The Yiddish language, which probably began to develop around the tenth century A.D. in south Germany, was the main spoken language and language of oral creation of the Ashkenazi Jews of both Western and Eastern Europe, whereas in the latter region it was influenced by Slavic languages. Both the language and the folksongs, like many other elements of Ashkenazi culture, are made up of a combination of components from different cultures, geographical regions, and periods: the vocabulary, syntax, morphology, and prosody of Yiddish combine German and Hebrew components, and in Eastern Europe also elements of Slavic languages, as well as words of other surrounding languages. In a similar manner, the folksongs of the Ashkenazi Jews bare resemblance to Western European folksongs, Slavic songs from different periods, as well as Ashkenazi liturgical chants.

This combination of diverse and far ranging components is one of the prominent features of the Yiddish folksong. Throughout the ages it has been part of both rural and urban folklore and has developed oral traditions alongside an attachment to the written word. Its performance contexts include functional or gender specific performances (wedding songs, playsongs, lullabies, religious para-liturgical songs), as well as performances that are neither functional (lyric and narrative songs( nor gender specific )dance songs).

One of the earliest accounts of almost-contrasting elements, as a feature of the Ashkenazi folksong can be found in Sefer Hasidim, written by Rabbi Judah Ben Samuel of Regensburg (HaHasid) who died in Regensburg in 1217, paragraph 238 (רלח):

He who has a little son in a cradle, in order to prevent him from crying, should not sing him songs and melodies of the gentiles or Hebrew melodies that are meant for God. However, if there are rhymes from a passage from the Bible or Talmud that he sings in order not to forget them, even though the child is quiet and enjoying them, it is permitted.

This example is first and foremost an account of secular songs being sung in the local vernacular, as well as the adoption by the Jews of folksongs that surround them. However, it can also be seen as an example of the blurring of the boundaries between religious and secular songs, as well as the boundaries between oral and written forms of distribution. This blurring of boundaries was understood, and at parts, even condoned by the author: apparently, the putting to sleep of the baby, a secular activity, was sometimes accompanied by non-Jewish melodies, sometimes by religious melodies, and sometimes by study-tunes, and it was needed to be determined what the acceptable and 'kosher' alternative was.

As it seems, the repertoire mentioned by Judah HaHasid, of songs in mediaeval German and an assortment of religious songs, is very different from the traditional repertoire of Yiddish songs that was documented at the turn of the nineteenth century. However, the blurring of boundaries mentioned here can be seen as a precedent for a practice that would become one of the defining characteristics of this tradition.

Recognition of the tradition of Yiddish folksongs - which incorporate an affinity to the 'high' culture of canonical texts in Hebrew along with an affinity to oral folk culture - as well as seeing this tradition as opposed to the rabbinical culture, can be seen in the words of Maharil () (Rabbi Ya'akov Ben Moshe Levi Moelin c. 1365-1427) in Sefer Minhagim, Likutim, 59:

He said: rhymes and verses that are created in the Ashkenazi language, about the Unification [Yihud], and the thirteen principles of faith, it is better that they would not have been created. Because most of the common people think that these contain all of the Mitzvas, and they disregard other Mitzvas, prohibitions and permissions, like putting Tzitzit or Tefilin, Torah study, and more, and they think it is enough to say these rhymes with intention [Kavanah]. But these rhymes hardly imply the principles of the Jewish faith, and not even one of the 613 Mitzvas that the people of Israel are obliged to do.

Chone Szmeruk (1978) and other researchers saw these words as an evidence of the distribution of anonymous Yiddish songs in the fifteenth century. The wide circulation of these songs led, in the sixteenth century, to the incorporation of the folksong Almekhtiker Got in the Ashkenazi Passover Haggadah canon, as well as the special occasion prayer Got fun Avrom into the Ashkenazi Birkon (blessing booklet). Almekhtiker Got, which is a Yiddish version of the Piyut Adir Hu, as well as other Yiddish folksongs that have a similar serial structure, continued to be sung until recently. Serial songs constitute large parts of the repertoires of religious and secular folksongs (for example the songs Yidelekh vos shloft ir, eyns, tsvey, dray, fir; Zol ikh vern a rov, ken ikh nisht keyn toyre; Vos zhe vilstu, a shnayder far a man?).

