of the recording as an ethnographic one.

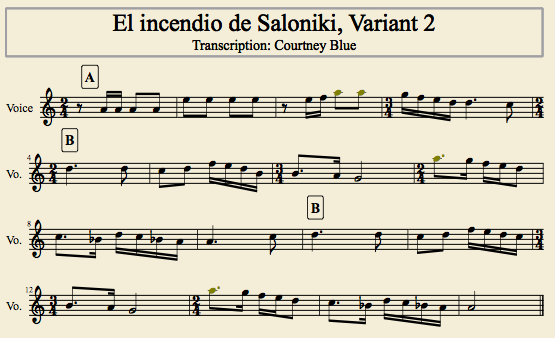

Sung to a similar melody to that of the recording above, below is a recorded performance from 1992 in Madrid, found at the NLI, which includes instrumental accompaniment. The song is also listed as, “Dia de sabbat la tadre,” performed by artists Blasco Sánchez and Adela Rubin. Here we see a fairly simple melodic outline, syllabic in nature, ascending and descending in stepwise motion, with a minor modality, as observed below in transcription form (variant 1).

Here we can also note that in this specific melodic structure, the A and B portions are not of equal length. A consists of 4 measures, whereas B consists of 6 measures.

Savina Yannatou, Primavera en Saloniko

The above version from Madrid is very closely related to the version below, “La Cantiga del Fuego,” from Savina Yannatou’s 1995 commercial album with Primavera en Saloniko. This performance shares a long instrumental introduction with the previous recording, and a similar melodic framework to the two prior recordings. Here Yannatou includes subtle ornamental figures to connect between notes of the overall syllabic, primarily stepwise melodic framework we have seen so far.

Yannatou approaches this album not as a strictly Ladino singer but rather as an institutionally trained Greek vocal artist that experiments with a wide range of vocal styles. The liner notes to this album reference the importance of Greeks acknowledging the ways in which Sephardic musical cultures shaped and interacted with daily life in Saloniki even fifty years prior, “in the poor neighborhoods, in the wealthy villas, and in the marketplace of [the] city.”9 Yannatou’s version, although relatively true to the other versions of the song we have listened to so far, is also indicative of a change in the role of Ladino music over the past century, from a living practice centered around Sephardic community life to a tradition in need of preservation, now valued as an historical object or as a commercial genre.

David Saltiel

Below are two recordings of David Saltiel, Sephardic community leader and cantor born in Saloniki in 1931. Saltiel offers us the voice of a singer at the center of the community where this music has been transmitted.

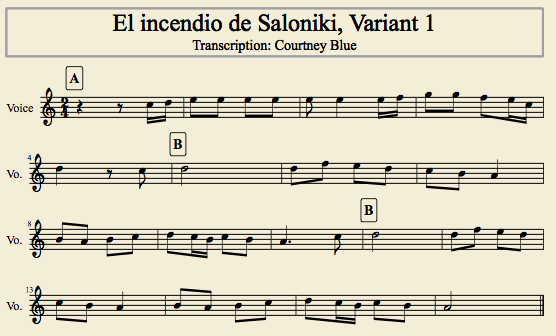

The first version by Saltiel is a brief ethnographic recording of the song, again titled “Día de Sabbat la tadre,” dated 1995. This recording, in contrast to three previous versions mentioned above (variant 1), displays a wider variety of ornamental activity, including more melodic leaps. Additionally, this version displays a level of rhythmic freedom not observed in the other recordings, including frequent pauses between phrases. Finally, possibly due to the nature of the recording as an ethnographic one, Saltiel does not repeat the B figure, instead singing an AB structure.

Below is a commercial recording of Saltiel singing “El Incendio de Salonika,” from 1998. Here he sings similar melodic figures to those from his ethnographic recording, with the addition of the backing of a full ensemble (oud, violin, lyre, qanun, frame drum) that echoes these melodies in instrumental interludes.

Though the overall melodic structure follows a similar outline to variant 1 above, there are a few points of difference, such as mm. 6-7 (see below: variant 2), which include a cadence on the 7th rather than the octave, followed by a large melodic leap, descending downwards. In contrast, the corresponding mm. 7-8 of variant 1 include a return to tonic, followed by stepwise motion upward and downward.