Picture no.1: Almekhtiker Got, the Yiddish folk version of the Piyut Adir Hu, taken from the Prague Haggada, 1527. [Scanned books from the archive of the National Library of Israel]

Sound example no. 1: Got fun Avrom, a special occasion prayer – Tehina – for the end of the Sabbath, chanted by Bella Briks-Klein, recorded by Oren Roman 2007. The earliest known printed version of this prayer is from 1580 and is found in the Birkat Hamazon (Prague?, Mehlman Collection, The National Library of Israel). In the oral tradition, the Tehina can be found in different versions and was documented in many collections of folksongs, including Ginzburg-Marek (1901), and Pryłucki (1911). Both the melody and the words of the folk versions of this Piyut can be seen as a meeting point between the traditional Yiddish folksong and the Ashkenazi liturgy.

The openness of Yiddish folksongs to different cultural strata, makes it possible to speculate in regards to the musical development of the tradition, despite the lack of early documentation of the musical aspect. One might assume that several modes and structural patterns developed in the Yiddish folksongs in a similar way to their development in other Ashkenazi music repertoires which were documented, such as Klezmer melodies as well as liturgical and para-liturgical corpuses. The small amount of documentation done at the beginning of the twentieth century, exhibits similarities between the Yiddish folksong tradition and other types of Ashkenazi music. These can be found, for example, in the melodic lines, motif and rhythm formulas, and mode characteristics, that are documented in HaNoheg BeHasdo, a cantorial piece found in one of the earliest surviving manuscripts (1744), (Nadel manuscript, RISM 221, Adler 1989: 572), and which are common to many documented Yiddish folksongs melodies. Picture no.2: Hanoheg Behasdo:

The ambition for rhythmic variation, the pronounced fourth degree in the natural minor scale, and the motivic relationships based development of the musical form – as was documented in the Klezmer piece Old Jewish Dance from 1864 (Karpenko) in the following example – can also be found in many collections of Yiddish folksongs that were published in the twentieth century. Picture No.3:

Most of the documentation of the musical traditions of the Yiddish folksong was done during the first half of the twentieth century. From the outset, the process of collecting, transcribing, and preserving the melodies was done in an attempt to answer the question 'what is the Yiddish folksong?' Scholars still do not agree on the answer and when examining the early publications that document Yiddish folksongs (Including Golomb 1887, Grünwald 1898, Engel 1909-1912, Brounoff 1911, Kiselgof 1912, Cahan 1912, Kaufmann 1920) one is exposed to a wide variety of different repertoires. For example, one of the earliest collections that documents the eastern Ashkenazi folk tradition is Sammlung Jüdischer Lieder und Gesangstücke by H.E. Golomb (Vilna 1887), which contains six instrumental pieces, and six songs by the famous Badkhn Eliakum Zunser whose connections with the folksong tradition is only indirect.

Furthermore, during the second half of the nineteenth century, popular poems, written by well known poets were spread with the title of 'folksongs'. The phenomenon was criticized only about half a century later, in 1901, when Joel Engel, the Jewish composer and pioneering ethnomusicologist, responded to the collection titled Yudishe folkslieder (Jewish Folksongs) by Mark Warshawsky. Engel noted the distance between Warshawsky's songs and folk songs as well as the confusion that was caused by calling the songs that Warshawsky composed 'folksongs'.

In fact, the question of the Yiddish folksong's identity comes up from the earliest remaining documentation of this repertoire – the Wallich manuscript from the early seventeenth century (Butzer-Hüttenmeister-Treue 2005, Matut 2011). The manuscript contains 55 songs that were probably transcribed by Isaac Wallich (died in 1632, Worms). Most of them are German folksongs written with Hebrew letters, and twelve contain Jewish themes. The author of the manuscript called the songs 'folksongs.' The question whether the Jewish songs that Wallich collected were indeed rooted in a Jewish or German folk tradition, or conversely not attached to the folklore canon at all, is still asked today. Moshe Beregovski (1892-1961, Kiev), the greatest researcher of Ashkenazi folk music, ascertained that the main elements of the Yiddish folksongs’ tradition developed during the sixteenth century in Western Europe, and that remnants of them can in fact be found in Wallich's collection (Beregovski 1962).

Are there any remnants of this tradition left today? Only few songs constitute the repertoire that survived the vicissitudes of the modern era - the Enlightenment and emancipation, the disintegration of the traditional lifestyles, the urbanization and industrialization processes - and that was documented at the turn of the twentieth century, before the decline of Yiddish folk-singing due to the Holocaust, the mass emigrations, and the hostility towards Yiddish in Israel and in the Soviet Union. However, within this limited repertoire, a few shared musical characteristics can be found. These include: modality on which the monophonic songs are based, musical rhetorics that maintain a structure that differs from Western-European periodic structures, and asymmetrical rhythms. The dynamics between the text and music change from genre to genre. In the Hassidic songs, even when they have words, the music is dominant; in Yiddish dance songs the text and music are both equally important, while in Yiddish lyrical songs, and even more so in narrative songs, the words are the most dominant part. In these latter songs, the melody functions as an element that organizes the deliverance of the lyrics and designs the boundaries of the genre.

From the vast assortment of Yiddish folksongs types, two dominant patterns that demonstrate the traditional musical thinking will be presented: the melodies of the lyrical songs and the melodies of the serial songs.

Traditional Lyrical Songs

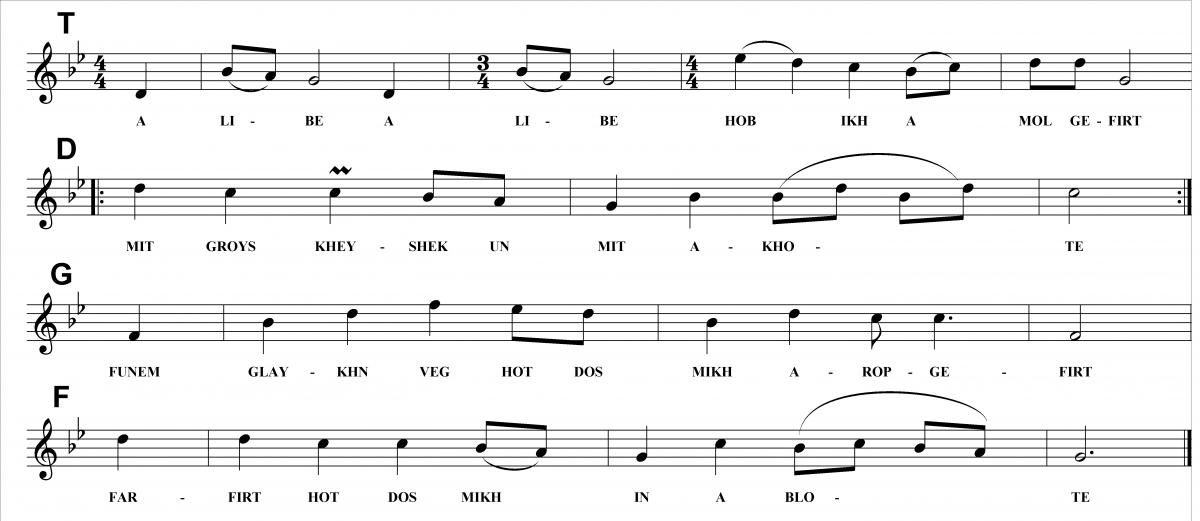

In these songs, the melody dictates the poetic structure, which includes the strophe length, lines division, poetic rhythm, and emphasizing the important parts while diminishing the less so. The traditional lyrical melodic structure will be demonstrated by the rare recording of the song A libe a libe sung by Julio Kaufman and recorded by his daughter Susana Weich-Shahak in 1975. Picture no.4, sound example no.2: A Libe a Libe, lyrical folksong:

|

אַ ליבע, אַ ליבע האָב איך אַ מאָל געפֿירט |: מיט גרויס חשק און מיט אַכאָטע, :| x2 פֿונעם גלײַכן וועג האָט דאָס מיך אַראָפּגעפֿירט, פֿאַרפֿירט האָט דאָס מיך אין אַ בלאָטע. |