Unlike Saltiel’s ethnographic recording, here the metric form is clearly outlined, primarily performed in 2/4, with occasional groupings of the beat into 3. We can observe that this metric form differs from the first three examples (variant 1), which do not alternate between subdivisions of 2 and 3, but rather remain in 2. Below is an outline of metric form in Saltiel’s version that illustrates its connection to the melody. Measures consisting of two and three primary beats are grouped into sections, and placed below the section of the melody to which they correspond (from the melodic ABB form).

anacrusis (2)

A

2 - 2 - 3

B

2 - 2 - 3

2 - 2 - 2

B

2 - 2 - 3

2 - 2 - 2

B x 2 (Instrumental only)

(2) as pickup to A section, following same function as anacrusis

The A section consists of 7 beats (2 - 2 - 3), whereas B consists of 13 beats (2 - 2 - 3 / 2 - 2 - 2). The A section is almost half the size of the B section, different to the previous melody, whose ratio between A:B is 2:3.

This kind of metric scheme is common to Ottoman and Greek musical traditions, a testament to the mix of musical influences found in the Sephardic repertoire in general, and in Saloniki in particular. Another aspect which shows this complex relation is the lowered second scale degree in the descent to tonic at the end of verse B, which in Saltiel’s version provides a flavor of makam Bayati. The vocal melodies of the other versions, in contrast, remain in a Western minor modality.

The above sound examples provide two different melodic variants of the same song, interrelated with regards to thematic material and basic melodic structure, including shared cadential figures. They differ however with regards to meter, melodic ornamentation, and emphasized notes. Saltiel’s version includes increased traces of Ottoman and Greek influences due to the irregular metric structure and modality.

20th Century Ladino Songs and the Memory of Saloniki

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, the Ladino song tradition from Saloniki was transformed overnight into an item in need of preservation. Some new material has emerged, however, and in addition a number of artists keep this repertoire alive in performance. In 2013, one of the many wonderful versions of El Incendio de Saloniki was released as part of the album, Ventanas altas de Saloniki, a set of Ladino songs from Saloniki recorded by contemporary musicians Orit Perlman and Kobi Zarco, based on field recordings by Susana Weich-Shahak. The album includes a number of other 20th century songs from Saloniki, including a song addressing the subject of the Holocaust titled, La linda jovenica (La jovencita en el lager), a contemporary piece composed by Holocaust-survivor Moshe Aeliyon.

For further reading:

Elena Romero analyzes textual variants of El incendio de Saloniki in her book Entre dos o más fuegos, Fuentes poetics para la historia de los sefardíes de los balcanes. Madrid, CSIC, 2008, 661-665.

For a more in-depth discussion regarding Ladino song genres, including videos with song examples, see Susana Weich-Shahak’s entry in the NLI: http://web.nli.org.il/sites/NLI/English/music/Compilations/Pages/Judeo-Spanish_2.aspx

Article in the Times of Israel by Devin Naar recapping the Great Fire and its effects on the Sephardic community of Saloniki: https://www.timesofisrael.com/a-century-ago-jewish-salonica-burned/

Article in The Guardian recapping one hundred years of history in Saloniki since the Great Fire: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/aug/14/thessaloniki-spotlight-salonika-greece-refugees-great-fire

Another song regarding the Great Fire:

http://www.jewishfolksongs.com/he/el-dio-la-mate-esta-grega

Footnotes:

1. Albertos Nar, “Social Organisation and Activity of the Jewish Community in Thessaloniki,” in I.K. Hassitis, Queen of the Worthy, Thessaloniki, History and Culture, Volume I, 1997, pp.266-295.

2. Naar, Devin. “A Century Ago, Jewish Salonika Burned.” The Times of Israel. August 17, 2017. https://www.timesofisrael.com/a-century-ago-jewish-salonica-burned/

3. Hadar, Gila. Ventanas Altas de Saloniki. 2013. University of Haifa School of the Arts, the Department of Music. Liner Notes. p.13.

6. Weich-Shahak, Susana. Romancero, Coplas and Cancionero: Typology of the Judeo-Spanish Repertoire. Part 2. http://web.nli.org.il/sites/NLI/English/music/Compilations/Pages/Judeo-Spanish_2.aspx

7. Savina Yannatou, Primavera en Saloniko. 1995. Liner notes.

8. Weich-Shahak, Susana. Ventanas Altas de Saloniki. University of Haifa School of the Arts, the Department of Music. Liner notes, p. 40

9. Kokólis, X.A. Savina Yannatou and Primavera en Saloniko. 1995. Liner notes.