אָט דאָס ט'מיך פֿאַרפֿירט, |:און כ'קאָן פֿון איר נישט אַרויסקריכן, :| x2 נאָר וויפֿל געלט זאָל מיך נישט אויפֿקאָסטן, נאָר פֿאָרן וועל איך אים אָפּזוכן! |

|: און אויב איך וועל אים ניט געפֿינען, :| x2

מיט אַ קליינטשיקן קינד אין מײַן בויך,

וואָרפֿן וועל איך מיך אין ברונעם

Additional versions: Skuditski Z., Folklor lider, v. II, Moscow, 1936, (p. 179 no. 37-38); Cahan, Y.L., Yidishe folkslider mit melodien, v. I, New York, 1912, (p. 202, no. 6); Yidishe folkslider fun Moshe Beregovski, St. Peterburg, 2007, (p. 58, 156, no. 11).

The Yiddish lyrical melody has a traditional four-part structure that combines four musical phrases that are organized in a hierarchal manner, with each phrase having its own musical function. The first phrase introduces a musical theme (Tonic), the next phrase develops it (Development), the third phrase heralds the closing of the strophe (Heraldic), and the final phrase enhances the closing feeling (Finalis).

The correspondence between the music and text is traditional as well: in most of these songs, each poetic verse corresponds with a musical phrase. Therefore, since the musical structure is clear and is not open to various interpretations, it dictates the poetical structure as a series of strophes with each containing four lines.

In addition to the clear structure and ways of correspondence between the words and music, the lyrical melodies also have clear modal characteristics. For example, the previously discussed song's melody is rooted in the natural minor mode which is similar to the traditional prayer nussach of Eastern Europe and is a mode in which the sub-tonic and the fourth degree are emphasized.

Finally, the traditional structure and the modal character of the songs are integrated with unique rhythmic structures that continuously elude rhythmic symmetry.

It can be concluded that the traditional lyrical pattern consists of a combination of traditional form, traditional manner of correspondence of text and music, Ashkenazi modality, and specific rhythms.

Traditional Serial Songs

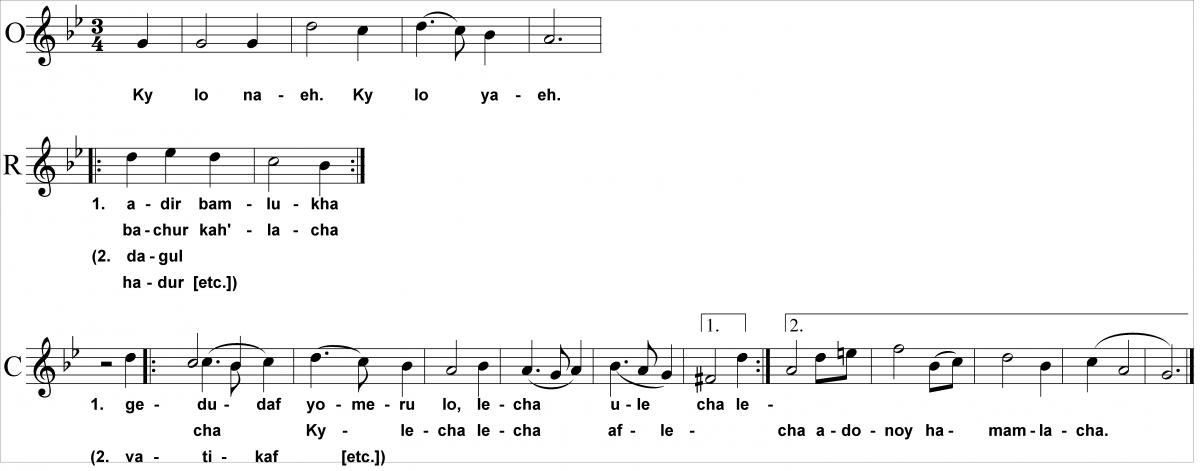

The earliest surviving documentation of an Ashkenazi serial song's melody from the Modern period is the melody to the Piyut Ki Lo Na'e from the Rittangel Haggadah (Königsberg, 1644). Picture no.5:

The serial melodies, like the traditional lyrical melodies, have unique musical rhetorics, although the serial structure differs from the lyrical one. The serial melodies are usually comprised of a recitative-like opening, which is occasionally based on the motifs that are traditionally used to learn canonical texts (Opening); a middle section, which is characterized by a repetition of a small number of motifs (Recitation); and a closing segment that has a dance-like character and usually occurs with a rhythmic and modal change (Conclusion). The three parts of the Yiddish serial structure are not equal in length and widely differ in their character as well as their musical function. The melody that is known today in Israel to the Piyut Ehad Mi Yode'a is anchored in this traditional structure.

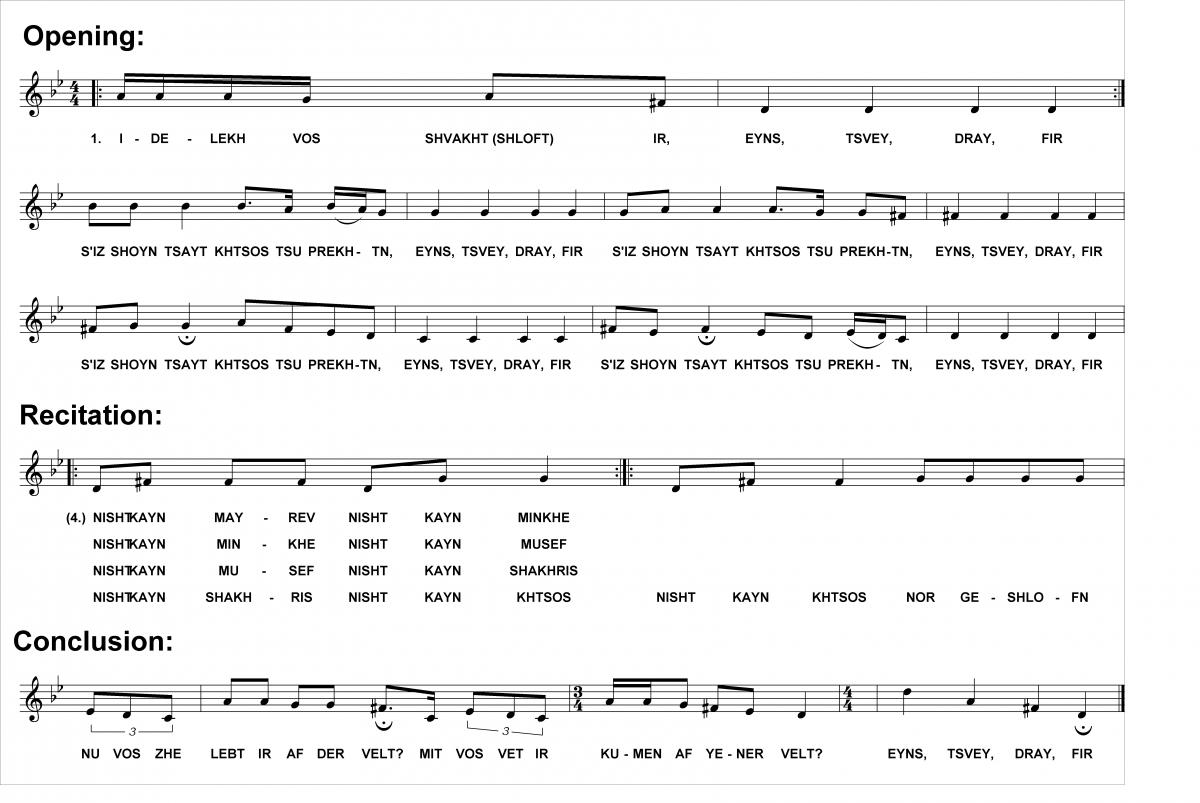

The serial song Yidelekh vos shloft ir, eyns, tsvey, dray, fir, as it was sung by Simha Rashkovski and recorded by Edith Gerson-Kiwi) in 1951, shows these elements of musical rhetoric. Sound example no.3, the serial song Yidelekh vos shloft ir, eyns, tsvey, dray, fir, picture no.6:

As was previously mentioned, along with the lyrical and serials songs, there were many more repertoires, including narrative songs, dance songs, Badkhonim songs, lullabies, play-songs, and religious songs. Every repertoire had its own musical and textual characteristics, function, and expression, and it is beyond the scope of this article to attempt and describe all of them.

Traditional musical patterns influenced many of the writers of Yiddish songs that were active in Eastern Europe and the United States during the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. Among them are Berl Broder (1815 Ukraine - 1868 Romania), Abraham Goldfaden) (1840 Starokonstantyniv [today in Ukraine]– 1908 New York), Salomon Shmulewitz (1868 Pinsk [today in Belarus] – 1943 New York), and Mordechai Gebirtig (1877 Krakow – 1942). The popular Yiddish songs that are well known today usually represent the heritage of these writers, and so, songs such as Goldfaden's Rozhinkes mit mandlen, Gebirtig's Hulyet, hulyet kinderlekh, and Shmulewitz's A brivele der mamen are erroneously referred to as folksongs.

The majority of researchers agree that the tradition of Yiddish songs faded away during the second half of the twentieth century, and that the small amount of documented songs left have not been thoroughly investigated. Therefore, one could say that what is known today in regards of the thousand year tradition of Ashkenazi folk music is only the tip of the iceberg.

In recent years, there have been important attempts to revive the Yiddish songs. Among them is the important work of the Mlotek family in New York and the song anthologies that they have published. Young Jewish and non-Jewish singers alike are performing the songs that were documented in print. What helped in this aspect was the growing demand for Klezmer music and the neo-Klezmer bands that appear all over the world. However, with these examples, the Yiddish song is no longer in its natural environment, but rather has become the object of concerts and recordings, that change its character in an attempt to preserve it for future generations.

Bibliography

Adler, I., Hebrew notated manuscript sources up to circa 1840: a descriptive and thematic catalogue with a checklist of printed sources, München, 1989.

Idelsohn, A.Z., Hebraeisch-orientalischer Melodienschatz, VIII-X, Leipzig, 1932.

Engel, J., Jüdische Volkslieder, Moskau, 1909-1912.

Butzer, E., Hüttenmeister, N., & Treue, W., 'Ich will euch sagen von einem bösen Stück... : ein jiddisches Lied über sexuelle Vergehen und deren Bestrafung aus dem frühen 17. Jahrhundert', Aschkenas, 15,1 (2005) 25-53.

Береговский, М., Еврейские народные песни, Москва, 1962. [Beregovskii, M, Evreiskie narodnie pesni, Moskva, 1962]

Golomb, H.E., Klaenge der Juden, Vilne, 1887.

Гинзбург, С. & Марек, П., Еврейскiя народныя пъсни въ Россiи, С.-Петербург, 1901. [Ginzburg, S. & Marek, P., Evreiskie narodnye pesni v Rossii, S.-Peterburg, 1901]

Grünwald, M. (ed.), Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für jüdischen Volkskunde, Hamburg, 1898-1929.

Matut, Diana, Dichtung und Musik im frühneuzeitlichen Aschkenas: Mss. opp. add. 4° 136 der Bodleian Library, Oxford (das so genannte Wallich-Manuskript) und Ms. hebr. oct. 219 der Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek, Frankfurt a. M, Leiden. 2011.

Mlotek, E., Mir trogn a gezang! Favorite Yiddish songs of our generation, New York, 1972.

Mlotek, E. & Mlotek, J., Pearls of Yiddish song, New York, 1988.

Mlotek, E. & Mlotek, J., Songs of generations, New York, 1996.

Kaufman, F.- M., Die schoensten Lieder der Ostjuden, Berlin, 1920.

Карпенко, С., Васильковский соловей Киевской Украины ... с присовокуплением малороссийских и еврейских танцев, С.-Петербург, 1864. [Karpenko, S., Vasilkovskii solovei Kievskoi Ukrainy, S.-Peterburg, 1864].

Mlotek, C. & Slobin, M. (eds.), Yiddish folksongs from the Ruth Rubin archive, Detroit, Mich., 2007.

Rosenberg, F., ‘Ueber eine Sammlung deutscher Volk- und Gesellschafts-Lieder in hebraeischen Lettern’, Zeitschrift fuer die Geschichte der Juden in Deutschland, (ed. L. Geiger), 1888-1889.

ענגעל, י', 'אַ תּשובֿה דעם הערן שלום-עליכם', דער יוד, 40, 1901.

מרגליות (ברודר), ב', שירי זמרה, למברג, 1865.

ברונאָף, פ', יודישע פאלקס ליעדער, ניו-יורק, 1911.

וואַרשאַווסקי, מ', יודישע פֿאָלקסליעדער מיט נאָטען, קייב?, 1900.

כּהן, י'ל, יודישע פֿאָלקסליעדער מיט מעלאדיען, ניו-יורק, 1912.

פּרילוצקי, נ', ייִדישע פֿאָלקסלידער, כרכים II-I, ורשה, 1911-1913.

קיסעלהאָף, ז', ליעדער זאַמעלבוך פֿאַר דער אידישער שול און פֿאַמיליע, פטרבורג, 1912.

קיפניס, מ', פֿאָלקס לידער מיט נאָטען, ורשה, 1918.

שמרוק, ח', ספרות יידיש – פרקים לתולדותיה, תל-אביב, 1978.

Selected Sources of Yiddish Folksong Music

Idelsohn, A.Z., Hebraeisch-orientalischer Melodienschatz, VIII-X, Leipzig, 1932.

Engel, J., Jüdische Volkslieder, Moskau, 1909-1912.

Береговский, М., Еврейские народные песни, Москва, 1962. [Beregovskii, M, Evreiskie narodnie pesni, Moskva, 1962]

Golomb, H.E., Klaenge der Juden, Vilne, 1887.

Grünwald, M. (ed.), Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für jüdischen Volkskunde, Hamburg, 1898-1929

Grözinger, E. & Hudak-Lazić, S., “Unser Rebbe, unser Stalin ...' : jiddische Lieder aus den St. Petersburger Sammlungen von Moishe Beregowski (1892-1961) und Sofia Magid (1892-1954). Wiesbaden, 2008

Mlotek, E., Mir trogn a gezang! Favorite Yiddish songs of our generation, New York, 1972

Mlotek, E. & Mlotek, J., Pearls of Yiddish song, New York, 1988

Mlotek, E. & Mlotek, J., Songs of generations, New York, 1996

Kaufman, F.- M., Die schoensten Lieder der Ostjuden, Berlin, 1920

Карпенко, С., Васильковский соловей Киевской Украины ... с присовокуплением малороссийских и еврейских танцев, С.-Петербург, 1864. [Karpenko, S., Vasilkovskii solovei Kievskoi Ukrainy, S.-Peterburg, 1864]

Mlotek, C. & Slobin, M. (eds.), Yiddish folksongs from the Ruth Rubin archive, Detroit, Mich., 2007

בערעגאָווסקי, מ', ייִדישער מוזיק-פֿאָלקלאָר, מוסקבה, 1934

ברונאָף, פ', יודישע פאלקס ליעדער, ניו-יורק, 1911

רוזשאַנסקי, ש' (רעד.), אבֿרהם גאָלדפֿאַדען: אויסגעקליבענע שריפֿטן, בואנוס-אירס, 1972

גורלי, מ', ביק, מ' (עורכים), די גאָלדענע פּאַווע, חיפה, 1970 – 1974

וואַרשאַווסקי, מ', יודישע פֿאָלקסליעדער מיט נאָטען, קייב?, 1900

רוזשאַנסקי, ש' (רעד.), מאַרק וואַרשאַווסקי: ייִדישע פֿאָלקסלידער, בואנוס-אירס, 1958

כּהן, י'ל (רעד.), ייִדישער פֿאָלקלאָר, פֿילאָלאָגישע שריפֿטן פֿון ייִוואָ , 5, וילנה, 1938

וויַינריַיך, א', (רעד.), כּהן, יהודה-לייב : ייִדישע פֿאָלקסלידער מיט מעלאָדיעס, ניו-יורק, 1957

לעהמאַן, ש', גנבֿים לידער : מיט מעלאָדיעס, ורשה, 1928

נוי, ד. & נוי, מ (עורכים), שירי-עם יהודיים מגאליציה, ירושלים, 1971

קיסעלהאָף, ז', ליעדער זאַמעלבוך פֿאַר דער אידישער שול און פֿאַמיליע, פטרבורג, 1912

קיפּניס, מ', 140 פֿאָלקסלידער, ורשה, 1930

שטערן, י', חדר און בית-מדרש, ניו-יורק, 1950

שאַכנאָווסקי, נ., לידער : געזונגען פֿונעם פֿאָלק, פריס, 1958